Usually, when I sit down to read a graphic novel I’m planning to review, I have a legal pad beside me so I can take notes to refer back to as I begin writing. I did that with Keeping Two, Jordan Crane’s new graphic novel. However, when I finished the book, I looked at the pad and realized I hadn’t made a single note. That’s not because there wasn’t anything noteworthy about Crane’s work; instead, it was because I was so engrossed in the story he tells.

I should say the two stories he tells, as there are two narratives that run through much of the work. It takes a while to understand how the secondary narrative connects to the first, though the why is pretty evident early on. The main reason for the confusion is that Crane moves back and forth from one narrative to the other with no real transitions to speak of. Also, the primary narrative starts in the middle of Will and Connie’s story, then flashes back and forth between their past, present, and various imagined futures.

Both narratives are about a heterosexual relationship that is clearly struggling; that struggle is made worse through a death or the possibility of a death. In the secondary narrative, the man has gone to a conference while his wife is pregnant, and he returns just as she is giving birth. Unfortunately, the baby does not survive, and they spend the rest of their narrative dealing with their guilt and accusations. Crane doesn’t complete this narrative for us or for the characters in the main story; how each person interprets that part of the work is part of Crane’s point.

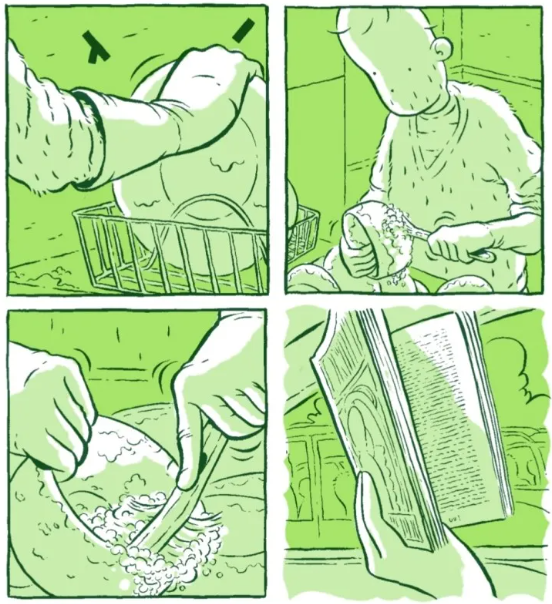

In the main story, Will and Connie have returned from a trip where they have fought about each other’s driving. When they return, Will checks his messages—the time frame is unclear; they still have a landline, but Connie also has a cell phone, so it could be the early 2000s—to find that a friend’s roommate’s brother has died at 23 of leukemia and Will’s mother’s dog has died. These deaths and the second storyline cause both Will and Connie to consider their partner’s death.

Will thinks about deaths coming in threes, which makes him wonder who or what could die next. He says, “Lucky we only got two calls tonight! Creee-py. And what about the rule of threes? Don’t people die in groups of three?” Connie tries to dismiss this type of thinking, pointing out that his mother’s dog isn’t a person and such thinking is nothing more than superstition. Once this thought is in his head, though, it colors the way Will views the rest of the evening. Connie goes to the video store and the grocery store, but she takes a long time to return. The longer she is gone, the more he worries she has died.

He spends the middle part of the book imagining scenarios that could have happened, none of which are positive. He calls the video store, only to find out she left an hour ago. He calls the grocery store he assumes she went to and has them page her, but she isn’t there either. He then expands his scenarios to include how he would react if one of her imagined deaths was, in fact, true, leading to his life falling apart. He becomes so immersed in his imagination that he leaves the house to go look for her, even though he knows he shouldn’t.

Not surprisingly, she returns home in his absence, only to find he has gone looking for her. She, too, now has to imagine life without Will, but her imagination leads her in a different direction, partly because of an event that occurs as she begins to look for him. Her concern and reaction leads to a nearly thirty-page abstract sequence that takes the reader nearly to the end of the book. As with the secondary storyline, the ending is left fairly open for the reader’s interpretation, though not as open.

This sequence is a substantial change in the artistic focus of the work, as Crane has been fairly realistic to this point, coloring everything in the work in green hues. Since his work focuses on the everyday aspect of living, especially when the characters imagine their lives without the other, he employs the typical comic sound effects of daily life, whether that’s the FUMP of a bag dropped on a couch or the ERK of a car braking. Crane also reminds the reader of the characters’ real and imagined losses through the outline of a body that follows them around in one way or another. In the secondary storyline, the woman carries the image of her baby with her wherever she goes, while in the main narrative, Will has an outline of Connie in the passenger seat as he is driving looking for her. The change in artistic style at the end could represent Will’s reaction to what has happened because he went to look for Connie, or it could represent a change in reality, in general. Again, Crane leaves this interpretation to the reader.

The work is engrossing not merely because the reader wonders what will happen to these characters and what decisions they will make about how to live with the recognition of the mortality of those they love, but also because the work’s open-ended nature encourages the reader to think about their own views on mortality and life. The overall idea of the book concerns our taking daily life for granted, as if it will always exist in the way it does, ignoring the reality that we and those around us are all mortal. As with all great literature, it forces us to think about our lives and how we wish to live. And there’s no way to take notes on that; we just have to experience it.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply