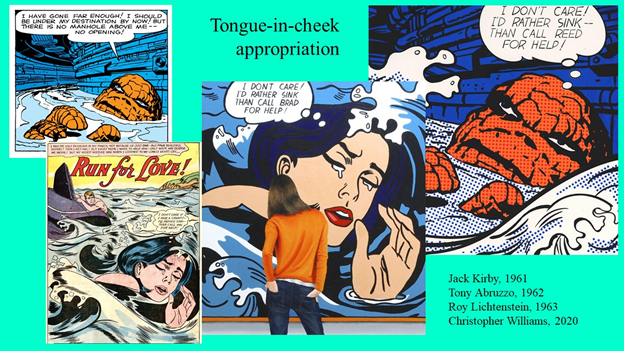

When teaching Mario Bava’s cult movie Danger: Diabolik! (1968) in a class this spring, I gave a little lecture on Pop Art, exploring affinities between the bright, playful appropriations of artists like Richard Hamilton, Andy Warhol, and Claes Oldenburg and such comic-strip-based films as Modesty Blaise (Joseph Losey, 1966), Barbarella (Roger Vadim, 1968), and Diabolik! During my talk, I flashed a PowerPoint slide that juxtaposed four images by four different artists.

Up to this point, my students had been silent, but this slide tweaked one to voice objections shared with generations of comics fans and art critics: “How is this Art with a capital-A? Lichtenstein ripped off the guy who drew that romance comic!” I improvised a half-hearted defense based on Pop Art’s ability to throw doubt on the traditional definition of capital-A Art, but nobody bought it. They were more intrigued when I mentioned that Christopher Williams, the artist who came up with “Drowning Thing,” was previously a student of mine who now works as a graphic novelist and poster maker.

I’m still uninterested in summoning up either a defense or critique of Pop and (post)modern Art, mostly because I find it all so absurd. When Banksy builds a frame that shreds a painting minutes after its auction at Sotheby’s, he’s reminding us that the essence of much contemporary High Art is a combination of Warholian self-reflexive commentary and the aesthetics of the prank. I find some pranks funnier than others—Banksy’s joke is pretty good—but I don’t turn to a museum or critic-sanctioned work for originality, spiritual guidance, or the frisson of the sublime. Comics have always given me more of a charge than museum art.

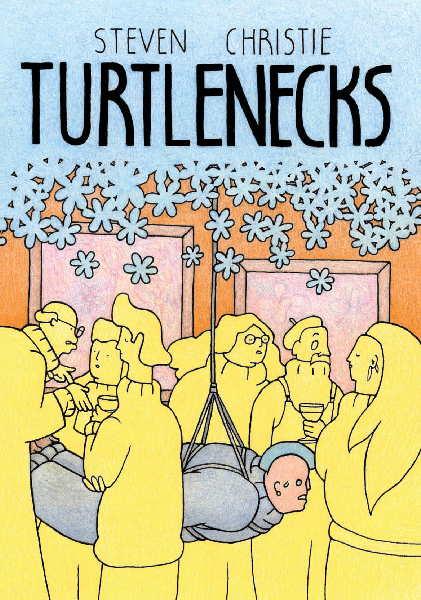

Blessedly, Steven Christie, in his new graphic novel Turtlenecks, gets the joke and finds it amusing. Here’s the premise: at an art school in the year 2035, student Sam ill-advisedly puts their favorite object—a “Readymade,” a big, blue, plastic flower they’d wear around their neck everywhere like Flava Flav wears his clock—up for sale at the school’s fine arts auction, only to lapse into immediate depression when the flower actually sells. The flower now belongs to Noah, a gallery owner who plans to display it in an upcoming exhibit of Sam’s work. But Sam wants it back now, Noah refuses, and Christie’s narrative spins out into a parody of heist movies, as Sam and a sympathetic group of art-world misfits scheme to steal the flower from Noah’s gallery before the exhibit opens.

Some of the charm in Turtlenecks comes from Christie’s gentle satire of art theory concepts. When Noah insists on keeping the flower, Sam angrily fires Ditkoesque energy out of their hands, designed to strip the readymade of “its status as an ART OBJECT!!” Then, on a page turn, we see Sam’s energy glance off the flower, as Sam’s friend Jules notes that the flower is “protected by some sort of aura!” This is a clever riff on the concept of the “aura”—defined as an artwork’s specific “presence in time and space” that cannot be duplicated by copies—in Walter Benjamin’s assigned-for-Art-majors essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936). Christie shows how the aura further contributes to the value of an art piece later in Turtlenecks when Noah offers to sell Sam’s flower to an art collector for $5000: “But for $6000 you get the sense of lose [sp.], concerns of materiality…and heck, I’ll even throw in the historical context for free. Y’know, connection to the decorative arts, still life…momento [sp.] mori. And for $7000 you can have all that including total rights to the work. That’s all configs, mods, ephems and interps.” Christie’s joke: all of this is “ephem,” meta-smoke and meta-mirrors, when we’re talking about a mass-produced plastic flower Readymade instead of a hand-crafted, unique object. (Just ask Marcel Duchamp.)

Turtlenecks shows us A Portrait of the Comics Artist as a Young Man: Christie is full of energy, exuberantly discovering what his art can do. His first book, Arrowheads [2019], features many of the same characters as Turtlenecks, and it’s entertaining to watch Christie’s narrative ambition grow even as his satire remains laser-focused on the art world. His people are minimally drawn, little lumps with tiny Orphan Annie eyes, but their postures and gestures nicely communicate their emotions; you can see what someone is thinking by how they hold their Stay-Puft hands or lean against a gallery wall. Christie also occasionally shifts into different mark-making, like in an early moment in the book where Sam’s despair over selling the flower is conveyed by a multi-panel collapse of referential shapes and forms into blobby abstraction. (The would-be culprits’ drive to the gallery likewise transforms from faint marks to wavy blobs to the arrival of the van over the course of a page.) And Christie’s colors—done with pencils?—are a soft, organic alternative to aggressive (and aggressively gradated) digital coloring.

I do have a few quibbles. The futuristic milieu seems superfluous, since the art world satirized in Turtlenecks is very similar to ours, except for unexplained touches like a crabby installation technician who is a human-sized, horned, blue lizard. Perhaps Turtlenecks’ satire would’ve felt even more effective if Christie had come up with art-world ideas that were ridiculous but nevertheless rooted in today’s trends and excesses. And the layouts in the book aren’t consistent: on several pages, including all the pages of “Wednesday,” the second chapter, Christie squeezes a lot of panels on each page. The lettering becomes smaller in these panels too. It’s almost as if Christie originally expected to publish Turtlenecks in a larger size and didn’t redraw these pages for the current paperback-size format. They stick out—distractingly, I think—from the rest of the book’s more decompressed pace and flow.

Nevertheless, Turtlenecks is a nice way for Christie to introduce his comics to American alt-comix readers, and yet another example of AdHouse’s commitment to new artists. Like everyone else, I was surprised and saddened by publisher Chris Pitzer’s announcement that he’ll be shutting down AdHouse after his next two projects, even while I remain grateful for Chris’ willingness to publish early books by such cartoonists as Josh Cotter, Sophie Goldstein, Max Huffman, Matt Lesniewski, Hartley Lin, and Christie. Chris’ talents as a book designer—and his harmonious collaborations with artists on these designs—led to unique books. Works of art, maybe?

Here’s the moment, at the end of my review, that I would normally enthusiastically recommend that you read Turtlenecks, but, alas, you won’t be able to find it. I’ve arranged with Pitzer to buy out the entire print run, and next month, SOLRAD will announce their Turtlenecks Bonfire, where we’ll burn all but a single copy of Christie’s book. We’ll then ship off that last copy (in mint condition) to the Certified Guaranty Company (CGC) in Florida, who will entomb it in a “protective holder” to maintain its aura. And five years hence, we’ll have a Turtlenecks “Dismemberment Party,” where we’ll crack open the plastic shell and cut the book into separate pages. Each ticket holder will get to keep one page of Turtlenecks, including all configs, mods, ephems and interps. Special deal for those who buy tickets to the Bonfire and Dismemberment parties as a single package. Free wine and hummus at both events.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply