Reading comics is a mysterious process. While it’s been part of my DNA even before I could comprehend text, I know adults who find themselves baffled when presented with a comic book. Why? Because the simultaneity of apprehending and then comprehending both word and image is a learned process, not a natural one. So it stands to reason that the ways in which a cartoonist chooses to combine word and image has as much influence on the reading experience as the actual words and images themselves. By comparing two books that approach similar themes with different aesthetic approaches, focusing on the ways in which the artists use drawing and page design techniques to advance their plots and characterizations, this idea becomes obvious. The first book is 2019’s Taxi! by Aimée de Jongh (Conundrum International). This is a no-frills paperback book done in black & white that emphasizes light and shadow. The second book is 2018’s hardback Kingdom by Jon McNaught (NoBrow), and it’s very much in keeping with the NoBrow house aesthetic emphasizing soft, duo-tone colors. Like many NoBrow books, its design and presence as an art object is part of its essence. While these books share a similarity in theme, how they present that theme makes all the difference in the reading of them.

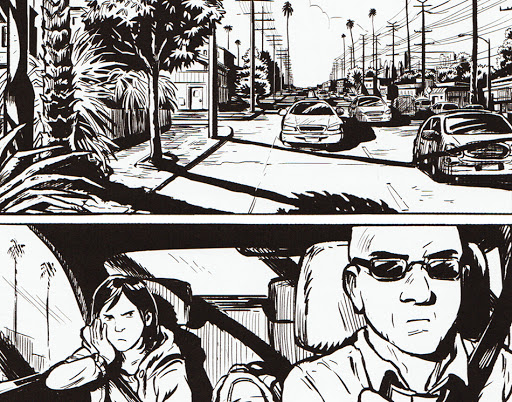

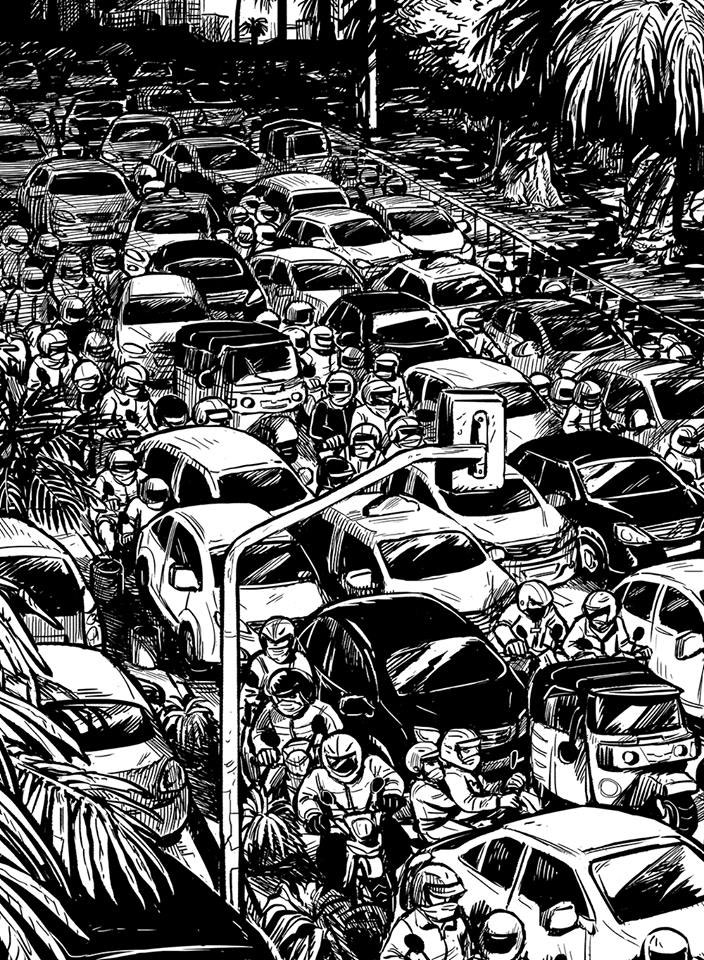

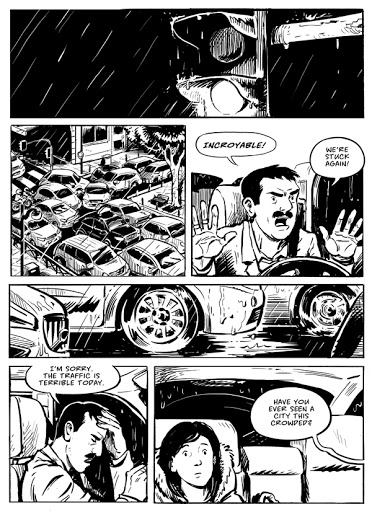

Neither of these books features complicated plotlines. Taxi! employs a fractured chronological timeline — where de Jongh tells the story of four separate cab rides in four different cities over a several year time span. Each journey is given a few pages and is then interrupted by another cab ride until de Jongh repeats the conceit. This works smoothly for a few reasons. Limiting the book to black & white gives de Jongh total control over the visual presentation of each city, allowing her to highlight similarities more than differences. Indeed, juxtaposition is de Jongh’s chief storytelling strategy, like in one sequence where her driver marvels over the density of Paris’ traffic, asking “Have you ever seen a city this crowded?” The next scene is in Jakarta, one of the most crowded cities in the world, and de Jongh plays up the jarring transition as a narrative device through the street scene jammed with cars and people. Repetition is a key structural tool for de Jongh, as the same kinds of visual cues also serve to recapitulate the emotional themes of the book which include ideas surrounding loneliness, alienation, and finding common ground.

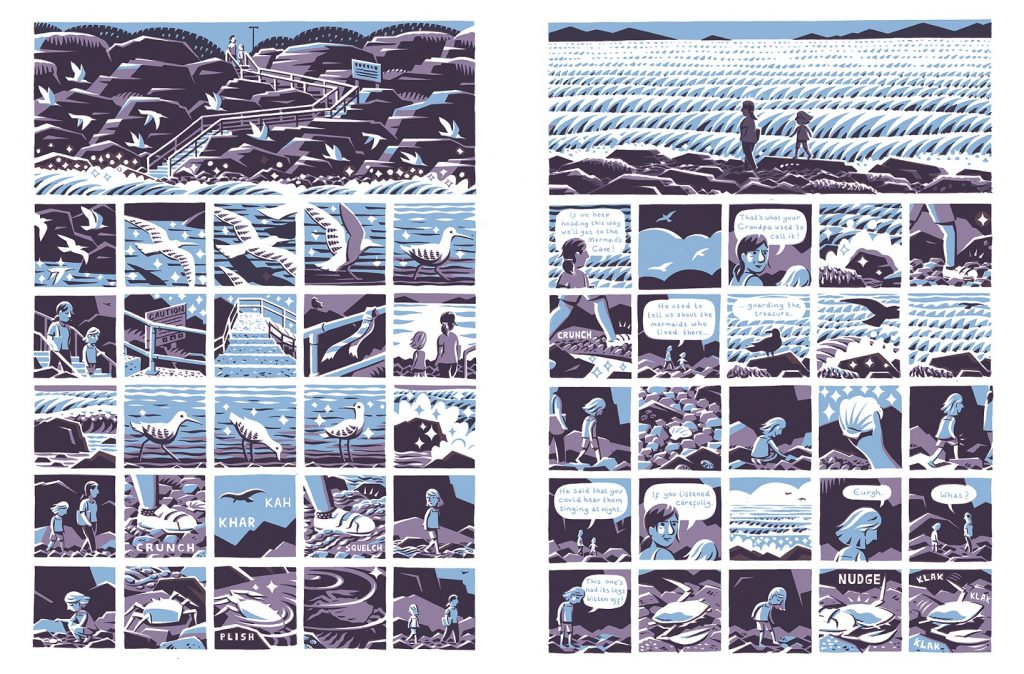

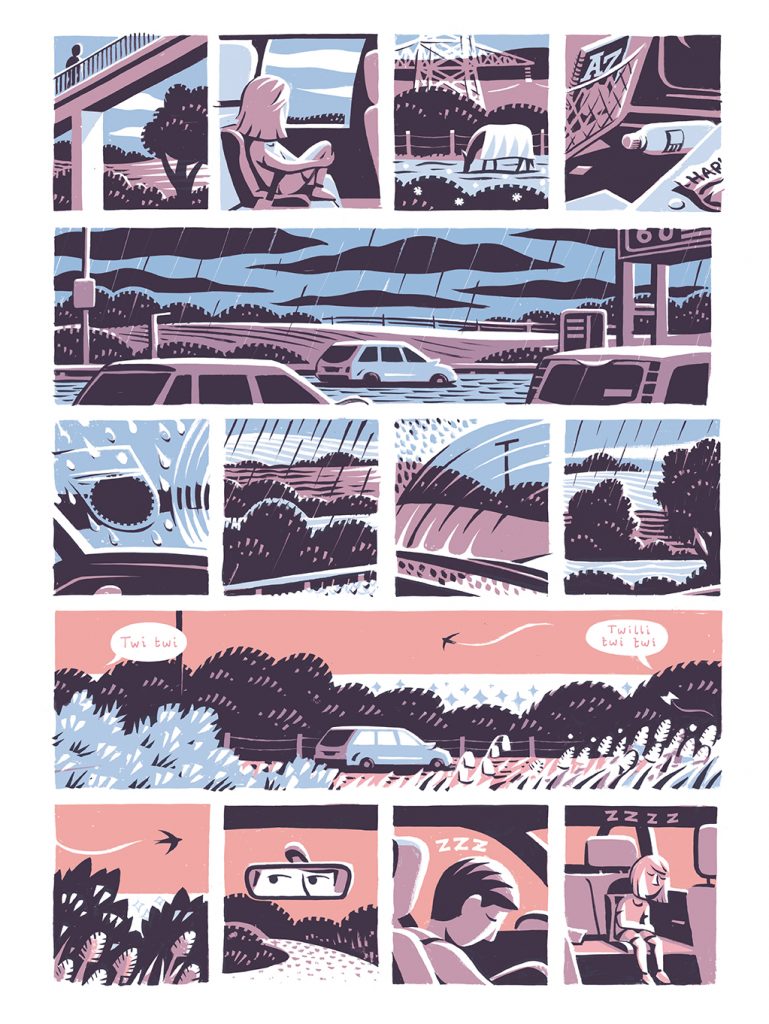

Jon McNaught’s Kingdom, on the other hand, follows the vacation of a single mother, her teen son, and her preteen daughter to a beachside town in England. The book simply documents their journey to their cabin and the small ways in which each character occupies their time on the trip. There are small fractures in the family that McNaught depicts by how they choose to spend their time together, as well as a mounting sense of disappointment on the part of the mother as she realizes that her memories of the place don’t match up with the current reality. McNaught uses color to represent melancholy and wistfulness, with rainy-day pastel blues and dreamy light pinks as the dominant colors. This is especially noticeable considering how simply he renders his figures; it’s an instance of color, rather than line, doing much of the narrative heavy lifting.

The main difference between Taxi! and Kingdom is that McNaught trusts his art to tell most of the story and de Jongh doesn’t. While Taxi! is based on de Jongh’s own experiences, her use of shadow and naturalistic drawing is steamrolled by the way she constructs dialogue. For example, the lively nature of one of her cabbies is obvious thanks to the way she draws his face: interesting eyebrows, light in his eyes, and an expressive mouth. De Jongh then goes on to hammer this home with pages of dialogue that’s supposed to feel spontaneous but is clearly edited to drive home the character’s story.

The whole point of the book is focused on the idea that despite differences in origin, culture, and religion, we have more in common with each other than not. Many of us have parents or grandparents who emigrated to start a new life. Many of us have religions and cultural customs that are important to us but also make us feel conflicted. Many of us are ambivalent about spending time with others. Each of de Jongh’s drivers has an easily-digestible narrative that encapsulates this, with her stand-in character’s cheery loquaciousness acting as a conduit for these stories. Her Los Angeles driver hates talking to customers but perks up after a radio story about Uber. Her Parisian driver is a Muslim whose main complaint is that Ramadan prevents him from eating all of the food that the City of Lights has to offer. Her Jakartan driver sneers at her being Dutch since they occupied Malaysia for three centuries, but he warms up to her when she tells him that her father was Malaysian. Her DC driver shares a traumatic event from his past that hindered his ability to drive for a long time.

Even with this fractured narrative technique, the stories in Taxi! feel repetitive. The connections that she makes also feel too easily achieved and even self-congratulatory, and that repetitiveness only emphasizes the artifice in each story. The dialogue leaves no room for ambiguity in this regard, as it’s clear that she makes a breakthrough in each instance. The rigidity of de Jongh’s page design adds to that sense of repetitiveness. Taxi! is obviously designed to provide a uniting aesthetic for each city, as each page has three stacked, horizontal panels that resemble the length and motion of a car. A different design scheme, a different drawing technique, or a different writing technique could have made this a more interesting book.

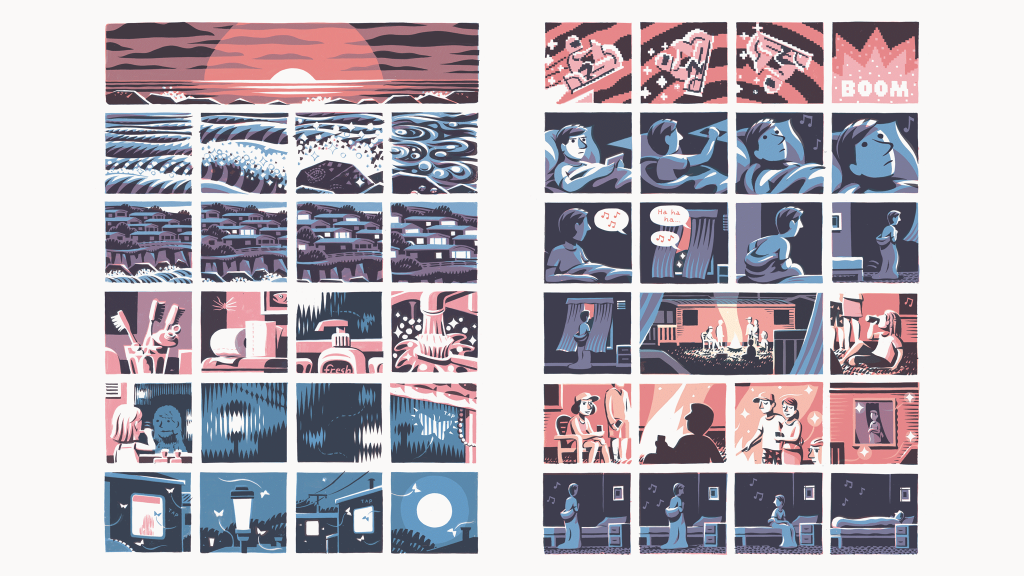

On the other hand, Kingdom has no grand series of big emotional reveals. Instead, McNaught loads his pages with small panels, each of which accruing detail, sometimes up to 35 panels per page. McNaught lingers on trivial elements, like the games in an arcade or fast food bought at a rest stop, as a way of highlighting how travel can make such banal details seem novel in a new context. McNaught appears to suggest that no matter how insignificant the event or detail, those memories linger on because of the liminal nature of traveling. Being forced out of one’s daily rituals, he suggests, makes one more aware of one’s surroundings and the passage of time in general.

Slowly but surely, through his visual storytelling McNaught reveals a few things about this family. The son is restless and is looking to connect with his environment, even as he is growing apart from his mother. The mother wants nothing less than to recreate the magic of her own childhood through her children, and finds herself failing miserably. The daughter is willing to go along with her mom, but the mother doesn’t see that her daughter is finding her own magic on the trip — it’s just different from what she experienced as a child. All of this is accomplished through panel after relentless panel, as McNaught shows us what these characters are experiencing rather than explicitly telling us about it through the narrative. We aren’t told that the son making a new friend (even if he is a bit odd) is an important, but still sort of ambiguous, event; McNaught makes it obvious through his use of fine detail, color, and tone. We see the daughter fascinated and delighted by discovering flotsam-and-jetsam like bottle caps, making her own distinct memories. That delight contrasts with the disappointment the mother feels when a cave she remembers from her childhood is in poor shape and trash-ridden. The trash for her, interestingly, is a treasure for her daughter. The same is true for the mother when she visits an old relative, as McNaught captures that sense of things not being as she remembered through a few subtle lines.

The poetic qualities of Kingdom and its themes are entirely conveyed through its visuals. All of the dialogue is strictly functional, yet it is in its mundane qualities that McNaught creates its magic. McNaught makes Kingdom’s quietude its greatest strength, as his equal emphasis on small snapshots of nature and the family’s quiet moments together speaks to the way that not all emotional content needs to be phrased as a series of revelations or epiphanies. Comparing this to Taxi!, de Jongh’s need for narrative closure at the end of each cab ride feels artificial. “Show, don’t tell” may be a storytelling cliche’, but one can see how it plays out in these two books. For example, in Taxi!, the reader is fed crucial information about the Dutch occupation of Maylasia by way of the driver’s dialogue, as a way of first establishing conflict and later establishing common ground. In Kingdom, the reader can rely on the visuals of the comic to see how the son quietly reconnects with his family by playing a game after having a chance to grow on his own during vacation. As far as the reading experience goes, the definitive quality of the encounters in Taxi! is less interesting than the ambiguous quality of the family’s relationships in Kingdom.

Both Kingdom and Taxi! are about the ways in which travel takes us out of our comfort zones and gives us the opportunity to create indelible memories and connections. Taxi!’s attempt at crafting a profound message feels unearned, thanks in part to the narrative shortcuts that de Jongh opts for. Kingdom’s ambitions are more modest and subtle, and McNaught happily takes his time in achieving them. Creating a balance between word and image is a tricky business. De Jongh tips the scale too far in favor of dialogue as a way of achieving narrative clarity, and as a result, her interesting drawings become superfluous. A version of Taxi! with stick figures instead of her expressive drawing style would have made for a better book, because the images wouldn’t have distracted from or replicated what she was saying. Conversely, McNaught nails that balance in Kingdom, as his dialogue supplements his visual storytelling without stepping on it. Ultimately, how McNaught and de Jongh craft their comics makes all the difference with regard to the experience of reading them. The former trusts readers to discern meaning in his comics through his technical choices while the latter opts to lead the readers by the hand.

Read more of Rob Clough’s work at SOLRAD

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply