I can start this review by talking about how the past three years or so have, at the very least, afforded many of us a grim opportunity to articulate our personal politics—our tolerances, our limits, our modes of praxis or performance—amidst one global crisis after another. I can talk, too, about the neoliberal habit of praising political suffering as a catalyst for great art that emerges from a personal urgency. I can even talk about my new rule, which dictates that if Dave Sim (dispenser of opinions such as “[women are] voids without a glimmer of understanding of intellectual processes”) offers a politically-tinted endorsement of a comic that’s as good a sign as any that I will not enjoy that comic. I can talk about a great many things, and indeed I have in since-deleted drafts of this opening paragraph. But nothing feels right, because sometimes nothing is right.

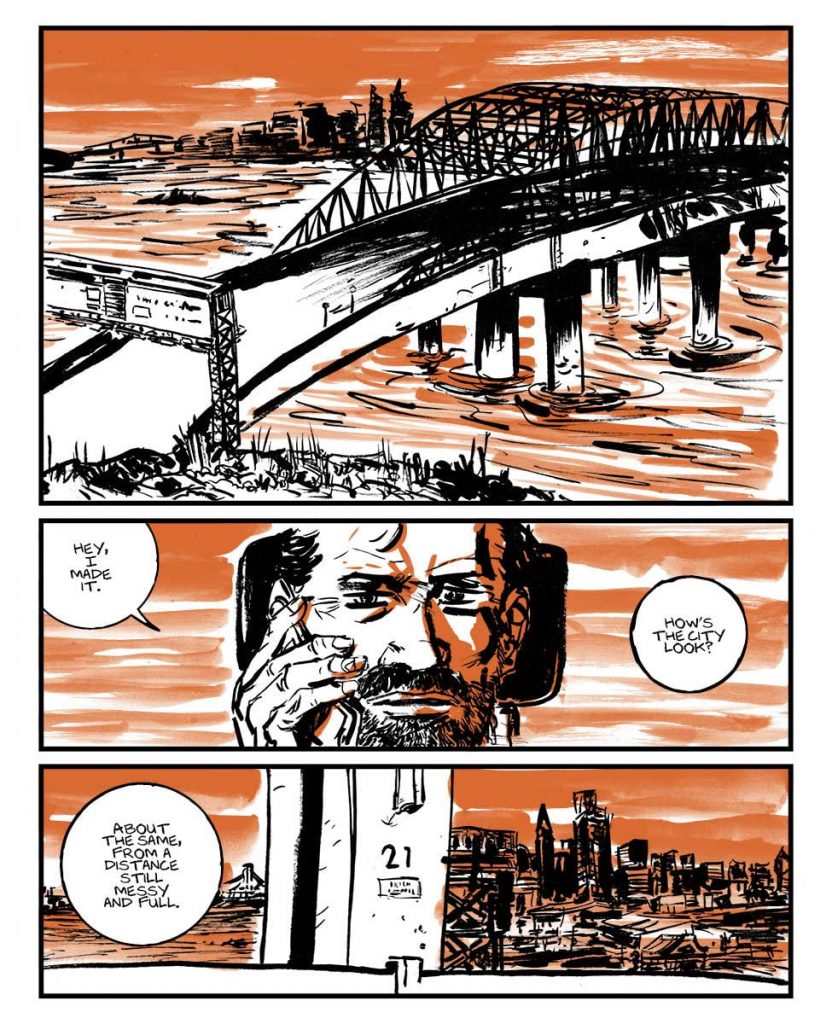

This certainly appears to be the case in the world of House on Fire, the latest outing from Living the Line, written, drawn, colored, and lettered by Matt Battaglia. The premise is simple, its plot streamlined in order to give space for its atmosphere to assert itself: in a near future defined by its dystopian nature, a husband, caring for his sick wife, ventures out of the relatively-safe suburbs into the dilapidated city in order to barter for medicine for his wife, only to be confronted both by the army that guards the city and by the merciless mobs that inhabit it. The whole affair is coded vaguely enough, out of what appears to be a desire to garner reader engagement by way of pure relations: not much is known about either member of the core couple beyond what can be deduced from their yearnings for that “old world” before the dystopia, and its political underpinnings, with two exceptions, approach the archetypal.

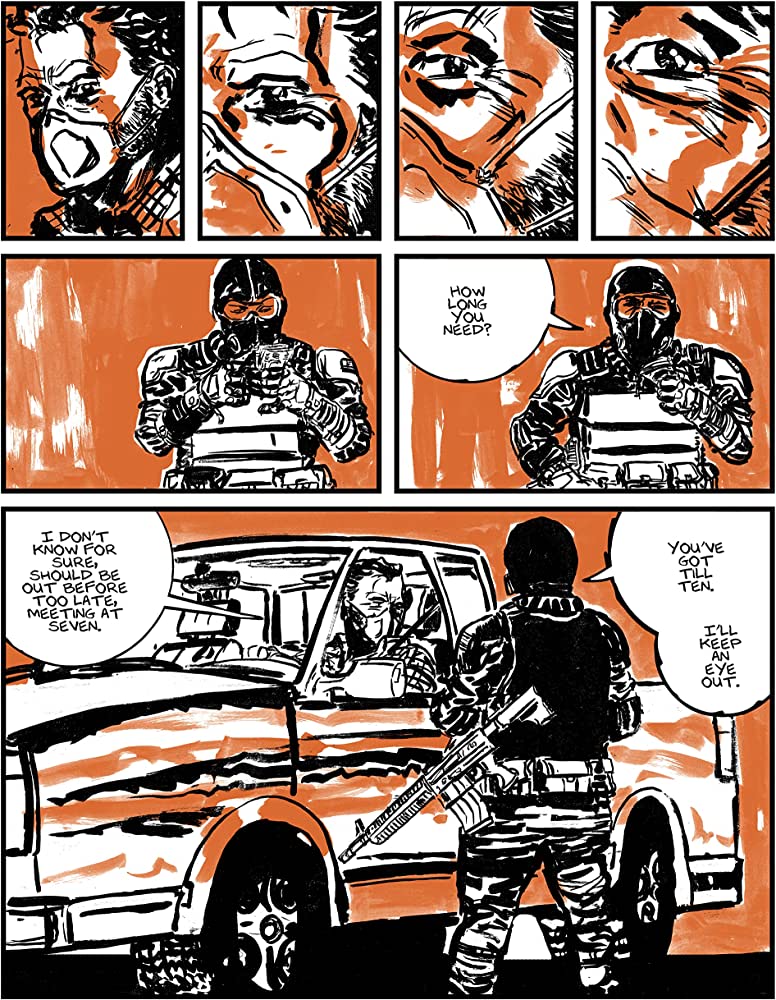

Battaglia belongs to the Paul Pope school of cartooning, and, while I am not particularly a fan of Pope’s oeuvre, Battaglia makes that vibe work. With rich ink delivered by a restless brush, the hopelessly chaotic, broken nature of the world is palpable, smothering; aided by the professed avoidance of any reliance on reference images, the visuals of Battaglia’s world certainly come alive, with a vitality and a spontaneity that is almost unimpeachable. The artist, too, manages the feat of walking the fine line between “chaotic” and illegible with an unusual confidence, breezing his way through it. The tense atmosphere of the world is amplified by its duotone approach to colors, with a rich orange conquering the air, giving the feeling of an eternal hopeless twilight. Sim, for all his faults, is precise in his artistic diagnosis of an invented “photo-impressionism,” as Battaglia’s work really does manage a precision that goes beyond the atmospheric: at least on the visual level, his world feels real, anxiously lived-in with a distinctly Frank Miller-esque quality. Simply put, I’ll give the book the credit that it at least tentatively deserves: Matt Battaglia is one hell of an artist. This is not a claim I can in any way refute, nor do I particularly intend to; when it comes to a “pure” form, one whose merits are supposedly unaffected by its political affiliations, Battaglia’s sequential artwork skills are great.

But, of course, art does not work that simply, and treating politics as a mere pollution to be evaded and ignored is not a modus operandi I care to engage in. So, sure, the art is verifiably beautiful, but it carries with it its own baggage. Two key context clues to House on Fire‘s political landscape are an allusion to military aggression in Europe, with attacks on Poland and stalled talks between NATO and the “R.C.C.P.,” and respiratory masking, with signage encouraging masks by simply reading STAY SAFE. The book clarifies the precise historical moment that conceived it, and continues to spread out from there, as if daring its reader not to make the association. In itself this would have been fine—if not for the actual messaging that it offers.

The imagined Russia’s aggression is unremarked upon, serving more as a backdrop than a dialectical fulcrum, but masks do bear significance; it is noteworthy that the protagonist only wears his mask while at an armed-guard check-point on entering and exiting the city: masks are shown not as a precautionary measure but as an indicator of one’s willingness to abide by the dictates of the evil regime that, one must infer from the overall framing, uses rhetoric of safety and health to induce some sort of collective docility. Coupled with the fact that real-world governments only briefly enforced masking and vaccine mandates (the publisher’s note at the end of the book mentions that the book took about a year to get from a very rough pitch to a the printed book that came out March 2023, and as far as I can recall by March 2022 the U.S. government had largely abandoned any façade of masking enforcement), it is very difficult not to read this book as a piece of reactionary hyperbole that immediately dates itself through its fears, viewing, as it does, any health-minded restriction as violent brainwashing.

Now, I’m as suspicious of my governing forces as any post-1968 leftist who has read a small handful of theory, but I am also wary of veneration of an abstract individual liberty, and especially during the pandemic we have seen the limits of grouping “anarcho-” political groups together, because the libertarian right and anarchist left oppose government for diametrically opposed reasons, the former wary of any constraint whatsoever and the latter understanding that enforcement of these constraints in practice only depends on the class one belongs to. So, if we, by way of the book currently being discussed, are using COVID restrictions as some sort of litmus test, even if one suspects government and its enforcement (which I certainly do), the key question would be “But do you believe that the individual should restrict themselves of their own volition in order to keep his surroundings safe?”; House on Fire‘s answer appears to be a resounding no, which is odd given that its key theme is the protection of one’s own, and that the protagonist’s wife is, in pandemic lingo, immunocompromised (although, to be entirely fair, no pandemic or such similar event is explicitly mentioned, which makes the urgency of masking even odder beyond its necessity in relation to the message).

Even if you do not view the book’s kneejerk libertarianism as a fault in itself, it does not appear to hold up according to its own logic. The book may open with an epigraph Ephesians 6:12 as something of a rallying cry against the evils of oppression, but the world that Battaglia fleshes out does not appear to frame the oppressed as particularly worthy, either; it’s the armed curfew check-point officer who affords the protagonist a kindness by letting him into the city (even if the protagonist slipped him some money, he was still understanding enough to take the bribe – not exactly the picture of oppressive rigidity the book appears to warn against), and a masked assailant, unaffiliated to any well-organized militia, who attacks the protagonist after he’s picked the medication up. Promotional copy promises a “fallen world, where fear is rational and obedience your only refuge” – but it is unclear whom one might need to obey, and its fears seem to be directed not only at the government at every other living being (in this way the Frank Miller comparison is particularly apt, in a passive refusal to examine one’s implications). This is, to be sure, a thoroughly-documented political stance, but it’s also one that is nihilistic to the point of utter self-obviation.

In caring for his wife, the protagonist bribes a soldier and kills, in what might be justified as self-defense, one of his urban assailants (drawn, one might point out, with distinctly Black facial features) after telling the other one to run, having already largely defeated both by way of armed intimidation. By the end of the book, when the protagonist appears to give up all hope and set his own house on fire, his sick wife inside, while mouthing a quiet and truncated “forgive us our trespasses,” it does not feel like a recognition of one’s own sin: it feels like a performance of the final nailing of the coffin of the world, consequences be damned; having trapped itself in a tribalist conservative “How far would you go to protect your own?” narrative whose enemy, it would appear, is propped up with the sole purpose of enmity in mind, the book carries the narrative out to its logical conclusion: if I can’t protect them, surely they’re better off dead.True, art is typically more than its ostensible politics, but even if you can enjoy art that is politically opposed to your own values (another one of those classically-liberal truisms I am personally not sure about, but if my good friend and fellow SOLRAD critic Tom Shapira can enjoy John Milius’ 1982 movie Conan the Barbarian as much as he does I am willing to suspend my disbelief), but in House on Fire Battaglia is all too eager to be eaten whole by his own messaging. What could have been a fine run-of-the-mill dystopia was undermined by its attempt to demonstrate its perceived urgency, leaving itself no choice but to answer, stutteringly and without much conviction, the question into which it calls itself. Opening on a rallying cry and ending on a truncated prayer, it is unclear that House on Fire finds any conviction in either; indeed, it is unclear that it finds any conviction in anything at all.

Leave a Reply