Poster by Ginette Lapalme

Towards Critical Histor(iograph)y of Independent Comics

Canadian independent comics – whatever your definition may be – have managed to maintain their distinctiveness and independence from their Southern counterparts, unlike other art forms like cinema, literature, fine art, or music.

I have always wondered why, as I spend countless time and money at The Beguiling.

One of the most obvious reasons is that Canada is simply a better welfare state than the USA. It provides public arts grants, including comics, at federal, provincial, and municipal levels; a less expensive post-secondary education system (art schools) via public universities thus less pressure on student loan payment; free healthcare not tied to your employment; and so on. Such a social safety net is especially critical for a field like comics, where the material means are scarce.

Another aspect that deserves attention is the voluntary, grassroots infrastructure of artistic networks/communities including non-artists and institutions such as publishers, retailers, libraries, art schools, and festivals.

When we write the history of the arts, we often focus only on the genius of individual artists and their artworks. The romantic myth of the genius, isolated artists, states that they have a special vision to see through the mere norms of our society, and therefore, cannot be bound to live by these norms.

However, just like anyone and anything else in our society, arts and artists are embedded in their society. They do not stand apart from us.

The work in our hands did not magically emerge from a vacuum. Instead, it is the result of many subjective choices and conventions created by mediators involved in its production and distribution. Artists and artworks need to be chosen by editors at publishing houses with limited resources and their own biased tastes and value systems. Distributors only carry works produced by well-known publishers that have a spine and meet certain page requirements. This is why I said, “Publishing is an act of writing a history.” Retailers and librarians purchase only a small part of such works. Retailers differentiate the way to display works based on their guesswork of salability. Zine/book fairs present tabling artists who are only a portion of applicants because the space and resources are limited. You choose the specific work to spend your time with, not other works besides them, maybe because you heard good reviews from critics. The specific media you gave attention to decided to disseminate the voice of the specific critics.

At each stage of production and distribution, these mediators serve as subjective filters, shaping the work and its reception according to their own perspectives and biases. In a small artistic field like independent comics, artists sometimes operate as mediators too. Mediators assert their authority as tastemakers by consecrating and canonizing certain works, despite the innate subjectivity of any “artistic criteria”. We need to ask who gets to write the history of comics.

Any artwork is the result of collaboration between the artists and mediators, as well as among artists, even when such collaborations are not explicitly acknowledged or realized. An artist is often part of a network/community of artists that share artistic vision, knowledge, and know-how; provide continuous and constructive feedback to one another as artists and audiences; and offer artistic as well as social and emotional support. This collaboration/network/community could be realized in various modes: peer-centered group, a mentor-mentee relationship, even a social media following, etc. Such networks, which blend the dynamics of a friendship and work groups, have played a vital role in building artistic movements throughout the history of modern art such as Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, Minimalism, Photorealism, etc., as well as the history of comics, most famously San Francisco’s Underground Comics.

However, in comics histor(iograph)y, the subjective and networked nature of production, distribution, and reception has been ignored. Moreover, it has been written by the few who are also often objects of it, conflating their intentions and interpretations.

These artistic networks of artists and mediators are one of the important reasons that Canadian independent comics kept their distinctiveness and sustainability. Often mediators like The Beguiling, Weird Things, Toutoune Gallery, TCAF, Zine Dream, Ontario College of Arts and Design (OCAD), Toronto Public Library, Toronto Zine Library, Canada Comics Open Library, Koyama Press, Conundrum Press, and Colour Code, operate as a space for artistic networks to form and flourish. Like in any other art form, each network appears, changes, and disappears constantly. What is important is to sustain a healthy field so that new networks emerge and remain productive and innovative.

“Post Internet Toronto” Exhibition and the Accompanying Interview Series

I curated a small “exhibition”, “Post-Internet Toronto”, at Toutoune Gallery (with support from Arts Council Korea) as a form of “public open library” to demonstrate how such networks operate in practice in Toronto, especially of the last decade. I refer to this period as “Post-Internet” (interchangeable with Post-Digital in some literature), as it coincides with the mainstream adoption of smartphones and social media.

(The inspiration for the exhibition came from the Futures of Comics programme directed by Ilan Manouach at the Fumetto International Comics Festival 2019 in Luzern, Switzerland. As part of the programme, I curated a Canada-themed exhibition and talks.)

Why focus on the last decade? It was during this time that Toronto’s independent comics networks flourished the most in the history of North American independent comics. The beginning of annual TCAF and Wowee Zonk Room; establishment of Koyama Press and associated artists; legitimization of comics in institutions like Toronto Public Library, which hosts TCAF, and universities including OCAD; the growth of the risograph, initiated by Colour Code; etc.

To complement the exhibition, I have been conducting interviews with people who are part of Toronto independent comics networks. I will release these interviews online in comics-related spaces throughout the year.

Additionally, through the interviews, I investigated whether the networks are sustainable despite the rising cost of living and steep increases in rents in today’s Toronto, as well as the fragile nature of independent comics’ artistic networks that depend on very few people.

The comics featured are mostly lent from The Beguiling, the Canada Comics Open Library, and Toutoune Gallery to underline the roles they play in the network. List of works featured are at the bottom of the essay.

Why “Post-Internet”?

– The Dialectics of Technology and Visual Culture in Post-Internet Comics

[Reminder: I refer to the period since the last decade as “Post-Internet” (interchangeable with “Post-Digital”), as it coincides with the mainstream adoption of smartphones and social media.]

The second goal of the small exhibition is to explore the dialectics of technology and visual culture through Post-Internet comics, which has been a focus of my critical practice.

I have argued that comics are the quintessential Post-Internet media and studied how Post-Internet aesthetics are negotiated in comics through new genres such as Navigating Space Comics, Structural Comics, Deskilled Comics (including memes), Conceptual Comics, and Comics of Affect (Materiality and Embodiment).

In addition, I have touched upon the dialectics of technology and visual culture via Comics/Collage/Appropriation.

Last but not least, the revival of feminism in the late 10s (sometimes referred to as “fourth wave feminism,” although I do not prefer the wave metaphor), which unfortunately faces the backlash at present, was partly thanks to the surge of social media. The new South Korean feminism, in particular, inspired me not only to notice the patriarchy and misogynistic bias in every aspect of our society, including each stage of production, distribution, and reception of the arts, but also to question the subjectivity of canonization and history writing and the romantic myth of isolated genius.

The following are summaries and updates of the relevant arguments and concepts that I have discussed, along with some examples of works featured in the exhibition.

- Comics are the quintessential Post-Internet media:

from instagram @freeze_magazine

“Comics are the preeminent element of contemporary post-digital visual culture. The epitome of post-digital culture, Meme, proves this. Meme is a comic: it has words and pictures working together, often literally depicting a character and what it says; sometimes it has a sequence of images; sometimes it is actually a comic. … Meme is vernacular: it does not have authorship and it is made and enjoyed by the masses. … [I]n the post-digital age, comics have become the language of mass culture. People speak in comics (emojis and memes), not in words alone, on their smartphone.”

- “Comics are the Language of the Post-Digital Age” (2019) LAAB #4.

“The language of contemporary society is comics: we talk online with memes and emojis. The most popular social media platforms — Instagram[ and] Tiktok — are comics (Tiktok is comics-video).”

- “Best Comics of the Decade” (2020) Solrad.

- Navigating Space Comics:

Navigating Space Comics narrates by spatializing.

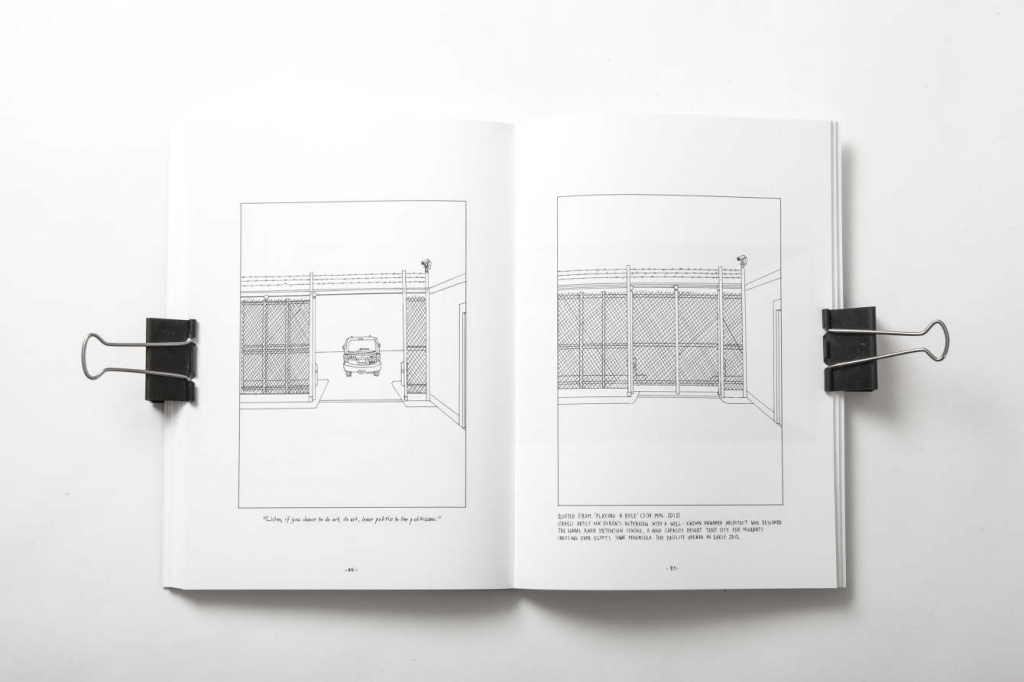

Undocumented by Tings Chak

“Navigating Space Comics … are interested in exploring space instead of characters, emotions, or plot development. For Navigating Space Comics, space itself is a topic, subject, or motive, more than a background or environment. The narrative is the sum of interactions with space. The narrative propagates as characters navigate spaces, not as characters/emotions/plots evolve. … How Navigating Space Comics Work: Spatializing by Navigating …

[According to Manovich’s The Language of the New Media (2001),] the new media [i.e., computer] is a navigable space. We had already been familiar with navigable space through video games and computers. However, with the growth of the smartphone, now our minds ([but] not our actual bodies) explore navigable space 24/7. … It might seem quite paradoxical that one of the most technology-influenced genres, Navigating Space Comics, is poetic. These works compel the reader to take time to ponder meaning, and are proponents of walking, going out, looking around us, instead of staring into what we hold in our hands. … We [create and] read these comics to get away from the suffocating but inescapable smartphone landscape that we participate in.”

- “Navigating Space Comics: An Introduction” (2021) Solrad.

I wonder if “Navigating Space Comics” is too much of a mouthful? What about “Navigating Comics” or “Spatializing Comics”?

Examples: Works by Patrick Kyle, Marc Bell, Kai Lumbang, Eli Howey, and Martin Vaughn-James; Undocumented (2014) by Tings Chak, Perish Plains Vol.3 (2015) by Seth Scriver & Keith Jones, and Panorameye (2016) by Michael Comeau and Mark Connery

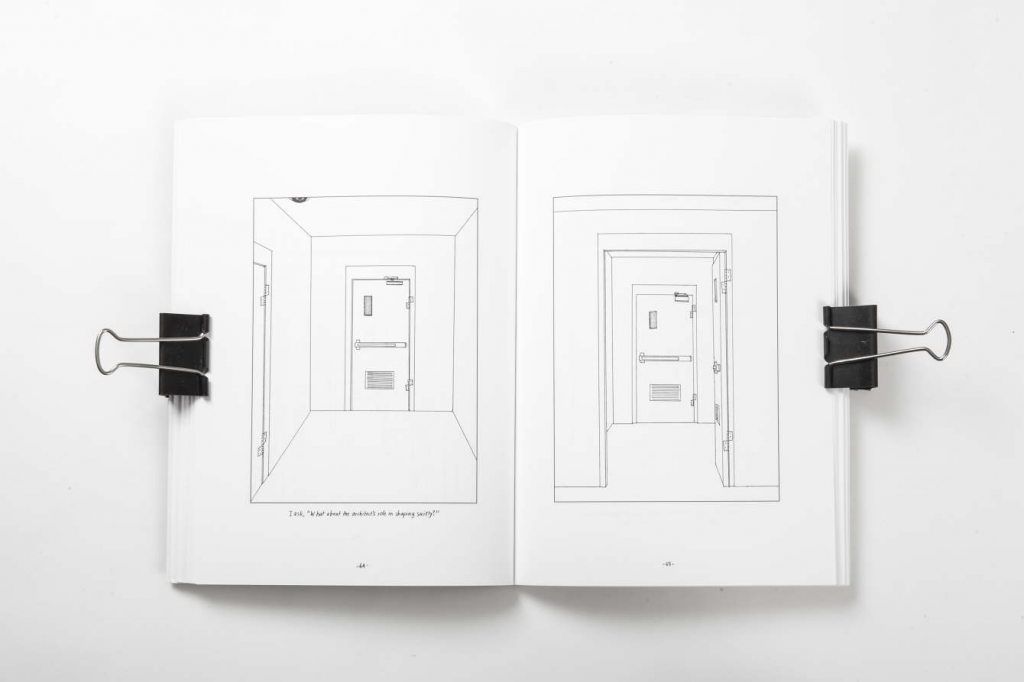

- Structural Comics:

Structural: à la Structural Films like Toronto’s own Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967) and La Région Centrale (1971).

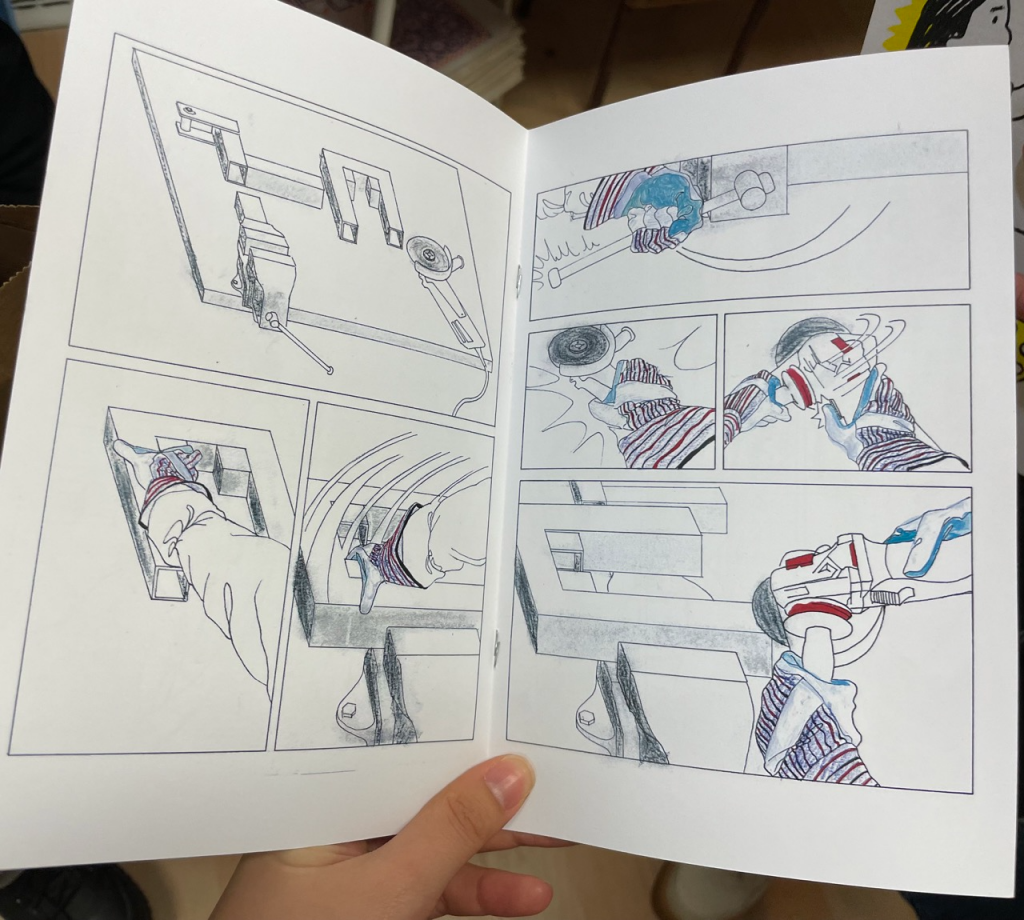

Table Vise by Evi Tampold

In the essay that introduced the genre, I also used the term “Abstract Formalist Comics.” However, due to confusion caused by the word “abstract” (which I meant in the sense of narrative, but which some people interpreted as referring to style), I will now use the term “Structural Comics” exclusively.

“What they show instead is more of a “process.” … lack of narrative and words lead the reader to focus on the formal qualities and abstract concepts of comics … such as space-time, movement, body, … texture, representation, … repetition/difference, etc. … They are “Abstract” Formalist comics not because they do not show representational images — they do, and this is a critical difference between them and Abstract Comics — but because they show abstract narrative and study abstract and formalist … concepts[.]”

- “French Abstract Formalist Comics (French Structural Comics)” (2018) The Comics Journal.

I am planning to release an essay tentatively titled “Afterthoughts on Structural Comics” that will address several issues and misconceptions (held by both others and myself) from my previous essay. These will include the different desires and tensions between critics and artists, as well as dropping the “French” from the term.

In addition, many Structural Comics are Navigating Space Comics. Their processes can be read as (a process) of navigating space.

Examples: Works by Kai Lumbang; and The Ladder is Out of Reach (2021) by Patrick Kyle and Table Vise (2023) by Evi Tampold

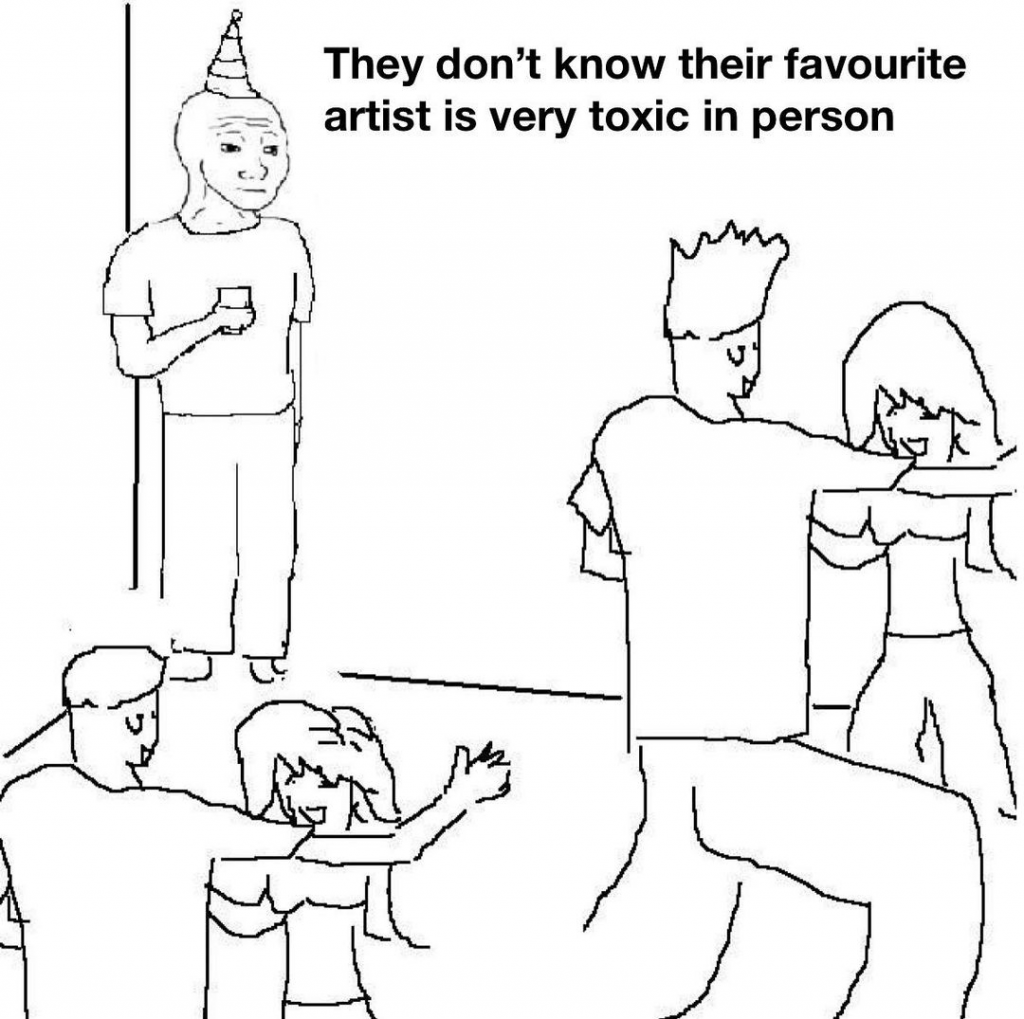

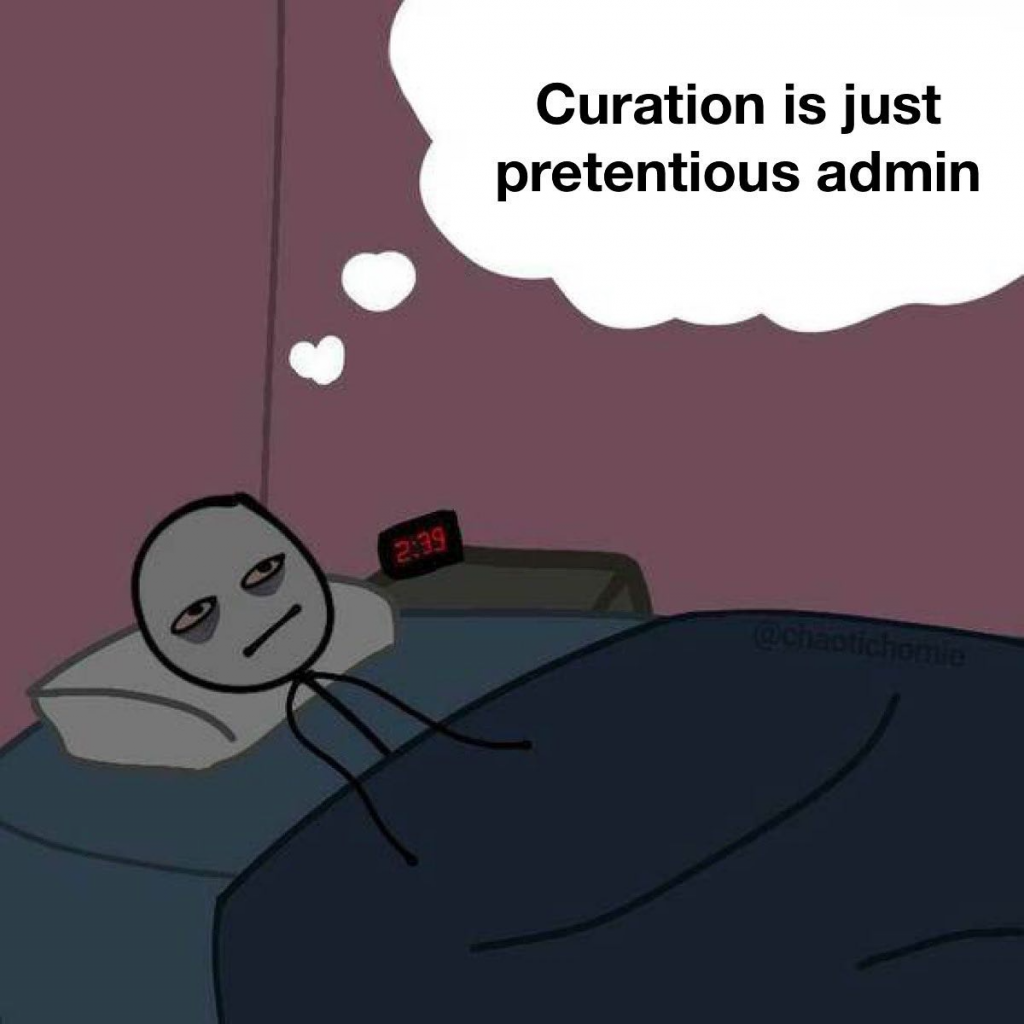

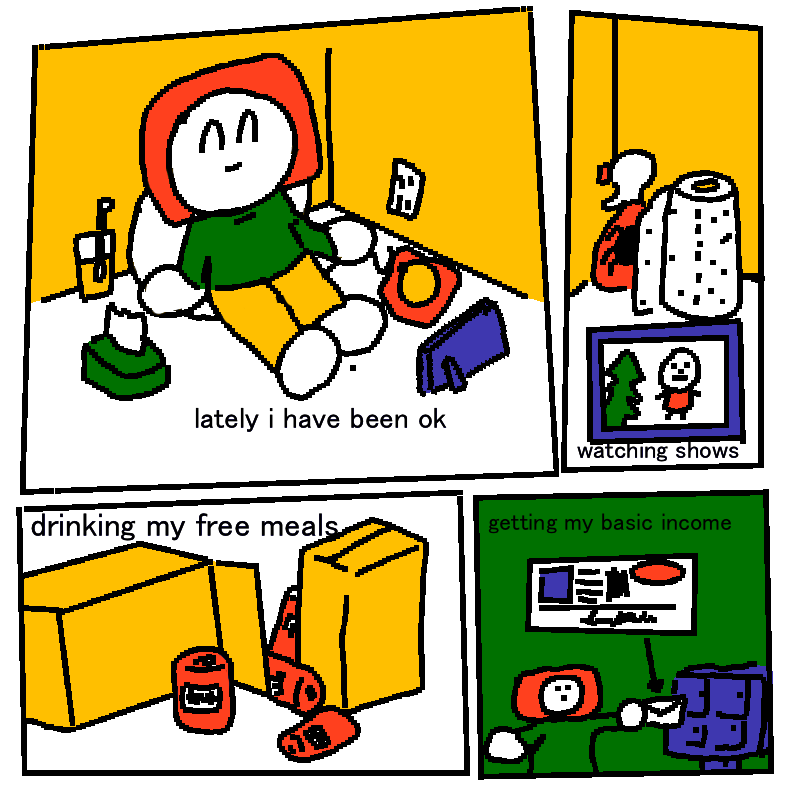

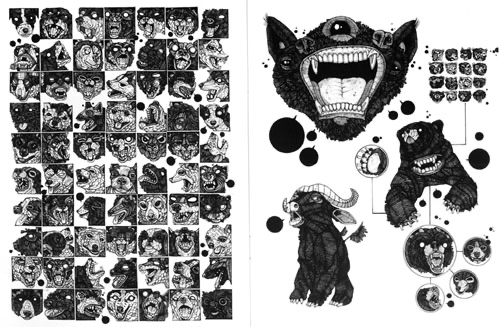

- Deskilled Comics (including memes):

Comics that are intentionally drawn in an ugly, poor, less-skilled, amateurish, glitchy, pixelized, or lo-fi way.

C2-Cat Comic by Mushbuh

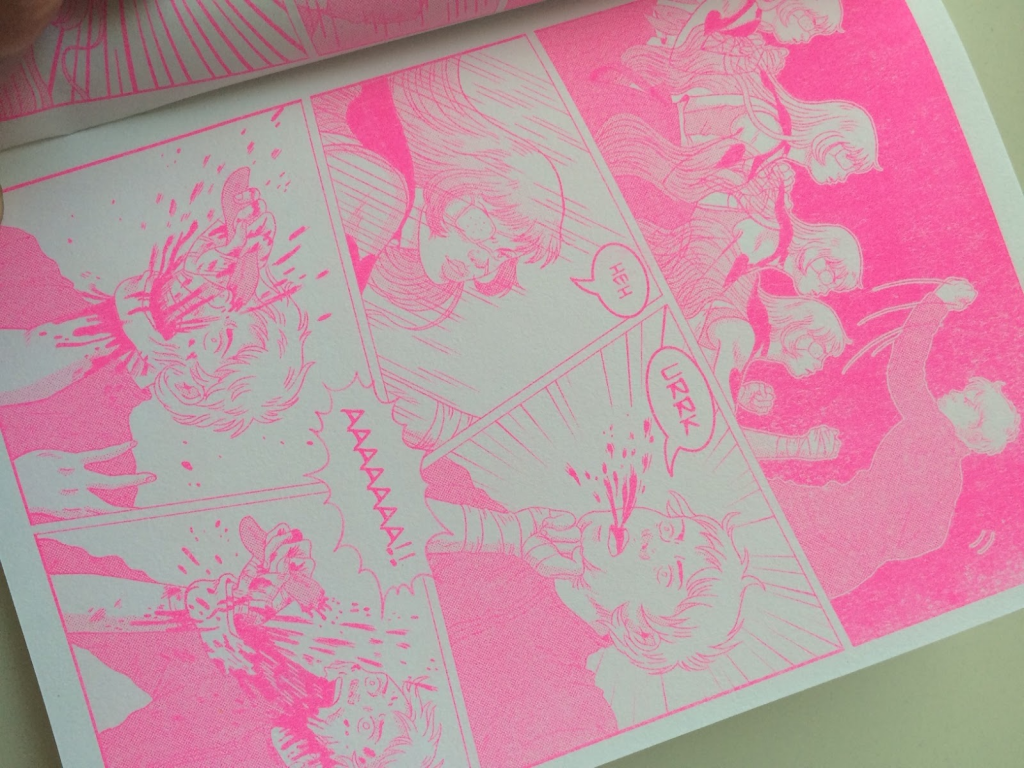

“In a post-[internet] surveillance society where advanced technology is omnipresent, omniscient, and omnipotent, the appreciation of technical limitation — glitches, pixelation, primary colors, and compression — is seen as edgy compared to the “mainstream” clean high-resolution photoshopped images like those found on “lame” Pinterest. The romanticization of lo-fi imperfection of post-digital manifests in physical objects too: the revival of LPs, cassettes, VHS, film cameras, mechanical typewriters, and Risograph.”

“The crux of Post-[Internet] aesthetics is the nostalgic affection for analog and physical media of yesteryear, rather than the mainstream aesthetic of advanced high-definition digital technology. Risograph, the most prominent method of contemporary comics and zine making, is the exemplar Post-[Internet] media: it is an old technology being revived out of nostalgia rather than technological superiority. Imperfections — including ink grains and misaligned color plates — are some of its charms.”

Examples: Works by Mushbuh, Kendra Yee, Michael Comeau (Digital/analogue nostalgia, especially in Texture), and Alexander Laird (Digital nostalgia); and MICK’S Spiralling and Enigmatic Mystery (2023) by Varvara Nedilska & Agnes Wong (Digital nostalgia).

- Conceptual Comics:

From Conceptual Art.

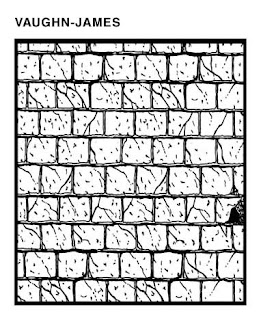

BrickBrickBrick by Mark Laliberte

Some art historians contend that the emergence of conceptual art in the 1970s is related to the contemporary rise of the computer.

Also see: “Conceptual Comics of Ilan Manouach” (2019) and “Conceptual Comics of Stefanie Leinhos.” (2019)

Examples: Easy (2014) by Kawai Shen, The Latter is Out of Reach (2021) by Patrick Kyle, and BrickBrickBrick (2010) by Mark Laliberte,

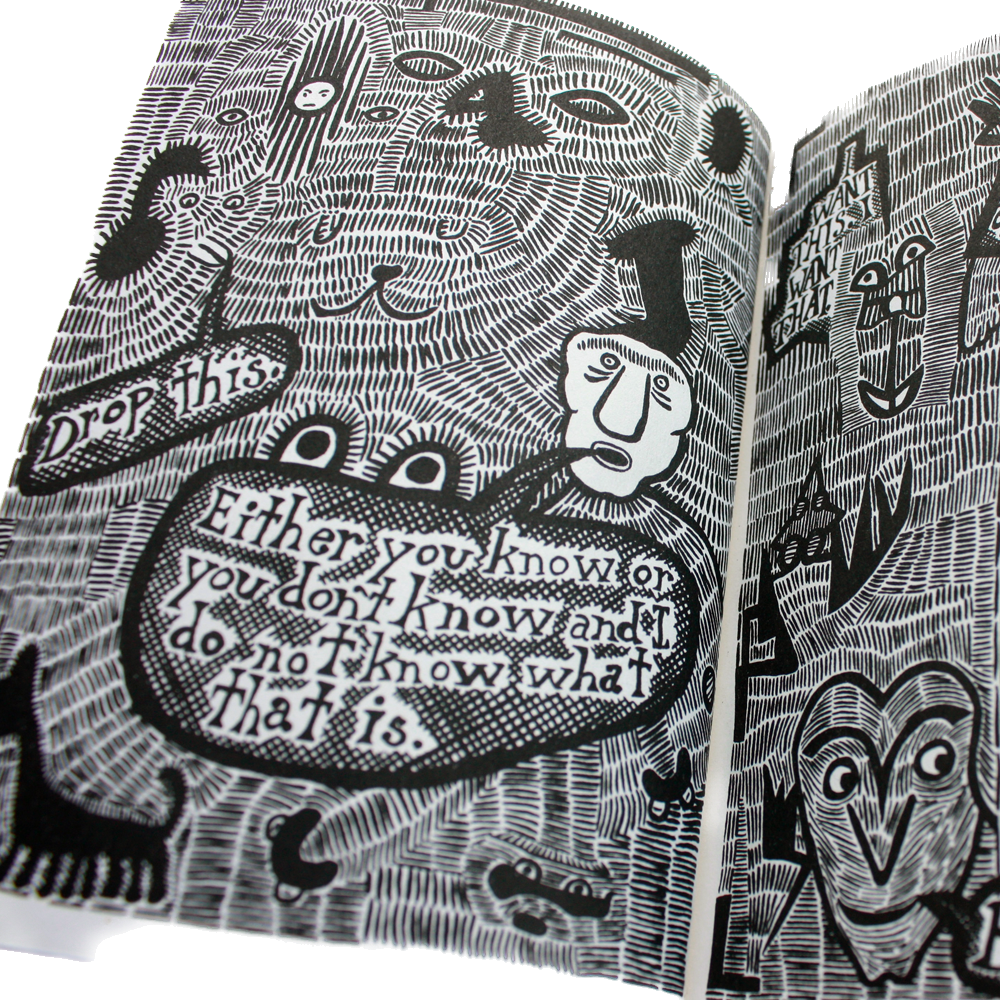

- Materiality (of Comics and Comics of Materiality):

Bubies by Ginette Lapalme

“[According to Laura Marks’ The Skin of the Film (2000), inspired by Deleuze,] haptic visuality emphasizes the texture and materiality of the image rather than the meaning of the object of the image. … [In such comics,] the reader can see the touch of the brush, the motion of the paint as it disperses on the image, and the texture and materiality of the image on the page. We perceive marks of the artist’s touch. We feel the artist’s tactile presence.

… To appreciate [Riso’s] distinct saturated color schemes, you need to hold it in your hands, for PDFs do not do it justice. When seeing the intense hues and feeling its grain and texture, reading a Risograph zine becomes an immensely tactile experience.

We go back to the past because our imaginations have already materialized IRL and been exhausted. Reality is faster than our imagination. The future is the present; omnipresent and omnipotent technologies embedded in our bodies metamorphose us into cyborgs of voluntary surveillance. In the Post [Internet] age, we want to touch real objects, not merely screens. We long for the physicality of actual things. The more time we spend in the virtual world, the more we become nostalgic for the actual world. As we infinitely scroll the conspiracy theories of the world, we get lost in both our world (time and space) and ourselves. Who am I when Google and Facebook know more about me than I do?

… The haptic visuality … becomes a way to negotiate or fight against the omnipresence of digital media. …

Comics are a great medium to employ haptic visuality — or any other sensual visuality, for that matter — because no other visual medium allows the viewer to touch the art. Comics are democratic and cheap. The viewer is not distanced from the art but encouraged to come close and hold the art. We can smell the comic. (After purchasing the comic inexpensively, you can even taste the art, if you insist.) / When there is no distinction between the actual and virtual; when nothing is certain, even the existence of the future — or the present — comics become the lingua franca. Can comics save the world?”

- “Comics of the Senses …” (2021)

Also see: “The Materiality of Comics in the Post-Digital Age: Comics of CF and Ginette Lapalme” (2019) / “Vincent Fortemps’ Comics Sculptures” (2019) / “The Question of the Visual: Ilan Manouach’s Shapereader” (2019) / “Sammy Stein on the Art/ifacts of the Real and the Virtual” (2018)

Examples: Works by Marta Chudolinska, Ginette Lapalme, Eli Howey, and Jon Inaki, and Sabrina Scroll Fanzine (2023) by Jordan Reg. Aelick

- Texture in Comics

A related concept I had intended to discuss in “The Materiality of Comics: Alexis Beauclair, Erin Curry, and Warren Craghead” (2019) was the “texture” of the comics page or the depicted space in comics.

Isolated Comments by Jonathan Peterson

Examples: Works by Jonathan Peterson, Nina Bunjevac, and Michael Comeau; and Leaving Richard’s Valley (2019) by Michael DeForge

- Comics of Affect* and Embodiment

Condo Heartbreak Disco by Eric Kostiuk Williams

“Happy Days” from The Pleasure of the Text by Sami Alwani

Martine Beugnet of Cinema and Sensation (2007) argued that “in its flaunting of the corporeality in all its visceral presence … extreme cinema [of Claire Denis, Catherine Breillat, etc. ] offers itself as the counterpoint to digital postproduction’s perfected female body, a reminder of the existence of actual sentient gendered bodies beyond the dematerialized of digital imaging and communication.” Comics of Affect* and Embodiment operate in similar fashion.

“We go back to the past because our imaginations have already materialized IRL and been exhausted. Reality is faster than our imagination. The future is the present; omnipresent and omnipotent technologies embedded in our bodies metamorphose us into cyborgs of voluntary surveillance. In the Post [Internet] age, we want to touch real objects, not merely screens. We long for the physicality of actual things. The more time we spend in the virtual world, the more we become nostalgic for the actual world. As we infinitely scroll the conspiracy theories of the world, we get lost in both our world (time and space) and ourselves. Who am I when Google and Facebook know more about me than I do?

… [Comics of Affect* and Embodiment] inherently emphasize the dialectics of the bodily and the dissociated.”

* affect: “[According to Massumi, paraphrasing Deleuze,] affect is a primary and unconscious feeling or atmosphere that we sense, but cannot cognize. It is the thing before the emotion. Affect is ambivalent and nameless, while emotions have names[.] … Affect is [not] recognizable while emotion is. Affect is a potential where contradictory things can co-exist. Emotion is actual, while “affects are virtual synaesthetic perspectives anchored in (functionally limited by) the actually existing, particular things that embody them.”

- “Comics of the Senses …” (2021)

Also see “Affect of Overload in Contemporary Women’s Comics.” (2020)

Examples: Works by Nina Bunjevac, Marc Bell, Eli Howey, Michael DeForge, Fiona Smyth, Sab Meynert, Jillian Tamaki, Sami Alwani, and Eric Kostiuk Williams.

- More Deskilled Comics:

These concepts of affect and haptic visuality also explain why Deskilled Comics, including memes, rose to prominence in the Post-Internet age, in addition to technological reasons such as “the democratization of image processing thanks to the exponential advance of both software and hardware; the evolution of internet communities into social media, which requires fast uploading and responding; and the smartphone, which enabled instant access to social media from everywhere and at any time.“

Deskilled comics are simultaneously cute, repulsive, humorous, ugly, affective, and horrific. This co-existence of the contradictory, which creates ambivalence, unrecognizability, and namelessness, is the essence of affect. Additionally, Deskilled comics’ irony and detachment displayed via intentionally ugly and amateurish art, i.e., haptic visuality, prompt us to recognize the artist’s touch and presence.

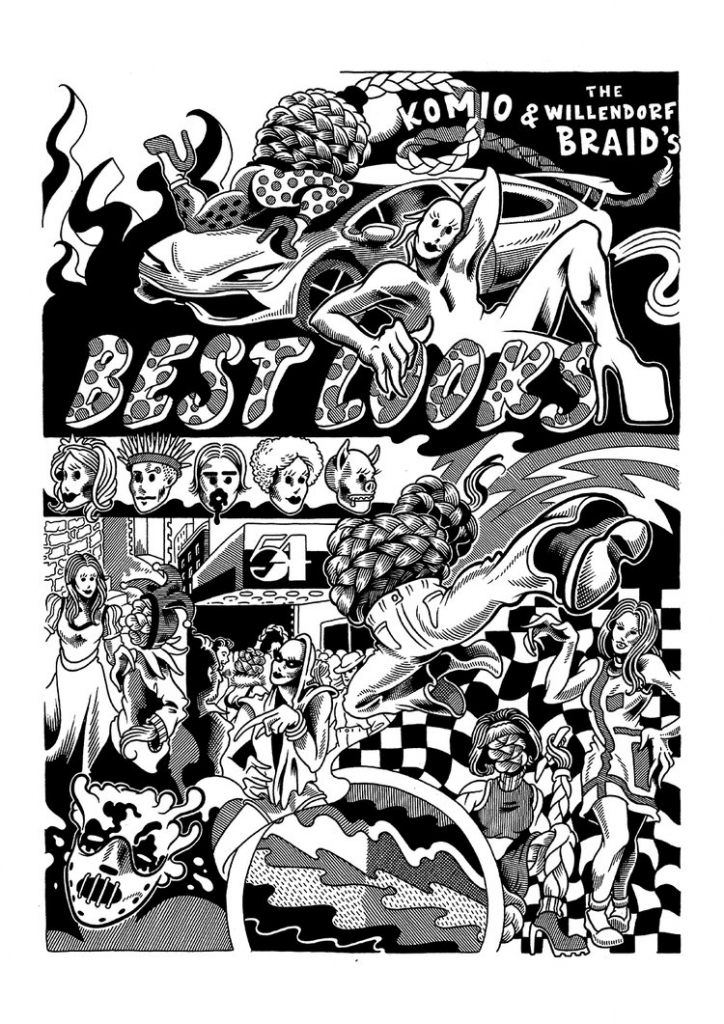

- The dialectics of technology and visual culture via Comics/Collage/Appropriation:

Wunderkammer Nº 1 by Nicholas Di Genova

Magical Beatdown by Jenn Woodall

“Comics and collage are homologous. Both are discrete, discontinuous, heterogeneous, and modular. Comics are collages of panels/images (and often words). …

Artists with an appreciation for comics have been fascinated by this interconnection, such as Jess, Joe Brainard, Öyvind Fahlström, Guy Debord, Situationist International, Isidore Isou (and fellow Letterists), Keiichi Tanaami, and Bazooka Collectif (which created influential collage art for both the newspaper Liberation and comics magazines like Hara-Kiri in the ’70s). …

Comics and collage both operate in two layers: surface appearance ([the entire work or] page) and the underlying source (panel). … Guy Debord’s explanation of collage in A User’s Guide to Détournement – “When two objects are brought together, no matter how far apart from their original contexts may be, a relationship is always formed.” – applies to comics perfectly.

The image inside a panel is also a collage. Bold lines distinguish every object from one another, especially the character and background. Comics’ flatness, modularity, discontinuity, and heterogeneity differentiate them from the continuous spacetime of contemporaneous visual media such as photography and cinema – and their great ancestor, traditional European paintings. The latter yearns for illusion and simulation of the real world, but comics are inherently representational. The latter lives in coherent continuous spacetime with a single definitive perspective, but comics are innately discrete.

These two levels of discreteness, modularity, heterogeneity, discontinuity, and flatness demonstrate why comics are the medium well suited to collage/appropriation.

The maturation of newspaper strips occurred concurrently with the Dadaist and Surrealist collages like Max Ernst – whose work has been incorporated into the comics canon (e.g. included in 1001 Comics You Must Read…) – and Cubist and Futurist paintings. They were all part of the Modernist movement that rebelled against the European visual arts tradition of the single definitive perspective and continuous spacetime. It is no coincidence that Pablo Picasso created one of the first graphic novels Sueño y mentira de Franco [Dream and Lie of Franco] in 1937.

Mass reproduction was another important development that made both collage and comics possible. It is critical that comics were created in the pages of newspapers. Newspapers juxtapose stories in different spacetimes on a page. They necessarily have a modular design to carry these different stories. Grids come from this modular design, and might have influenced the panel-centric form of comics. The heterogeneous combination of words and images also follows from the newspaper graphic design. “

- “Comics / Collage / Appropriation” (2021) The Comics Journal

The essay also mentions some works included in the exhibition and demonstrates how these works deploy collage/appropriation.

Examples: Works by Marc Bell, Mark Laliberte, Michael Comeau, Ginette Lapalme, and Jon Inaki; Leaving Richard’s Valley (2019) by Michael DeForge, Easy (2017) by Kawai Shen, Wunderkammer Nº 1 (2009) by Nicholas Di Genova, MICK’S Spiralling and Enigmatic Mystery (2023) by Varvara Nedilska & Agnes Wong, and Magical Beatdown (2015–) by Jenn Woodall.

Finally, I have written about several works featured in the exhibition in “Best Comics of the Decade” (2020), which was partly a polemic against the current histor(iograph)y of comics, and “Best of the Decade: Canadian Comix” (2020).

List of Comics Featured (Some works might not be present at the exhibition)

- Canadian Comics Anthologies: Nog a Dod (ed. Marc Bell, 2006), Ganzfeld #5: Japanada (2007), and This is Serious: Canadian Indie Comics (ed. Alana Traficante & Joe Ollman, Conundrum, 2019)

- Ahmed, Misbah: 5 Minutes in Karachi (Old Growth, 2019)

- Aelick, Jordan Reg.: Sabrina Scoll Fanzine (2023)

- Alwani, Sami: The Pleasure of the Text (Conundrum Press 2021)

- Beaton, Kate: Ducks (D&Q, 2022) and Hark! A Vagrant (D&Q, 2011)

- Bell, Marc: Hot Potatoe (D&Q, 2009)

- Bunjavic, Nina: Heartless (Conundrum, 2012)

- Carrasso, Freddy: Hot Summer Night (BDP, 2017), Gleem (2019)

- Chak, Tings: Undocumented (Ad Astra, 2014)

- Chudolinska, Marta: Babcia (2018)

- Chouck, D.: Canada Made You Trans (2019)

- Comeau, Michael: Hellberta (Colour Code, 2015), Winter’s Cosmos (Koyama, 2018), and Tool of Perception Sketchbook (2007)

- Connery, Mark: Rudy (ed. Marc Bell, 2014)

- Connery & Comeau: Panorameye (2016)

- Dairy Sam: Flower Week (2020), Last Chances (2021), My Big Bright Love (2021), Did You Ever Eat a God (2022), Some Sacrifices (2022), Clapping lenticular (2022), and I Love Being Ugly and Fat (2023)

- DeForge, Michael: Posters, Very Casual (Koyama, 2013), Leaving Richard’s Valley (D&Q, 2019), Familiar Face (D&Q, 2020), and Birds of Maine (D&Q, 2022)

Cf. Loving Richard’s Valley (2018): anthology fanzine of Leaving Richard’s Valley

- Ed. Deforge & Koyama, Annie: Root Rot (Koyama, 2011)

- Diamant, Rotem: Toronto Renting Adventures (2018)

- Di Genova, Nicholas: Wunderkammer Nº 1 (Koyama, 2009)

- Harris, Jesse: IDYEAHS Disposable Bag (Colour Code, 2013)

- Howey, Eli: Fluorescent Mud (2018) and Passageways (2020)

- Inaki, Jon: Yukon Ghost (2014), On Sneaking (2020), and Brainerd St.Cloud (2023)

- Jordan, Jessi: Vanilla White #1-2 (Swimmers Group, 2012-3)

- Kyle, Patrick: Distance Mover (Koyama, 2014), Don’t Come in Here (Koyama, 2016), Roaming Foliage (Koyama, 2018), The First Floor (2021), and The Ladder is Out of Reach (2021)

- Kyle, Deforge, & Mickey Zacchilli: Jumping Comic #1 (2014)

- Laliberte, Mark: BrickBrickBrick (Book*hug, 2010)

- Laplame, Ginette: Pin Up Girls series (2007-9), Miniature Zine Combo (2011), Confetti (Koyama, 2015), My Stamps Collection zine, poster, & stamps (2019), Climb-ing Mushrooms Fabric Zine (2019), Sketchbook zine (Colour Code, 2019), and Dalle-2 stickers & objects (2023)

- Lapalme, Connery, & Zuzu Knew: Meow Means Hi (2014)

- Ed. Wowee Zonk (Lapalme, Kyle, & Kuzma, Chris): Wowee Zonk #4 (Koyama, 2012)

- Laird, Alexander: Guaranteed Spooky Stories (2022)

- Lim, Elisha: 100 Crushes (Koyama, 2015)

- Lowe, Jamiyla: Good Evening (2018) and As You Wish (2020)

- Lumbang, Kai: All Boys Leave Home (2019), Madrigals ov the Tose Angel (2019), No Health (2019), Celestial Summons (2019), The End Comes Beyond Chaos (2020) and Omega Blade Eternal (2021)

- MacKinnon, Mark G: Adapted Remnant Groudslab Transfer Drawings 2009-2015 (2015)

- Mark, Natalie: From Yesterday (Old Growth, 2019)

- Martins, Victor: Hey, I don’t Mean to Be Condescending… (2018)

- Meynert, Sab: Sprawling Heart (2016)

- Moritz, Blaise: Thousand Oaks: Machine Mail (2022)

- Mushbuh: 310,310 (2017) and 978-91-87435-43-4 (2019)

- Nishio, Robin: Wailed (Koyama, 2015)

- Nedilska, Varvara & Wong, Agnes: MICK’s Spiralling and Enigmatic Mystery (Colour Code, 2023)

- Petersen, Jonathan: Isolated Comments (Colour Code, 2017)

- Scriver, Seth: Stooge Pile (D&Q, 2010) and Blob Top Magazine #1-2 (Colour Code, 2015)

- Scriver & Keith Jones: Perish Plains Vol.3 (2015)

- Shen, Kawai: Interview with Peter B (2016), Easy (2017), and “This is Not a Review of Kate Beaton’s Ducks” (2023)

- Smyth, Fiona: Somnambulance (Koyama, 2018)

- Smyth and Cory Silverberg: You Know, Sex (2022)

- Spector, Shira: Red Rock Baby Candy (2021)

- Tamaki, Jillian: Indoor Voice (D&Q, 2010), SuperMutant Magic Academy (D&Q, 2015), Boundless (D&Q, 2015), They Say Blue (Groundwood, 2018), and Our Little Kitchen (2020)

- Tamaki & Tamaki, Mariko: Roaming (D&Q, 2023)

- Tampold, Evi: Table Vise (2023)

- Vaughn-James, Martin: The Projector/Elephant (1970/2022) and The Cage (Coach House, 1975/2013)

- Williams, Eric Kostiuk: Hungry Bottom Comics (2014), Condo Heartbreak Disco (Koyama, 2017), and 2AM Eternal (2023)

- Woodal, Jenn: Magical Beatdown #1-3 (2015 -)

- Xu, Lis: Jungle Book (2019), I Had a Dream That We Ran Away From Home (2019), and WYD (2020)

- Yee, Kendra: yes oh no (2014), 1,2,3,4,5,6,6 (2014)

Publishers:

- Koyama Press: What is Obscenity? (2017) By Rokudenashiko, After Nothing Comes (2016) by Aidan Koch, Hot or Not: 20th-Century Male Artists (2016) by Jessica Campbell, Anti-Gone (2017) by Conor Wilumsen, and Space Academy 123 (2018) by Mickey Zacchilli

- Colour Code: Zines 2016 – ) by Tetsunori Tawaraya, His Story of War (2017) by Gunsho, and Dogs in a Pile (2019) by Ben Clarck

- Ad Astra: War in the Neighborhood (1999/2016) by Seth Tobocman

- PopNoir: The Noiseless Din (2021) by Scott Carruthers

// kim jooha is a comics critic and editor based between Toronto and Seoul. kimjooha.space is her website.

// The exhibition and my visit are supported by Arts Council Korea.

// I want to thank Ginette Lapalme, Ilan Manouach, the Omidvar-Khullar family, artists who lent their works, editors she has worked with, Arts Council Korea, The Beguiling, The Canada Comics Open Library,Toutoune Gallery, and Toronto’s independent comics community.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply