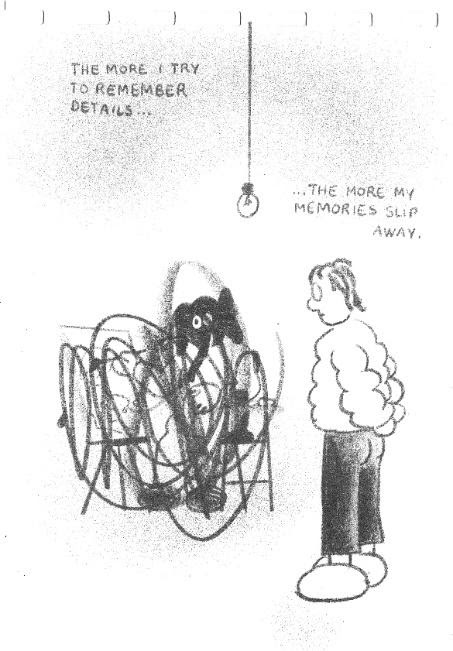

“I don’t recall the exact moment I realized I was a Ghost…”

January 2020, Angouleme Comics Festival: it feels like a lifetime ago.

As I arrived at the airport to board the plane towards Angouleme, I could notice that quite a few people were already wearing masks. Despite everything that was being broadcasted on the news, none of us were prepared for the gloomy, uncertain downward spiral that marks the year of 2020 so far. But it’s still January, and the third case of COVID-19 in France had been detected in Bordeaux, my plane’s destination.

It had been ten years since the first time I visited Angouleme’s Comics Festival, so I had quite high expectations. I had a fully detailed itinerary, a list of all the publishers and authors I wanted to meet, a shopping list of books to buy. Yet, I was quite surprised to notice that, in ten years, things weren’t that different. I immediately recognized the marquees, as well as the abysmal difference in temperature between the inside and outside of them – it was so easy to catch a cold (and that eventually happened). At the end of January 2020, we had not yet understood that this virus was here to stay, even less that a catastrophic pandemic was looming. Just as I didn’t foresee that Angouleme would have been my last travel before the pandemic lockdown, Aisha Franz couldn’t predict how pertinent the subject of her new project – Where is Aisha? – would be for our current scenario.

I bought a copy of Where is Aisha? at Chifoumi Association’s stand (please, check out their projects!). It’s A6 sized and looks like a fancy reporter’s notebook. The cover is made of malleable purple plastic, resembling old picture books I had as a kid. I had been following Aisha’s work for a while on Instagram, and I had already read some of the previous chapters of this new comic published on her account. Just like an Instagram post, Aisha’s comic is read one vignette at a time. You must flip each page, each image like a calendar. Just like a slideshow, an illustrated book, or even a movie, each moment is isolated from the others on a single page and the sequence is created as you read.

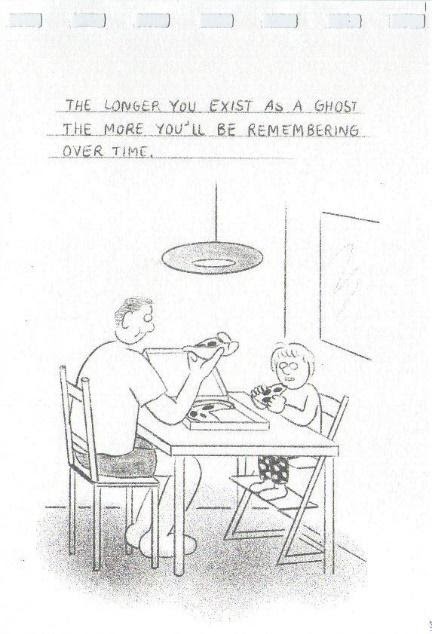

Where is Aisha?, published in risoprint by Colorama, is an evocative yet humorous comic that pictures Aisha herself as a ghost reflecting on her new form of existence, considering its liberties and constraints. Aisha eventually meets other ghosts who instruct and assist her in her new life form, learning that being a ghost is not quite the same as being dead or physically detached.

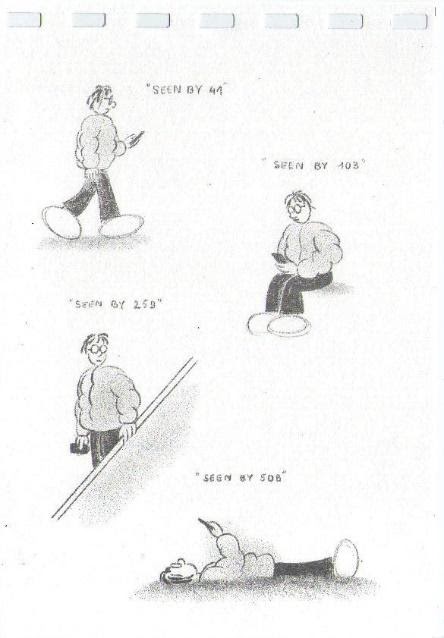

As the story begins, Aisha is already a ghost – she knows it because she can’t interact with anyone anymore – she’s invisible. Ah, and of course, she can float. Aisha keeps wandering around the city aimlessly, until she realizes that her Instagram account is still online and that, somehow, she’s still able to post pictures of herself. She decides to post a selfie, “in order to find out if I really exist.” However, the increased number of views doesn’t bring her any consolation – 508 online strangers who have seen her selfie can’t prove her real existence.

As Aisha starts to accept that she really might be a ghost, someone replies to her posted selfie. Ella, aka ella.mint, the famous Instagram influencer, has requested Aisha to meet her.

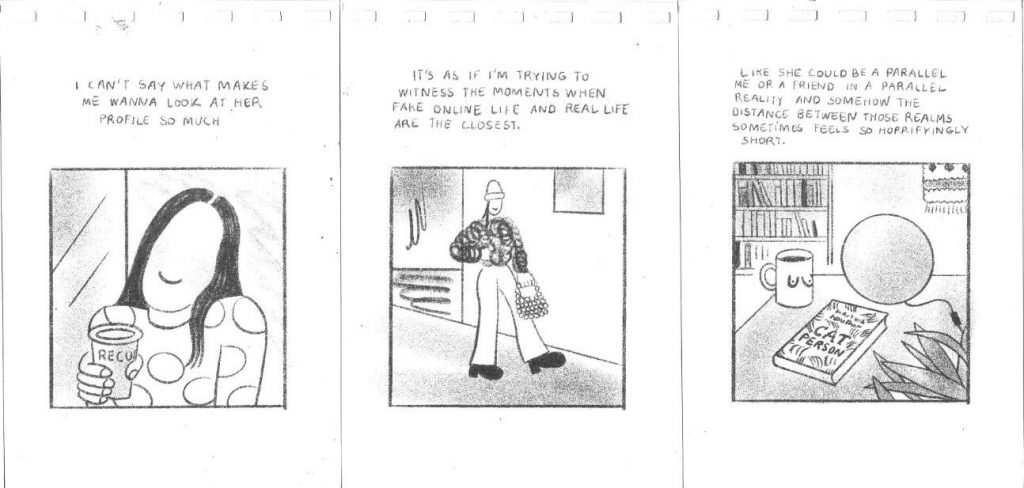

Aisha never met Ella in person, but she feels quite familiar towards her. She has been following her account for some time now, leading her to the idea that she is, somehow, related to her. Aisha, the author, draws a sequence of seven Instagram posts of Ella: Ella posing with a coffee cup, Ella strutting her new fashionable outfit, Ella laying in bed, some random “mainstream feminist” quote. Just like Aisha, I felt like I knew her too. She’s not very different from a lot of other influencers that come across my Instagram dashboard, but no matter how much we may know that the visual and digital representation of a supposed person is not necessarily “real”, our instinct does not necessarily admit the same idea. By seeing these images, and nothing but the images, we intuitively assume that the pictures are a direct reflection of that person’s life, because we have nothing to counterbalance it with. The relationship Aisha created with this influencer is the same we all create with any public figure: we’re not attached to the person, we’re attached to an Image, an Idea, that says more about us than the person it represents.

Roland Barthes, in his 1981 book Camera Lucida, describes the addictive relationship we have established with photographs. Barthes says that photography is “doomed” as a medium because there’s no picture without anything or anyone. Seeing a photograph is always seeing the thing it embodies, and ultimately the effects it produces on us. And since photography is inseparable from its referent, it sometimes becomes difficult (or impossible) for us to see it as an image, but as the thing (or the person) itself instead.

As a ghost, Aisha and Ella are only visible, therefore “real”, as images, or, instead, Aisha and Ella are real because their images can be seen. Nevertheless, it’s the picture, the reflection we can see, not Aisha or Ella.

As a popular public figure, Ella seems to be quite comfortable existing as a ghost. Once they meet, she teaches Aisha the five fundamental rules of being a ghost:

- Let go of the past: try not to stalk your past life, it makes you bitter and lonely.

- Stay away from cats and babies: because they can see you!

- Don’t kill yourself: yes, you can die as a ghost, but you will never be fully dead. Instead you’ll lie in a permanent state of limbo.

- Give as little information as possible on your location: Because we’re very visible on camera and social media, and some people are trying to catch us;

- And, of course, take advantage of your ghost abilities: floating, invisibility, etc.

But only after understanding the rules and accepting the fact that she is a ghost, Aisha starts to seriously reflect on what it implies and what it really means to her own existence. Contrary to what would be expected, a ghost is not necessarily a dead being. As a ghost, Aisha keeps having the same feelings and needs as a living human being; she feels hot, she sweats, she feels tired, she gets hungry. Ella shows Aisha that being a ghost has its own goals and responsibilities. Each member of Ella’s group has specific talents and skills which, combined, lead to impeccable teamwork to frame government conspiracies, leak private information, etc.

As Aisha observes her ghost peers taking advantage of their invisibility to create a positive impact on society, many of the concerns she had once alive are brought to the afterlife: am I still able to make any difference? How could my talents, as an illustrator, contribute to anything useful and impactful?

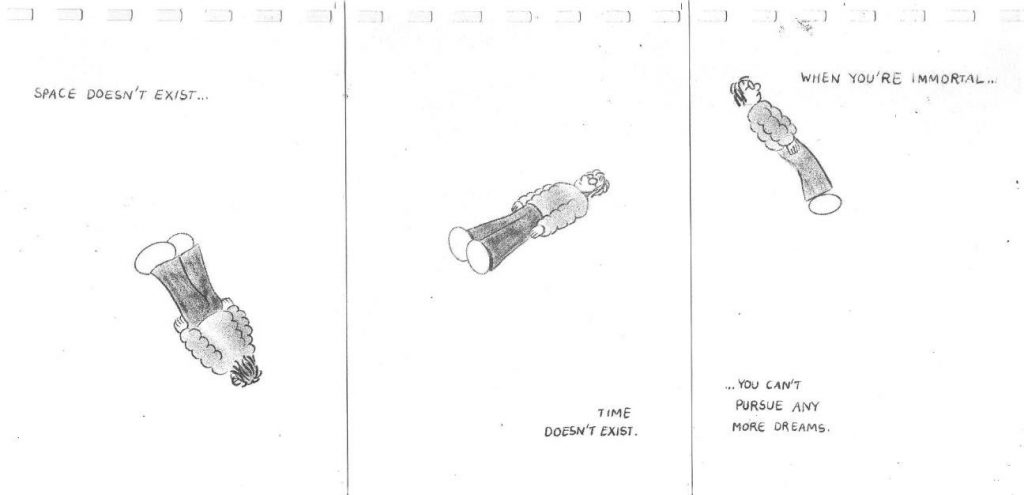

Aisha is no longer concerned with the end of things, but with the everlasting and unchanging eternity that she foresees. Having an end, as bad as it may have sounded before, gives one goals, dreams to aspire to, things to finish before a deadline.

“Being a ghost is basically waiting and waiting and waiting without anything to wait for.”

Halfway through my reading, now in August, I remembered the first weeks shortly after the pandemic was declared. I recalled the lockdown enforced by many countries, mine included. I remembered those first weeks when the internet and the media were the only windows and evidence of an outside world, even though it was a grotesque, frightening, and hardly promising view. I still consider myself highly privileged because I was one of those who could choose to stay at home. More than ever, social networks became an indispensable means of survival. Even for those who didn’t have the habit (like me), it became a regular need to check Instagram, Twitter, Facebook feeds, looking for the latest news or the faces of our friends. Human faces. Birthdays celebrated via Zoom. Performances on the balconies of buildings in Italy. Workout sessions via Instagram stories. After a few weeks of lockdown, people started to compete their apparent productivity. Learning how to bake bread, getting fit, finishing a novel: a simultaneous desperation and focus on showing the world and everyone that we still had goals, a purpose, even if (and because) we were devastated, unemployed, and terrified by uncertainty.

The pandemic highlighted and aggravated the social and economic inequalities worldwide. We weren’t all in the same boat. And as futile and pointless as it still seems, sharing these small, irrelevant achievements is one of the strategies many of us found in trying to establish some “normality” in a world that is falling apart.

And just like Aisha’s ghost, we’re afraid it reformed (perhaps permanently) the basis of human social relations that we have established with each other until now. And after months of attempting to isolate ourselves from others, we may realize that the detachment we usually experience is more than just physical distance.

As a ghost, Aisha struggles that she won’t be able to connect with her loved ones anymore, leading her to a spiral of nostalgia of her past life the same way we might linger on our pre-Covid life: going to places full of people and not being afraid of getting accidentally touched; hugging our friends, holding hands, kissing our family and loved ones. Ella remarks that clinging to past life not only is ineffective and depressing, it also leads one to become bitter, selfish, and lonely(er).

For her to overcome the frustration of not being able to communicate with her loved ones anymore, Aisha must accept that the past won’t come back. The life she had is not going to return, and the future, even if it’s not better, will certainly be different.

“Even a ghost needs meaning.”

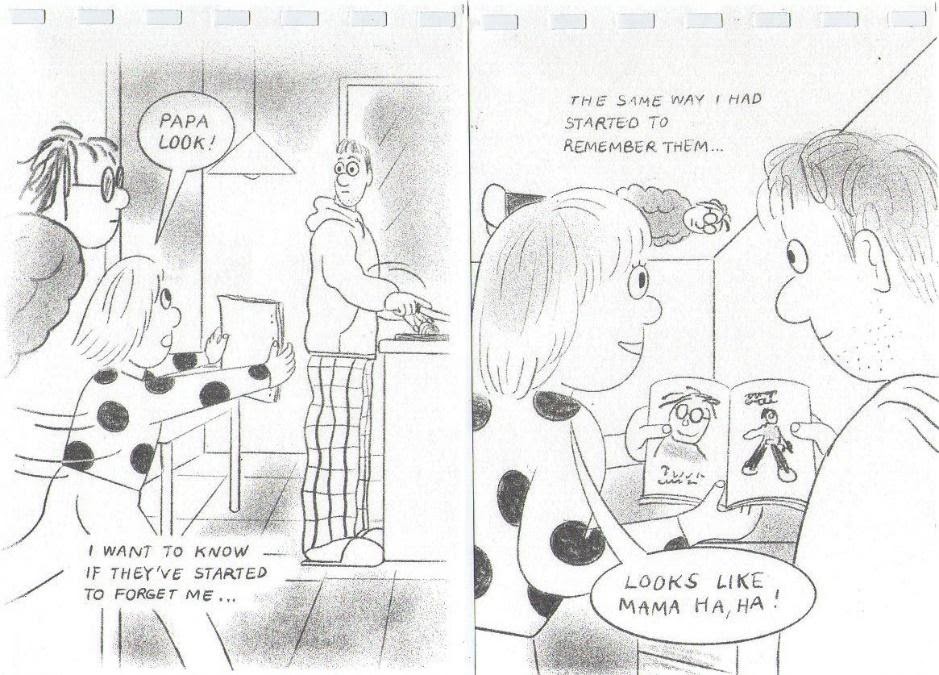

Overcoming grief is part of Aisha’s process to be able to find meaning again. By breaking some rules, Aisha realizes that her skills as an illustrator are actually quite useful: “Turns out, everybody needs stories…”

Through storytelling, Aisha can remember her own goals and regain the will to act. Even though she’s not able to communicate as a living being anymore (no more direct interactions), she can leave her zines, her drawings, and her comics for her loved ones to read. She can choose how to tell the story.

The last chapter begins with “Fuck Rules!”. Aisha shows us all the cool things about being a ghost: Instead of seeing ghostness as a set of limitations, the author tries to accept her new circumstances as a different phase, a new spectrum of opportunities, a different perspective on the life she had and the life she will lead: “Ghostness is about transformation and new possibilities”.

It doesn’t mean that she must let go of her past, but instead, move on from it, within it. Aisha focuses on all the things she can do, instead of what she wished she could still do, even though she still can’t recall how she came to be a ghost.

Storytelling is a form of creating sense and purpose. By lining up a series of events linked by causality, we’re telling ourselves that things do happen for a reason and, sometimes, we can act upon them. We need happy and fulfilling ends because we need to tell each other that there is a goal, and it’s good, and it’s going to be okay.

Our existential friend Sartre once said that life is pointless indeed, but it’s up to us to give it meaning and value. It’s up to us to decide what’s worth living for and fighting for – and its significance lies in the act of choosing, in the deliberate action, and not in the thing itself. How can one, as a visual artist, find meaning beyond the image, if it’s image that is the clay of one’s work? And does image work necessarily mean that its value lies solely in the merely visible? Otherwise, as Lynda Barry says, an image can also be a powerful source of faith. More than a picture, a photograph, or a painting, an image can be anything that we attribute emotional meaning, the same way a little kid believes a stuffed toy is their best friend.

Maybe I’m just rambling, and this is all about the utter feeling of loneliness, about being able to see everything but not being seen by anyone? When we are embedded in our loneliness for too long, the universe becomes self-centered. For me, it is another way of becoming our own ghosts. We forget the true scale of things; our judgment is unreliable. The world out there, people, cars, buildings, animals, all have the same dimensions because they are all equally remote.

I’m not looking for a solution or the truth. Personally, I believe that when looking at things it’s always a matter of perspective. Aisha Franz, however, knew how to put on paper the desperation and the bliss that is in the quest for meaning, for life.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply