Iris Jong is an artist and illustrator based in the Bay area. A true California native, she grew up in Los Angeles and always had artistic inclinations even as a child. Though her portfolio would suggest otherwise, she actually has a daytime job working at a nonprofit that helps adults get their Bachelor’s Degrees and helps them make sure they have the resources they need to get their work done. Though she knows the world of comics quite well, she was one of the cofounders of Comic Arts Los Angeles (CALA) and is passionate about independent comics. Her work is diverse, but she’s driven by the awkward, mundane moments in life that connect us all.

Ingrid Cruz: Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me. I wanted to start out by asking, how did you get started in art?

Iris Jong: I started drawing when I was really young. I think a lot of kids do. You’re just drawing in classes in k-12 elementary school, but also my parents signed me up for some art classes. I started doing things like oil pastel, watercolor, but all of that was very creative in a way but it also involved a lot of looking at masterworks and more classical paintings and then seeing [if you can copy this]. Can you make it look the same as that? I feel like my creative and idea-generating brain didn’t get too much practice. I grew up drawing things like faces, figures, and characters. Fanart was certainly a way that I got through it. In terms of my own ideas and my own original work, I didn’t get into that until my 20s.

In my first year of college, I took a graphic novels class and we would analyze contemporary American comics and also had to make our own comics work at the end of the class. A lot of folks weren’t artists so this idea that you can make comics even if you don’t know how to draw or render was difficult for some. Comics are just images combined with text and thinking about how they interact. But because I had a drawing background, I did an adaptation of an Emily Dickinson poem, actually. The one, “Because I could not stop for death,” and it was really fun. I really enjoyed having something to work off of and, in a way, that’s also fan art. I had an existing work that I was looking at and thinking about how to interpret it visually. I think that was one of the first full comics pieces I created.

After that, I became a little more serious about [my approach]. Can I practice doing zines? Can I practice doing fan comics based on existing novels? Then my friend Angie [Wang] and I and two other folks, Jen Wang and Jake Mumm. founded Comic Arts Los Angeles (CALA). That was one of the first indie comics conventions in Los Angeles. I was involved in that for a few years, met a few more comics artists through that, and since then have been on and off doing more short stories, more essays, and more comics.

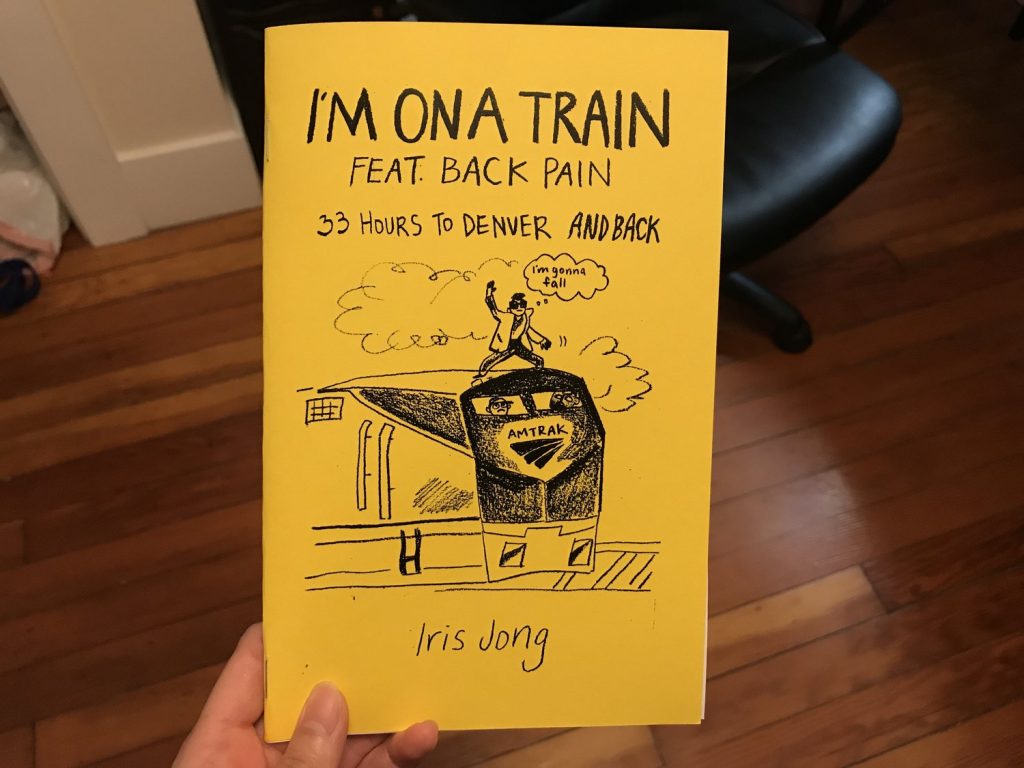

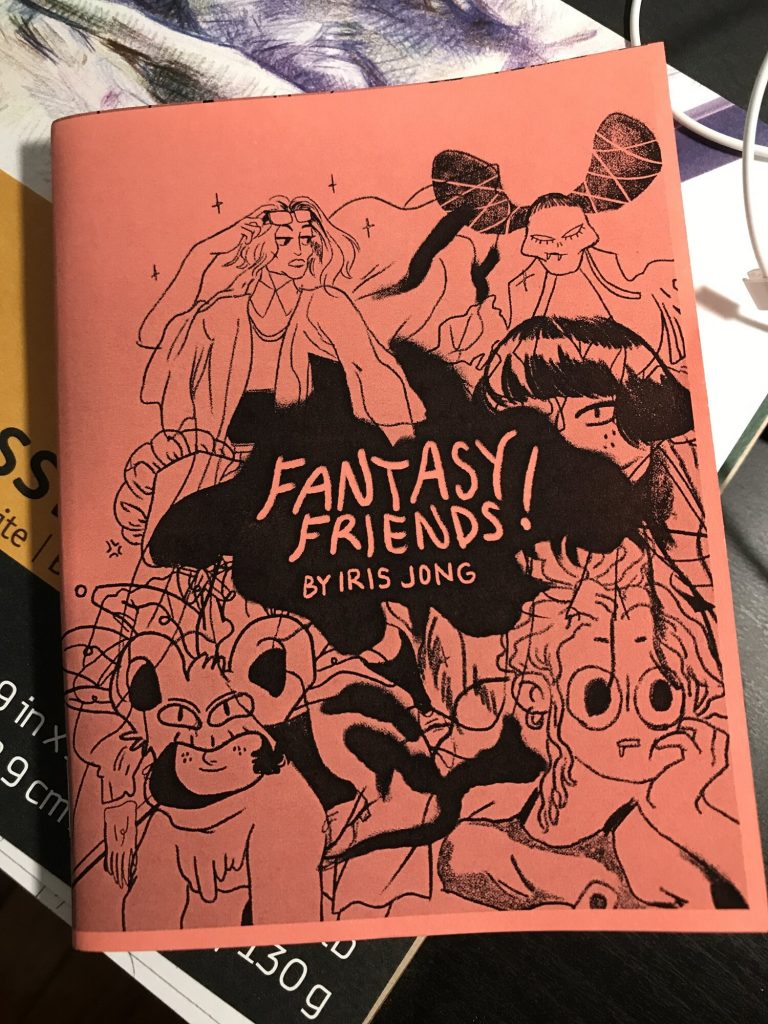

In 2018 I did two zines. One was called “I’m on a train,” it’s a travel zine. The other one was “Fantasy Friends,” which is sort of characters and puns combined together. Those were my first slightly longer zines that had a more focused concept where I was doing that from beginning to end and it’s just my original ideas and trying to translate a concept into a physical object.

Ingrid: I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about your process. How do you come up with a comic idea? Do you sit there and mind map or do ideas just come to you? Can you describe your process a little bit?

Iris: It depends. Usually, I’m a very disciplined person. I really like schedules and hourly goals and knowing, “Monday I’m going to do this. Friday, I’m going to get this done.” That’s all gone away during the pandemic. So I will describe my usual process more.

Because I have a full-time day job, I like to also treat my creative life as something serious and I have quantitative goals around. I typically have drawing or writing goals of 5 to 10 hours a week and just sitting down and focusing on doing something related to my creative practice. Depending on where I am in the process, I might sit down and come up with a list of ideas. More likely, throughout my day, I’ll just be thinking about or observing things that are amusing and putting it all into a Notes doc or Google Doc.

I haven’t figured out the best way to organize those things, but I think by nature they’re creative ideas so they’re not going to fit into a strategy document and I think that’s okay. Usually something rises to the surface as I’m sitting down and, as I think about it, a lot of threads come out.

So like, with my two zines that I did in 2018, they were both humor-oriented and for that [I thought about] what I could get the most jokes out of. In the train trip, as I was just experiencing that I was noting down the things I was hearing, thinking, and [I’d realize], “There’s a dozen different jokes that could come out of this!”

When I sat down a week or two later and looked through my journal and my notes I had, [the jokes] I came up within the moment and the ones that came up as I was sitting down at my desk and made a list. I actually like starting a writing process [by using] a Google Doc where I make an outline of all the jokes. I almost wrote it out. I try to map out all of the pages because you have to publish zines and they have to be a certain page count. I get an idea of how many of the pages I’ve filled, if I have enough content, and if it makes sense as an overall product.

Once I do that, it is [almost] a checklist. I start working from one page and then the next, and then cross them off as I draw them. With the [train] zine I was just doing pencil, so I did rough drafts on a separate paper and, once I figured out the visuals, I drew directly on the final page and that’s what I scanned into InDesign. Once I had all the pages, I would map them out in inDesign and make sure they’re going to print correctly, make sure they’re the right orientation. But once I have that, it’s a PDF booklet. I bring that to the printers, print the title page on a harder cardstock, print the inner pages on usually a plain white. [I] then go through a very manual process of cutting the pages, folding them, [aligning] them correctly, and then I [use] a long stapler [so I can] staple all of the zines myself.

Ingrid: So it’s really a labor of love. All creative work is but hearing this makes me appreciate zines a lot more now. Thank you for describing that to me. If you don’t mind sharing, your website says you’re an illustrator and writer. Is that your day job or do you have another non-creative day job?

Iris: I have a day job that is not technically creative but I get to be creative in it. I work at a small nonprofit. We’re fairly small, about 9 people. I direct the program team so I have gotten to come up with our strategy.

We work with working adults who are trying to earn their bachelor’s degree. So those adults usually have full-time jobs of their own. They often have families and kids. We have partnered with a university that offers an accredited bachelor that can be done online and is self-paced and project-based. Our job as a nonprofit is to coach the students who want to earn this bachelor’s degree and also provide them with financial aid support and community resources. [We] motivate them and make sure they’re managing their time, that they’ll finish the degree quickly. And I get to figure out both how we coach in the most effective way and what academic supports we build. Overall we figure out how students are both committed to school and able to do it and get their degree in a timely way.

Ingrid: That’s really cool. Prior to being a freelance writer I also worked in the nonprofit space and I know that it takes up so much of your time. In nonprofit work, it’s kind of hard to see where it ends and you begin, and then you do this creative thing that requires so much of your energy. The work you do is really great though. I also notice on your website that you have a few PSAs with information for immigrant schoolchildren. I was wondering if this work is part of your commissions or something you did just because. Did you make these for someone or were they projects you made because you care about this community?

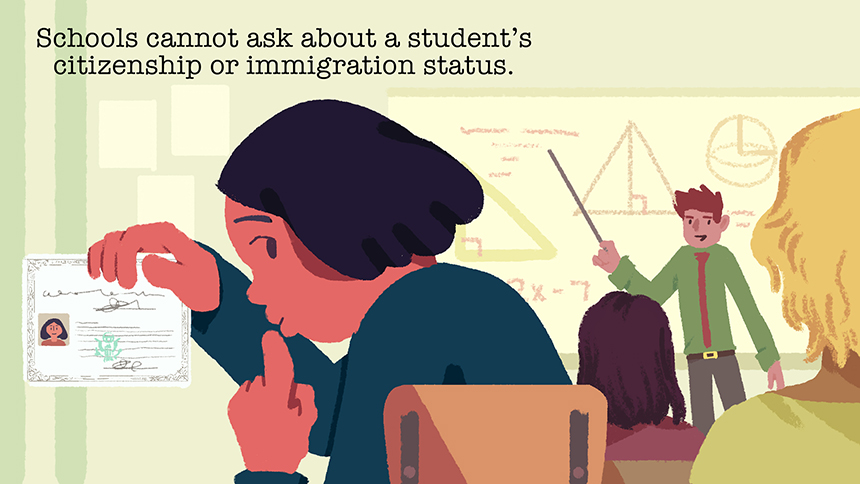

Iris: That was a series commissioned by the ACLU of Northern California. I had a friend that works at an activist organization that does communications and had previously worked at ACLU NorCal. Back then I was more seriously considering if I want to shift from nonprofit work to doing more freelance illustration work. This was one of my first tries [so I could] see how I felt about it. I enjoyed doing them, but I didn’t know how I would feel about doing them full-time. I’m proud of the product and I put some of [the PSAs] on the website as part of my portfolio.

Ingrid: They’re very beautiful and it’s also really great that you do this community work. The next question I have is kind of touchy. For people who are marginalized, there can be a pressure to market yourself based on your background. What has that been like for you as an artist? I feel like your work is pretty universal, yes I see your name and I see that a person of color is doing this work, but there are things about your art that I find relatable. What kind of response have you gotten from more privileged artists and how do you navigate that?

Iris: It’s a really interesting topic because I think it plays into something I continue to question and don’t have an answer for at all. Like my social media presence, what would it look like to really try to gain an audience? What I’ve done in the past is mostly [try to gain an audience] through my personal networks and through these mostly in-person zine events and comics festivals. You might have noticed I don’t have much of a following and I haven’t tried too hard to get one. I think it’s part of what you reference, which is… social media is designed so that the more specific, and niche, and clear you are about who you are, and the clearer you frame yourself and your identity, the more easily people can find you because that means your brand is very clear and concrete.

I think especially as someone who does a variety of kinds of genres and art, I just haven’t figured out what I’m willing to do or where I would land on the spectrum of being very specific vs. doing what I really want, which is broad and changes every month and doesn’t necessarily cue to one identity. I’m also queer and [asexual].

Ingrid: When I looked at your work, I was surprised because people who make art like yours usually have a huge following. But it’s a difficult path when you have so many facets to yourself and there are so many preconceived notions that, unfortunately, other people project onto an artist. I notice that with marginalized artists there’s also an expectation of the type of art they should make.

You also work at a nonprofit and a lot of times in that nonprofit space, community organizers may decide to consume only art that is social justice-oriented. I used to be that way as well, but now I want a break. I want to laugh at something and not talk about my trauma all the time. I kind of see a little of that in your work as well. You deal with so much, and yet you have this sense of humor that I really appreciate. I also noticed that you write essays and you wrote something that really appealed to me. You talked about the importance of the mundane, and I see that in the zines you wrote. I was wondering what made you focus on those details. When do you find that moment?

Iris: I definitely consider the mundane or even the domestic as one of the themes I’ve been most interested in, especially when it’s [up] against a lot of power or grandiosity. I think it does tie to my identities. I think that’s really important with queerness. And, also, I’ve had mental health issues. Depression makes you think life isn’t worth it and it makes you ignore the mundane in life and think that small moments don’t matter.

I think part of why that theme is interesting to me is that it’s really forcefully saying, “No, the mundane is what life is.” That is where every life and every person is different. It’s kind of marvelous that every person gets to experience the mundane no matter who you are, what your position is, or what stage you are in life.

No matter how much power you have, you’re going to experience mundane moments, and they’re going to be slightly different from each other, but they’re also going to be universal in a way because we all get up and eat breakfast. We are all annoyed when we stub your toe against the table. These things happen to most everyone. I think there’s wrestling with what is universal but also what is overlooked, and those moments are also often very funny. I like playing with those scenes for that reason.

Ingrid: That’s awesome! I definitely agree with that. I don’t know if you pay attention to photographers, but what you said reminds me of two of my favorite photographers: Stephen Shore and William Eggleston. I actually hated them when I first heard of them. Now that I’m older, I appreciate the mundaneness of life. They took pictures of an egg, or whatever. I didn’t get it. Then I went backpacking in Perú and realized I was the only person of color in my hostel sometimes. People kept thinking that I worked there. I would try to drink my coffee or watch Netflix on my laptop and travelers kept interrupting me. Then I got it: that’s white privilege, they get to look at the egg and don’t have to think about anything else. I realized these mundane moments are important. Your work makes me think of those things; even though they’re photographers, I feel like there’s a common thread in your work and theirs. But I digress. I wanted to know a little bit about Comic Arts Los Angeles. Can you tell me how you decided to start that? I was wondering what kind of environment you were going for and how do you think CALA helped local artists in L.A?

Iris: It was incredibly random the first year. It was 2013 and Angie [Wang, also an illustrator and comic artist] and I were talking about how many cons exist on the East Coast, especially indie festivals. Offhand I asked, “Why don’t we have one here?” and Angie was like, “I don’t know!” and ended up texting her friend Jen Huang, who is also a comics artist. She asked [Jen] “Do you think we could start a comics festival in L.A.?” Jen talked to Jake, who is her partner, she said we could probably do it even though we had no experience putting on an event like that.

It turned out we happened to have the right set of skills and temperaments to make it happen, and it was so fluid. Jen and Jake went and looked for partnerships and spaces. Angie did a lot of advertising on social media for the event and got a lot of really prestigious and accomplished artists to come. I had my nonprofit and strategy skills, so I put together spreadsheets and did a lot of the backend documentation and organization, and we pulled it off that first year. It’s been really strong each subsequent year.

Out of the comics fests I’ve gone to, it has a very intimate [ambiance] and it feels like high quality, but really varied in the kinds of styles of artists who exhibit. I think the audience is also similarly varied. They’re diverse in age, race, sexuality, gender…all of those things. Over the years, we’ve had more of a focus around the community aspect. So I know Angie, Jen, and Jake started to do a comics drive to donate comic books [and] there’s more outreach to libraries. It’s evolved into more of a community event while also keeping that focus on independent comics.

Ingrid: You mentioned that you’re mostly consuming other people’s work so I wanted to know what inspires you?

Iris: These days, a lot of comedy and also queer fiction. I’ve been looking at more front-facing camera comedians. Eva Victor is one, she did “The Portrait of a Lady on Fire.” That just really tickled me. I feel like a lot of the comedians who are becoming viral and popular in that space are female queer POC. So I think there’s something about the form. It almost reminds me of comics. It’s not [comics], but it has a similar thinking about panels, dialog, and expression. I’ve been really drawn to that. [I’ve also been reading] comedic manga, so Gekkan Shoujo Nozaki-kun is one that’s been around for a while and has both an anime series and a manga series. I grew up with a lot of the humor in manga, and it really makes me happy and appeals to me. Alex Norris does the “Oh no” comics. They are a queer trans artist and has an exquisite sense of humor. Various books, like Band Sinister by KJ Charles. It is queer and poly and that was a delightful time as well.

Ingrid: I think a lot of people are intimidated if they’re first time artists trying to get into the world of comics and zines. What advice do you have for people who are new at this? I feel like people, especially women, are socialized to think that this is a boy thing.

Iris: I think that [like] the way people think of animation, they immediately think it’s a kid’s genre, or that’s Pixar. Comics is a medium, not a genre. Comics are a vehicle for expressing what you as an artist want to express, and it can be extremely simple because at its basic roots it’s just combining image with text. You can just write a poem and then draw some images around that and you can argue that that is a form of comics. Think about what you feel comfortable doing, whether that’s doodling or writing little bits. [You may even] text your friends funny lines sometimes. Start there and think about how to add art to it to make a comic. Maybe don’t start with mainstream comics as what you are trying to imitate. There are plenty of indie comics that are really excellent and you can start with the Comic Arts LA page and see who exhibited, what they worked on recently, and then starting with that as your basis for inspiration.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply