Urusei Yatsura is a difficult comic for me to write about. I have attempted many times this past year to write an essay about the series and have halted, finding my ideas too complex in scope to put into words coherently. In part, there is the simple challenge of writing about a lengthy, episodic comedy serial – if I speak generally, I say little to nothing about the work and end up talking around it, but if I go for granular specificity I either end up with a chapter recap or a byzantine tapestry of details which only I can unravel. There is also the matter of this being one of those few and fortunate manga which received an anime adaptation as idiosyncratic and unique as the source material; my relationship to one work becomes difficult to untangle from the other. Ultimately, the trouble is that I am a fan of Urusei Yatsura — I feel this series on a deep, embarrassingly passionate level. I indulge in ephemera of the franchise with an emotional intensity which many would reserve for their religion, or their ponies. My apartment is decorated with plushies of Lum and Ten, I have imported fan magazines and vinyl records. Lum and her friends are real to me; I have a relationship to them, and I do not like writing essays about relationships to pop culture icons.

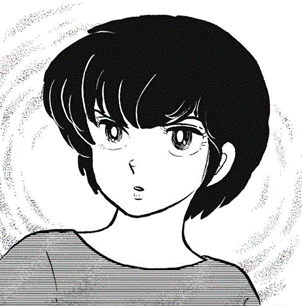

It was probably never Rumiko Takahashi’s intention to create a gift to trans lesbians when she set out to create a long-running sci-fi comedy for Shonen Sunday, but that’s what Urusei Yatsura has been for me. I began reading about a year before I transitioned, and, in an odd way that I find difficult to talk about without exaggerating, I found through the manga a myriad of beautiful examples of how many different ways that a woman can be. The girls in Urusei Yatsura are powerful, cute, bitchy, playful; Lum is utterly unstoppable but she has interiority; everyone wears a million different great outfits and expresses anger, frustration, joy, and confusion in an endlessly moving cycle of comedic action.

In an essay recently translated by Jon Holt and Teppei Fukuda in The Comics Journal, critic Natsume Fusanosuke opines that “For Takahashi, gender is something like a softball which can be squeezed into the shape of gourd that has both a male end and a female end.” Urusei Yatsura, I feel, explores the female end of the gourd. The manga plays with a spectrum of expressions, emotions, tones, styles that girls can have, an almost psychedelic range that transcends what boy’s and girl’s comics had ever shown before. The gender trouble of Urusei Yatsura is one where butch and femme, cute and sexy, demure and aggressive endlessly transgress on each other in a bubbling cauldron of identity and possibility. A shy girl throws a desk, an alien goddess cozies up to a sleazy delinquent. As I set out on my own gender journey, I was (and still am) exploring my (trans) womanhood, but also declaring it. Like the girls in Urusei Yatsura, I am as proud as I am confused, uncertain, exploring, still growing, and changing. So it’s potent stuff for me in addition to great fun.

In Urusei Yatsura I can find and construct allegories of my own experiences. Some of these are flimsy, a few might actually be offensive, some are very precious to me, but I will spare you. This isn’t exactly anything special. Even a little bit of time on social media will inform you that trans people spend a great deal of time excavating metaphors for their lived experiences from pop culture and stories that they connect to. In part, this might be because we largely lack a popular culture of our own, “trans representation” that does exist often seems only to serve our so-called allies’ malformed misreading of our lives. It is also simply intuitive, to find some part of us in stories, characters, and imagery and tell our stories through those pieces. On some level there is also an awareness that some of these stories may have been intentionally trans, an auteur may in fact be closeted just like we were; The Matrix is a notable example of a time that this was actually proven to be the case. And yes, very often these readings are a form of conspicuous consumerism, little more than self-branding and potentially embedding toxic capitalist messages into our very identities, but I will not moralize on this, not here anyway. Tedious people may call these “counter readings”, but I, for one, despise this term. If the meaning is there, if you or I found it there, how is this inherently “counter” to the text? But I digress.

All of this said, Urusei Yatsura is not in any way trans art or a transfeminine work, but my trans femininity informs my relationship to the work. I have excavated my own trans womanhood from its pages, interpolated my gender in the gutters between panels.

So.

What happens when fifteen volumes (eight in the Viz omnibuses) deep into the series, I am introduced to a new character, a girl who has been raised to live as a boy, who knows that she is a woman, longs to wear women’s clothes, and very literally fights for an opportunity to present as feminine?

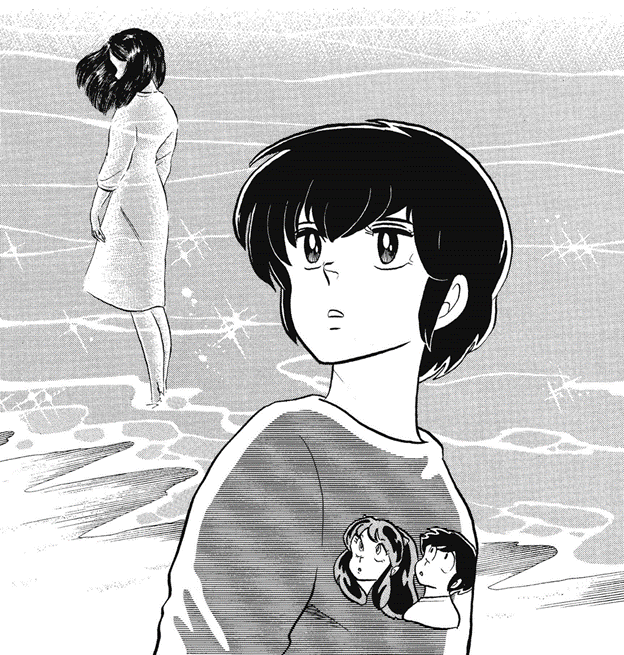

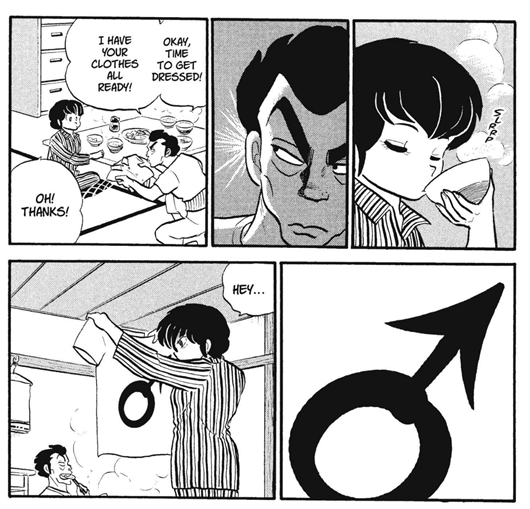

Ryunosuke Fujinami works at a beachside cafe, a failing tourist attraction, the family business. Ryunosuke’s father is a single parent eager to raise a good, manly son to inherit and rescue his business. Ryunosuke, however, cannot conform to this expectation on a basic spiritual level – she is his daughter and has no desire to be her father’s son, let alone to inherit his business. Her adolescent chest bound up in a tight weave of bandages, Ryunosuke’s father withholds all indicators of femininity from her, to the point of teaching her elaborate lies about the world. However, the appeal of womanhood and its conventional trappings – dresses, makeup, bras, dates – only becomes more powerfully compelling to Ryunosuke. Her father’s daughter, trapped in a ludicrous world of imposed and ineffective “male” socialization, she battles her paternal nemesis to achieve her dreams of wearing women’s clothes and being the woman that she self-evidently already is.

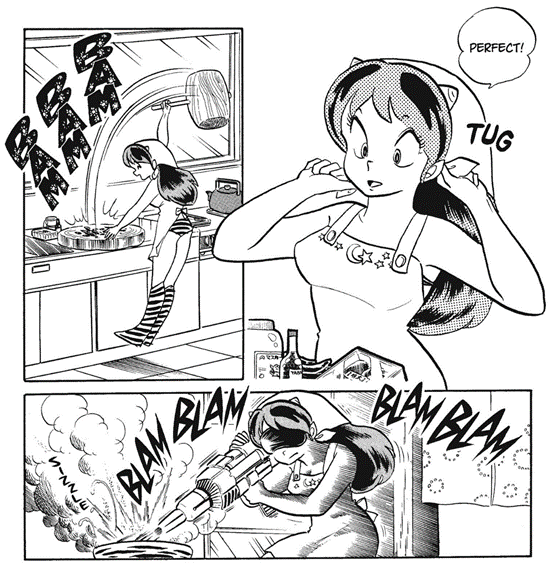

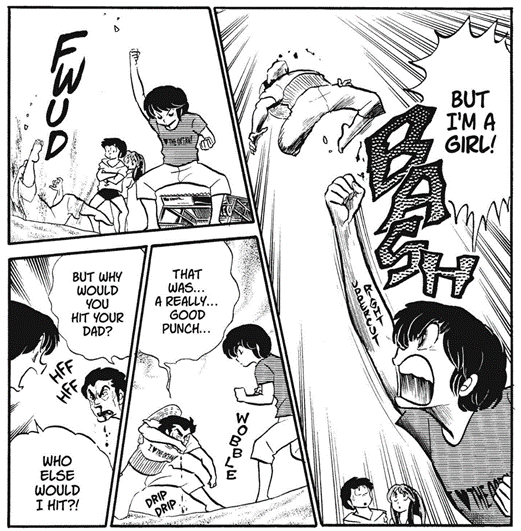

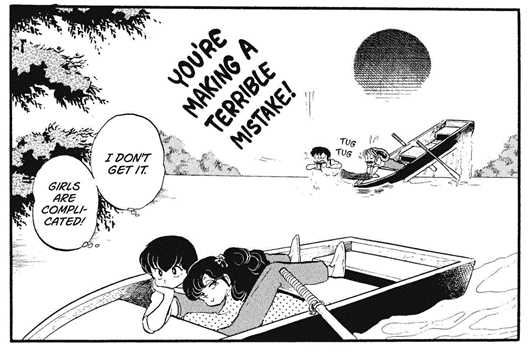

Ryunosuke has been raised within a world of her father’s creation – often the comedy is not so much about her “gender-bending” presentation as it is about her confusion about the very basics of being in the world and her strain to overcome the grip of her controlling parent. She is introduced performing a bizarre daily ritual with her father of cursing the ocean for failing to provide stable business year-round; by the next chapter, her father allows her to attend the high school in Tomobiki (after fisticuffs) under the condition that he literally move into the school as well along with his humble tourist shop. Her life is an endless tug of war with her father, always a few meters away, ready to interrupt a moment of budding womanhood with a flying kick to the jaw or to wave a sailor suit as a reward for victory in one-on-one combat. These passionate martial arts circuses might be called macho were she not so clearly butch, and were her father not so clearly ridiculous. Nonetheless, Ryunosuke wins many suitors among the girls of Tomobiki high.

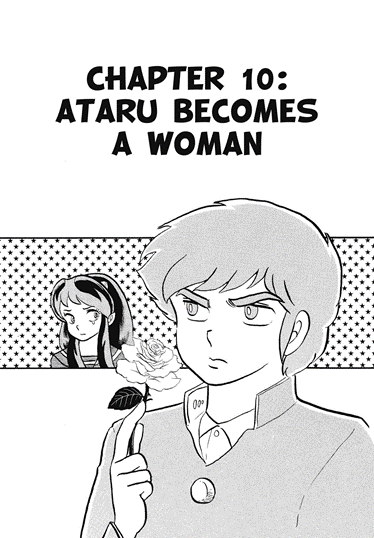

Frequently, Ryunosuke is mistaken for a man, but the joke is not so much that she is a man-like woman but that she is clearly and immediately superior to all men who exist in Urusei Yatsura, the lot of which are slobbering lecherous fools. A failed attempt to transform Ryunosuke into a man by a group of space crows (long story) unwittingly swaps the sex of pervert protagonist Ataru, an interlude that (very) briefly implies he might be happier and kinder as a girl. Ryunosuke does not understand that girls are attracted to her – in an incredible chapter, Lum’s rival Ran asks Ryunosuke on a date (in order to make Lum jealous, of course) which Ryunosuke accepts under the impression that she is being given the opportunity to learn how to act more like a lady. She picks up feminine etiquette from watching Ran’s every movement carefully; what Ran sees is a chivalrous and handsome man, gazing on her, intent on seducing her. The gap in context ultimately leaves Ran an ignorantly budding sapphic and Ryunosuke even more confused about the basics of womanhood; the basics which she merely fails to grasp being that there are none. The opportunity to become a woman is simply to shout, loudly and truly, that you are one. The next step is to live as one. She has already achieved that first step, but her voice is squashed down, by her father’s opposition, by the confusion of others, by the assumption that she has to do more first before she can just be herself alongside some very real roadblocks to her doing just that. And so, she fights, as a girl wondering what it would be like to be a girl, wondering if she will ever understand girls enough to be one, if she will be strong enough to tear away a shred of femininity from the hands of her patriarch in a battle that doesn’t make any sense and truly shouldn’t be necessary.

This isn’t a trans narrative, nor is it an “allegory.” It’s a gag, a running joke, with the deep characterization, escalating stakes, and keen insights Takahashi brings to such things. It’s a gag imagining a ludicrous origin story for the existence of tomboys. There is also perhaps some play on the beloved women disguised as men of year 24 group shojo manga, themselves inspired by the female drag of Takarazuka. Rather than the girl disguised as a boy being a glittering Lady Oscar, a variation on the idealized young man of girl’s romance, Takahashi’s girl prince is a rough and tumble athletic outsider, the archetypical young man of shonen sports manga. Integrating clashing motifs from prior shonen and shojo manga, Takahashi prods at the diversity of young women’s experiences largely ignored by both genres in a series nominally for teenage boys. This potentially transgressive yet very commercial and nerdy gender play is a continuous preoccupation of Takahashi’s work, as is the conflict between youth and overbearing elders – this is what Takahashi does.

Read as a direct allegory or analogy for real gender nonconformity, Urusei Yatsura and Ryunosuke might immediately appear heteronormative, bioessentialist, and cissexist. And yet, there are aspects of this character and her struggle that, in my life and the lives of many trans women I’ve known, are almost literally real. I have always been a woman for as long as one could be considered to have a gender, but I didn’t always know that. Well into my adolescence I didn’t know that being the kind of woman I am was possible or permissible, because nobody told me, and the first impressions I was given of the womanhood that is mine were misleading, hurtful lies designed to keep me from claiming it was mine. When I knew that I was a woman, I was willing to fight to live as one, but what I didn’t know was that I didn’t have to fight to become who I am. I didn’t need to survive hardships or become a warrior to be the woman I already was. That was something other people decided for me. Maybe it’s selfish and blinkered to see myself in a character, but I see a little bit of myself in Ryunosuke. I see a little bit of so many wonderful people in my life who have fought the ridiculous, turbulent endless fight for permission to express their gender and become who they already are.

Ryunosuke Fujinami, like me, is a girl burdened by the misfortune of having been assigned male at birth. The assignment of masculinity was not imposed upon her by her body or by any form of “biological” sexual dimorphism but by her father, who raised her in isolation, sheltered from any direct experience of normative femininity in her childhood, under a strict regimen of masculinity peppered with the occasional selfish lie. Ryunosuke grew up unaware that treats like chocolate and cake were delicious, but, despite the distortion she was raised within, she knows that she is a girl. Her conviction in her femininity is as fierce as her feminine form is obviously apparent, she is furious about the denial of her girlhood and longs for dresses, skirts, bras, lipstick, and etiquette. Nonetheless, she presents as a brash tomboy, brawling and cussing on the rough and tumble path her father set out for her.

Ryunosuke is a woman. She was born a woman, she lives as a woman. But she has been forced by her father to live as a man, to conceal her femininity, and perform masculinity. She is not, however, “socialized male” in any sense — she knows that she is a woman and is pained by her obstructions to present as such. Her desire to wear the girl’s high school uniform is not a perversion but an earnest longing to be allowed, accepted into a space where she can be seen and accepted as who she really is, who she knows she is. It would be reasonable for her to ignore her father, to simply go out and wear dresses. She can live as a woman regardless of what her father thinks, what clothes she wears, what vocabulary she speaks. Everyone already sees her as a woman. Yet the boundary to that life, the life where she gets to just be her gender without doubts, without conflict, seems always just out of reach. Her confusion towards aspects of femininity is comedic but completely understandable, the humor rooted in the specific peculiarities of her struggle to approach something so mundane as wearing women’s clothes as a woman. Likewise, her strength and brazen temper do not offer proof that she “is a man,” but reflect her absurdly unfair upbringing while underscoring the most important lesson that Urusei Yatsura has to offer readers young and old: that women can, in fact, be strong, can do anything just as well as any man, can be whoever they want to be, and can stand up to anyone who tells them otherwise.

Urusei Yatsura never resolves conflicts. Love triangles and miscommunicated romance are like an endless curse; unfulfilled wishes are abruptly averted. Parents, teachers, elders never seem able to truly leave the kids alone, not for long. But everyone has power. Everyone has a presence, personality that cannot be repressed. All girls can demolish a building single-handedly if they are angry enough. Ataru Moroboshi, the epitome of a confused lecherous teenage boy, can recover from a beating doled out by any enraged lady forever. Ryunosuke is never going to wear a bra or a dress, not for long. Her father will always be somewhere close behind, ready to fight his “son.” She will never know herself enough to learn what she wants because Takahashi and her editors did not create a franchise where that can occur. For better or worse, it’s an eternal summer. The path of Ryunosuke’s gender journey stretches out as an endless beginning. But, nonetheless, she is a woman. She knows she is a woman, she is seen by all her friends as a woman, and she can scream that she’s a girl while punching someone so hard that the force of the blow sends them flying into the stratosphere. Her knowledge and her power tell a story about gender that doesn’t need an ending. It’s a story about transition, about knowing and not knowing, standing up for yourself and retreating, being understood and being misunderstood. And, for many of us, her story is true. Her transition is one that I lived through. I have met Ryunosuke and she is a trans woman, maybe every trans woman I’ve ever known. I bought her dresses.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply