Tommi Musturi’s Future is a bright, urgent, and distinctive work on the self-published racks in my local comics retailer. Self-published through his own Boing Being brand, the Finnish artist’s latest work is an anthology, unraveling over ten issues, that started in 2018 and is being released twice yearly. Every installment is a breathless collection that encompasses scratchy painting, bubblegum digital coloring, a misanthropic magician, an aggressive speaking screen, and much more besides.

While the Finnish anthology series Kuti that Musturi is involved in features art by tons of artists per issue, Future’s bombastic array of styles and plots are authored solely by Musturi. He’s been busy in the Scandanavian comics scene since the mid-’90s. He was part of the curatorial team of the Helsinki Comics Festival, and in some circles he’s as famous, maybe even moreso, for making digital art under the pseudonym Electric. At one point, Boing Being also doubled up as a garage and punk rock label. There’s more Musturi content out there than is possible to summarise in a few brief paragraphs, which makes him a perfect candidate for comics fans obsessed with the singular and the self-published, though three book-length works of his are available in the States via Fantagraphics.

I caught up with Musturi in May 2020 to talk about his background in the demoscene, Future, old visions of the future that have inspired him and the influence of internet aesthetics over his work.

Nicholas Burman: In my mind, Finland is this very big landmass with very few people, so there is lots of space and opportunities to get lost or isolate, especially compared to the Netherlands or the UK where it’s pretty much impossible to not come across someone no matter where you are. Is that something you recognize, or does it perhaps only become noticeable if you travel to somewhere with a denser population?

Tommi Musturi: I’m originally from a small countryside village in the south-middle of Finland. Back then it had just thirty inhabitants and the closest grocery store was 10km away, so long distances are sort of natural for me. These distances just meant me and my friends biked 10–20km each day to see each other. We spent lots of time outdoors doing stuff in the forests and all that. I’d say the distances do not result in “isolation” but you finding different ways of doing things. So we did not just play with pine cones, but mail-ordered skateboards and found our own ways of doing stuff. That made us kids active and use our imagination.

I got involved with the demoscene at an early age, when I was around 9 years old I got my first home computer, the Commodore 64 (C64). Through that, I got in contact with lots of people all around Europe. We created our own small demos and swapped those by sending floppy discs via mail (this was before the internet). My friends did the code, some made music and some – like myself – made the graphics, then we’d spend a weekend at some summer house to put it all together and release it. At the age of 13, I was getting ten to twenty packages each week and sent the same amount abroad. We also sent each other mixtapes, mailart, comics, etc.

I started to become more of a music fan, and we started our first fanzines in junior high school. We constantly mail-ordered records and comics – whenever I found something interesting in some zine I wrote a letter to the author and sometimes ended up in correspondence with them for years. I also got into the ‘90s mailart scene (this was public domain art copied on paper or made into zines and sent via mail), and this is when I started to send my drawings around.

My friends and I got deeper and deeper into the scene and discovered this world of our own, often with material you could not really find anywhere in Finland. We mostly ordered records from the USA, Germany, and the UK. We’d find some advertisement, get the address, send a letter, and ask for a catalogue or “listing” of releases and order from that. We also started to release our own 7” records via a small label in the early 90s, mostly punk and noisy experimentalism.

Luckily, we had one of the best comics stores in Europe in the nearby city of Tampere called Kukunor. They imported stuff from all over the world, and stocked North American alternative comics from D&Q and Fantagraphics, as well as art comics from L’Association, Amok, and other European new wave publishers. So, even though I went there first to find new issues of 2000AD, I soon discovered all these weird releases. This store had a great impact on my generation of comic artists, everybody went there, and it was one of the main reasons why there was that first big boom of contemporary comics (or “art comics”) in Finland. They also held exhibitions and made a huge monthly mail order catalogue which even had reviews. This was something I read over and over again and usually made big orders a few times a year.

Despite the “isolation” of living far away from lots of things, I was pretty deep in the Finnish underground scene and pretty aware of things happening abroad as well. My friends traded movies via mail so I got all that stuff from them. I remember seeing John Waters films when I was about 15. They made a great impact and also gave a push to our efforts to make zines. We became friends with what some may call “trash.”

If you travel far east or north in Finland you may find things are different. There the population is even less, and (these days) have fewer services. However, social media has changed our society a lot and there are people moving to the countryside as well, as it’s possible to work remotely. You can find high-speed connections here almost anywhere. That makes the world smaller.

I notice I have a certain need for my own space, and alone time (as do most Finns, probably). Besides that, I don’t see so much difference. I have always had a strong inner world to spend time in.

I must admit that when living in this small village as a kid there were times when I dreamt of a 24hr gas station I could go to to buy some candy and play some arcade games.

NB: You’ve been involved in the Finnish comics scene since the mid-1990s, how’s it changed since then, and what’s your assessment of it right now? Are you in touch with other artists at this time?

TM: I went to art school in ’95 and that’s where I met other students who had been making their own “alternative” comics and zines for some time already. I wanted to try it as well and soon got more involved. That’s when I started to edit the anthology Glömp as well. In the end, that project lasted for twelve years and ten issues, ending up as a massive 300-plus page color publication distributed internationally.

There was a big movement in Finnish comics that took place at the same time, in the mid-90s, mostly in the art schools. As I mentioned, we had Kukunor. We also had some nice publishers and anthologies that published more artsy material, Suuri kurpitsa (The Great Pumpkin) was the most interesting of them. With these influences, the youngsters in the art schools soon started to try out different approaches to comic narration, experimenting with materials and equipment as well. I must stress that back in those days there was not really any comics studies course one could join, so everyone ended up doing it their own way. That was also something significant for the movement in Finland: the goal was to achieve our own style and method of narration rather than copying something from others. Of course, one can see influences from everywhere. but I still find that late 90s Finnish comics have their own looks and voices.

Every art school had a small collective of 5–10 people doing comics all the time, which led to 4–5 anthologies appearing on the scene. We already had two festivals taking place in Finland, both dating back to the ‘70s. These festivals were the natural place for artists to sell their work and meet artists from other schools, and also see the works and people from around the world. People from Stripburger, Le Dernier Cri, and some L’Association visited the Helsinki Comics Festival, while the Arctic Comics Festival in the far northern city of Kemi had great guests like R. Crumb and Moebius and tons of others, and a high-quality Nordic comics competition featuring lots of Scandinavian artists. There was healthy competition between the then-new Finnish anthologies Napa, Ubu, Vacuum, and Glömp; that competition meant that the zines started to already look really good, even better than commercial publications that have their roots in the mainstream. I, like a lot of the artists back then, studied graphic design. so we also had the tools to put it all together. Using Photoshop on Macs during the mid-90s was not really something that you could do back home as everything cost ten times more in those days. Thankfully, the schools were well equipped and we all took advantage of that.

When we reached the millennium, this new wave of artists started to graduate and we all had to ponder what to do in life. This is the moment when the people who were in their mid-twenties started to work on bigger books; graphic novels and all that. It was also the moment when Finnish contemporary comics got recognized by the art scene here and we had big exhibitions in contemporary museums. The first large government grants were given to comics authors which helped us to focus on our projects. Our movement of contemporary comics had also turned really international. We traveled to many events in Europe and the USA. There were several exhibitions on “the new Finnish comics” around Europe, especially in France. Most of our publications had already had English subtitles for years, so we got tightly connected to an international crowd, especially to middle-European scenes.

There had been a bunch of people already making art comics to a high quality at the turn of the decade and through the 1990s, artists such as Matti Hagelberg and Riitta Uusitalo. However, the movement I jumped into had a significant amount of people involved and the scene created its own structures, even founding a distribution company. Of course, we have two great names that made an impact in the first 100 years of Finnish comics: Tove Jansson and Tom of Finland. Both of them made comics for adults. While everyone in Finland probably read the Moomins when they were kids, Tom’s works were of course seen a bit later. This base of “comics for adults” that Jansson and Finland provided had a significant role in what the comics from my generation turned into. I must also mention Kalervo Palsa (1947–1987), a comics and fine artist that worked from the late ‘60s until the early ‘80s, who made really wild works with adult content. He and his (prose) diaries were a great influence on a lot of comic artists here.

As the medium is recognized by our art institutions, we have a quite good situation in terms of opportunities for grants and funding. You can see this in the fact that a large number of Finnish comics are getting published. Besides that, there is still the same active small press scene, the sort that I started in. However, the funding is crucial.

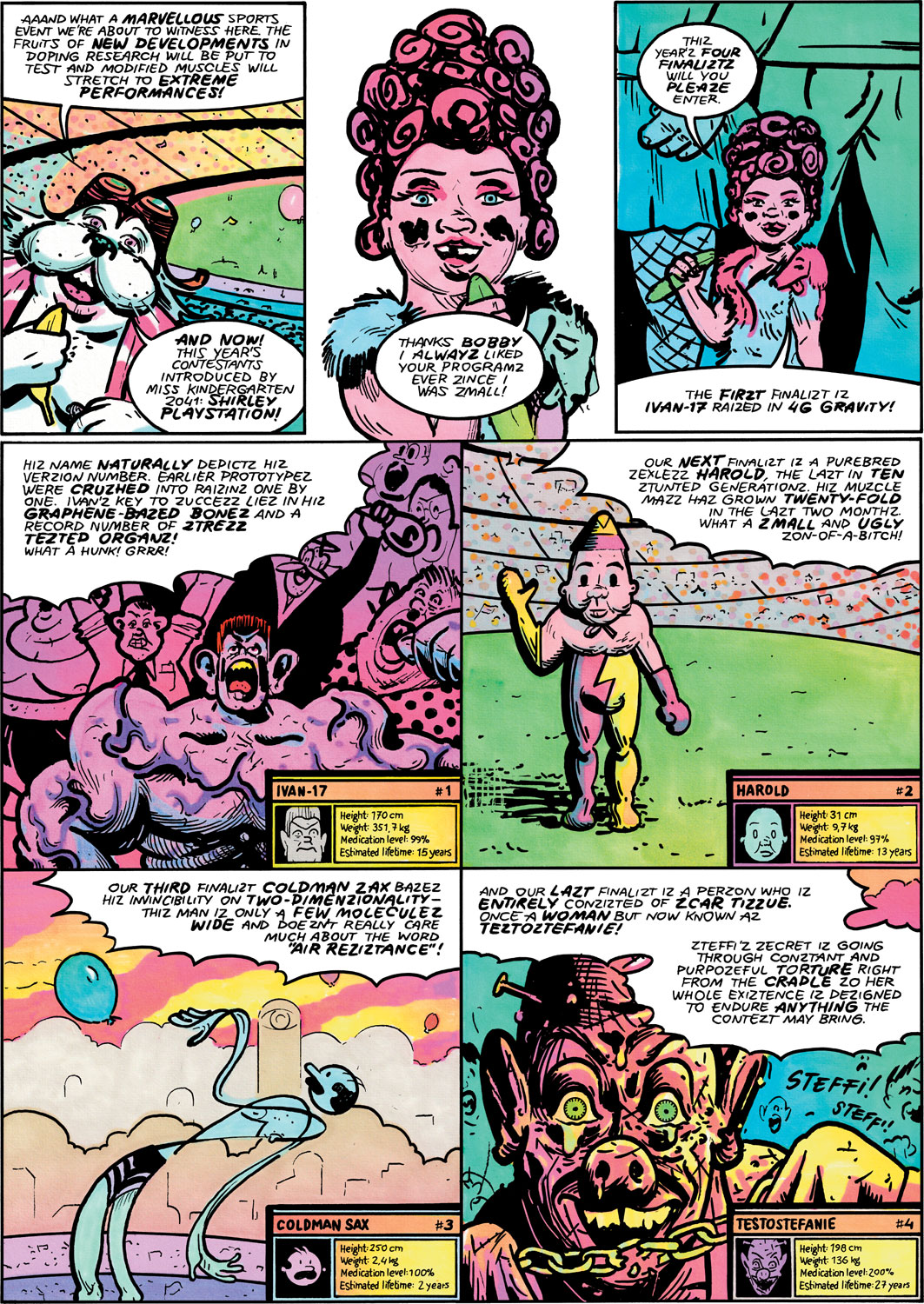

NB: I’m glad you mention 2000AD, because the strip in Future that features Bobby (an anthropomorphized otter?) and the reality TV shows he hosts really reminds me of early 1980s 2000AD, especially the sort of destructive consumerism portrayed in Judge Dredd. What was the impetus behind starting Future, what are you looking to explore in this work that you haven’t covered before?

TM: I started work on Future a long time ago, in 2012 if I can recall rightly. I wanted to do a book about “the possible futures of mankind” and that’s the path I’ve slowly scripted it to follow. Because everything is in constant change and everything happens faster and faster, I felt like I was going into some sort of black hole with the project. The subject of the “future” is so huge and unpredictable that my aim has been merely to take a look at random events here and there rather than trying to comprehensively find out “the truth” about it (which you know, does not really exist – even the laws of physics are slowly changing). I had also been planning to do a book where I would combine all the different styles and artistic identities I had been using in my work thus far. This was perfect for Future because I really needed to have a lot of different perspectives on the subject, rather than trying to explain everything linearly. I needed to have a lot of objects, subjects, styles, and ways to narrate in order to have a better view on this dark and abstract subject. It was clear from the start that Future would be a really fragmented puzzle.

In the first years I gathered material and went through a lot of utopias and dystopias in literature, movies and also comics. I find 1970s and ‘80s era 2000AD (and Star-Lord) still really visionary in many cases (the later magazines, not that much). I also noticed that, with exception, most recent science fiction was not what I was looking for, but merely genre entertainment made by genre enthusiasts for others like them. Most of the interesting material (that somehow affected what Future is turning into) is older material. However, this “background work” was, of course, also an excuse to go through all this old stuff I had maybe dipped my nose into earlier, seen but forgotten, or just heard about at some point. I was setting my mind into the mood with this stuff.

NB: On top of 20000AD and Star-Lord, what else went into your research for Future?

TM: I also watched some popular TV series like the ‘80s and ‘90s productions of Star Trek. I read a lot of traditional science fiction that I had mostly skipped after leaving my teens. I didn’t find the new material that interesting but classics by the likes of Lem, Bellamy, and Clarke are definitely timeless. Some Nostradamus quotes ended up in Future, too.

If I have to name one book that made a big impact it would be William Morris’s News from Nowhere, written over a hundred years ago. It has this dreamy tone combined with the feeling that the reader is looking in at something from the outside. This perspective was exactly what I had planned for Future as well. It’s written in a sort of innocent, naive way. Morris also includes his political views in the content. It doesn’t present our world as linearly progressing wholesomely to something modern. I think this is important. There is no need for aimless change because the world itself is in constant change. The characters in the book are highly individual as well.

I think the most interesting part in Future’s referencing is that it displays the use of styles as a rhetorical tool in comics narration. I’m mostly utilizing mainstream-ish looks that I mix with content and stories they don’t necessarily match with. I also used this kind of approach for my graphic novel The Book of Hope and, partly, with the two mute Samuel books.

NB: Have you got some grand plan about how all the different storylines are going to develop and conclude, or are you letting the characters guide you?

TM: Yes, I do have a plan. After I had done enough background work I used one year to write the script of the book. I call this a book because after all ten issues are out we’ll release it as a compiled edition. This script is relatively precise but also leaves lots of space for improvisation. My way of working has always been that I do a lot of changes and jam when working. Changes are mostly additions to what I’ve written previously, but sometimes I also edit more severely. The script I have may sometimes just include the main actions of the specific short story that I then rewrite in detail and add dialogue to before starting the actual drawing process. I’ve also left gaps in the main storylines (Future has more than ten of them) that I’m filling in now. I also have some space for new shorts, too. As the process behind Future is very slow and has already taken years, and I’ve of course got lots of new ideas that I try to include. That’s why I’ve left some space to play with. Also, as I’m dealing with the future, it’s essential I have some space that can be used to discuss current topics.

NB: There’s quite a big difference between what the popular imagination of the future was when you started this project and what general ideas of the future are becoming at the moment. Have you got a sense as to how “the new normal” may guide the upcoming five or six issues?

TM: I try to cover a lot of different perspectives of our reality and what the future might become. I knew the subject is a difficult one and I could easily fail – what I do could seem outdated in a year already. This is probably why I ground my work to material that seems to have lasted the test of time. I did note that most of this material does not try to show what our future might look like, such as what kind of laser guns we’ll have, what the fashions of tomorrow will be like, and all that; these utopias present the inner worlds of individuals. This is key with my Future project as well – I’m not trying to present our future in the way that “hard” sci-fi or commercial entertaining fiction does, but rather go through my own thoughts and fears, and those of the people I know, and from random encounters on the web or in the street.

Due to my nerdy background and growing up surrounded by home computers (I’ve still got piles of them around and still work with those as well), I have a particular interest in digital reality. This world used to be sort of its own entity during the ‘80s, but these days it’s all mixed up with actual reality, affecting all of it. In Future, I’m trying to cover some of how digitalization and social media changes our thinking and our actions during the end of the world.

NB: As you’ve mentioned, you have a background in C64 art. What tools are you using for Future, is it all digital or are you using pens and paints as well?

TM: I haven’t limited the tools I use. I like to work on paper rather than digitally, and I don’t own a tablet to draw with or something. I think that to be able to work on paper makes something “special” both for me and for the result itself. It’s often the mistakes that matter. They may create something new, even new ways of communicating with images.

When one starts to draw there is usually an image in her / his head that she / he aims at. This image is usually stereotypic and comes with a particular style and other semiotic messages. I mean: if people are asked to draw a phone, most people will draw it the same way. With digital tools, it’s very easy to reach this inner target (which is mostly subliminal), as you can create every single detail and line unlimited times. This will result in an image that did not really come from inside of you but presents the general experience of the object and its “message.” What I like when working on paper is that I make mistakes all the time, mistakes I cannot undo. These bugs are something that may change the direction of the image or create some changes in the style as well, even the narration. So I would propose one’s work is more individual when you work with pen and paper, or with other equipment that may be difficult to use.

However, in Future I do most of the coloring on a computer, using Photoshop and a touchpad. Not all of it, though. The “Centra” story is totally handmade and here and there I’m mixing hand-applied and digital coloring. I draw most of the pages on relatively big paper, A2 and even A1, while some pages have been drawn smaller than the size they’re published as.

I also like the fact that working on paper is slow. Especially with Future, because most of the pages contain a lot of information. This slowness gives me time to think about what I am working on and usually leads to small changes and additions here and there. These changes make the work better.

Anyway, I’m not a police officer telling people how they should draw. You can reach the same results drawing both digitally and with analog equipment if you’re just aware of what you’re doing. The only advice I can give is that an artist should not be limited by the tools or equipment but rather should be able to work with anything that’s to hand, and even with any form of expression. That’s also what I say to students on the rare occasion I teach or lecture.

NB: Regarding what you say about enjoying all the different aspects of drawing on paper, it seems that the idea of the line, your pens on the page, is where you think the work comes alive. Is that fair to say?

TM: I have always been mesmerized by the moment when something new is born in front of me on paper. In the past, this would have been partly technical – tryouts that failed or succeeded. However, the particular moment “when something starts to happen” is still magical. These days, the actual making is relatively different. I think the creative work takes place at all steps of the process. My ways of working are pretty organized and planned and I do a lot of groundwork, the last phase of which is the actual drawing.

As I said, I always leave space to improvise, and this is true to every phase of my work. This is not only good for the content but also keeps me as an author alert and motivated. To draw something is usually the easiest and most fun part, this is maybe because I have worked in images since I was a small kid. Of course, sometimes I build really complicated images with styles and methods that are really slow to work with. It’s important to stay focused, however. I am very aware that if you work every day with images it’s easy to fall into mannerisms and even get bored. That’s something to avoid. One way for me to avoid that is to do things differently from what I am used to, and challenge myself a bit all the time.

NB: The series has this “back to the future” vibe to it, in so far as you’re using vintage and retro aesthetics while still pointing towards things that may be ahead of us. I notice that (underground) comics which use internet aesthetics don’t really adopt the Tesla aesthetic or iPhone’s glossy interface look for satirical means. Do you think there’s a reason for that?

TM: Well, I suppose that Tesla and iPhone are machines developed by engineers, and most of them are – probably – men. These devices may change something in our lives, raise interesting questions that turn into sci-fi dystopias (such as Tesla car crashes), but I’m merely interested in how some ordinary Joe sees the future. Suppose I could be interested in what happened with Apple’s development in the late ‘90s. I’m not interested in the machines as objects (well, maybe the “machine of capitalism”) but mostly what’s inside of them and who is using them.

For Future I’m using a variety of styles and these styles carry messages. At some point I’m using a style that might support the storyline, at some point this style may contradict or juxtaposed with the story and then there are all the possibilities in between… and I’m playing with all this when everything is up in the air.

I’m also aware that some styles may interest specific audiences while some others gain attention from totally different groups of people – the 2000ADish pieces may be a vibe for people who read similar stuff in the past, while the aforementioned “Centra” storyline may attract people interested in current trends and outsider art. These two audiences are mostly different from each other and don’t usually read the same magazine. I’m using the styles as bait and setting traps for different readers. It’s interesting to observe what parts different readers are interested in.

Anyway, I’m really mashing it all up as well and using styles that I do not even like myself that much. Even those paths still carry a message and maybe remind a reader of some nostalgic experience from the depths of their soul.

What’s notable is that when using all these different but familiar styles, I’m still telling about our reality and our possible futures. So, while the reader laughs out loud (which I expect) they may also feel this uncomfortable feeling inside.

NB: I read that you were involved in the design of Habbo Hotel [a virtual chat room launched in 2000]. Is this true? I was reading some Chris Ware recently and some of his pages were reminding me of Habbo Hotel, the way in which a story is developed within the bird’s eye view of a setting, and also what looks to be precise and repeatable digital art.

TM: I hopped into Sulake Labs, the company that developed Habbo, when the hotel was being beta tested. The year was 2000 and I had just moved to Helsinki to continue my studies at university. I saw the Finnish version online and was immediately interested in its functionalist visuals and its (then) new ways of communication. I had a long history with pixel graphics as I had been drawing with C64 and Amiga since the mid-80s. So I contacted them and joined up. There were six of us in the beginning and I stayed for five years working as a designer and later as an art director.

Habbo was just one thing we did, and lots of material never really got released. I did this while studying and doing comics, which I drew at night after school or work, so those times were kind of hectic. Anyway, I left in 2005 when the company had a few hundred people in it and just too many of them were men in suits telling me to do this and that. The early years of Habbo were truly interesting and taught me a lot. The service was really different from what it is now. When we started it, the audience was not defined, we just wanted to make some new kind of tool for communicating online. Most users back then were young adults in their 20s and 30s. After the product was corrupted by the salesmen it became targeted to kids. I don’t know what the general situation is now, but I’ve felt a certain pride noticing that during the Covid-19 crisis people have been using Habbo to see their friends and organize events. That was one of the main things it was made for.

This isometric “military view” that Habbo utilizes is very common in the history of gaming and virtual worlds. Its aim is to present the most of what could be seen, so it’s a mostly functional way of showing things. I’ve also used this view for some illustrations and also for some parts of my Samuel comics series. However, only drawing from such a perspective makes the process very slow. Even though I use a sort of “still camera” a lot in my comics, I still like the idea that the camera can wander freely and that I may use any perspective at any time. I must just be wise with how I use this freedom, and even though I have the freedom I try to minimize the variety of camera angles I use.

NB: There’s some discussion braided through Future on the role of art to “help” or “save” society – this may be my bias revealing itself, though. So far I get the sense that the series is pessimistic on that front. Is that something you’ve put in there on purpose, what are your thoughts on it?

TM: Well, there are different storylines in Future, and they are not always talking about the same future, but presenting different perspectives on the subject. The story you mention is titled “Culture” and it presents a dystopia where all art has been declared illegal by the populist right-wing. In the middle of this, a gang of shabby bohemians gather underground and start to work on something together (I won’t spoil what happens from there).

I would say that Future is (or has been until now) pretty dark in its humor. Maybe some people read it as pessimistic. Some storylines may be more dystopian while some present utopias. I promise there will be twists and turns in all the stories but I don’t want to spoil anything here. Future (like most of my work) has philosophical aspects to its themes – how can we work this current mess into something sustainable. So, in a way, Future tries to find answers and also to educate, in a sense.

NB: Could you give a little summary of what Kuti is up to at the moment, and your involvement with it?

TM: Kuti (the newspaper) and Kutikuti (the collective) are continuing, and pretty stable. Our collective turned into an open contemporary comics association some years ago and now has 50–60 artist members. We had to either change it or quit it and we decided to do the former, so we hired a half-time producer and invited in lots of new people, including fresh young(er) artists. We had been doing everything ourselves for fifteen years and it was essential to have some new blood to keep things rolling and evolving.

It’s kind of a miracle that we’ve managed to release Kuti already for over thirteen years and kept the steady pace of releasing four issues a year. Indeed, we haven’t really missed any deadlines apart from a few days here and there. The magazine is funded partly by the Finnish government and partly by ad sales, and, of course, also partly by subscribers (which I highly recommend everyone to become). Nowadays we have different editors for each issue. Some issues come out with themes and invited artists, but we try to have at least two open call based issues per year. I would say Kuti has found some sort of balance with everything. It was very fresh when we started it in 2006 and it still manages to stay focused and to present new artists and new ways of doing comics, even though there has been a big boom of art comics popping out everywhere for a long time already. Having changing editors also makes the issues quite different from each other.

Our current issue is co-edited by Finnish label Rab-Rab and its theme is war. The one in September will be an open call issue with the working title “Digi-Kuti” – for that we’ll search for comics with added content, interactive elements and works that are in dialogue with digital comics, social media and the web. I’m editing that one. It will be a pretty free-form issue.

There are financial problems with what we do every now and then but nothing that we can’t get over. Everything Kutikuti does is non-profit, but due we’ve got a big bunch of people working on it, it has remained pretty fun to do.

My role these days is in the background, mainly with Kuti as I’m not on the board of the collective at the moment. I’ve done the ad space selling for years now and I assist the board. Since I moved away from Helsinki, I haven’t been that much involved with everything like I used to be. In the past, we basically lived at our studio. Back then the small collective was a bunch of friends hanging out together and making comics. Now people have families and day jobs. Things change, and they’re supposed to.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply