There’s always a flurry of excitement when comics from outside of the Anglosphere get translated into English. We know that comics have many local iterations, but even though the visual arts are sometimes referred to as universal languages, actual language, cultural and economic barriers stop everything from circulating everywhere. Thanks to Paradise Systems, then, for sorting out a way for us English-speaking Westerners to get to know a bit more about the exciting Chinese comics scene.

A translator and student of Chinese, R. Orion Martin founded Paradise Systems after making contact with Chinese comics artists while living in the country. Since then, Paradise Systems has partnered with Latvian outfit mini kuš! to publish a series of one-shots, released Naked Body, the first major anthology of Chinese comics to be published in English, and, most recently, published an ebook of Chinese comics made during the first lockdown in 2020.

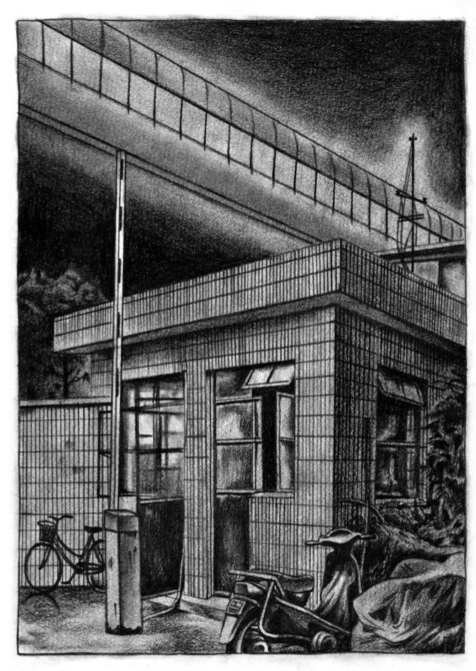

It’s not possible to generalize about the art in these comics, though they could be situated in what can be recognized as the comix tradition, and they often edge towards a more artbook or fine art-inspired aesthetic. I video called Orion over the Christmas period to find out about his background, how Paradise Systems came to be, the Chinese comics scene more generally, the political implications of this work, and what the future holds.

Can you say a little bit about your own background in comics and publishing?

I really came at it from a writing and translation background. I was living in China and studying Chinese. I started to work there as a translator, mostly as a translator of art-related documents but then also writing articles about different art institutions and shows that were going on there. Separately from that, I’ve always loved comics, and I started to discover the work of this community of artists making comics in China. And the more I found, the more impressed I was with all this amazing output, and the range of work going on. I’ve never done an MFA or anything like that, it just developed gradually.

What took you to China?

I did study Chinese a little bit in college as an undergrad, and I was able to go on a trip with school to China, and after I graduated I was like, “I’d really like to learn more about this place”. I just felt like there was so much more to learn and think about there. I spent about three years living in China, and since then I try and go back three weeks to a month every year to keep up with contacts and learn more.

Is there somewhere specific in China that you always return to?

First I was living in what’s considered the west of China, Kunming, and then I moved to another city that’s considered to be in the west, despite the fact it’s smack down in the center, called Chengdu. When I go back now, it’s often to the larger coastal centers, and I don’t often make it to those other cities, just because there are so many more artists based in places like Beijing and Shanghai.

Last year I had a chance to go to Taipei for the first time, and that was pretty exciting, to some of the people and see all the amazing work coming out of that community.

What’s the comics ecosystem like in China? I read that it’s mostly webcomics?

It’s complicated, and there’s a lot I don’t know. Especially, there’s some truly massive mainstream comics, and they link in to the huge print publishing industry. That whole ecosystem is something that the artists I work with do not engage with very often, and what I’m more focused on is people independently publishing, people printing their own books, and there’s a few bookstores that sell that kind of material. But in recent years comics have been distributed either online or at book fairs, and in the last couple of years especially these book fairs have just proliferated all over China, and they’ve been really exciting to take part in.

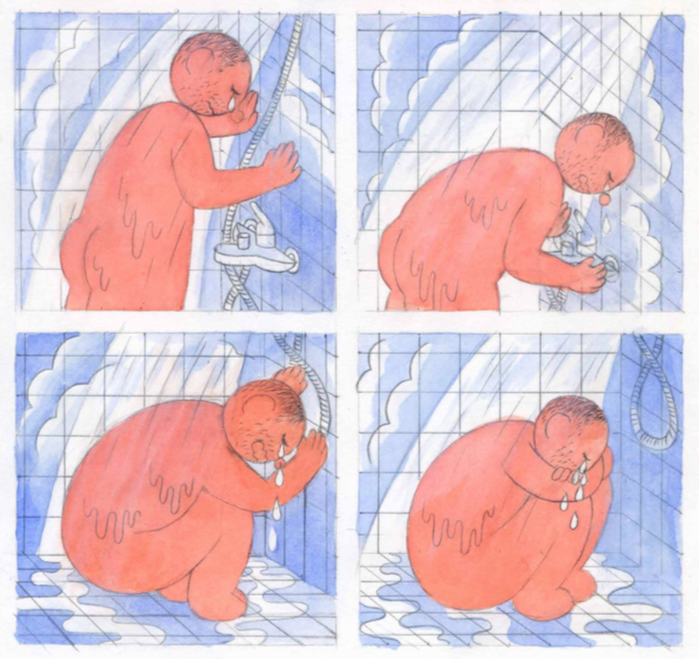

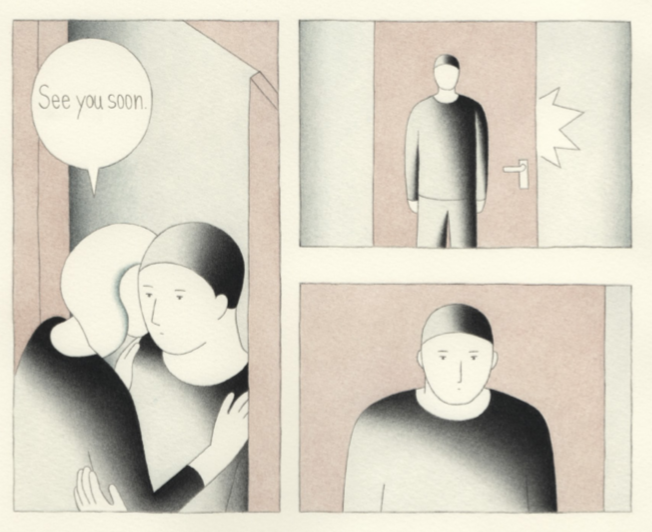

A lot of the work you’re publishing tends to have a focus on the personal, not identity political work necessarily but certainly work about isolation and anxiety, etc. Is this representative mostly of your tastes or of the scene more broadly?

The artists that we work with are usually solidly in the indie publishing realm. And that can mean a lot of different things, but it generally doesn’t include people doing broad, mainstream work. I think that one of the goals for Paradise Systems is to encapsulate the diversity of what is going on in the independent comics scene.

I see you have a board. Are those people you’re asking for advice from? How collaborative is Paradise Systems?

It’s super collaborative! When it started it was just me, and then two people I’ve been working with a lot, Jason Li and Xinmei Liu, we’re the core team right now. For example, Xinmei edited the recent ebook we put out. I don’t really do anything without talking to them, and they also have their own projects going on.

Are people pitching projects to you now?

People have been reaching out to pitch projects to us, yeah. However, we have such a long list of projects that we would love to do but haven’t had time to do, we don’t tend to end up accepting pitches. It’s not about the quality of that work or anything, but about how many projects we would love to do, and how limited our time is.

Are you distributing your books yourself?

Naked Body was distributed through Consortium, and we had some support from Beehive Books, which is a Philadelphia-based publisher, and that’s the first one we’ve done like that. But a lot of our books don’t make sense on that scale. If we only have four hundred copies of a riso printed book, it doesn’t make sense to do that.

What’s the thing that makes you go from liking a book to wanting to translate and publish it?

Oftentimes, we’re really excited by someone’s work, and then we’re trying to think what would make sense to print in English. One of the things on my to-do list is to read this sprawling – I think it’s over six hundred pages – webcomic. And it’s a really beautiful work, but I think that may be outside of our ability to publish right now. So, I think that the books that we end up publishing usually start with us liking someone’s work, and then it ultimately comes down to what makes sense to print. Some of the work we see are these vertical comics that don’t make sense to print. Or they’re way too short.

I wanted to ask specifically about your relationship with Yan Cong, whose Narrative Addictions is the anthology that you reprinted in 2019 under the title Naked Body. And how are you coming across new artists, are you doing your own research or have you got scouts in China you’re working with?

You can’t really read about Chinese comics for very long without running into Yan Cong’s work. He’s such a central figure and makes such amazing things. He’s one of the first people I encountered and I interviewed him for Hyperallergic years ago before I was even independently publishing stuff. The Chinese edition of Naked Body that he published was one of the earlier books that I found, and I thought it was such exciting work.

In terms of how that got started, like everything there’s people in the community who are like connectors, and Yan Cong is definitely that sort of person. Since then, it’s been a bit piecemeal. I’ve just been trying to keep up with what people are posting on social media, and which artists are interacting with each other.

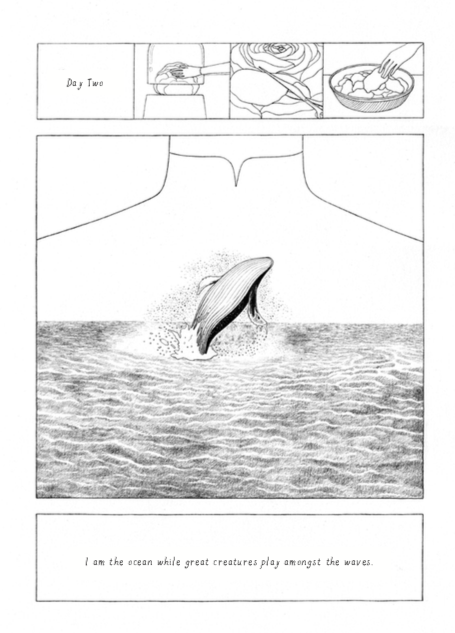

One thing to note is that artists don’t tend to one day think of making a well-scripted, thirty-page comic. There’s usually a progression towards that. What’s been interesting for me to keep note of is the way that people are becoming a lot more oriented around making comics now because people are printing stuff for these book fairs. For a long time, we were looking at stuff made to be a webcomic and we were thinking about how to translate those into print, and now people are thinking about print all the time.

Nice, so it seems that people are becoming a little more interested in the materiality of the book. That leads me nicely into a topic I wanted to ask you about: the lianhuanhua and manhua genres, which – as far as I’m aware – are very format-oriented. (You wrote an article about lianhuanhua for The Comics Journal). Could you talk a bit about their importance?

Well, lianhuanhua is such a special thing. Let me first touch on format-oriented work, because there is a lot of that going on now, and I think that is a very exciting thing that has been made possible because of these book fairs. I’ve seen a cartoonist make a book where every panel is a sticker and you can put them in any order your want, or, doing really elaborate riso experiments.

When we’re talking about lianhuanhua, it’s important to note that it’s comics adjacent, or, at least, it hasn’t been recognized as a piece of comics history I don’t think. I’m always making the case that it should be considered a historical comics medium, but in China, they were a pulp comics thing used to disseminate pop culture. A lot of it was adapted from other sources, and they were really really popular. The scale of this industry is way bigger than anything we have in the United States, for example. I think that there is this connection between that and the comics industry in China now, but it’s not like people making comics now are thinking “Oh I’m part of the lianhuanhua lineage”, they think of themselves as being part of this international, underground comics movement.

In some of our publishing work, we’ve pushed some stuff into that format in order to draw that comparison, so there’s a number of works that were designed for being distributed on the web that we’ve published as lianhuanhua format books. It’s been interesting to respond to that in different ways.

You just spoke about how, and I’ve read this in other interviews with you, this scene is very much inspired by the American underground. One of the ways that China is portrayed in the news media is as this hermetically sealed, homogenous blob that combines modernism with Chinese traditionalism. Do you have a sense of what specific artists have made an impact in China, what were the routes for those artists getting into China in the first place?

My background is in contemporary art, and that’s where you see a lot of this cross-pollination happening even earlier than with the comics. Even back in the 1980s, people were importing philosophical texts and contemporary art, and artists in China were interested in thinking “what does it mean?” to make work like that in China. They understood that some contemporary art styles were culturally imported practices and that they’re also responding to a lineage of ancient Chinese art that has its own traditions.

In comics, it’s a bit of a different situation. There’s always a very international tradition with reading comics in China, which is reading imports from Japan. That started in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Most people grew up reading these imported versions of Detective Conan and others. And then some time in the 2000s, people really got into sharing comics from abroad on BBS forums and early social networks, and that is when some people started to really connect with the underground traditions from the United States and Europe.

To go back to Yan Cong as an example, he always says that he was trying really hard to draw in a Manga style, and then when he first saw comics from Europe and the United States, it just clicked. You get to now, and everything’s taken to a million percent. So for example, there’s an amazing edition of Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina being published by a major Chinese publisher. A lot of young people are studying abroad, that’s another way influence goes back and forth. So, at this point, and you can see this in the work, the comics don’t look like they come from some completely different tradition, it’s very recognizably part of an international discourse about comics.

Definitely, and the fact that there isn’t one style, you can’t really typify the scene, is very interesting, and the diversity of subjects as well. With your background in translation, I’m presuming you do a lot of the translations yourself. On the act of translation, what are the main road bumps for translating Chinese into English?

Translating is such a fascinating thing to do. I think the biggest stumbling blocks we run into is when there’s a work that is so culturally specific that it doesn’t really make sense out of context. We’re working on a book right now which is baked into this cultural tradition of having marriage markets where parents will go to public parks and they will take a little write-up about their children, and they’ll try and arrange marriages. So, the artist of this book, Sadan, has made a sort of surrealist take on that, and we’re wondering about how much context can you give without overexplaining the subtle cultural critique which is going on in the original version. And the most challenging thing is humor. It’s difficult to capture what makes something funny in the original version. You always end up trying to make new jokes that supplement the work when the translation is lacking.

Articles about Paradise Systems tend to mention censorship issues regarding some of the art. How restrictive is that censorship? Are you publishing work that might not be able to be read in China? And how does that affect the work being produced?

Print publishing is highly controlled, and we’re not looking to break any rules. There’s a lot of ways to work around something that might be a formal restriction, especially because what we’re doing is so small-scale and indie-driven. But there are challenges in any kind of independent publishing, and the rules change all the time. If artists are selling work online in China and it’s found to feature illicit content, such as nudity, their store might get totally closed down and there’s no way to appeal that decision, and that can be really frustrating for people.

Is there much of an intersection between politics and cartooning in China?

There’s definitely not a lot of explicitly political work. You won’t see much work where the Chinese Communist Party is brought up in any way. I think there are a lot of reasons for that, including that I think many artists just aren’t interested in commenting on politics. And I should mention that there is a community separate from the one I’m involved with, who are making very political work. Some of them are connected to the Hong Kong protest movement and things like that.

One of the exciting things about making Naked Body is that there were some more works that touched on more political themes. There was one piece in specific, which was a kind of new take on the Emperor’s New Clothes, and in it, the artist brings in topics such as the Party and consumerism.

On the other side of the coin, these artists are finding support for their work. How are these artists funding their work – do they have side jobs as graphic designers or are they making money as artists?

It really depends on the artist. A big group of people do freelance editorial work. Another group, including Yan Cong, work in a contemporary art context, and alongside his comics he’s also selling paintings. I think that’s another thing that’s driving how diverse the scene is right now. People are bringing their influences and backgrounds to play. The downside of that system is that there are not many people making long-form work.

With it having such connections to the contemporary art market, are people seeing comics as part of contemporary art?

Well, speaking about the US market, I think there is this interesting thing that happens where there are some publishers that are in between the art book fair and the comics fair, and I definitely see a similar thing happening in China where under the broad umbrella of “art books” people are experimenting with comics in different ways.

Touching lightly on a subject I know only very loosely: Paradise Systems is being pitched as a publisher of Chinese work, but you’re also printing work from Taiwan, and you’ve visited Hong Kong too – there’s controversy and contentions regarding political and cultural identities between the mainland and those islands. Is there friction between those artistic communities?

I haven’t noticed any frictions, but the communities are quite separate. Like in Hong Kong, all the artists there know each other, but they don’t necessarily know folks on the mainland. This isn’t always the case, and some people act as a bridge between different worlds, but they are pretty separate communities. We’re working on a book with a Taiwanese artist now, and it was different than when we worked with artists on the mainland, who knew the other artists we have published, whereas this time it was like starting again, and we really had to establish trust.

What’s your plans with Paradise Systems moving forward? You just published this ebook of comics made since the start of the pandemic…

Yeah, there is a group in China called Art Book China who were putting out a series of comics about life under lockdown, and a lot of the stories that ended up in the book come from that. As soon as we started reading that series, we were thinking that it was really groundbreaking work and that it would be fascinating to have some of it in English.

I personally love print books, so we hadn’t worked with ebooks before, but for this one, some of the pages were in different formats, and we wouldn’t have been able to do it as a single print book, so this was an exciting experiment. A lot of our plans for the future revolve around print, and things more like Naked Body, which was a really successful project for us, and really got us thinking about how to do a large-scale project like that.

I’m guessing this is all a labor of love for you?

Yeah, I have a separate job: working as a tax advisor. Jason and Xinmei both have other commitments as well, so this is definitely something that we do because we love doing it.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply