A worthwhile question: what do we talk about when we talk about ‘paranoia’ in the context of art? We may talk about Thomas Pynchon, whose run-on sentences and digressions bombard the audience with signs and symbols, whether or not these figure into the actual plot itself. We may talk about Feldstein and Krigstein’s “Master Race” (the single best short-form comic in history, in my opinion), whose ending offers two opposing readings — either the man that the ex-Nazi Reissman sees on the train really is a survivor of the Nazi extermination camps, or Reissman is so caught up in his guilt (even if he still believes in the Nazi ideology, he knows very well how Nazis are looked upon in the War’s aftermath) that he sees it all around him; the ending may remain the same, with Reissman falling onto the tracks and dying, but that moment of ambiguity shifts the center of narrative gravity, and the work is all the stronger for it. To me, ‘paranoia’ in art, like the broader category of ‘weirdness,’ is a matter less of aesthetic (though that certainly helps) than of the place of the reader: for a work to be considered ‘weird,’ the reader should ideally feel that they don’t have a total grasp on it — not merely on the narrative level (it’s all too easy to resort to the end-of-chapter gasp! moments of Urasawa Naoki) but on the deeper thematic and exegetical level as well, there should ideally be not just an element of withholding but, also, at the same time, an element of addition, of varying levels of pertinence and plausibility, sending the reader into confusion and forcing them to figure out for themselves which parts are, in fact, part of the story’s reality. Ideally, the work should never state outright what is ‘real’ and what is not; interpretation (subjective, coming from the reader), not explanation (authoritative, absolute), should be prioritized.

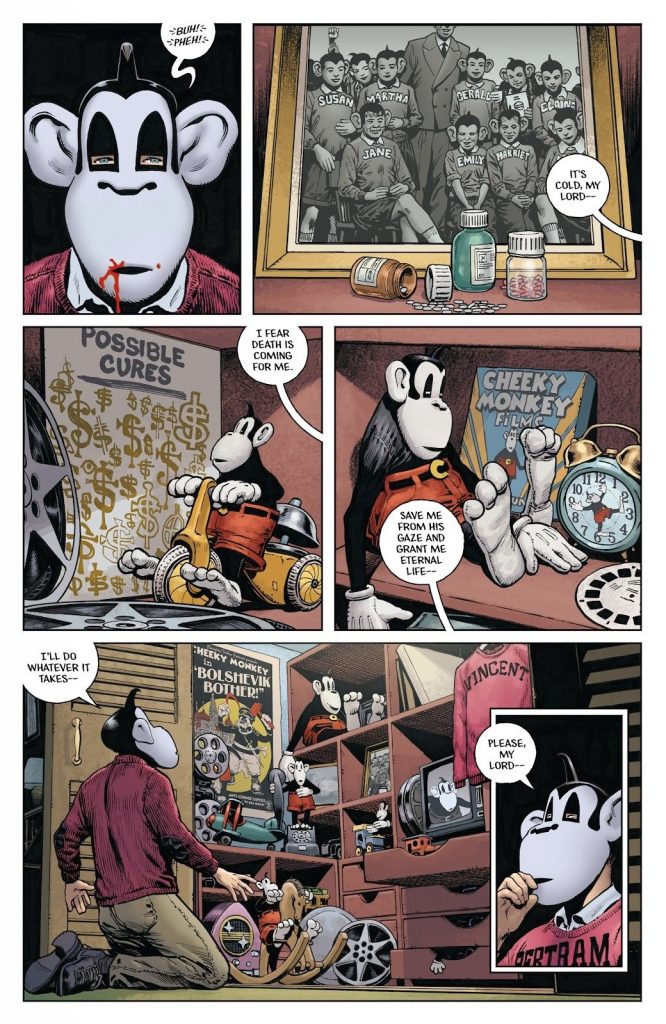

Paranoia, it so happens, has a crucial — even titular — role in the work under discussion today. Originally released in six single issues and then collected in softcover by Dark Horse Comics this past April, Paranoid Gardens is the latest effort from comics-writer-turned-rock-star Gerard Way with frequent co-writer Shaun Simon, with art by Chris Weston, coloring by Dave Stewart, and lettering by Nate Piekos. The book’s protagonist, Loo, is a nurse at Paradise Gardens, an isolated (and sentient) care facility which tends to “aliens, ghosts, superheroes, and more creatures”; she has special healing powers — though these sometimes backfire and kill what it is supposed to heal — as well as amnesia, not knowing who she was or what she did prior to her arrival at the Gardens, four months prior to the story’s start. Meanwhile, Dr. Zerc, the terminally ill director of the facility, finds himself wrestling against the existential rules of the Gardens — isolation from the world at large in exchange for care and healing — as he seeks to trade the Gardens’ long-term viability for his own personal survival. On Loo’s side, the mystery surrounding her identity — a mystery upheld by the whole staff — flares up when a superhero arrives at the Gardens and claims to recognize her; on Dr. Zerc’s, salvation comes in the form of “The Church of the Unenlightened Light,” a corporation that wishes to turn the Gardens into a luxury vacation resort centered around its Mickey Mouse pastiche, the commie-busting Cheeky Monkey.

Though by now it has been long enough since my last reading that my recollection of the work is rather thoroughly faded, I can say that some five years ago Gerard Way would have ranked fairly high on my list of favorite comics writers, and that, specifically, it was his Doom Patrol run, written initially by himself and eventually aided by various co-writers and guest contributors, that garnered much of my appreciation. What appealed to me about that book in particular was that, though quirky and idiosyncratic, it was distinctly more ‘accessible,’ to my sensibilities, than the key point of comparison, being the run on the same title by Grant Morrison and Richard Case, which I found alienating despite my great fondness for Morrison at the time. In the Way run, questions were raised but answered rather loudly and clearly, and everything — every twist, every new development — converged toward one all-encompassing thematic statement, being the motto of protagonist Casey Brinke: “Be a bright light in a black hole.” At 19, I found this strikingly poignant.

For better or for worse, it has been quite some time since I was 19. Certain similarities between Doom Patrol and Paranoid Gardens become evident right away: both Casey Brinke and Loo are medical caregivers (the former is an EMT); both books pursue themes of communal care and affirmation, with Doom Patrol taking the more ‘positive’ approach (putting the emphasis on the rejection of societal normalcy and protection of perceived outcasts) while Paranoid Gardens assumes the more combative stance of using capitalism and gentrification as the antagonistic force.

In Paranoid Gardens, however, Way and Simon demonstrate alarmingly little insight about their setup, the nursing home, beyond the broad mechanical concept (being a layer of fantastical remove to be propped up with the sole purpose of its disruption). The patients have little personality beyond comic relief (which, granted, does work on occasion — having two characters talk with palpable titillation about the head nurse changing bedpans and giving inner ear exams is a solid joke), while the rest of the staff is only developed in relation to the main plot. A secret relationship between a nurse and a paramedic is only mentioned for the first time when they are caught by Dr. Zerc (so he can use the secret as leverage to extort the paramedic) and is hardly touched upon in the chapters that follow; the superhero whose arrival serves as the comic’s inciting incident is given no life outside of his tenuous connection to Loo, no backstory, not even a name — Weston’s process notes in the backmatter simply refer to him as “The Superhero,” underscoring an authorial refusal to flesh out components more than is purely necessary.

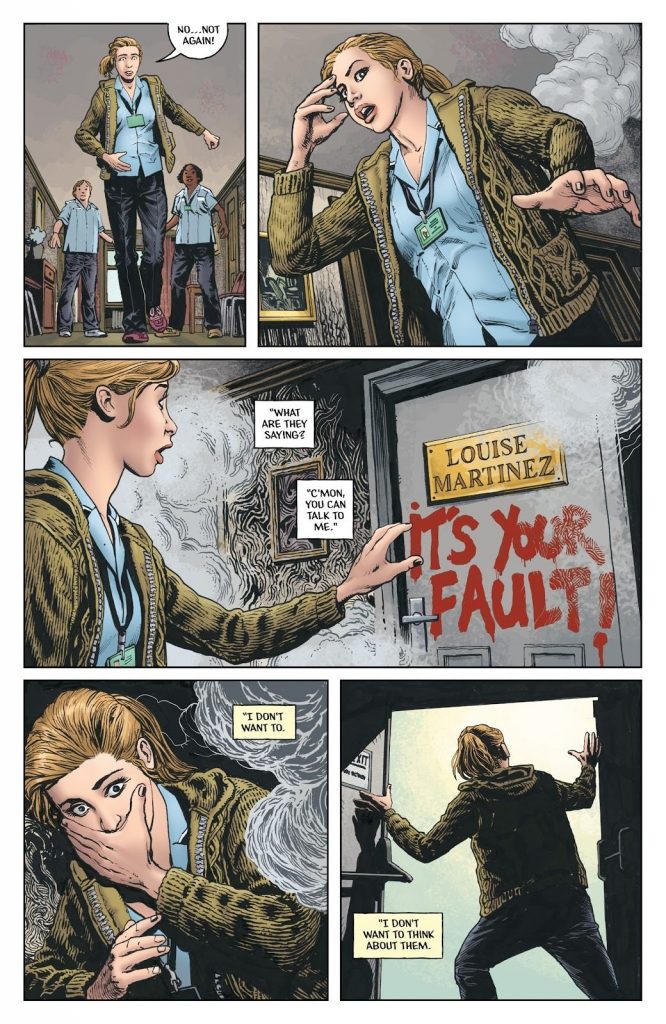

The protagonist and antagonist are both, by and large, similarly one-dimensional. The fourth chapter features a reveal foreshadowed so thoroughly that by the time it is stated outright, it hardly makes a difference, as readers learn that in her ‘real’ life, Loo was a high-school guidance counselor and that one of her students perpetrated a mass shooting in the school. This led the mourning families to put the blame on her for not seeing the signs until it was too late. Here, the dichotomy between Loo and Dr. Zerc is made explicit: the healer who puts others first (and is wracked by survivor’s guilt when the benevolent impulse fails) versus the de facto narcissist who, when the need arises, tosses his Hippocratic oath out the window. These are not, in and of themselves, uninteresting archetypes. The problem is that Way and Simon cannot see them as anything but archetypes: no details whatsoever are offered about Loo’s existence outside of her tragedy, nor anything to indicate that Zerc ever had any better nature, any moral qualms. The book’s central agon is thus reduced to “perpetual victim versus moral invertebrate.”

Moreover, in order to get the reader to ‘side’ with Loo, Way and Simon occasionally wind up undermining their own ostensible points: it’s noticeable that early on in the first chapter a fellow nurse describes Loo as “one of our best,” even though, in practice, she is only ever seen either brushing up against the authority of the head nurse or dissociating to the point of neglecting her duties. As far as declarations of one’s own creative limitations are, then, Paranoid Gardens is a loud and painful one: at no turn do the writers seem to pause and ask themselves why a certain choice is significant to them, nor why the reader should care on any real emotional level; they simply make a mention, usually in stiff (and, often, poorly-proofread) dialogue, and move on. (In particular, one cannot help but look at the use of mass shootings — less a thematic component than a mere expository circumstance — as an attempt to garner automatic political and emotional urgency, regardless of artistic merit.)

In this context, one must consider the antagonistic force, the Church of the Unenlightened Light. Way’s comics, both solo and in collaboration with Simon, often offer such broad (which is to say, often unfocused) representations of capitalism: the narrative of the My Chemical Romance album Danger Days: The True Lives of the Fabulous Killjoys and its accompanying comics revolves around an anarchist group fighting against a corporate monolith that manufactures everything from batteries to robotic sex-workers; Milk Wars, the crossover storyline that Way initiated and oversaw as part of his DC imprint Young Animal, attempts the rhetorical connection between capitalism (via corporate IP) and societal normalcy as an endeavor of oppression. Not coincidentally, however, these themes figure even more heavily, and in a more fleshed-out manner, in Morrison’s own work — Guy Debord’s Spectacle figured heavily into The Invisibles, whereas Seaguy had its own Mickey Mouse riff, Mickey Eye, whose brand of world domination likewise manifested as an enforced collective apathy in the service of capital.

I note this not because I think Way is uniquely unoriginal — Way has often been dismissed as a Morrison derivative, but God knows these ideas did not originate with Morrison — but because these similarities, specific enough to merit pointing out, shine a spotlight on the key difference between the two writers. Despite my many problems with Morrison nowadays, what I can appreciate about them, in comparison, is that the breadth of their referentiality and stylistic influences creates an element of analytical legwork; simply put, the reader is asked — and trusted — to pay attention, to search for patterns and connections. Even if the work falls apart under scrutiny, parsing is nonetheless an active endeavor.

This legwork is distinctly absent in Paranoid Gardens, which, despite its invocation of ‘paranoia,’ is one of the most straightforward comics I have read in quite some time. Here, the welcoming quality of Doom Patrol, an easy accessibility offset by a distinct voice, has given way to narrative prostration. Anything that might be described as ‘style’ is forfeit to ensure that even the most inattentive reader remains in total control, even — especially — when the protagonist is not in control. At no point is there any vagueness, nor even any cheap legerdemain to keep the reader in a state of suspense — only a clumsy thesis statement (the words “the only way out is through” are offered, verbatim, as an insight supposedly profound enough to rouse the protagonist from a hypnotic state) on which the entirety of the narrative hangs. In point of fact, this total aversion toward confusion is a surefire way to make a work of art weaker: by placing them at a position of relative power over the work, the artists take away from the reader’s immersion in the work itself, creating an unbridgeable distance. This is doubly perplexing given the chosen theme of trauma and recovery therefrom, a non-linear process if there ever was one. In portraying the process so frictionlessly, without articulating the depth of Loo’s disorientation, the writers only stand to rob themselves of poignancy.

Similarly, it was in reading Paranoid Gardens that the significance of a certain connection occurred to me: as a young artist, Chris Weston (an artist I’m generally quite fond of) apprenticed for Don Lawrence, something of a titan of the British comics of the ‘60s — an era defined, in retrospect, by technically-accomplished, classically-handsome artwork whose emotional impact was rather uniformly choked out by structural constraints. Another artist who apprenticed for Lawrence is Weston’s contemporary and former 2000AD peer, Liam Sharp. It’s not hard to see Weston’s progression over the years as a movement from one extreme to the other, starting from the heady ‘metal’ stylings of Sharp — hefty mark-making and rendering, ratty inks — and ‘graduating,’ over time, into the solidity, clarity, and textural uniformity of the Lawrence school.

In Paranoid Gardens, Weston reaches the limit of that stylistic avenue, especially where acting is concerned; in essence, the more dramatic or active the character gets, the less compelling the depiction becomes. Consider the above sequence, from the fourth chapter: the black-haired man is the superhero, who has lost his mind after being unable to stop the school shooting; he recognizes Loo, but Loo, whose memory is still blocked, does not understand why. Note the over-the-top contrast between their respective expressions: the superhero appears vulnerable, caring, even well-observed, whereas Loo — the character the reader is supposed to relate to, to root for — is reduced to grotesque histrionics.

This more or less defines his approach to the rest of the book: perfunctory stiffness, with only the occasional glimmer of humanity. A vivid visual communicator, here he is constrained to the most mannered forms of presentation: with one sole exception, his panels are exclusively quadrangular and almost uniformly tiered, with only the occasional inset panel or half-tier; his designs for monsters and aliens are uniformly humanoid, their anatomy consistently upright and bipedal even when their faces are distorted. One wonders, reading Paranoid Gardens, what happened to the heady, heightened sensibilities that Weston displayed in his Morrison collaboration The Filth — another book about dual identities bleeding into one another. Dave Stewart’s coloring is likewise toned down, easy to look at but never vibrant, never glaring except for the most obvious justifications — never, simply put, interesting or additive.

By the time Paranoid Gardens reaches its finale, the Church of the Unenlightened Light has fully seized control of the Gardens; the staff and residents try to battle them, but to no avail. Loo, briefly brainwashed by Cheeky Monkey cartoons, soon regains consciousness and joins the battle, using her powers to heal the alien that gave the Gardens their magical strengths. The capital-worshippers retreat, and the care facility is restored to its former glory — without Zerc, who dies a slow and agonizing death. Neat closure at last: the healer lives; the selfish man dies.

One does notice that, in that swing of closure, Loo is not wearing her nurse uniform but street clothes, hinting at an impending return to ‘real life’ — a clever choice, extending the story, at least slightly, past the bounds of its pages in the mind of the reader. Yet, at the same time, it feels too easy, as it allows the storytellers to state that Loo has in essence ‘graduated’ from her trauma while relieving themselves of any obligation to show her coping with the life that comes after; even when she has healed, they refuse to imagine her outside of her fantasy world, refuse to imagine her in that real America, the land of mass shootings and soulless capitalism, from which she escaped.

This is what Paranoid Gardens wants its readers to believe: that it is possible to heal oneself through healing others; that care — genuine human care for one’s fellow, for one’s community — can counteract all apathy, all trauma, all moral decay. A romantic sentiment, but nonetheless a defensible one. A shame its creative team could not apply this care to the work itself.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply