COVID-19 has done a lot to break down the world and keep people apart, but it has also helped people forge new connections. As COVID-19 struck mainland China, our publisher Alex Hoffman began corresponding with Kristina Stipetic, an American cartoonist currently based in China. The Chinese comics scene is mostly a mystery to comics enthusiasts, although we know based on the work of NY-based publisher Paradise Systems that there are many talented artists working on comics there. Kristina offered us some insight into China’s burgeoning comics scene, and today she brings us an interview with Zhao Chunlin, a cartoonist, and illustrator from Chengdu. Text in bold is Kristina’s, and she occasionally gives asides throughout the interview in bold text in order to give context to something Zhao Chunlin has said. The text has been lightly edited for clarity. Please enjoy.

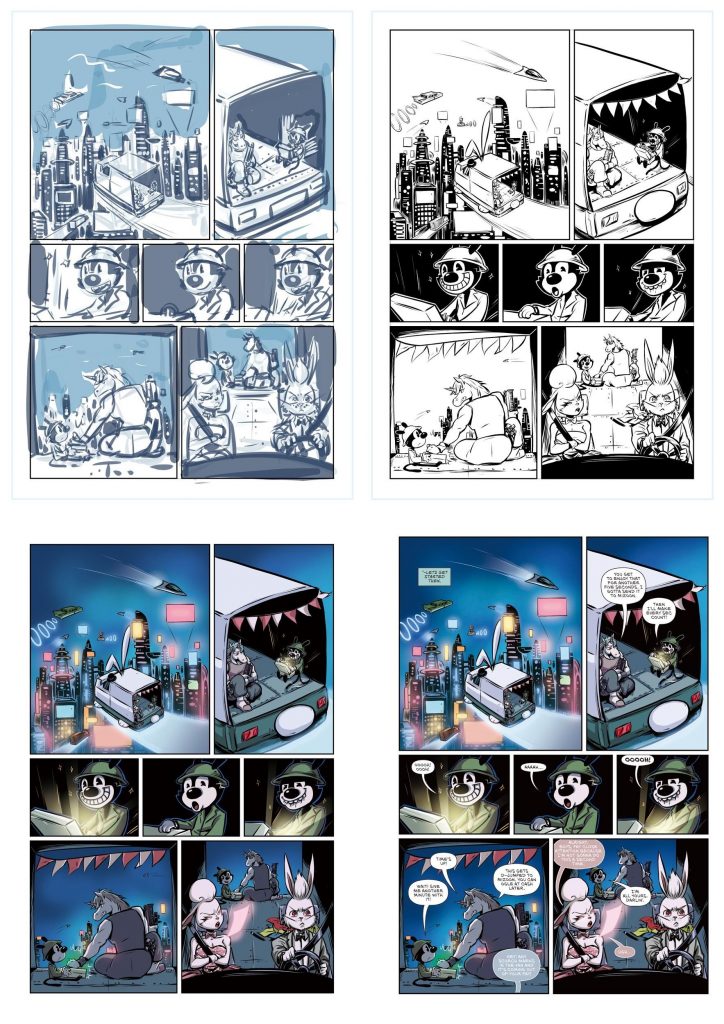

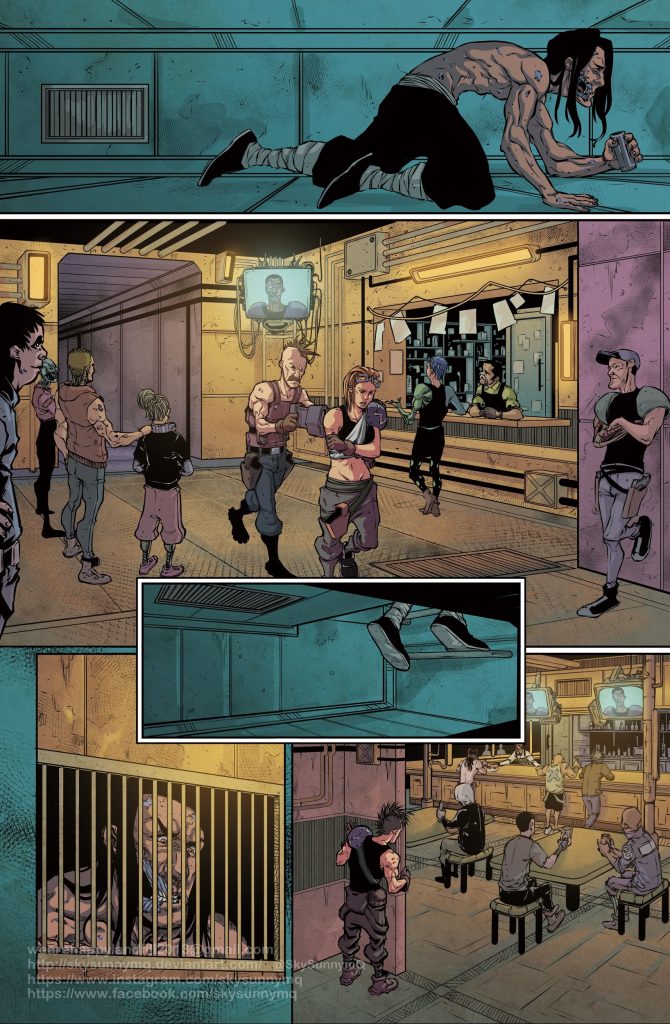

Kristina Stipetic: Zhao Chunlin is an illustrator and comic artist from Chengdu, China. She is the main artist on the comic series Tom ‘n Artie, and the colorist on Wretches, a comic miniseries which has recently been opted for a one-hour TV special. I first met Today we get a rare glimpse into the Chinese comics world as Kristina Stipetic sits down to interview Chinese cartoonist Zhao Chunlin at Shanghai Comic Con (SHCC) in 2016 when we were both exhibiting in the Artist’s Alley. For this interview, we talked about how her career as a colorist got started, her experiences working for Chinese and American clients, and comic conventions in China and abroad.

Kristina Stipetic: Tell us about your background as an artist. How did you study art? And in particular, how did you study coloring?

Zhao Chunlin: I was fascinated by Japanese manga growing up. I remember drawing them for fun even back in kindergarten. I used to think that being a cartoonist could be my lifelong dream and, even though it seemed too hard to achieve, still I held onto the idea. Entering middle school, with the heavy schoolwork and the thought that some dreams were unattainable, I hardly drew anything for three years. In high school, I began to sketch a little bit again, and the teacher happened to see it. At that time, I was really into music. I even set my heart on learning to play instruments like electric guitar. However, the classroom teacher suggested I continue to draw. With careful consideration, I quit music. It wasn’t until my last year in high school that I really started studying art (as for the reason I suddenly chose to study art in high school, it’s a long story and has to do with the education system in China, so I’ll just leave it at that).

Two of my high school classmates had been studying art for a long time, and they often sent their work to the art teacher for advice. Following suit, when I decided to pursue the path of art, I also took my drawings to the art teacher. He asked me if I had studied drawing at all, and my answer was no. One of the classmates snickered. Knowing that I only just began to learn the basics at that time, the art teacher said he wasn’t willing to teach me, even for extra payment, which meant it was too late to get good grades in the college entrance examination. I don’t remember my feelings then, but I didn’t let myself get crushed by his comments because someone with such a harsh attitude couldn’t be a big deal himself. I continued to learn drawing with steady progress. In the end, my grades were better than the other two students.

I got into an art college very smoothly. However, there wasn’t a major related to cartooning or illustration at school, so, reluctantly, I became an animation major (by the way, I still love music. My university is famous for its School of Music, and I got to see a lot of free performances back then). I learned a bunch of software including Flash and 3D MAX. Now my work seems to be totally irrelevant to my college education and I forgot how to use the software. I remember there was a time I made a decision to complete one drawing per day regardless of content or level of detail, and I accumulated a lot of experience that way.

The first time I truly began to do coloring was nearing graduation and I had to find an internship. All I wanted to do at that time was to get a job where I could draw, whether it was comics or illustration, it didn’t matter. I sent out my resume to several companies, including one art studio in Chengdu. During the interview, I found out that the studio usually worked for foreign clients and my job there was coloring. That was when my career started. At that time, I wasn’t into manga that much anymore, instead I developed an appreciation for American-style comics. I really liked my job there and learned fast. There was some office drama and I thought about changing my job. I went to a few interviews, but none of the jobs seemed cool or interesting enough. Plus, no colleague is perfect. So, I stayed and did some side projects at the same time. A year later or so, I left the studio.

Kristina Stipetic: What attracted you towards Western-style comics as opposed to Japanese-style comics which are so popular in China?

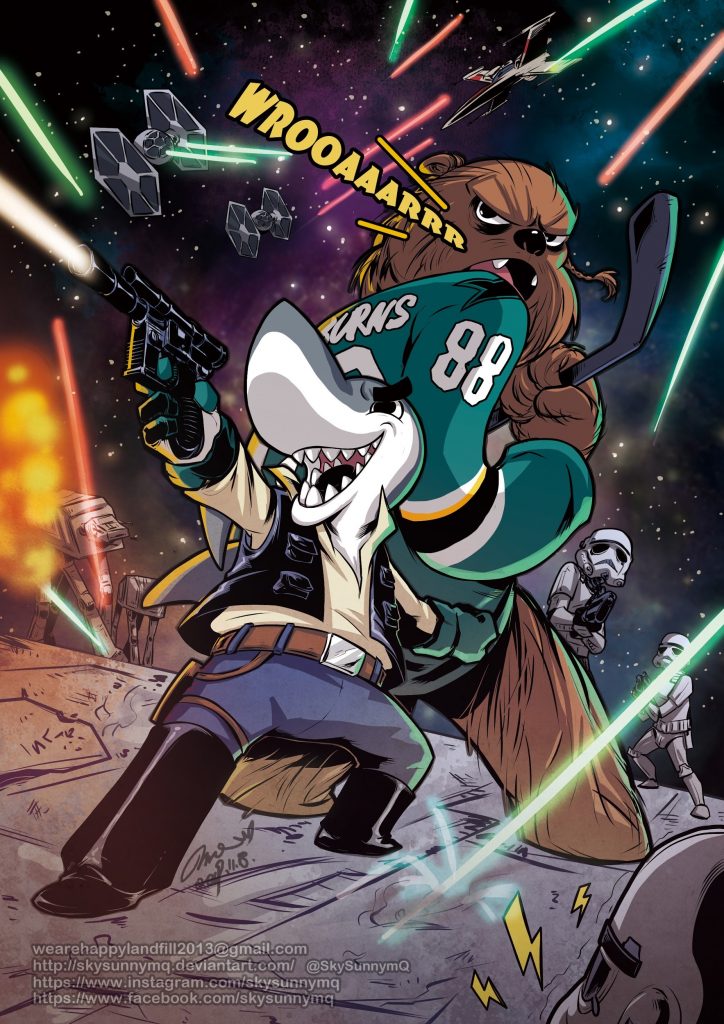

Zhao Chunlin: As I said, I was really into Japanese manga growing up and didn’t start to have an interest in American comics or animation until entering college. The first two Western animation series I saw were South Park and Futurama. They opened the door for me to see many more good works since then. I also happened to get to know Gorillaz and immediately fell in love with the style of their characters, so I tried to draw in a similar way (even my email address is named after their song called We are Happy Landfill!)

To me, a good story is much more important than skills, and that’s how I felt when I first got to know American animations. Some art styles may seem simple but the story is really interesting. Skills can be perfected through practice. However, to make the content appealing is not that easy. It means you have to be good at telling stories, not just drawing a character with a cool posture and hope it can get all the work done. Every detail should be able to express something.

After graduation, while working for the art studio, I got to know all kinds of American-style cartoons (most of them were animation actually, I seldom read comics). In my opinion, the comic market in the US is very diverse with different styles. No one would say “this one is not good” or “that one has no market potential”. No one asks you to draw like Marvel or DC does. Maybe that’s the reason I got the chance to try styles or patterns that were not mainstream.

Kristina Stipetic: There is a fair amount of freelance comic work in China, especially recently through web platforms like Tencent comics. What is your experience working for Chinese companies?

Zhao Chunlin: Like I mentioned above, the inclusiveness varies among Chinese and Western markets. Though there are many paying opportunities for cartoon artists in China, the payment can be very low while the workload is pretty heavy. It will slowly drain one’s enthusiasm, and, as a result, an artist may lose his/her unique art style. On the contrary, foreign clients usually give you enough time to finish. They won’t ask for three to five pages done a day, or say, “You’re good at drawing, but I’d like you to change the style into this or that”. They always email directly saying, “I like your style and hope you can draw my story.” I seldom work on Chinese comics now, although I still get contacted from time to time. Usually I’ll share those resources with my friends.

I do work on other, non-comic art projects in China like illustrations, provided the payment is reasonable. The longest cooperation I have is with game streamer Hawkao. I’ve been working for him since 2015. I also worked with China Post [the national postal service of China] for three years drawing commemorative postcards for them. Last year, I designed a mascot for a major exhibition.

I haven’t read comic books for a long time and don’t know any Chinese paper media that still focus on comics. It’s really impressive to continue to do paper comics nowadays.

Kristina Stipetic: That’s true. I used to collect Xia Da(夏达)’s comics in print, but her most recent work is a webcomic.

Let’s talk about the challenges of having a career when your clients are almost exclusively in another country. There’s always a lot of stress working with new clients, and when you don’t live in the same country, it does make you a bit more vulnerable. I’ve certainly felt that way. How do you navigate that? Any strategies you have for choosing good clients or protecting yourself?

Zhao Chunlin: Whether it is in China or other countries, people face similar situations when looking for a job online. I consider myself lucky that I haven’t met any fraud. One of my friends encountered an unfortunate case once: she signed a one-year contract with a studio and worked for half a year without earning any money.

After hearing what happened to my friend and reading about similar cases online, I am more cautious now. If someone comes to me for work, I usually ask what studio or company they belong to, do they have a website or any previous works, etc. I also Google them to check their reputation. It’s important to ask for the name of the company, especially in China. Other than that, I also have many requirements. The clients need to send me drawing samples and tell me the deadline and budget in advance. If they can’t give a clear answer, I’ll hesitate to consider taking the job. Some clients are willing to cooperate and prepare what I asked, but others don’t reply at all because I have too many demands. Be careful with these kinds of clients, they may not know what they truly want. If a client tells you that you can draw however you like, it usually ends up with him/her never being satisfied. If a client can’t make a clear request and doesn’t want to think through and make up his/her mind, I’ll decline the offer.

I’d also like to speak about time difference. Not long ago, I was talking to a friend about this topic and found out that we both love the time difference! Usually I check my emails once in the morning after getting up every day. Emails are usually very formal and organized. I can draw according to the requirements from my clients and reply to their emails after the work is done. Then I won’t check the inbox again that day. It forms a regular routine for me. On the other hand, most of the Chinese clients like to communicate with instant messages which keep interrupting my work process. It takes a toll on me to draw and reply to constant messages at the same time. And generally speaking, their messages are very casual. They may send anything without a second thought and regret their previous request all of a sudden. It really makes you tired and inefficient. I used to be a bit obsessive, sometimes I would get up after receiving feedback at 10:00 p.m. and modify the drawing until late at night. The next day I woke up late and the clients were unhappy that I hadn’t replied to their message sooner, which really hurt me.

The time difference has given me the “justification” to ignore some messages and my clients are very understanding. Since most of the foreign clients contact me because they like my art style in the first place, they don’t ask for too many modifications. In my opinion, emails are more formal and clear, and clients can write their demands in detail.

Kristina Stipetic: How did you meet James Roche (creator of Wretches)?

Zhao Chunlin: I don’t remember exactly how we got to know each other. We have been working together since 2015. He is one of the three longest-serving clients I’ve had. Although there are only 6 issues of Wretches, it took us 5 years to finish. The first issue had even made it to a Chinese sci-fi magazine in 2017.

I had the first issue of Wretches at my booth when I attended BJCC [Beijing Comic Con, no longer active]. A visitor from abroad saw the comic book and said he had also seen it at NYCC. Later that year, he went to NYCC again and James was there, and they sent me a picture of them together at the comic con.

I’ll continue to travel abroad for comic cons when it’s safe. I may get a chance to meet James in person someday. In 2018 and 2019, I mainly went to comic cons with another major client of mine, the writer for Tom N Artie. I’m sure I’ll be able to meet with more clients I’ve worked with in the future.

Kristina Stipetic: Last year, you came to ComicUp (CP) in Shanghai for the first time, welcome! What was your impression of the country’s biggest comic convention? Did you find it very different from Chicago Comic and Entertainment Expo (C2E2)? You also mentioned that Chengdu has a comic con, tell us about that.

Zhao Chunlin: I know this is supposed to be an important topic, but I really don’t know where to begin. In my opinion, C2E2 and CP are two completely different kinds of comic cons with different audiences, scales, business models, and resources. It’s really hard to compare them. I can’t say which is better, but to me, CP doesn’t appeal to artists like me, so I may have many negative experiences of it.

The first time I went to C2E2 was with another artist, and we had one booth that was big enough to exhibit all of our works. Compared to that, the size of the artist booths at CP and other Chinese conventions is too small. To be honest, I was shocked. I wouldn’t be able to show all my art even with two booths, let alone get some drawings done there. From that point of view, I think even though CP is the largest comic convention in China, they fail to give artists the best experience. The booths were too crowded which was not ideal for me. There is also another difference between comic cons in China and abroad. Conventions abroad require artists to be present while there is no such rule in China, so there is a lot of consignment.

I also notice that visitors at Chinese comic cons are purely strolling around from one booth to another. You can hardly see featured activities, and even if there are any, they lack preparation and publicity. Events like C2E2 or SHCC feature a rich variety of panels and activities. Some visitors may stay longer to participate in panels. In fact, insignificant artists like me can easily be neglected in such a big convention. Many visitors come to see celebrities or the booths of famous companies, and they may only visit artists’ booths when passing by. If the organizer cannot find ways to make visitors stay, it will be a bad experience for us.

It feels like cosplay draws much more attention than other things at a comic con in China. Most visitors are of a younger age. Back when electronic payment was not common, there were fraudsters pretending to be ordinary visitors and using counterfeit money at cons. The solution the organizer came up was to ban visitors above 40 years old because the general perception was that older people were unlikely to still be interested in comics. I used to see some younger attendees hold nasty opinions towards older people and felt bad about it. I’ve always wanted my parents to get a chance to go to a real Comic-Con. There are more and more conventions in China but the quality can not be guaranteed. Now, I usually make up excuses to prevent them from going when they want to attend one.

The Comic-Con in Chengdu is called ComiDay (CD) which is similar to CP, but with a much smaller scale. When I attended CD last year, the organizer set up a group chat with the attending artists. Some of them were professionals while others were amateurs. We talked a lot about exhibitions in China and shared our ideas, suggestions, and expectations. They really want to host the event properly and there are a large number of fans for CP and CD who are actively involved every year.

It’s impressive and not easy for CP and CD to last for so many years, trying to bring all the artists and fans together twice a year. CD is hosted close to me, so I try to support it whenever I have time. Our comic cons may not be as developed as in Japan, Europe, or the US, but only with support, will it make progress. And I always do what I can to support native events. The atmosphere in Chengdu is surely changing gradually. As you mentioned, there are two American comic book shops in Chengdu but none in Suzhou. If comic fans have chances to express themselves, I’m sure the comic market can make a big step forward.

Kristina Stipetic: Have you ever dreamed of creating your own original comic series?

Zhao Chunlin: Not really. I’m more like an artworker than a cartoonist, [Zhao Chunlin laughs]. Although most of my work is related to comics, I do other kinds of projects as long as they’re fun, like designing stuffed toys, mascots, postcards, T-shirt printing, and tattoos. I’ve done them all. I’ve always known that I’m not a good storyteller. I prefer to work with different writers and clients from various fields to draw something interesting and in different styles. I’d get bored if I had to keep drawing the same characters. I always want to try new things.

I mentioned Gorillaz before. One influence they had on me is that every illustration should be rich in detail. You can always find something amusing in it. I have the same demand for myself while drawing. I endeavor to make every drawing convey something and become a story instead of simply posing the characters in it even if I’m just drawing an illustration. I’ll be more than happy to meet people at comic cons who can find the Easter eggs in my works.

Kristina Stipetic: Anything else you’d like to add?

Zhao Chunlin: I’d like to leave my email address. Anyone who has read this interview is welcome to contact me for further communication and work invitation.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply