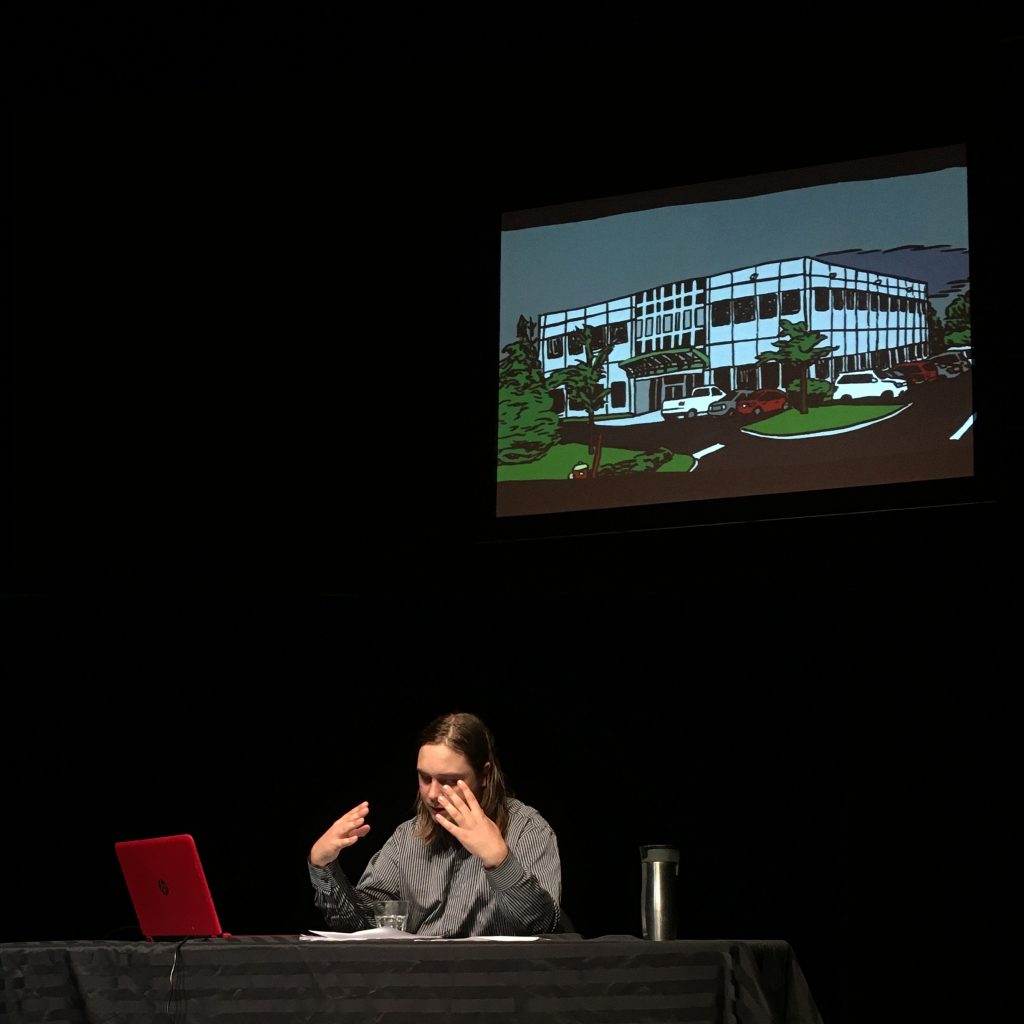

In May, Conundrum Press published my second graphic novel, The Water Lover. The Water Lover is an adaptation of a hand-drawn slideshow I have been performing since 2017. Hand-drawn slideshow is a term I use to describe the comic readings I do. I use this term because these works are made for the performance, not for the page. They are comics intended to be seen live, and, as such, they are developed in a way that plays to the strengths of what a slideshow can do versus what the page can do.

I started doing hand-drawn slideshows in 2016 to reach a broader audience. I live on Canada’s east coast in a town of 5,000, nowhere near any active comic communities. But there are a lot of artist-run centres, independent music festivals, and fringe festivals near me. My plan to get by as a cartoonist was to make work that fit in these spaces. The contemporary art community is a particularly good place to make work for, as there is a nationally recognized fee schedule that establishes the minimum amount it is acceptable to pay an artist for any given activity. For performances, this can be as much as $400.

The approach I take to making slideshows was developed when I was figuring out how to make my first show. While working on it, I saw a reading by a cartoonist online, and he did this thing where he stopped to describe every panel as he read, even if it was totally inconsequential to the story. This constantly interrupted the flow of the story. So, the general approach I have taken with slideshows is to acknowledge the projected drawings as little as possible. I write stories for performance to be totally understandable through the words spoken in performance, and I use drawings to interact with those words, illustrating them, providing unsaid information, and occasionally contradicting them.

This approach is one that’s worked for me. I’ve found it deeply satisfying to make comics for the stage. Having to be physically in front of my audience has helped me develop my voice in a very different way than writing comics for Instagram has. It’s also allowed me to bring elements to my work that I couldn’t on a page. I’ve often incorporated theatrical elements and sought to blur the line between comics and animation. The sea of possibilities that this opens up on stage is really exciting to me, and, as a result, performing comics has become a significant part of my artistic practice.

It’s my impression comic performances are generally made by others as an afterthought, usually to promote a book, and there are only a few instances I can think of that buck that trend (comic performances are incredibly hard to document, so it’s possible I’m completely wrong about this). The main performance-first comics I’m aware of are ones that premiered at Lyra Hill’s Brain Frame (2014-2017), Ben Katchor’s musical theatre collaborations with Mark Mulcahy, and Winsor McCay’s early forays into the form in the early 20th century.

The performances at Brain Frame are well documented on Hill’s Vimeo account. What’s incredible about these performances is there is such a wide breadth of approaches taken by contributors, and they take comics deep into the interdisciplinary. There are musical elements, experimental sound, video, animation, actors, and costumes. Some performances barely seem to have anything to do with comics, but they could easily serve as the template for the next 50 years of comic performances. The performance I come back to most often is Jessica Campbell’s 2016 one. It’s nowhere near the most experimental work done at Brain Frame, or even Campbell’s most experimental (in 2014, Campbell, along with Aaron Renier staged a 20-minute play, with animal hats and projected backgrounds), but, at times, it includes rudimentary animations, where drawings are projected one after another, suggesting a sense of movement, which deeply influenced my own approach at an early stage. Every slideshow I’ve made has incorporated this technique.

Katchor’s musical theatre works, which consist of stories sung in front of projected drawings, have also served as an inspiration, but only in a spiritual sense. There is little documentation of them online. But still, what is available is fascinating. There’s a 2012 clip of Up from the Stacks, where characters run through panels, accompanied by frantic music played live under the projection. It’s like a silent film screening with a punk band providing the score. The animation in Up from the Stacks is a little more complex than in Campbell’s performance, characters move across an unchanging background in a way that seems to imply the presence of a layered image, and which blurs the line between comics and animation.

That line has been one of the areas I’ve been the most interested in exploring in my own slideshows. In the second part of The Water Lover, I included a 350-drawing sequence, which, thanks to the PowerPoint automatic slide advance function, turns into a choppy minute-long animation. This sequence, which depicts the hands of a call center worker drawing themselves on a small whiteboard they have on their desk, was inspired by Winsor McCay’s animation work. McCay, who is both a pioneer of comics and animation, also pioneered that ambiguous space in-between these two forms. His iconic 1914 animation Gertie the Dinosaur originally began as a performance work that was included in vaudeville shows, in which McCay would talk to an animation of a dinosaur, which would appear to respond to him. McCay claimed that each frame was entirely hand-drawn, and, while watching Gertie, you can see the background and character design subtly shift over the course of the animation. I leaned into the shifts from drawing to drawing in my animation in a way that gives life to the very lines of the drawing. It appears towards the end of my show, after many shorter animations, and for the minute or so it’s playing, I always sense a sort of wonder from the audience, as if they never realized the line between drawing and animation was so thin.

The last thing that has kept me coming back to comic performances is, like animation, something that isn’t easily explored on the page. That thing is variation. I love the fluidity that live performance can contain. Sometimes, I will stumble into a joke or a new wording on the spot that completely changes the performance. Sometimes I’ll just mess up. But, by embracing this fluidity, the meaning of a work shifts and evolves over time. I have changed wording or added new drawings in nearly every performance of The Water Lover, redrawing it in its entirety in 2018. Through this process, The Water Lover has grown and evolved with me in a deeply exciting way it never could have on the page, allowing me to stay creatively engaged with it after all these years. The printed version of The Water Lover represented the most current version of the performance, but since then I’ve continued to perform and change it. The page can’t contain it.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply