A trans lesbian reflects on a slightly embarrassing high school crush on the nice lady from Maison Ikkoku

January 2020. It’s past midnight, and I cannot sleep. I am buzzing with energy, overflowing with knowledge and love. I want to scream it, embarrass myself in public. Nobody would really remember, gossip isn’t memory anyway. If I exhale those words, if I breathe them out loudly enough, it becomes real, it becomes me, and perhaps some kind of presence could will emerge to heal me. If I can let the noise escape I will finally relax. I can’t do it yet. But my thoughts roar the words that I cannot bring myself to say: I am a woman. And now I will always know it.

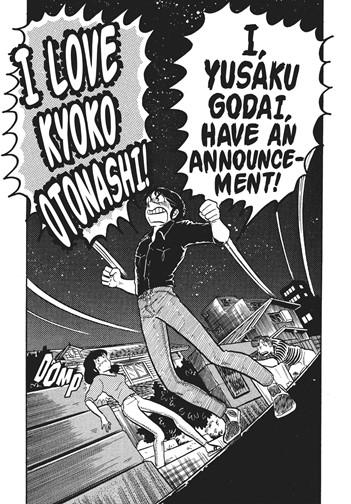

Someone’s voice is booming in the middle of the street. A man’s voice, the man is, of course, fictional, his voice is all printed ink too, “just lines on paper” as someone once said about every comic book. Anyway, this fictional man, Yusaku Godai, is fictionally drunk out of his wits storming down a fictional street declaring his fictional love for a fictional woman, Kyoko Otonashi, the new manager of the titular fictional little run-down apartment complex. Without the fictional booze, he would never have had the fictional bravery to declare his fictional feelings. After tonight, the hapless young man and bewildered young woman will find a way to make this a secret they hide from each other once again. But the voice has been released. We know.

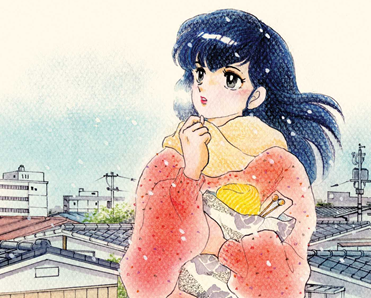

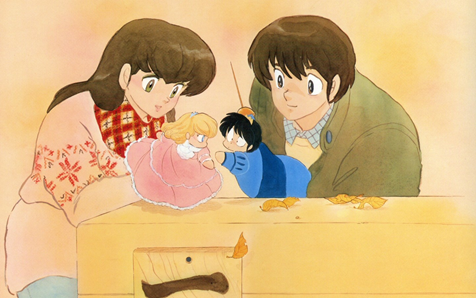

Godai won’t have to worry about me because I am a very real woman and I don’t date 2D heterosexuals, but I also love Kyoko Otonashi. I first met her when I was twelve years old, just a girl, in the pages of 15 little paperbacks on a shelf at the same library branch where the Classroom Drifted before my eyes and I visited the town infested with spirals. It was love at first sight. Everything about Kyoko filled my mind. I was at an age where beauty, femininity, and kindness were subjects that kept me awake at night for reasons I didn’t understand. I loved her and I wanted to be her. Yet wanting to be a woman wasn’t an emotion I was ever really told about at that age, so I figured that I just “wanted” her, and, since lust was a disgusting idea to me, I simply decided I “loved the comic.” I spoke about Maison Ikkoku (mostly to people who didn’t really want to listen, I was a compulsive little autist girl) in terms of a literary masterpiece, the real art my classmates would never understand. This embarrassed me deeply when I was a little older, and my fixation on this incredible woman embarrassed me even more. I left Kyoko and Maison Ikkoku behind without stopping to ask myself why I had loved her. But it became clearer to me as the years went on that my fantasies about a beautiful and humble housewife were fantasies about myself. Kyoko’s chipper domestic life as manager of a household of sorts, her long, flowing hair tied into a practical ponytail, the flash of her eyes smiling calmly as she rakes the leaves in the yard, sleeves rolled up slightly, that adorable apron… this is who I wanted to be.

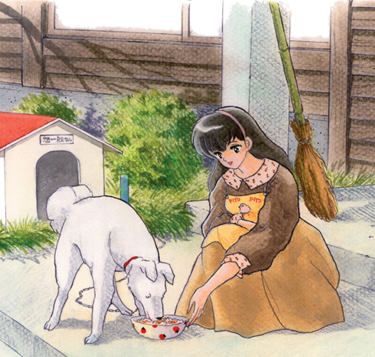

Meeting her again now, in the convenience of higher quality omnibus reprints with a new and superior translation, a few things surprise me about Kyoko. The first is that I am now two years older than she. If this comic were made today, the fact that a widow turned apartment manager was only twenty-two would be a major plot point, and everyone would be unbelievably impressed by her career stability to the point of envy. Kyoko has a lot of basic peace in her life that a girl like me can only dream of, but, like me, she is a young woman who, by sheer circumstance, has lived enough life and enough tragedy to have experiences and emotions beyond her years. She fell in love young, she married young, she started the beginning or the rest of her life young. Her husband Soichiro was sickly and died young, their married life ended young, the man for whom she defied the will of her controlling and domineering parents was gone and, with him, the future she expected. But she carries on in his absence and with his absence; Maison Ikkoku is owned by her late husband’s family, whose family name she keeps. Kyoko lives there and works there and carries out a life there alongside her dog( named Soichiro after her husband because when she called for her husband he would come too). She is devoted to her husband’s memory and, perhaps, contained by it as well, but, more so, she is steadfast on continuing the life she started as a homemaker and a member of the Otonashi family, with the company of her tenants to keep her spirits lively.

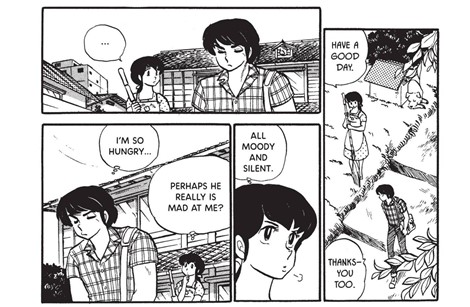

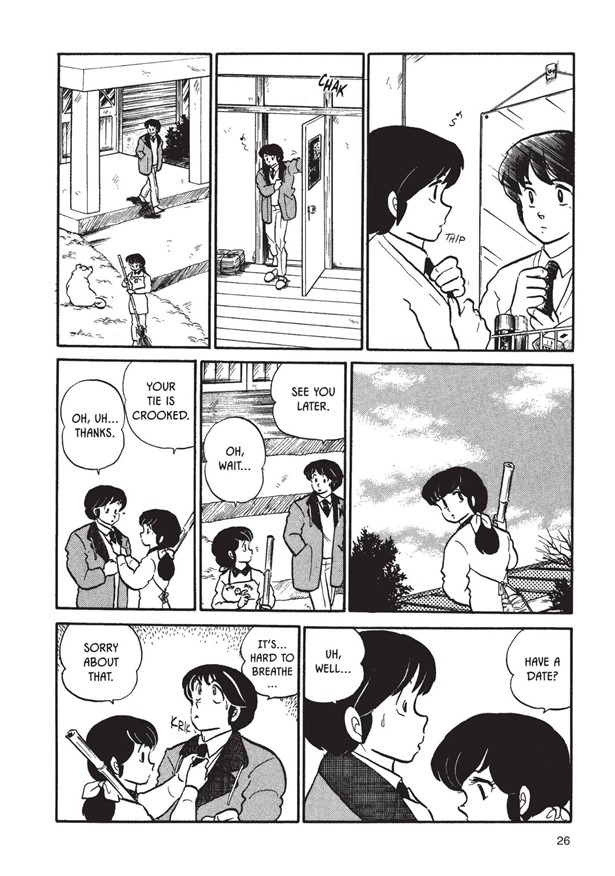

Maison Ikkoku is a familiar episodic comedy-melodrama powered by a familiar question — will they or won’t they? — and a familiar answer — maybe next time. The reader waits eagerly for the beleaguered college student Godai to ask his gorgeous apartment manager Kyoko to go on a date with him, for Kyoko to say yes, and for a relationship to blossom and begin. Every chapter is designed to almost cause this event, yet prevent it, whether by an untimely interruption or an unfortunate misunderstanding. Still, all the chaos and removal and pulling apart is time and again drawn to a close and settled by the magnetic center of the Maison, the makeshift home, never quite fulfilled, at least not yet, anyway.[1] What is so compelling and visual about the series is that the misunderstandings often hinge on as little as a misread expression, the assumption that one is angry when is, in fact, confused, fumbled attempts to carry on without saying anything while utterly puzzled about what the other is thinking. The zigzag velocity of Takahashi’s sight gags in Urusei Yatsura are honed down and refined into observational humor, psychological slapstick charting the leaps and stumbles of a yearning couple-to-be interrupted by their wonderfully compatible difficulty interpreting sensitive social cues.

There is a strangely dysphoric charge to the series, particularly once it drops the ill-suited sex farce antics of the early chapters. The turn follows that moment when Godai admits he loves Kyoko, loudly, drunkenly, in chapter 9. The confession is quickly undone — Godai’s neighbors tell the hungover Godai a very different account of that night’s events, Godai tells the beautiful landlady he was joking, the beautiful landlady slaps him, maybe next time it’ll work out. But now it has been said. And Kyoko heard him. The two of them go on pretending that they don’t know, but they do know. They just won’t say it.

The humor and tension of Godai and Kyoko’s non-relationship build into an odd sort of romantic domesticity that each takes great pains to not acknowledge, even while reacting against threats to this comfortable coupling. A typical exchange in volume four shows Kyoko fixing Godai’s tie as he heads out from the apartment, and pulling it tight enough to choke him when she realizes he may be heading out for a date. It is ultimately less a series about Godai trying and failing to win over Kyoko’s affections than it is about both Godai and Kyoko trying and failing to understand that Kyoko does, in fact, love Godai. Is there not something a bit sapphic about this pair, too shy to say they love each other yet practically U-Hauled into cohabitation at first sight? And is there not something a little bit queer about Godai’s spacey reverie, his fantasies about being with girls that seem to spirit him out of reality, drifting aimlessly through his life, advancing perhaps, but sleepwalking, while his hopes and anxieties about a beautiful woman occupy his mind, a different and more fulfilled life defined by her floating in a dream world just out of waking reach? And, ladies, aren’t his sweaters just ever so slightly futch?

Yusaku Godai confuses Kyoko because, despite everything she’s been through, Kyoko is still a young woman. Although a lifetime of experiences and emotions have come and gone with the departure of her late spouse, Kyoko is still very much at the beginning of her adult life. She does not really know herself; she does not really know her feelings. Much of what is loveable about Kyoko Otonashi, to the credit of Rumiko Takahashi’s storytelling, are her moments of interiority, and, in those moments, Kyoko is both hard-working and clueless. We see a life that is much fuller than the smitten Godai could ever imagine: her domestic and administrative labor in the apartment complex, her recreational outings and private rituals, her petty grudges, her casual friendships. But Godai is also unaware of how Kyoko thinks about him, constantly, unintentionally, rooting for him to succeed without quite knowing why, jealous when other women come near him for reasons she cannot justify, thinking about him in ways that do not make sense, defending him from tenants’ gossip which she could simply ignore. Kyoko does not ever reject Godai really. Rather, she lives out a life of confusion and gradual clumsy self-discovery complimenting Godai’s bumbling passion, two confused souls attracted to their beautiful awkwardness.

When I was younger, Maison Ikkoku was a manga about a man seeking to win the object of his affections. Now, to me, it is the story of an affectionate subject, a woman who is putting her life together under great strain after a trauma, finding herself drawn to a man who loves her just as much as she ought to love herself. Her life is as full as her fashion sense is impeccable, her womanhood is the womanhood I used to dream of secretly and it is not so different from the womanhood I live proudly now. No wonder I always loved her. No wonder I still do.

[1] No spoilers! 😉

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply