I had an immediate negative reaction upon cracking open Jack Cole’s Betsy and Me (Fantagraphics, 2007). Cole, after all, was one of the most exuberant cartoonists not just of his generation but of any generation. Whether it was his creative comedic chops on Plastic Man (a character constantly recycled by different superhero creators even though only Kyle Baker seemed somewhat able to grab ahold of him). or his over-the-top curvy ladies for Playboy, Cole’s signature was not just doing things well but overdoing them. He was an able draftsman, but he did not let that talent limit him in the bounds of realism. His style was his own. Oft referenced, never equaled (Even Baker, as fine as a comedic artist as any you might find in the 21st century, chose to focus more on character comedy and media satire than trying to compete with Cole’s rubbery charms).

Yet there he was in this volume, tinier in both size and content, obviously playing according to someone else’s tune: the figures and overall design sense in Betsy and Me seem obviously influenced by the minimalist approach of UPA – all simple geometric shapes and modernist design. It seems not just un-Cole but almost anti-Cole, the furthest thing you would expect him to do. A gentle family comedy, with just enough barbs to make one chuckle but not enough to seriously offend the reading public (Some of his 1940’s work in would, in its approach to law and order, would appear more radical).

Which makes sense. Betsy and Me appeared not in the high-paying-but-scandalous Playboy or in the low-paying-and-no-one-cares comic books; no, it was in the holy grail every cartoonist aspired to – a syndicated newspaper strip. After years of being read by either the lecherous or childish, Cole would have the chance to be read by everyone, which meant smoothing down the edges. Of course, Cole didn’t live long enough to see if the strip could make him into the next Charles Schulz, he committed suicide barely three months into its run; a few failed attempts at continuation stalled and strip was mostly shoved into memory with dozens and hundreds stillborn newspaper strips (Three months is nothing in the world of syndicated strips, to keep the Peanuts comparison going – the first three months of Peanuts are nearly unrecognizable to the modern reader; it took Schulz years of work to get to the ‘classic’ set-up and familiar designs. In fact, Betsy and Me begins with the set-up of the two parents and their five-year-old child already living in what we can assume to be suburbia before immediately going into a long flashback showing the couple meeting, marrying, raising the baby etc. When Cole died they just barely moved into what is meant to be the status-quo setting for the strip).

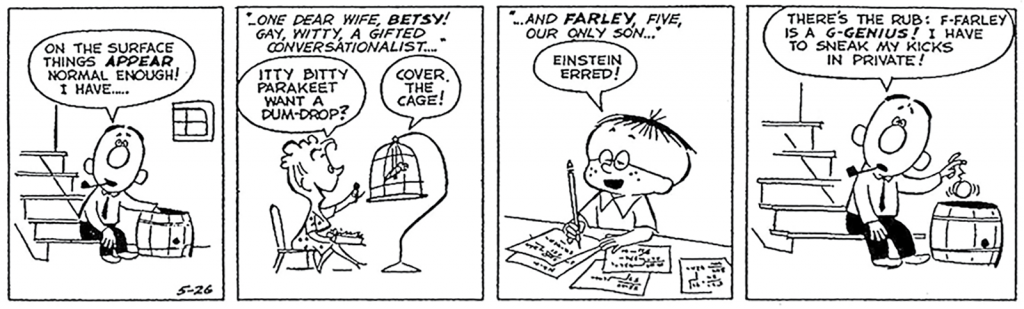

So I opened the book ready to be disappointed… only to find myself in the pro-camp by the end. Granted, this isn’t a hidden masterpiece, and far away from being Cole’s first, second, or even third best work; but the man proved able to work within the new mode of expression, limiting as it was. It helps that while all the characters are familiar, the dopy husband, the overtly brilliant child, the status-seeking wife, they are never flattened into the realm of pure caricature. The story always treats them with sympathy, without glossing over their foibles. Thus the protagonist, Chester B. Tibbit, often daydreams and fails to comprehend reality correctly, but his heart tends to be in the right place; and he is the only one to suffer for his sins (well ,his boss seems to have blood-pressure problems because of Tibbit’s flightiness… but no one should have any sympathy for that guy).

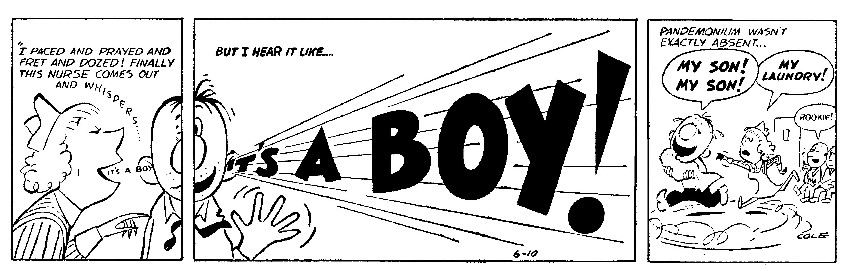

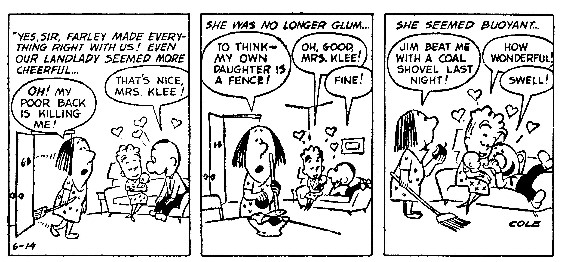

Cole’s smart storytelling choice is to position the strip directly from Tibbit’s POV – we don’t see it from an omniscient angle, like most of the competitive strips, but rather hear his thoughts as they accompany the images. Most of the comedy comes from him misunderstanding an issue and failing to even notice it. Tibbit tells the story like most people do, as if he’s the protagonist, but the readers can see him for the clown that he is. This trick also allows Cole a few touches of visual brilliance in the otherwise unyielding format – in the June 10 strip, Tibbit hears that he has a boy; the nurse whispering, but to his subjective view at as if she’s crowing the news for all the world to see. The words literally crowd out the panel, so much so that the usual four panel structure is now only three. That’s a good enough gag by itself, but Cole caps it up by taking things another notch: so overjoyed Tibbit that he runs around shouting “my son! My son!” while behind him an angry woman shouts “my laundry!”

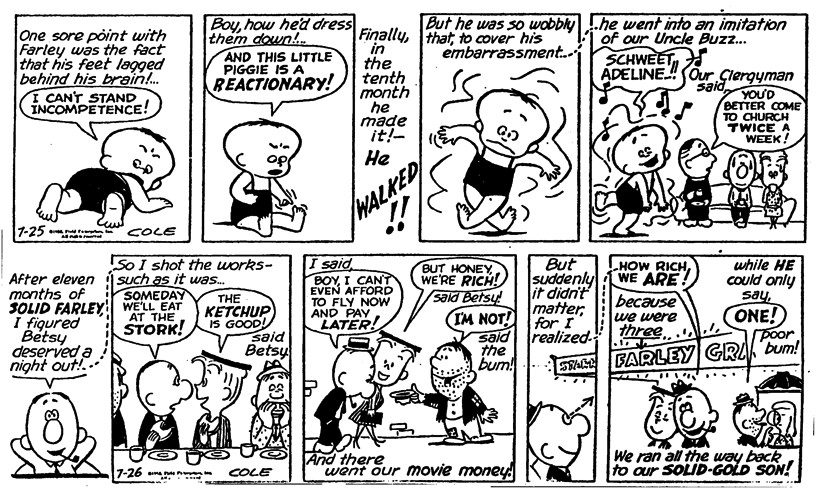

None of this is particularly revelatory, but it is done with quiet self-assuredness that propels the story forward. It is only towards the strip’s (premature) end that the art and story start to truly mash together. As Tibbit and Betsy grow from the joys of childbirth into the humdrum of modern living as white people in 1950’s America, suddenly the whole thing takes a sharp turn. Tibbit loves his son but admits he cannot relate to him, in fact, all other adults are quite put to shame by child’s intellectual bent, pretending to engage in important conversation when he’s around.

More than their child, the couple’s biggest problem is their environment; though suffering from what we might call ‘The Simpsons Problem,’ in which older generation’s description low-middle-class existence appears highly aspirational to current readers (Which is probably part of the reason the show slowly left behind the poverty gags long ago): Tibbit and Betsy are able to afford rent even though only Chester works; and as a lowly floor-walker in a store. Still, in their own eyes, the Tibbits’ are awfully poor (the limited POV style works best here because it seems like their neighbors are looking down at them, but its always what Tibbit feels – there’s a level of social paranoia at play). As the strip progresses they find themselves forced, or imagine themselves forced, to buy a car (which brings them more trouble than joy); and later still to buy a house in the suburbs.

Suburbia jokes are a dime-a-dozen these days and I imagine not that novel even back then. Still, it is genuinely funny to see Cole depicting the lost patriarch failing to find his home amongst the hundreds of constructed clones. The ‘modern’ aspect of the UPA style is in full force here, the older Cole was too ornate in his style to simply draw the same house over and over again.

By simplifying, Cole allows himself to draw a simplified reality. One in which people can only be coerced to pretend intellectual pursuits are worthwhile by the presence of an impossibly smart five-year-old (it’s not a very good gag, but it sets the direction well, the very first strip shows Chester mentioning how smart his kid is and then reveals that he, the adult, plays with a yoyo – “I have to sneak my kicks in private.” The life has the outside façade of sophistication, middle-class and middle-brow, but beneath there is little). The life is as shallow as the depth of the cartooning style – 2D reality for 2D people. Farley upends their ordered reality by being a born outsider. His father loves him, but cannot understand him. The only other character that can converse with Farley, if not on quite on an equal level, is the family’s lecherous friend – another outsider figure marked by his insistence on avoiding the 2.4 children lifestyle.

There’s enough in the strip as is to make it a worthwhile read, and worthwhile to analyze, and yet all that thematic content is pushed aside by its place as Cole’s final statement. The book opens with a long essay by R.C. Harvey, which joins the analysis by Art Spiegleman’s Jack Cole and Plastic Man and Ron Goulart’s Focus on Jack Cole, all of which engage with the work as sort of a key to the riddle of Cloe’s suicide. Harvey writes: “If the evidence of Cole’s published work suggests tension in his marriage, Betsy and Me may reveal why that became, at least, unbearable.” Spigelman also believed the strip was doomed from the get-go, a sign that Cole renounced the free-expression of his early comics work in favor of the choking prison of respectability / newspaper strip / suburban life.

There’s something alluring about this reading of the work, and the man who made it. It offers a neat summation that ties the two as one. Cole is the work and the work is Cole, wholly and utterly. I almost wish I could read the work again, without knowing – would the fact the strip seems to be rushing through stories that other strips would drag for years still jump at me? Comedic strips of that type would usually pick a slower approach, and if they find a decent avenue for gags they would squeeze it dry over weeks and months. And yet in Betsy and Me, the couple’s financial woes in trying to find a new house are solved in a couple of short strips. Before you know it they have achieved everything they claim they want to. It’s as if Cole was rushing to the status quo he established in the first strip only to realize he had nowhere to go.

Obviously, comics strip in particular are very good at going nowhere. No one reads Nancy expecting her to mature into adulthood. The exceptions, such as Gasoline Alley, are well… exceptional. Betsy and Me didn’t seem to aim for exceptionalism, though playing such a game of historical ‘what if’ is even more useless than trying to summarize what went in Jack Cole’s mind based on a couple of strips he could’ve completed weeks before.

Are there any hints of couple troubles in Betsy and Me? Not in what I saw on the page in the first read-through; if anything the couple is almost blissfully happy. Their problems are with their son and social circle, not with each other. You could make the point that Chester’s POV simply glosses over the problems, that the happiness is just another aspect of the façade. But this is a subtlety of storytelling rare in Cole’s work, and the whole of the joke in the strip is that we can see, quite clearly, where Chester and reality depart. Unreliable narrator aside, this isn’t trying for Lolita.

And yet, once I knew the facts in the case of Mr. Cole, I couldn’t put them out of my mind. The whole of the strip, already painted with slightly sinister shades, became almost entirely grim. The smiling Chester is moving from one day to another, getting closer and closer to his doom (the end of the strip); a quiet and undignified end shared by many (other comic strips that is). Talk of separating ‘art’ from the ‘artist’ has become common these days, usually in regard to artists whose (negative) deeds overshadow their work.

Betsy and Me shows a completely different version of this question. As far as I know, no one ever charged Cole with anything (well, there are some pretty racist comics he drew during the Plastic Man period….), can we read the work without reading the artist’s life into it? Especially when the work is tied, chronologically, to his suicide? Harvey and Spiegelman certainly think we cannot. Betsy and Me as it currently stands, the collected version (the only one people are likely to read today), stands not just as a book but as a monument – a headstone.

Which is quite a lot of burden to put on a cute little book of mostly gags. It feels unfair to the work, which shows some of the old brilliance that Cole always possessed. To narrow it all to the point of personal tragedy, a reflection of the artist in his darkest moment, is, to me, to miss the forest for trees. Jack Cole committed suicide, but that’s not the only thing he did and that’s not the sole measure of his life. He left behind him an impressive amount of impressive work (sadly, so much of it is out of print). Betsy and Me is funny, and charming, and surprisingly sharp (occasionally). I don’t know if we should separate the art from the artist… but, in this case, at least, we should probably give it a shot.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply