CW: This review will discuss themes of child neglect and death.

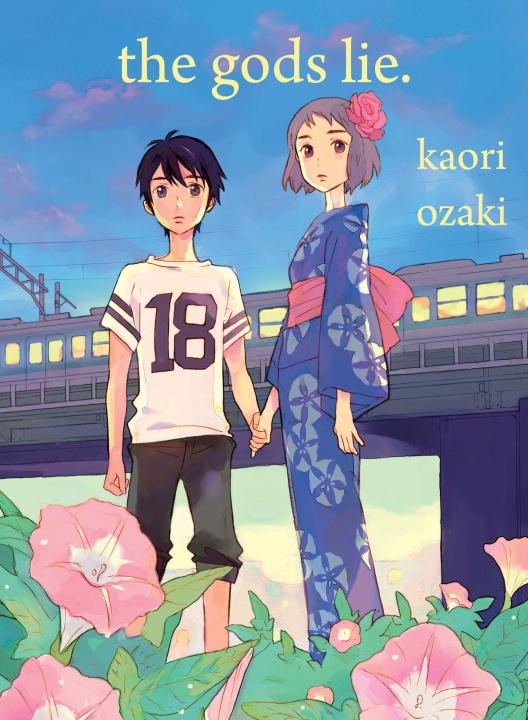

Published in 2016, the gods lie is a brilliant self-contained single volume of manga with a powerful story about the complexities of childhood and the death of innocence. In it, soccer-loving sixth-grader Natsuru Nanao happens to strike up an unlikely friendship with the reserved and often whispered about Rio Suzumura. Natsuru is happy-go-lucky, living much without a care, until one fateful summer where he skips out on soccer camp and learns more about Rio and a dark secret that threatens everything.

Kaori Ozaki, also the creator of other series that center on young adults, such as the more recent The Golden Sheep and Immortal Rain which introduced Western audiences to her work when Tokyo Pop was flying high in the early 2000s, created something really special here with this manga. Ozaki’s work in this single volume features a narrative that speaks to the parentification, the need for support systems, and the toil of emotional labor that is often placed on girl children in families that is not always found in literature, much less comics.

The major spoiler in the gods lie is that Natsuru stumbles upon Rio Suzumura’s secret: she and her young brother have been abandoned by their no-good father, and their only living relative, their elderly grandfather who lived with them, has passed away unexpectedly at home. With a mother that left years before, the reserved — and often whispered about — Rio Suzumura took it upon herself to bury her grandfather in the garden, all to keep up appearances. She does so with the fear that, if she doesn’t, she and her brother will be taken in by child protective services and separated from one another, which means that the only home she’s known, her grandfather’s house, will be gone. It is a terrible weight for an eleven-year-old to carry, one she hasn’t had the time to fully process, as evidenced through the several events by which she’s moved to tears throughout the book.

Grown-ups Are Flawed

Rio’s situation is a terrible one, yet it is one that is more common than we may think. When Natsuru first asks about the whereabouts of Rio’s father, she tells him that her father is a fisherman and he’s gone for long stretches of time but sends money home. Later, near the end of the manga, it is revealed that Rio’s father is actually still in the local area. Going fishing in Alaska for crab was just an excuse: especially since he’s just been boozing it up at the nearby bars and intentionally ignoring this family. This is even more evident in the last pages of the manga when he’s arrested by the proper authorities.

Rio’s father was selfishly thinking of just himself. His excuse? He was “sick of living at home”. Placing himself before his family certainly made things worse and increased the strain on his oldest child. Consequently, this leads to the parentification of Rio. Parentification is “a form of emotional abuse or neglect where a child becomes the caregiver to their parent or sibling” as defined here by Jennifer A. Engelhardt in an academic paper titled The Developmental Implications of Parentification: Effects on Childhood Attachment. The one who has caused the harm here is Rio’s father, yet so much of the blame lands on Rio, the sixth-grade girl who buried her grandfather by herself and kept her family going.

Thinking back to the title of the work: the gods lie, If we substitute “gods” for “adults”, we can link this to the manga’s narrative of children finding out that adults truly are not without flaws. Adults make mistakes that often cause great strife in their everyday lives, upheaving everything familiar for the children in their care. Children often have to pick up the slack of the failings of their parents. Poor Rio was doing everything she could to keep the world’s prying eyes off her father — as a way to try and protect him. The truth of the matter, though, is it really was she who should have been protected and cared for.

As shown in a flashback in the later half of the manga, Rio’s father abandoned his family under the guise of going away on work trips to earn money for the family. In the scene where he announces his plans of “work” and asks Rio to keep it together– to run the household — she grumbles that she does most of the work anyway. This gives us insight that he, as an adult, hasn’t done a very good job of handling their home and allowing his daughter a safe place to grow up and thrive. When the truth of her abandonment and his daughter’s impromptu burial of her grandfather is revealed, children at school and adults in the neighborhood alike treat Rio poorly. Very little sympathy or compassion is shown for this child who simply tried to make the best of the situation she found herself in.

With already so much on her shoulders, she’s made out to be a social pariah with no one on her side acting as a support system minus Natsuru. And he, as a child himself, doesn’t have much standing or power to where he could protect her in a way an adult could. Rio’s situation relates to this concept of parentification by the unlevel ground her father has placed her in, making her make decisions she, at her age, should not have to, possibly traumatizing her with actions she’s made. She’s also had to take on more and more responsibilities as time went on that seem minor (grocery shopping, laundry), but add up with the other overwhelming tasks she’s picked up (keeping lights off to keep utility bills down and keeping away nosy neighbors who would discover their secret).

Ozaki, here, wants readers to ponder on just how affected children, still developing, can be when they find themselves in unique situations where they are forced to do more than worry about simple childhood concerns like school lessons and soccer games. To that point, in this work, she’s exploring how little girls can pick up the worst of this and how gendered society can be in what is expected of them– how they can be thrown under the bus for circumstances beyond their control.

Gendered Responsibilities In The Family

It’s not uncommon to see children and young adults in manga and anime picking up the slack in place of their parents. Often, children in these mediums add more responsibilities to their day in order to take care of themselves, younger siblings, or a parent in need of assistance. While emotional labor is certainly a phrase that is making rounds in conversations much more often nowadays, it is nearly most used exclusively when speaking of gender and work. Wives and mothers often handle most, if not all, of all the invisible work in relationships and this is what has been categorized as emotional labor. In her piece titled, The Concept Creep of ‘Emotional Labor’ for The Atlantic, Julie Beck writes that the term “emotional labor” was first coined by the sociologist Arlie Hochschild in her 1983 book, The Managed Heart.

Hochschild originally conceived Emotional labor as referring to the work of managing one’s own emotions required by certain professions. The term was applied to many female-led professions, such as flight attendants or, perhaps, even school teachers. According to Hochschild, the original meaning has been expanded on and extended into a definition that fits a more modern feminsit utility in today’s world. This comic by French comic artist Emma illustrates how the term has been used in modern day families regarding gender roles. In this comic, Emma demonstrates how girls and women are socialized to multitask and handle managing more and more of the household that often translates to the “invisible work’.

This “invisible work” includes not just household chores or childcare, but also remembering and being on top of being responsible for everyone else’s happiness and acceptance: buying a thank you card for a gift received by another family member, making doctor appointments, and so on. Further examples of emotional labor and this “invisible work” can be found in narratives across all genres and demographics. For example, looking at shojo manga, there is the teenaged character Tohru from the fan favorite series Fruits Basket. Tohru handles the cooking and cleaning in the Sohma household, primarily because she did most of it when her single-parent mom, Kikyo, was alive and found herself good at it. While I will note that she does this to initially barter in place of playing rent with the Sohmas, all the work falls to her in this new place as the three men she ends up living with are woefully unequipped to cook and clean after themselves.

Alternatively, there is the character from Horimiya, Hori, a popular high school student who excels in her studies. She has to look after her younger brother and do the housework, leaving her no chance to socialize outside of school. With both her parents often away from home due to work, she has her life full of the “invisible work” and her peers from school always question why she is so elusive. Hina, from Makoto Shinkai’s Weathering With You, is caught in a situation similar to Rio from the gods lie: she’s the sole caregiver and supporter for an eldery grandparent and younger, male sibling. As the pseudo parent or mother, it is up to Hina to make sure her brother gets fed, clothed, and is safe from adults who would separate them if they find out what their situation truly is.

Because that’s a central theme, most of Weathering With You’s narrative follows Hina’s special ability to make do with her circumstances and how much she has to give up in order to make that a reality. While the film heavily features fantasy elements, it’s a terrific commentary on female children and emotional labor, especially within their own families. Hina deserved a better support system as Rio does in the gods lie. Rio is a child who goes without much: a responsible parent who put the world on her shoulders and burdened her by not stepping up. Here in the gods lie, Ozaki is reminding us just how little agency children have in the world when compared to adults with a special lens focusing on gender with Rio at the helm.

One could argue that her elderly grandfather, when alive, could have served as a support system for Rio temporarily–yet he was mostly dependent on her for food and care. Where Natsuru has an overworked but present mother in his life, a soccer team of boys his age, and an aging coach who has to quit because of health reasons, he is still better off than Rio. Outside of her family, Rio had no one, no friends at school or in the neighborhood she could confide in. No relationship with a favorite teacher or grownup at school or in the community.

The Emotional Toil and Consequences

Despite being a young girl, Rio has to grow up faster than most if not all the kids her age and in her grade. It’s important to note that because Rio’s mother left even before her grandfather’s untimely death and her father’s abandonment, it is hinted that she had taken on such tasks already like cooking meals. The manga doesn’t give any more details about the mother and her leaving but, with how flaky the father turned out to be, it is not a stretch to assume that Rio had taken on more responsibilities as a child after her mother’s departure. Rio more than likely had to fill in her shoes, no matter how absurd that thought is. For example, in a flashback, at dinner with her then alive grandfather, kid brother, and father who complains about the imitation crab and vocalizes his desire for real crab, Rio shuts him down saying that they, as a family, can’t afford it. The tone of the scene doesn’t strike me as a funny moment between the family at dinner but, instead, serves as an eye-opening moment in their household of the father and his inability to read the room and take stock of their situation and take action.

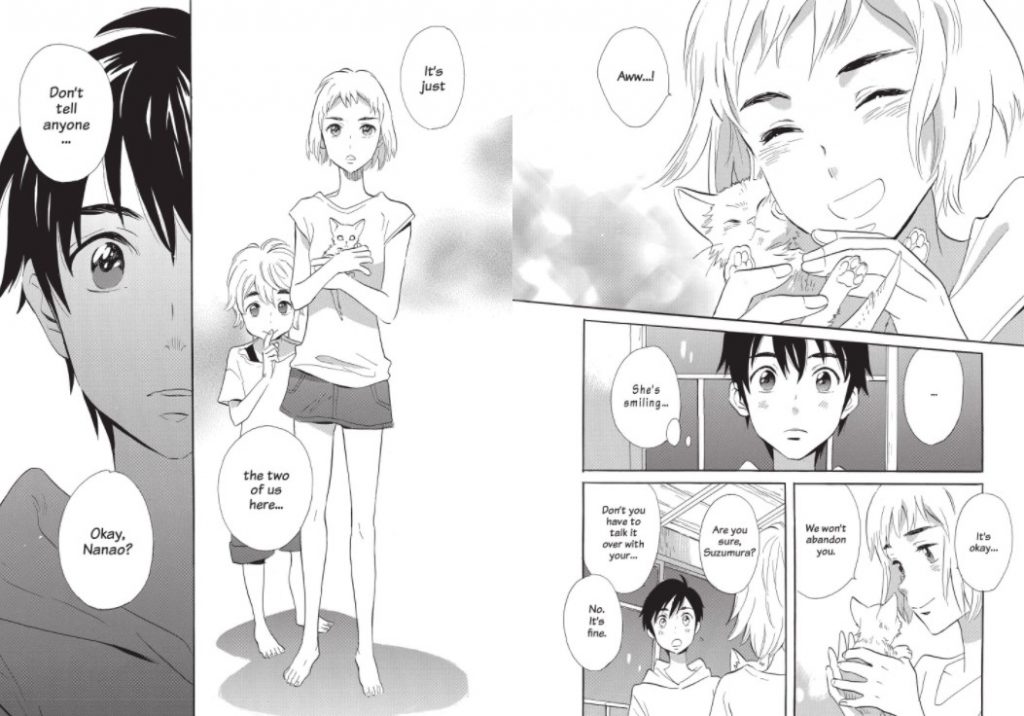

In the first half of the manga, we are treated to small scenes that are easy to gloss over but explain so much of the inner workings of this sixth-grader and her struggle to keep it all together. When Natsuru comes over one day, he observes her making dinner in her family’s home. She’s making tuna burgers by hand and he is impressed as cooking has always seemed like such an adult task that he’s never had to think much about nor attempt on his own. He exclaims: “We’re only in the sixth grade!” He then realizes that at home, his mother has always made meals or paid for them to be delivered, he, himself has never had to be the (temporarily) head of his household and make sure that those dependent on him eat. He’s never had that responsibility dropped on him. He’s stunned and is sure to tell Rio that she is amazing for knowing how to do this, not understanding the full story of how she came to be in the situation that forced her to do so.

In another scene, after Rio takes out a piece of paper and goes through the weekly household budget and lists of needed items, she, her little brother, and Natsuru head to the grocery store. They stop at the local bookstore on the way and the boys head off to read that week’s edition of (Shonen) Jump. While the boys are engrossed in comics, Rio picks up a recipe book titled “Easy Recipes That He’ll Love”. One could assume that it caught her eye because of her budding feelings for Natsuru, yet I’d like to add the possibility of her attempting to stretch the meager food staples that they had on hand at home for meals.

Lastly in that same chapter, while picking up groceries, Natsuru sees Rio admiring roses. When he questions if she wants some, she dismisses them saying it is “not something that they need” and moves them along. Later, after we learn of the fate of the grandfather who is buried in the garden, one could assume that the admiring of the flowers could have been wishful thinking in a way to more properly bury him. Yet I think back to her words and her body language during that scene: she’s focused on feeding and taking care of the still living and surviving members of her family: her little brother and herself.

Even if she just wanted the flowers for herself, just for the heck of it, she couldn’t buy them because she’s not a normal middle schooler with an allowance. She’s the head of the family trying to keep food on the table. Yet, later, when Natsuru disappears and brings her wildflowers, her face lights up on the page. No matter how many responsibilities are on her plate, at the end of the day she’s still a kid. She’s still a little girl who is happy to receive a gift from her crush and plenty of moments like this peek out in the narrative reminding us of the child behind the person she has to be, because of the unfortunate situation adults have put her in.

Instead of garnering any sympathy from the press or even her classmates at school after her story is revealed, it is heartbreaking to see Rio treated so badly. Her attempt to keep her family together, the burying of her grandfather, none of this was seen as heroic; she is, instead, treated as a leper or a social pariah by nearly everyone. This leads to Natsuru getting into even more fights at school defending her after the news dropped and the proper authorities were notified.

Interesting enough on the topic of gender: towards the end of the story, Natsuru’s mother remarks that if Rio’s mother had been around and had been the one in the father’s place: to abandon her kids–she would be crucified by neighbors and press alike, which is exactly the opposite of what happens to the father. That scene itself left a bad taste in my mouth as I think back to the other times the manga drops hints about societal expectations of women through the book — starting with Natsuru, the relationship with his mother, and how other adults see her.

For example, in the first chapter, the new soccer coach, after hearing that Natsuru has no father, remarks that he has it rough as a little boy. Natsuru’s mother remarks to him later in the manga on more than one occasion that she struggled as her husband passed away from cancer early in their son’s life. Regardless of struggling (and being treated poorly as a single mother from time to time) but doesn’t regret birthing Natsuru or marrying his father who passed away years ago. Natsuru knows that his actions, like talking back to the soccer coach when he’s rude or tone-deaf, don’t help the image of his single, widowed mother, so he tries to be on his best behavior early on and hold his tongue. By the end of the manga, after the town learns of what happened at Rio’s house, he cares less about these sorts of things and cares more about defending Rio from the unkind children at school. This is important to take note of when we, readers think about the overall story with Rio and Natsururu in mind with the themes of gender and societal expectations in mind.

I try to think of this manga’s narrative with the gender of Rio reversed and I just can not see the same result, the same story playing out. I can not. We know that girls and women are held to higher standards regarding children and family life, it is expected by the patriarchy, and this behavior is normalized to perpetuate it. We have seen examples in other manga of girls who have to make do with supporting their families and sometimes being the temporary heads of their households. We’ve seen them become pseudo mothers and caregivers in the name of parents that leave them to their own devices, too young to give consent to the work that needs doing. In media from television shows to animated films to comics, I don’t see many examples of young boys taking on these roles. If “art imitates (real) life”, then the gods lie is speaking to acknowledging the gender divide of responsibilities that wash over girls in waves and the cost of it.

In the realm of young women and adolescence outside fictional worlds, the pandemic has given rise to countless stories where teen girls have no time to be children. Because of the pressing need to be caregivers to younger siblings or aging grandparents in the home, many of them are tackling more than ever, taking care of others dependent on them. Many young women joined the workforce and are now working more outside the home to bring in much-needed income to households suffering from layoffs and once healthier adults suffering from health conditions and long Covid brought on by this global pandemic. Real-life Rios are being created every day, not just here, but in other countries and parts of the world, making such things as school, socializing with friends, and preparing for their futures less important and placed on the back burner. More and more young women are taking on the emotional labor of running households, the parentification of their lives is becoming normalized.

Outside of her friendship with Natsuru, Rio was not given the space to be vulnerable, to confide in others, or to generally have a support system. Taking on all the emotional labor meant that she was effectively giving up parts of her childhood and growing up too soon. Natsuru, by association, was too, after learning her secret and not having true agency to help her in the way adults could and eventually did. As I read through this manga I pondered on the cost of children, growing young adults on gaining more responsibility.

Growing up, in some sense, means gaining a taste of maturity, but for these children, it is a cost that is too high. For Rio, it’s the cost of her childhood, which is a price too heavy for a child to pay. For Rio, it was losing the only parent, her father, as irresponsible as he was, to authorities to be held accountable for abandoning his children. For Rio, it was being separated from the only home, the only place of stability that she’s ever known.

Kaori Ozaki remains a mangaka whose work involving the lives of young adults resonates in this pandemic age. the gods lie serves as a brilliant one-shot volume of manga that emphasizes the utmost importance of narratives about children forced to grow up too soon. This manga has a layered narrative that not only explores a young girl’s struggle with adults failing her, but also how damaging societal expectations and obligations can be regarding gender and home. Alternatively, her male peer chooses to involve himself in her life and receives the lesson of not just the limited agency of children but how their experiences will differ with gender and a stable parent and home.

For young Rio, her character arc traces her evolution to a young woman forced to grow up too soon, with burdens placed on her shoulders too fast in an unforgiving world marked by many that failed her. While this is most certainly a manga that pulls at the heartstrings, it is a shining example of Kaori Ozaki’s brilliance as a creative. Rio’s situation of being abandoned is an issue that exposes the phenomena of parentification and the traumatizing effects that befall its young victims. Without a stable support system, this young girl does not get very far as the temporary head of her household and the emotional labor on her plate constantly grows day by day with little regard for her own needs and desires.

the gods lie centers on a narrative that speaks to not just how damaging parentification is, but why everyone, especially children, needs support systems. Most importantly, Kaori Ozaki lights a fire in me, not just as a lover of manga and comics but as a media scholar, to seek out other representations of the toil of emotional labor placed on adolescent girls. It is a curious case, a situation that is not always centered in literature, much less comics, one that has become more and more pervasive as the pandemic continues. Stories about girls in comics and manga are always necessary and the gods lie is a brilliant self-contained story in one single volume exploring one girl’s struggles in a world of adults that have failed her and how the help of another child served her better in the end.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply