A temporal anchor: every Hebrew year (354 days, on average), on what any Good Patriot will gladly and unquestioningly celebrate as Independence Day, the Israeli Air Force leads a countrywide flyover, crossing the country and showcasing its technological advancements to the awe-struck masses. It is, in its own way, a celebration of progress, technological if nothing else—but the question hardly anyone dares raise is simple: What does this so-called progress serve? What does this spectacle celebrate? The answer, just as simple: Independence Day will soon end, but for the next 353 days it is these vessels that will engage in a decidedly-less-celebratory flyover, one that will leave behind rubble and grief and a body-count, all of these either justified or completely ignored by those good patriots, and you should celebrate the fact that you won’t be on that receiving end. But these questions and answers, simple as they may be, will not be uttered, let alone heard; they will be replaced by silence, filled by the song of jets piercing the sky.

I’ve been thinking about Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle again, lately. Or, in truth, I haven’t stopped thinking about it, not really, since I read it, and since I first referenced it in my first SOLRAD essay over a year ago (ah, how time flies). It is increasingly impossible for me, I find, not to see its warnings at most turns, especially in the entertainment-art sphere I occupy. Juvenal’s condemnation of the Roman populace that had abandoned heroism in favor of “bread and circuses” has become even less than a cliché, but it is where Juvenal finds judgment that Debord finds urgent warning. The two men appear to agree that the “people” (a completely different construct for each, separated by some hundreds of kilometers and some 1,850 years) are “interested” only in palliation and base satisfaction, but they come at it from completely different lines of reasoning and directing the blame in completely different directions, Juvenal interested as he was in the celebration of system (imperium, fasces, legiones in his own words) and Debord interested in the dismantling thereof.

Fascism, like all states of oppressive dialectic put into practice, relies on the sustained existence of two classes, both of whom engage with a false reality: the distracting class and the distracted class; the performer and the spectator. This dynamic is necessary for the survival of hegemony: the distracted class must either be completely unaware of its oppression or aware but trained and susceptible enough to justify its pain; the distracting class must be constantly aware of this state in order to sustain it, either by presenting everything as wonderful and perfect or by faking the recognition of its problems while saying “ah, but we’re working on it and, besides, who else do you want to take care of you? Those guys (meaning anyone but us)?”. Propaganda is, of course, the most effective vessel of both paths; the state parade, with its reliance on and celebration of excess, is the champion of diversion-propaganda—and who better to depict excess than neo-mangaka Yokoyama Yūichi? Plaza, the latest book by Yokoyama to be published by an Anglophone publisher, is all about Juvenal’s bread and circuses, and all about Debord’s Spectacle; where he lands between the two, however, is far harder to pin down.

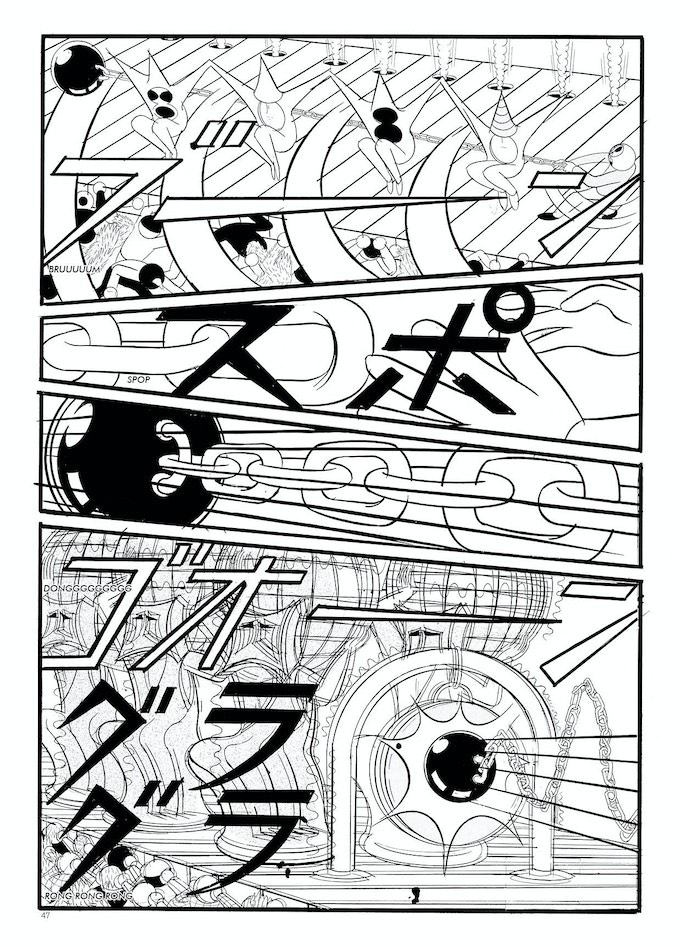

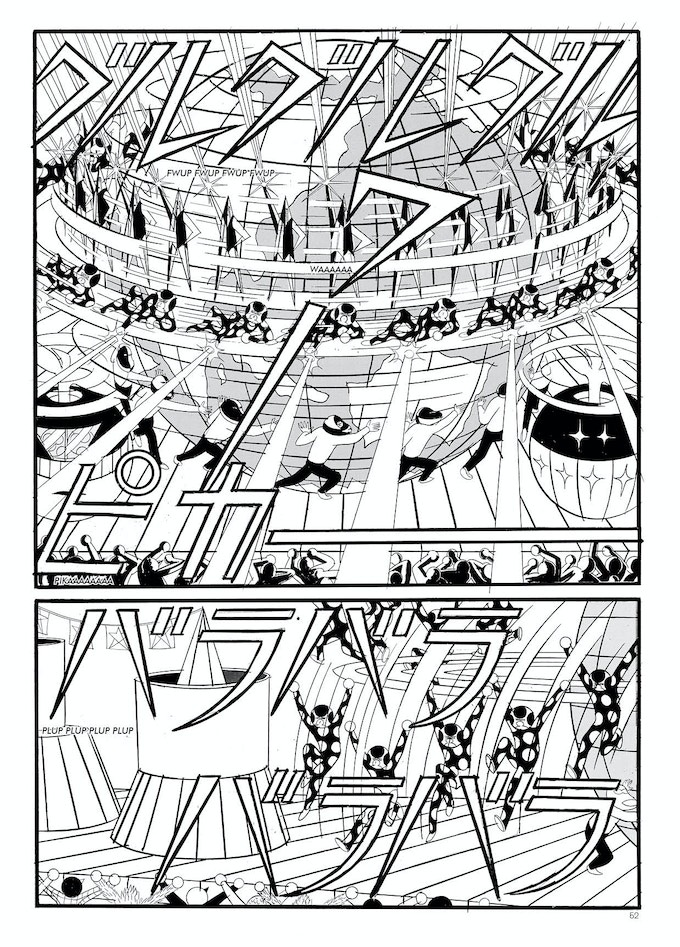

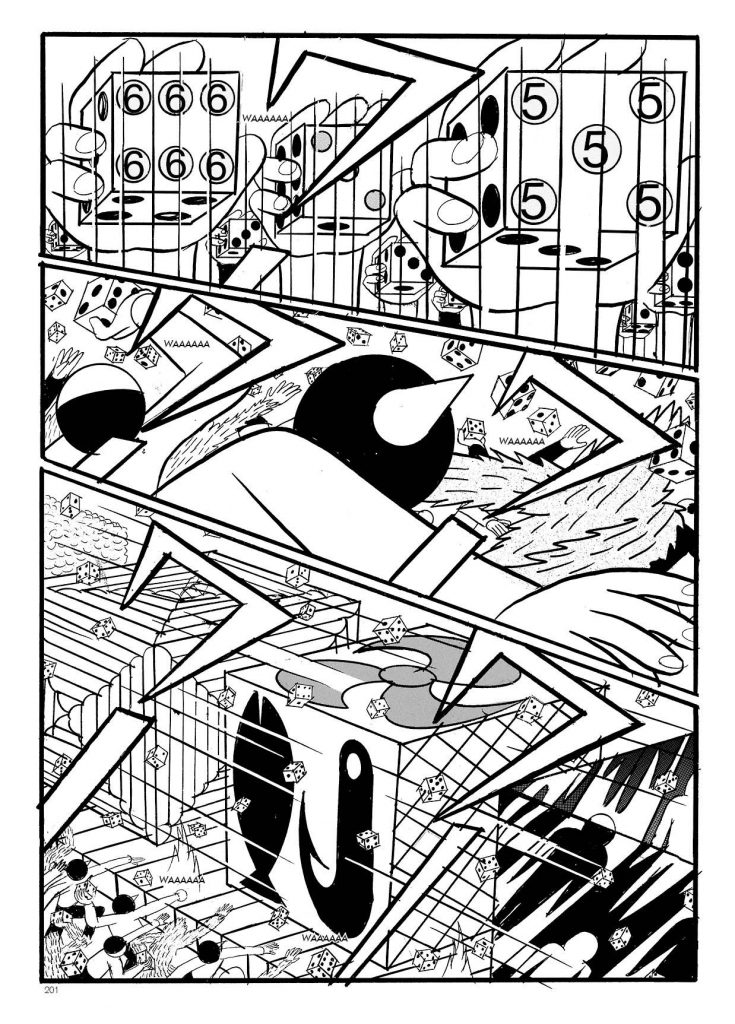

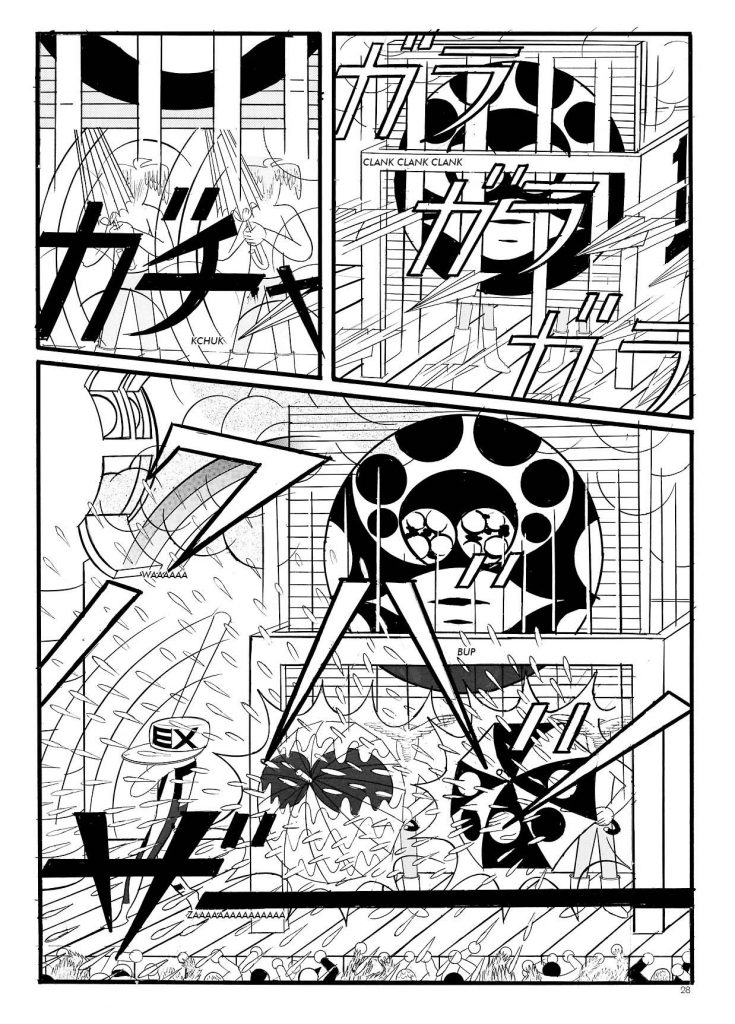

When discussing the auditory/verbal component of comics, there is sometimes a tendency to conflate “wordlessness” with “silence,” sound being perceived as contingent on phoneticizing. You can leave it to Yokoyama to demonstrate, once and for all, that the two are decidedly not the same; there is not a single word of narration or dialogue in Plaza‘s 225 pages, beyond the awed onomatopoeic cheers of the crowd (somewhat perplexingly offered in small-type translation on the art alongside the bombast of the Japanese sound effects) and the inscriptions written on the set-pieces and displays (which other comic will give you an oversized bunch of grapes that reads “WE ARE COOL” over and over?), but if there is one thing this book is not – it’s “silent.” Between the chunky, overpowering sound effects and the proliferation of motion lines, whenever you pick up a Yokoyama Yūichi book, it will likely be the single loudest book you pick up that week.

In this regard, it’s hard to think of Plaza as anything other than the purest fruit of his labor: for 225 pages, the reader “attends” a parade, inspired by Brazil’s annual Carnaval, featuring a great many dancers operating a great many vibrant displays. Such a project is perfect for Yokoyama, as a cartoonist who is interested in the temporality and kinesis of comics and completely uninterested in narrative components such as emotion and character development. It is elevated by his careful balance between the overall simplicity of lines and the density of objects: he does not bother with overwrought rendering, making do with economic recognizability of objects and putting most of his efforts into a “clutter” both tangible and sensory. There is a lot going on in every single panel, but there is always an order to it, a clarity that rearranges the space in the eyes of the cooperative reader.

His ethos, as such, is the ethos of the absolute outwardly: any insight into the world depicted is only sensory, “compensating” for the detachment from interiority through his technique of sensory overload. It’s a working formula that doesn’t really need any fix or improvement—his comics are certainly not for everyone (his ethos of alienation and disregard for conventional plot are a better reader-filter than most), but I find it impossible to read his work without being completely captivated by the overpowering energy of it all, and it is precisely that divergence from convention that emphasizes his love and thoughtfulness for craft and form. It is not “easy” to read, insofar as the levels of sheer sensory intake are higher than pretty much any given comic you will find at your local shop, but it’s all the more exciting because of that.

It is also this alienation that grants Plaza a deeply eerie undertone of discomfort under its celebratory surface. As mentioned previously, Plaza was inspired by Brazil’s Carnaval, but where the two diverge is at the step that immediately follows initial inspiration: contextualization, or, more accurately, recontextualization—or, more accurately still, the intentionality of a lack thereof. Traditionally, when approaching a story with some anchoring in our literal reality, there are two possible approaches: either a direct adaptation, one that preserves the context and circumstances that led to the work’s real-world parallel, or the construction of a parallel-but-separate context that feasibly led to the same (fictionalized) culmination. But this is, of course, traditional convention—being precisely what Yokoyama is not interested in following.

In this particular case, it’s worth examining the context of Carnaval: in the 2017 interview conducted by Yamase Mayumi included as backmatter in the English edition of the book, Yokoyama discusses the Brazilian Carnaval in his usual delightfully-offhand tone, saying “You probably know about Carnaval in Brazil, where everyone puts on these outrageous costumes and dances in a big parade. Why they do that exactly, I don’t know, but I imagine it’s meant to express gratitude to their god.” In his lack of research, Yokoyama is not incorrect, the Christian carnival being largely a Christianized Saturnalia, the Church affording a three-day period of careless relish and license preceding Lent; what he doesn’t say out loud, however, is the inherent bond to nation: the Brazilian Carnaval may on paper be just another incident of that Christian carnival, but in practice it is by far the most well-known one, the word having largely become, at this point, synonymous more with Brazil than with Christianity (although, to be fair, Yokoyama did not say if by “god” he refers to that of religion or that of nation, if the two can be said to be separate).

All of which is to say, the real-life modern-day Carnaval, like the larger traditional of carnival from which it emerges, is deeply rooted in the specifics of tradition both religious and national. With Plaza, Yokoyama strips the carnival of the contextual specifics that birth it, leaving behind something of a hollow shell—a spectacle of overwhelm that, in its bare nature, turns that overwhelm into not just the means but the end as well. The celebration at the heart of Plaza then becomes a celebration of a post-structuralist horror of sorts: a signifier completely isolated, with nothing to signify inside or outside of itself. Alongside that sensory aspect mentioned previously, this is the other way in which the book is the complete fulfillment of the Yokoyaman ethos: in his rejection of interiority, the work somewhat inherently becomes the Debordian spectacle that engages only in the exterior. There is no rational to it, no beating dialectical heart—and the absence of dialectic, as it always does, becomes dialectic in itself.

This is what I mean when talking about the eerie nature of Plaza‘s anti-story: hollowed out of its context and consequent emotional impact, what is left of the baroque grandiosity of its ersatz-Carnaval is an absurdity, a convocation in celebration of nothing that exists beyond itself. It is at this point of absurdity that the reader is tasked to infer the rest of the world they are reading, the world realized by their holding it in their very hands. To me it reads almost like a form of hubris: the cartoonist is close enough to the “scene,” attached enough in his depiction of the tactile and sensory, to leave the reader no choice but to submit to the excitement and overwhelm, but distant enough in his omission and flattening to make it clear that there is hardly anything of substance to this excitement—that, tempting as it is, any sufficiently cautious attendee will take a step back.

This muted terror is amplified by the frenzied concatenation of objects and set-pieces on display: as promised by the author himself, this book displays one thing alone—the continuous parade, in all its wealth of costumes and props. Many of these props are harmless and innocuous: automatons shaped like comedically large fish and frogs, cuckoo clocks, martini glasses, large reeds of bamboo. Others, though, are decidedly less so, prompting the reader to ask why, for example, is there, in this bacchanalian pseudo-world, a row of tanks, or an automated machine gun? Are the rockets launching from their platforms ones of exploration or of decimation?

Precisely because of this contrast it is hard for me to view Plaza, and the world it contains, in any purely celebratory light: the ostensibly casual depiction of these objects, of the violence they connote, raises the question of what exactly happens when the party is over, and what realities make this act of celebration possible. I am almost tempted to compare it to Le Guin’s city of Omelas, except Le Guin’s narrator at least clarifies that there are no soldiers in Omelas, no triumph against an outer enemy; the torture of the child in the cellar, described in Le Guin’s story, is more visceral, more intimate, than the psychological distancing of war and soldier, a violence directed inwards, justified as the necessary costs of the preservation of ideology. Yokoyama’s world shows an ideology preserved similarly, without even bothering to dwell on the costs.

And, in a way, that almost enhances the torture, the cruelty of it all, in that it offers a completely sanitized view of that violence; the tank and the gun celebrated in the same breath as are the frog and fish, the act of shooting synonymized (or at least equated) with the act of dance. And, as said previously, the absence of dialectic becomes dialectic in itself—this task of ignoring the price becomes part of the price itself, as it requires an immense focus on anything else: one can only hope that a moment of anagnorisis comes when the attendee will be confronted by what they had theretofore been escaping, at which point this spectacle will become its own form of guilt and torture. But, alas, hope rarely overlaps with reality when it comes to this type of situation.

It is quite possible, of course, that none of what I have said for the past 2,000-odd words is supported by the text in any real way, and that much of it is, in fact, projection; the hollowness and blankness of Yokoyama’s work is arguably the most convenient projection platform in comics. To paraphrase the cartoonist’s own words, why Yokoyama Yūichi made Plaza exactly, I don’t know, nor do I know what god it is meant to express gratitude to, if at all; I do not think, based only on his own statements, that he ever set out to make any political statement with it (nor do I know his views or the extent to which they overlap with my own). But I do know that it is a singular wonder of a comic, beautifully drawn and astoundingly realized. In more than one way, Plaza is spectacular and explosive, as well as one of the most inadvertently-urgent warnings comics have seen in a long time, packing one hell of a punch for anyone willing to prod under its surface. What other choice do I have but to be deeply thankful and excited by it?

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply