Here’s the thing: there’s gotta be more than just this… right? This flesh that keeps us here, that keeps us centered, that serves as the platform for our interaction with the externalities of the world… that can’t be all there is, can it? I do not presume to be the first to ask these questions—no, this discussion has been going on for millennia, and the question of whether the body is the sign or merely the signifier remains unanswered, at least not in any way agreed upon. But we are told, we are bombarded with the presumption, that the wellness of the body dictates the wellness of the soul, that the spiritual purity of the signified is maintained by the cosmetic purity of the signifier. The body may keep the score—but for the low, low price of your cold hard cash, you can use all the creams and ointments you want to write a score of your own.

With Spa, recently published in English by Fantagraphics, comes Swedish cartoonist Erik Svetoft to call this thesis into question. Focusing on the inner workings of a wellness resort in Northern Europe, Svetoft presents his narrative not as one cohesive story, instead giving various storylines more or less equal weight, panning across them and going back and forth with the resort serving as a narrative locus. The casual abuse and berating of workers take place alongside business seminars; two lovers inadvertently replace the emotional decay of their shared love with the physical decay of the too-clean spa. It’s a from-the-top-down view whose attempt to tie together all these factors of social and physical dilapidation is clear, almost clear enough to undercut its own impact.

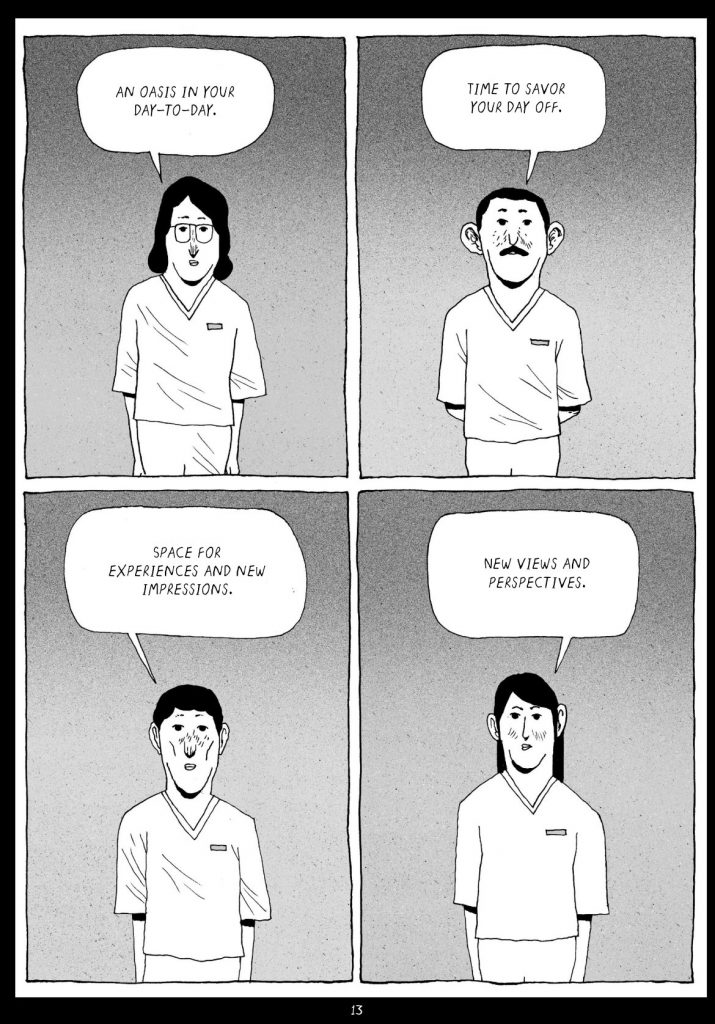

And, indeed, at some points Svetoft does defeat his own purpose, both formally and didactically – some of the scenes are divided by vignette-like interstitial illustrations, which attempt to condense the feel of the book into one full-page or double-page image, resulting in an unintentional questioning of Svetoft’s own choice of form: these illustrations feel less like a part of the book than like accompanying material, as though they were intended as a series of standalone illustrations that later ballooned into a full graphic novel; functionally using them as cutaway points comes across as a structural indecision.

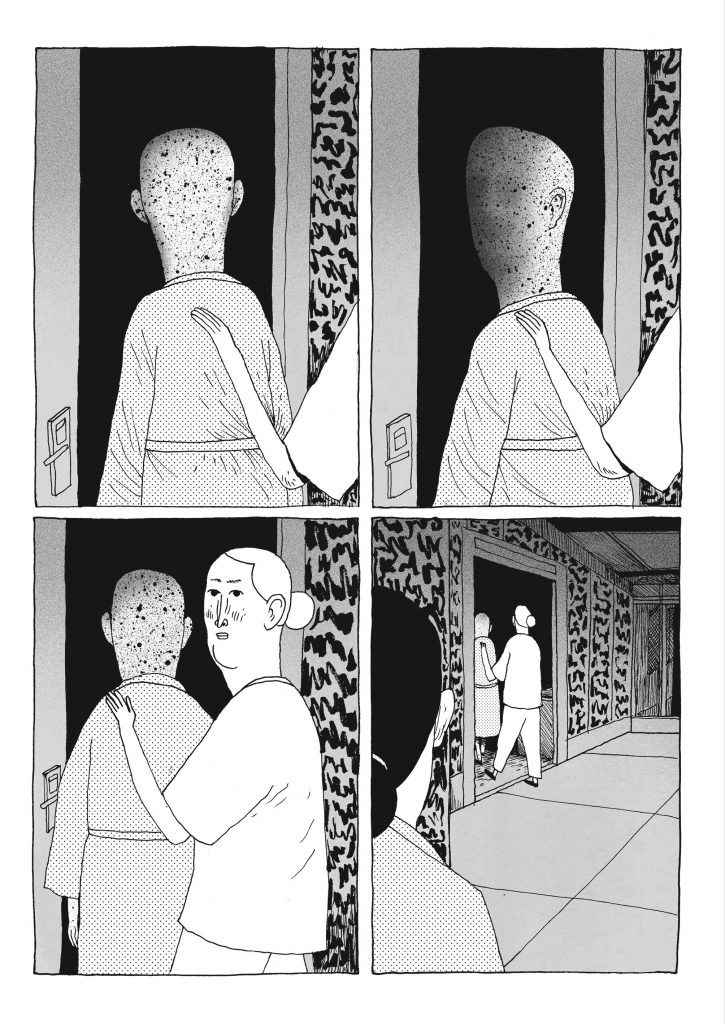

Still, Svetoft is a remarkable cartoonist, and the charm in his artwork is immediately obvious, in its off-kilter way. The weight of his line is invariably thin, and it outright refuses the straightness of a ruler, instead opting for the vulnerability of an unanchored movement, of an only-slightly-tremulous hand, creating a landscape of almosts, of skews and angularities that are not supposed to be there, especially not so far as architecture and piping are involved. His characters are elongated and spindly, with facial detailing kept to a minimum, as if defying his reader to connect with the characters more profoundly than the author does, and the horror imagery depicted is far more fleshed out and precisely rendered than the humans it affects, inverting the expected priorities so as to frame humans as an afterthought in a world that may be populated by them but certainly not dominated by them. We may have created the forces of capital, but we made the mistake of giving them sentience.

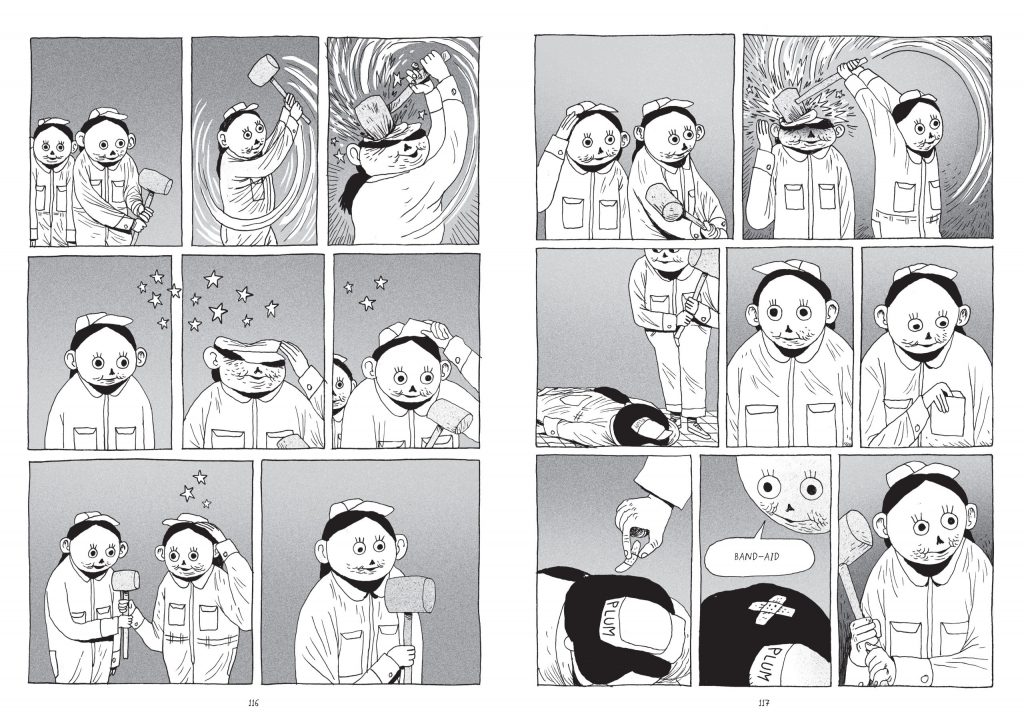

The acuity of the discomfort in Svetoft’s work emerges from the author’s efforts to make horror functionally indistinguishable from humor, and vice versa; Spa recognizes a structural tradition shared by both horror and comedy, a simple tension-and-relief mechanism coupled with a wrongness that acts not quite as a subversion of expectation but certainly as provocation thereof, and takes this mutuality to the extreme. The maintenance employees, easily my favorite component of the plot, are a good example of this: the two doll-like technicians, with their static smile and unblinking eyes, communicate in one- or two-word sentences and exist only as specters of slapstick. When one accidentally hits the other with a hammer and caves their skull in, the injured party simply pops their head back into wholeness; when the latter accidentally hits back, they put a band-aid on the former’s injury and immediately restores their health. They swing hammers at pipes and blow them to pieces, only barely capable of discerning “broken” and “fixed.” And it is these slapstick-specters that are charged with maintaining the wholeness—the wellness—of the dreary real. It works precisely because of Svetoft’s deadpan framing and refusal to remark on the tonal disruption, thus allowing a tonal subsumption that articulates the fundamental wrongness at the core of the world.

There are moments, though, that the deadpan act strains its vessel a bit; where the urgency of the horror narrative traditionally hinges on the stakes at hand, on the possibility of escape, Svetoft’s world is one of an apparently predetermined surrender. It is not clear that Svetoft sees a way out of its alienation and decay, and consequently takes on a “why bother?” hollowness that extends to a somewhat shallow narrative approach; his story takes the decay and alienation as a complete given, as fixed and as certain as the sun rising in the morning, and surrenders to them rather completely, its despair as final as a prescription.

The back-cover copy proclaims the book to be a critique of consumerism and the “wellness” industry, but its targets are deeper than that; the core horror of Erik Svetoft’s world is one indivisible from that division of body and mind itself, pursued to its logical conclusion. Its motivating fear is that of alienation, and the physical repercussions of it; the focus on the purity of physical health has the tendency to conflate the luxury of access with the value of the one accessing it: it alienates those who can’t afford it, or whose physical disabilities preclude them from this “wellness club.” The book’s nightmare scenario is the point at which wellness, as it is sold to us by resorts and skincare companies, buckles completely, revealing its real drives, its deeper filth: in the commercial realm, the profit is the body and the exploitation is the mind.

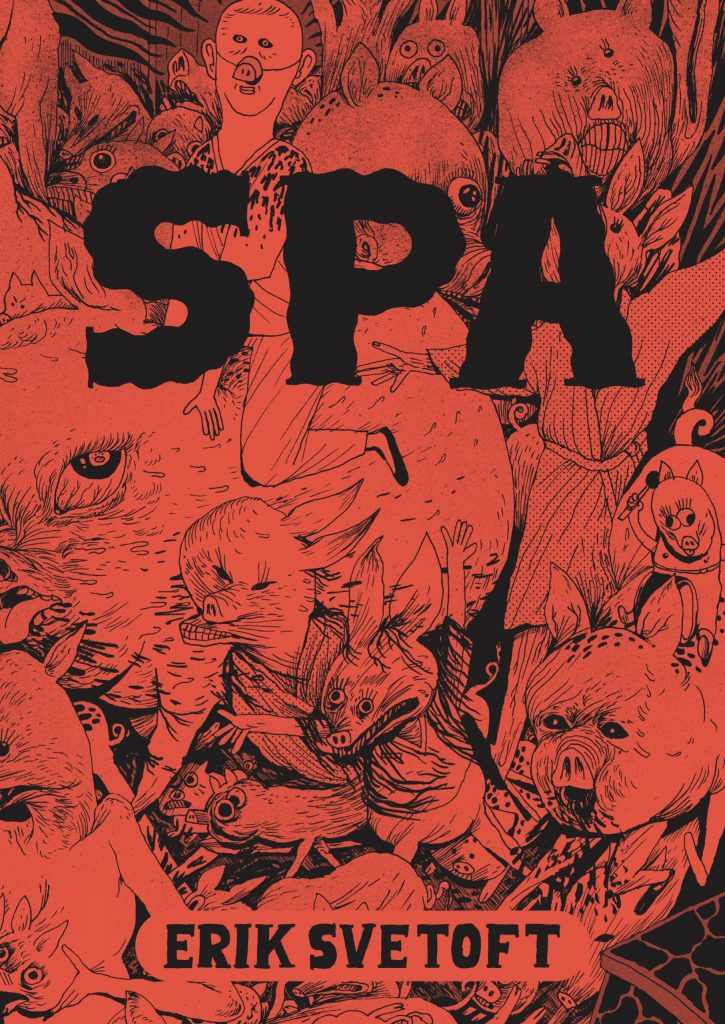

The wraparound cover of Spa, echoing a scene from the book, shows a man wearing a plastic pig snout as penance for his perceived inability to keep himself clean. He is not the focus, though—indeed, it would be easy to miss him because he is astride one pig amidst a porcine stampede; each pig is drawn in a completely different style, all of them cartooned to different extremes. They are, for all intents and purposes, pigs, bearing every bodily signifier we can recognize as pigs, but you would be hard-pressed to find two that look like one another. They are, all of them, of the same species; they are, all of them, completely alone, completely alien to one another.

And that’s just the thing, isn’t it? If we are just the sum of our body parts, we will only ever be able to engage in the sheerest externality. In Erik Svetoft’s world, we are all well; our posture is upright, our skin is taut and smooth, and we can all go about our day, disintegrating but nonetheless happy, free to mistake docility for contentment. In Erik Svetoft’s world we are all perfectly well—and look how far that’s gotten us.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply