Having known Eric Reynolds for a long time and understanding his tastes, as well as reading the anthologies he’s edited, it’s obvious that he has a strong predilection toward comics that are absurd and grotesque. However, he also clearly has a great deal of appreciation for rock-solid storytelling and fairly traditional cartooning styles, if not content. You’re not generally going to see a lot of abstract comics, comics-as-poetry, or even immersive & murky art styles in one of his anthologies. There are exceptions, but one must bear in mind he’s balancing his personal tastes with what he thinks an audience will sell. That said, Reynolds grew up as a fan of Chester Brown and Yummy Fur, and “Ed The Happy Clown” in particular. Every time I read something that Reynolds has edited, I think of this classic comic as a frame of reference. It is weird and disturbing but also hilarious and transgressive in unusual ways. It’s unpredictable and incorporates genre elements in surprising ways.

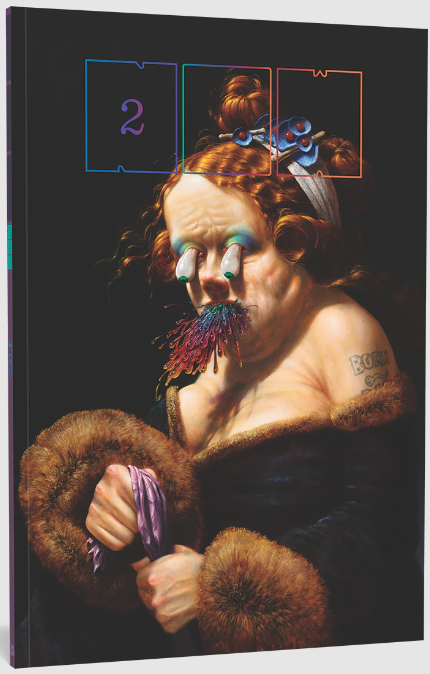

After lining up a slightly more familiar and popular group of cartoonists for NOW #1, Reynolds really lets his freak flag fly in some interesting ways in NOW #2. The painted cover by Christian Rex Van Minnen is truly a statement of purpose: an oil painting done in an entirely naturalistic style with ridiculous, grotesque elements like the model’s eyes literally popping out and multi-colored effluvium flying out of her mouth. It’s like a parody of portraits by the Old Masters, a thumb in the eye to Fine Art.

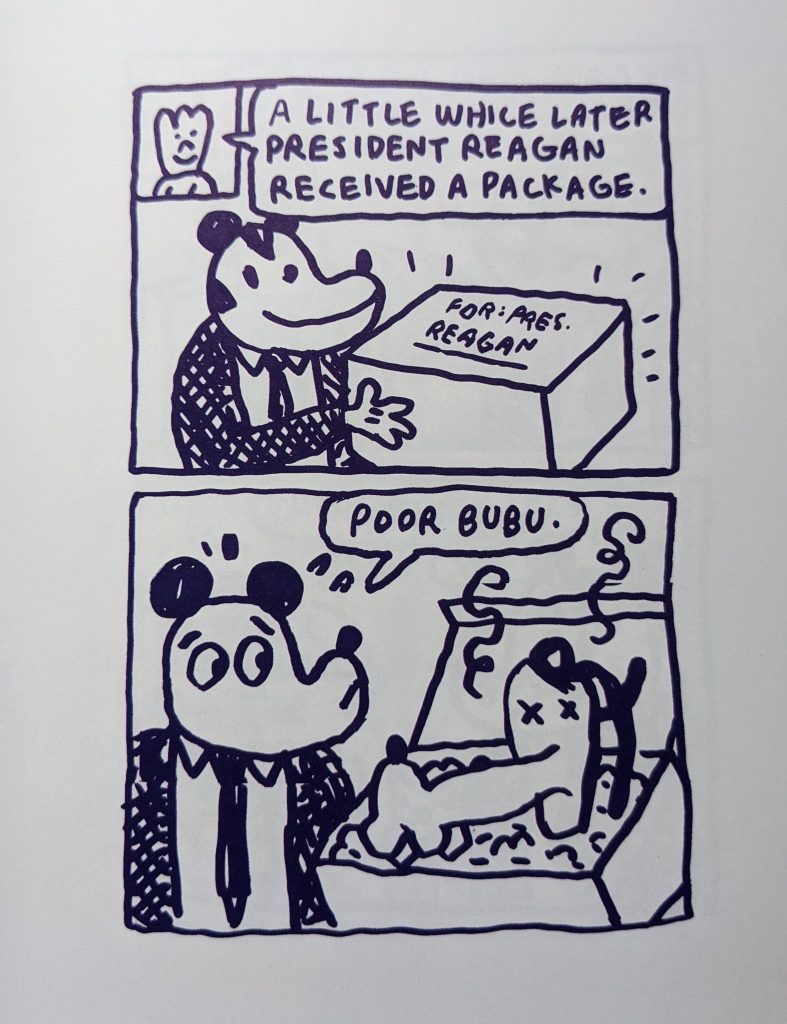

The opening anchor piece, “The Apocalypse According To Dr. Zeug,” was originally published as a series of minis by a Brazilian cartoonist named Fabio Zimbres, and reprinted here in English for the first time. Initially published in 1997, Zimbres evokes Gary Panter in terms of style. There’s a crude immediacy in his line that energizes this story about a story wherein a weatherman prophesizes the world’s end, thanks to greed and a desire to be controlled. Peace will reign thanks to a Leviathan-style figure who imposes order. It’s no surprise that he advises Ronald Reagan on how to control things, given the deep hatred of Reagan in Central and South America. The story is bookended by another character who is given three wishes by a genie; after wishing for money and women, he also wishes for wisdom–but leaves it unopened. Not much about this story is subtle, nor is it meant to be. It’s a howl, it’s a scrawled form of desperate resistance.

That apocalypse is followed by Tommi Musturi’s “Samuel,” a silent story where its characters bust through a brick wall, escaping their own apocalypse and returning to nature. The almost lurid use of color enhances the cartoony ovular character design, creating an atmosphere that is at once familiar and resolutely artificial and non-naturalistic. Whether or not this escape to the forest and ultimately the ocean will result in a thriving community or just a temporary respite is left deliberately vague.

The next three stories form a suite of connected ideas, as they are all various slices of life of individual, iconoclastic characters. Josh Cotter’s “Illustrated Excerpts From The Diary of Dr. Charles D. Humberd” is about a doctor who wrote case studies about gigantism, but his diaries (from medical school, it would seem) veer from utterly emotionless banalities (what he bought and ate, and how much everything cost) to overwrought (but still emotionally flat) diatribes about a woman in his life making fun of him. After that outburst, things return to normal. There’s a dense dustiness to Cotter’s art, which looks like it was shot straight from his highly detailed pencils. Humberd’s grim and somewhat flat demeanor never changes, whether he’s eating or dissecting a corpse. Given that he was later sued for treating a man with a case of gigantism like a medical freak instead of a person, none of this is any surprise.

Sammy Harkham checks in with another tale of Hollywood, this time on the set of 1949’s The Heiress. A classic film, star Olivia de Havilland won her second Oscar for it. With a pleasant light green wash, this single-page strip acted as a palate cleanser between two dense, pencil-heavy comics. There are a lot of good jokes here, as the famously ill-tempered de Havilland had to deal with young Montgomery Clift fumbling his way through one of his first major roles, a demanding director in William Wyler, an eccentric Ralph Richardson playing her father, and her constant antipathy toward her younger sister, Joan Fontaine. This was a little delight in what is clearly an ongoing series for Harkham, done in his elegantly expressive clear line.

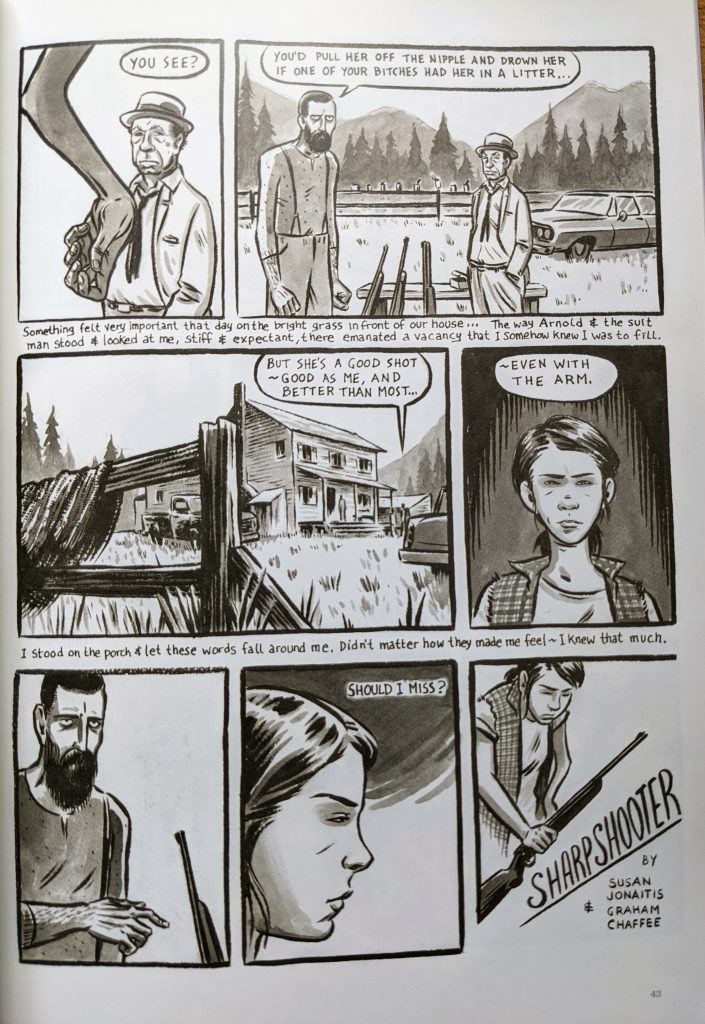

Harkham’s piece served as the palate cleanser for another densely penciled piece: Susan Jonaitis and Graham Chaffee’s “Sharpshooter.” It’s the story of a fictional carny sharpshooter named “Powderkeg Peg”; but, in particular, it’s about her transition from growing up in an abusive household and essentially being sold to the circus as a performer. Peg’s withered arm was a point of shame and abuse until she met Sophie, a fortune-teller with a scarred face. It was a moment of seeing and being seen and understood, as well as an introduction to a found family. Each of the three stories in this section dealt with the quotidian details of performers and authority figures at various stages of their careers; each had to deal with their own set of frustrations.

The next four stories form a suite of their own, one marked by highly stylized lines and vivid uses of color. Conxita Herrero’s “Hot Heavy Days” humorously incorporates visual cartooning tropes into the narrative, as some lazy thought balloon trails suddenly become physical objects that trail around the protagonist. She has no clue as to what they are, even as the reader initially sees them as part of a familiar cartoon language before they intruded on her reality. Ariel López V.’s “A Perfect Triangle” similarly uses highly cartoony character design and bright (bordering on psychedelic) colors as a woman and her ex-boyfriend explore a mysterious series of triangle symbols on houses all over town. Told from the point of view of the ex-boyfriend, the way that it mixes slice-of-life tropes with a truly over-the-top ending cleverly twists reader expectations. All along, he keeps imagining various kinds of absurd conspiracy theories, aliens, Satanists, etc., even as he figures this is her way of wanting to hang out with him again. By undermining the mystery until the stunning climax, López only serves to heighten it.

Dash Shaw’s “Ford” is one of his short pieces that experiments with color in non-narrative terms. Or rather, color is used to advance the emotional narrative of this story about a man without a car trying to get a date. Shaw captures, without text, just how horribly the man acts after they hook up, in a way that conveys that he doesn’t even understand how what he says is harmful. She is clearly on her way to wanting to turn their encounter into a relationship and pours her heart out about being a recovering alcoholic after she crashed her car. He makes a flippant remark about how if there was public transportation, she could drink all night. Shaw uses a silent panel to express not just how hurt she is, but how stunned she is that he would even say that. The bruised colors surrounding her and floating throughout their conversation add to this effect.

Anuj Strestha’s “National Bird” caps this portion of the anthology, as birds with cameras instead of their normal heads fly around a city at night, silently documenting what should otherwise be private moments of human existence. The blue-gray wash not only serves to help depict nighttime, it is also reminiscent of a computer screen. The naturalistic, clear line differentiates it from the prior three pieces, but the subject matter and technique touch on them at the same time. It also serves as a transition to the final piece, the back anchor of NOW #2.

That would be James Turek’s comics poem “Saved,” a long take on familiar Western shoot-out tropes. This is an interesting piece that doesn’t quite come together, as the text feels too disconnected from the absurd cartoon shenanigans occurring on the page. The anthropomorphic lizards and frogs, the shootout ending in an armadillo stampede, and other absurd elements simply don’t mesh with the dry, dirge-like quality of the text. It is still well-positioned as a piece that consciously and openly draws on its cartoony elements, fitting in with several other stories in this volume, but it doesn’t work as an anchor piece.

Joseph Remnant’s “Photo Case” serves as the outro piece, a one-page strip about him finding a set of stunning, haunting photographs at a yard sale, along with a set of diary entries from the photographer. She wrote of being visited by God, who told her never to share the photos; in the story, Remnant feels compelled to destroy them. It is a fitting end for NOW #2: an anthology full of secrets, mysteries, otherworldly interventions, grotesqueries, and utter absurdity. Like a curiosity shop or trunk of curios found in a dusty attic, not everything fit together snugly. Though lacking the kind of stand-out pieces from the first issue, NOW #2 feels greater than the sum of its parts.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply