Unlike many other comic book writers, Mary Talbot did not start her career by being sucked into the world of comics as a child. She followed in her father’s footsteps and became a linguist. While her father was regarded as the foremost expert on James Joyce, Mary focused her own work on gender. Her textbook, Language and Gender is in its third edition and still widely used as an introduction to the topic.

However, she was never far from the world of comics. Her husband, Bryan Talbot, is considered the father of the British graphic novel. So, she was keenly aware of the process and promise of the medium.

After a distinguished academic career, Mary retired. Bryan suggested she write a memoir and offered to illustrate it. The book, Dotter of her Father’s Eyes, tells of the parallels and divergences of her own paternal relationship with that of Lucia Joyce and her father, James Joyce. The book was a critical success and won the Costa Award for biography in 2012.

What has followed since that publication is a series of books, set in different periods, filled with fascinating women. Some are actual biographies and others are well-researched, historically accurate fiction. All are about interesting, untamable women and tackle issues and themes close to Mary’s heart. The following is a quick run-down of her books:

Sally Heathcote: Suffragette uses a fictional working-class woman to tell the story of the fight for women to get the vote in the UK.

Rain explores climate change and mismanagement of the Yorkshire moors as the backdrop to a lesbian love story.

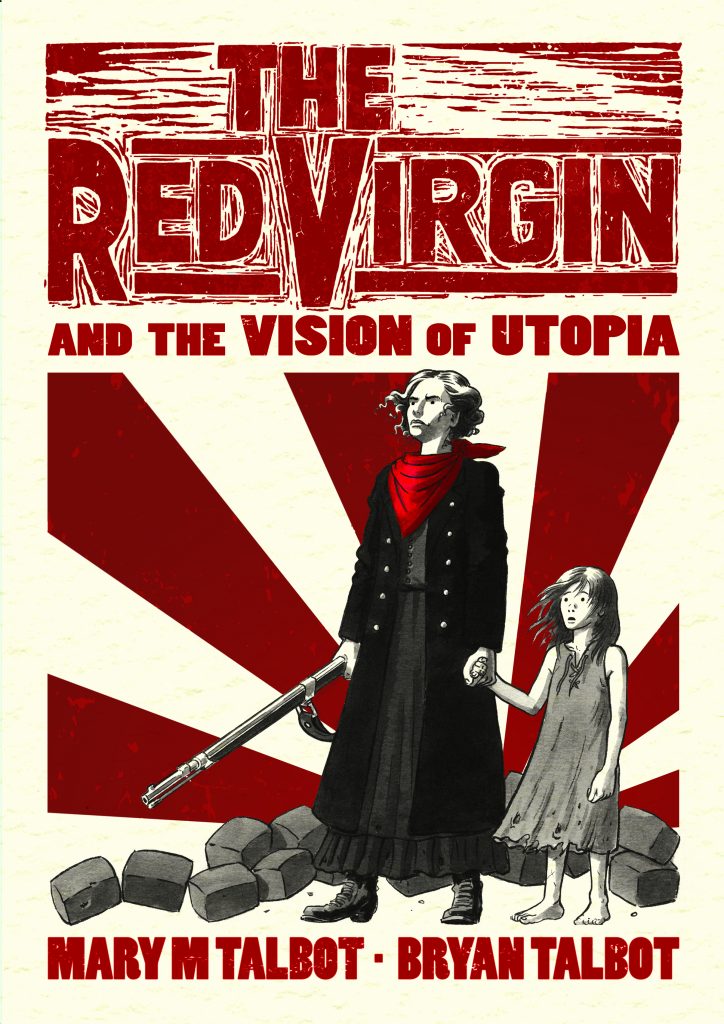

The Red Virgin and the Vision of Utopia tells the story of Louise Michel, the heroine of the 1871 revolt known as the Paris Commune, who was a champion of workers, women, and the colonized.

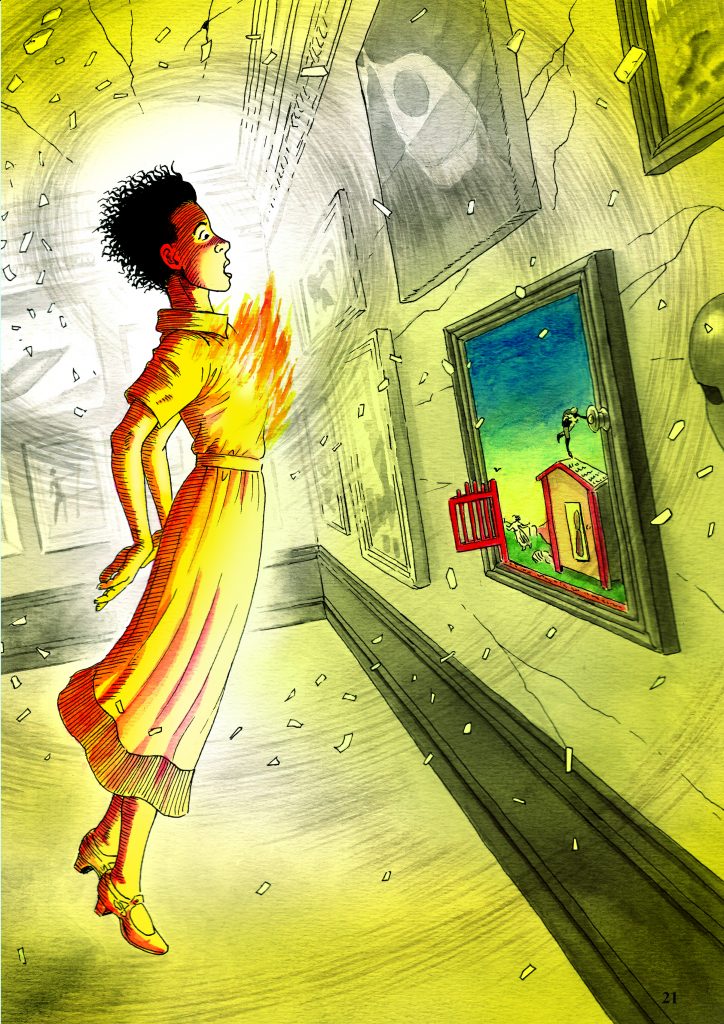

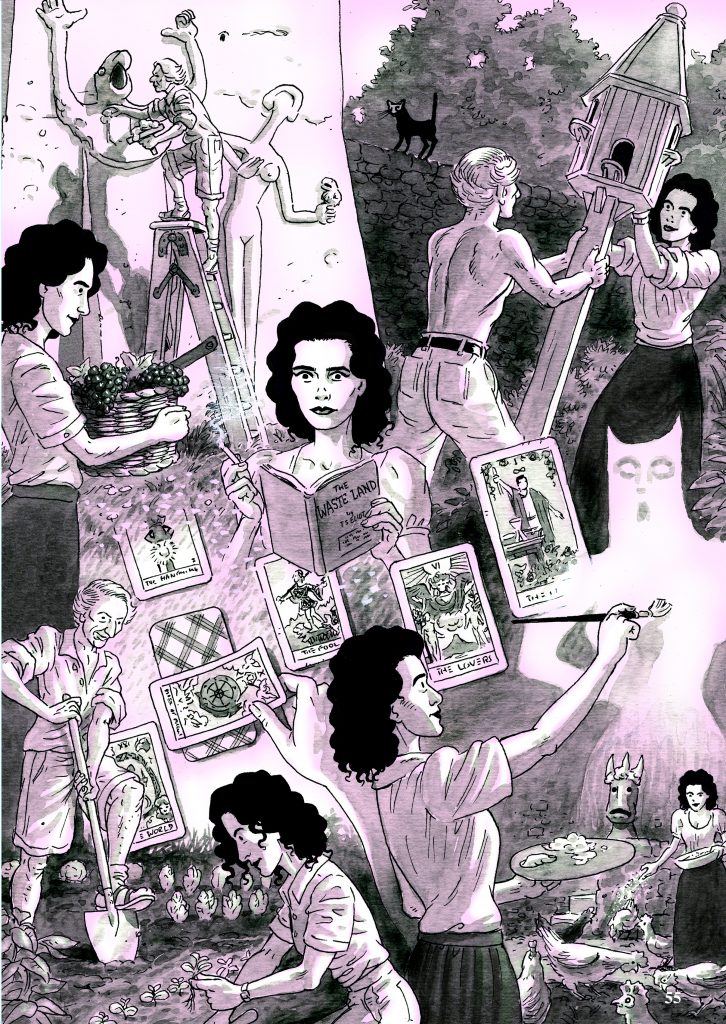

Her latest book, Armed with Madness: The Surreal Leonora Carrington, is a biography of one of the preeminent original surrealist artists. Leonora was another pioneering, untamable woman.

We chatted via Zoom in late May, just after the most recent book, Armed with Madness, came out.

TLN – So, the new book, Armed with Madness the Surreal Leonora Carrington, is amazing, I love it.

MT – Thank you. I’m really proud of it. I have it sitting on my desk here. (She holds it up)

TLN – I read it through once and then went back and gave it a second read referring to the end notes. They added so much context and fleshed out a lot of things. They are great, but very small print.

MT – They are really small, aren’t they? We got up to the space limit, the page limit for the print run. It would have been really expensive to do another sheet.

TLN – Right, because they start really huge and are folded into a certain number to be the size of the book.

MT – It’s done in sixteens, multiples of sixteen, apparently. Nine sheets printed to do the book. You can work out the maths. So, they were squeezing the end notes into a tiny space in the back.

TLN – Well, the book is gorgeous. The notes are great. It is a wonderful way to go through a second time and take it in with more information. There’s stuff that I, or any reader, brings to a book and will lead to more personal interpretations. Looking at the notes was great to have a fuller understanding about her actual situation or things that were being referenced and what inspired the images. That is always really interesting.

MT – Well, good. It’s the academic in me that insists on it. I can’t leave information out. Also, I want people to know how much work has gone into it.

TLN – I think it also gives people a place to look if they want to know more.

MT – Yeah, yeah. The thing is, when you’re doing biographical material, you can’t use all of it. It would be very ungainly. It wouldn’t make a very good story; it would be a baggy plot. It would go off on tangents and things, but I don’t like leaving gaps, factual gaps, you’ve got to fill them in somehow.

TLN – Your first graphic novel was a memoir, and your later books have that feel too – in that they focus on a theme or period of time and don’t set out to tell everything from beginning to end of someone’s life.

MT – Comics are the kind of medium where you can’t go into too much detail, too much length. You have to choose interesting sections. Unless you’re going to run into volumes and volumes.

TLN – I think you are also able to communicate with the artwork in a way that standard text doesn’t allow. There can be more emotion and more action told with fewer words. I think there is a balance and an interplay with that.

MT – I hope so, yeah. I would have liked to go on to say more about her later life. I mean it’s basically just about her early life and her escape as a refugee, with a little bit on the end that assures people that she had a rich and successful life, on her terms.

I would like to have space to spend time looking at what she did in North America and more about what she did in Mexico. She spent time in the Amazon with her patron, Edward James, who had this orchid farm or something, for a while. I mean there was just so much else in her life, she did all kinds of things. I couldn’t put it all in. I just went for the early stuff, which she wrote a lot about. Rather than relying on other people.

TLN – What drew you to her in the first place?

MT – Well, I’m always looking for a suitable biographical subject. Particularly since I did The Red Virgin. The big Louise Michel story, she was a really hard act to follow, you know. (laughs).

Since then, I’ve been reading around trying to find someone equally fascinating, who I could spend a lot of time with. Because these things take a lot of time. It has to be somebody who fascinates, because I’m going to be pouring over their life, so it has to be somebody who fascinated me and somebody I liked. I suppose that some people can enjoy being in virtual company with obnoxious people, but I can’t. It needs to be somebody I like, and I admire. I’m sure that there are a lot of them around, but there aren’t all that many of them around that you can find a lot of information on.

I was fortunate Joanna Moorhead brought out her biography of Leonora in 2017. I think I would have struggled to find sufficient material without that. I was looking into the possibility of Leonora Carrington as a subject, without her book I probably would’ve given up for want of more material.

TLN – What did you find most interesting or surprising about her life?

MT – The way she leapt into the unknown. Three times, four times. She was fearless, maybe foolhardy, in an admirable way. I couldn’t believe, astonished, at the way she could do such a thing. Confidence. I think that’s what impressed me about her. A lot of ridiculous confidence.

TLN – I think you may be seeing a kindred spirit. You’ve done a lot of brave, not reckless, but certainly more adventurous things. Off the top of my head, you’ve traveled in Morocco and New Caledonia, you entered a competitive academic field where your father was well known. Like Leonora, you raised two boys while pursuing a challenging career. You taught in Europe.

MT – Yes, in Denmark for 18 months or so. China too, though just for 5 weeks.

TLN – There is a theme that I see running through your work – that is the theme of “uncooperative” or “untamable” women.

MT – Oh, yes. (laughs)

TLN – Can you talk about that?

MT – They fascinate me. Maybe I admire them. I approve of the uncooperativeness, when I believe it’s justified. They are usually fighting against fathers. I can relate to that quite a bit as well, as you will know from Dotter of her Father’s Eyes. Basically, they are fighting against patriarchy in their own ways. The women that I’ve been interested in. Although Louise Michel was also fighting against capitalism and colonialism, all the “isms.”

Yes, strong female characters who have an independent spirit always fascinate me. Though I have to say, that’s not enough, I have to like them as well.

One woman, an Englishwoman, Gertrude Bell, rather aristocratic, incredibly intelligent, multi-lingual, and a major influence on the country of Iraq, but I hated her. I bought her biography and I thought she was loathsome. She wasn’t a feminist. She was a person who stuck up for herself, but it was all for herself. I didn’t get the feeling that she had any interest in the lives of other women. Quite the contrary, she always wanted to be an honorary man. In fact, she was made an honorary man by Bedouin tribespeople.

TLN – Emilie du Chatelet, she was a mathematician, she wrote about physics and natural philosophy – yet is often just footnoted as Voltaire’s girlfriend – was one of those remarkable, intelligent people. And at the time was honored with the notion that she was a man in woman’s body because she was Voltaire’s intellectual equal and a writer and creative and all of those things. Unfortunately, it ends up being this weird measuring stick that is kind of offensive.

MT – Yes. Yes,

TLN – Did Leonora have a specific diagnosis or was her breakdown more an enormity of circumstance?

MT – I don’t know if there was any sort of legitimate diagnosis. Psychosis. But it was clearly brought about by very extreme circumstances. I mean she was starting to fall apart as soon as Max Ernst was arrested and interned on behalf of the Germans. He was interned by the local gendarmerie, initially, as a foreigner, a German to boot. She was starting to fall apart, forgetting to eat, drinking too much and went into some very strange state, when she was found by her friends, and it continued to deteriorate as they were going through the troubled countryside. She was obviously very much aware that things were not normal. She imagined that was going into war-torn Spain, I think she was very much influenced by Picasso and other people who were very concerned about the civil war in Spain. As you see from the book, she saw Guernica when it was first exhibited, which was a response to the bombing of Guernica earlier in the year. So, this was very much in her head. I mean, there was a lot of pre-wartime anxiety going around.

Although she and Max Ernst managed to escape it. They sort of closed off the world and produced their own little fantasy reality. They had shut out the world, completely. They had a little idyll in Saint Martin d’Ardèche. Once that fell apart around her, that little secure haven that she had, it all just caved in on her.

And what was done to her, by various people, was in the name of her father, ultimately. When she was in the clutches of the people from I.C.I. in Madrid it was because of her father. As you’ve gathered, she was very much aware of “the fathers” coming after her. And having to save the world from the fathers.

I don’t know what the diagnosis was. I haven’t read anything which gives a clear diagnosis. But she was obviously a victim of the period which she was in. And the state that she was in.

Juana, my cat wandered by, mostly a tail on the screen.

TLN – Part of my surreal life.

MT – That was interesting. Octopus or cat?

TLN – It depends. (Both laugh)

MT – I think schizophrenia was the term that was used most.

TLN – It wouldn’t surprise me. My late mother-in-law was schizophrenic.

MT – Right.

TLN – So, I have some small familiarity with symptomatic things. It is very interesting because it does allow for a kind of creativity, it allows for a kind of imagination and an ability to view the world in ways that can be expansive. But at the same time, it also comes, often, with paranoia. Which results in shutting out as much as imagining. Once the idea of pursuit or persecution gets embedded it can be very hard to overcome.

MT – Leonora was always a bit strange. There is nothing ordinary about her. She wasn’t the most easily sociable person. She didn’t get on with people. I don’t know what kind of condition that is.

TLN – Judging from her story I think a lot of that is people wanting to stuff her into boxes, and for her to be what she wasn’t. You know, her family wanted her to be a debutante, not an artist. Trying to pawn her off in marriage primarily to secure more status for the family.

I think another piece of the mental illness question has to do with being untamable or uncooperative. That a lot of the “treatment” isn’t about actually fixing anything in the person, it is about making them docile or containable.

MT – Right. Yes. Madness was weaponized, certainly in the 1930s. Madness among women was weaponized. People were incarcerated for life on the basis of less. Less than what Leonora did. Lucia Joyce is a case in point. And she did not escape.

I rather wanted to have an escape story of somebody who was incarcerated. I think that was an element, you know, because poor Lucia spent almost all of her adult life in mental institutions. It was such a joy to read about Leonora’s life. She escaped and had a creative life, had the sort of life that she wanted. That’s one reason I wanted to write about her. It was a story of women’s incarceration that had a happy ending. (Smiles) For a change.

TLN – I know someone who was institutionalized in, I believe the mid-seventies. She wanted to get out but wasn’t getting anywhere, and she managed to get ahold of her file. She found out that one of the things they were judging her relative sanity on had to do with her interest in her appearance.

MT – Oh.

TLN – And so when her family would visit, she started asking, “Could you bring me some lipstick.” Or “I think I need a new brush for my hair.”

MT – So she was doing this tactically.

TLN – Yes. She understood that they saw her taking an interest in her appearance and focusing on being more “feminine” by being more concerned about fitting in socially as a sign that she was getting better – or at least more manageable. So, over about six weeks she started making sure that she wore makeup and was concerned about her clothes being clean and it went a long way to her getting to go home.

MT – Gosh, yes. I wonder if that’s what Leonora was doing in Lisbon. I hadn’t seen it specifically like that, when she was trying to think of a way of being able to get into town so she could escape. Maybe the choice of looking for gloves to look after her hands in the hot weather. The things that she said she had to have. She couldn’t possibly go on a cruise on the ship at sea, without a hat and gloves.

(Both laugh)

TLN – You deal beautifully with the sort of varied relationships between women in this book. Leonora, as the mistress with both Marie-Berthe, Max Ernst’s first wife, and Peggy Guggenheim, the would-be second wife at that point.

And also, her relationships with the girls at the Ozenfant Academy, where it seems that they have a real bond of friendship based on mutual interest and creativity.

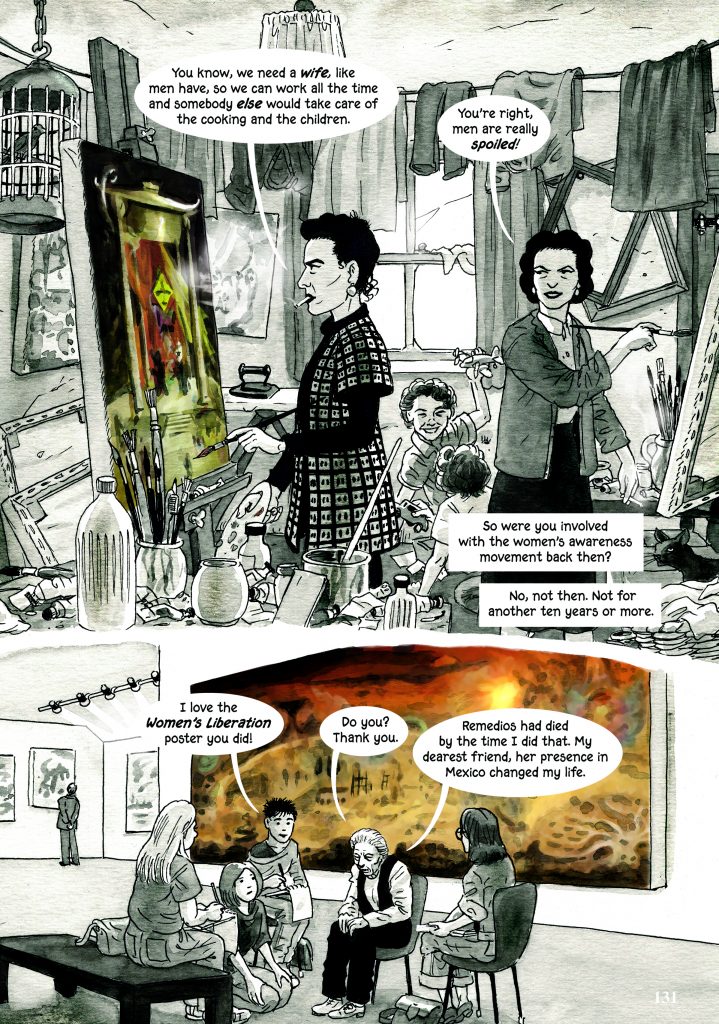

Later that plays out in a much fuller relationship with Remedios Varo in Mexico.

MT – Yes. Remedios becomes her working partner, I mean they worked alongside a lot in Mexico City. She states how important that relationship was for her in the later part of her life.

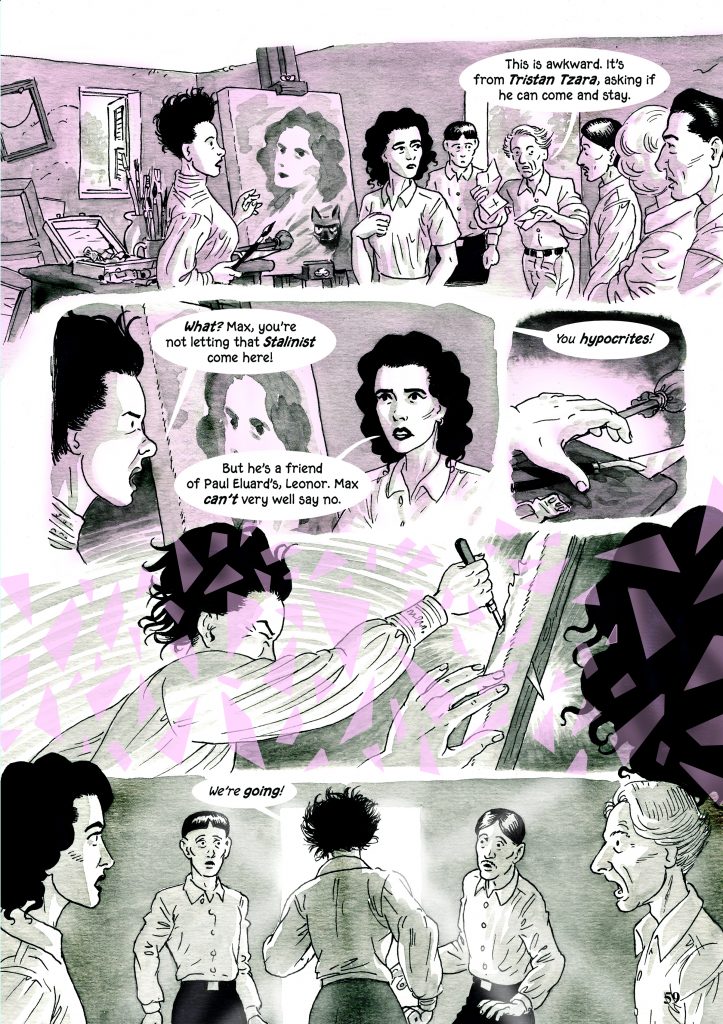

She seemed to value female friendship. The other Leonor, Leonor Fini. They had a falling out, although it was basically over what was a men’s argument over whether to

Support Trotsky or Stalin in the International. (Both laugh) Woof. They had a falling out over that, which obviously I included in the story because it is so dramatic. Fini did actually take a palate knife to Leonora’s portrait. But they remained good friends afterwards. They corresponded for a long time. It didn’t end there. And she was very important to Leonora, which is why she was so hurt by this assault – virtual assault – on her portrait.

I think, in terms of creative people, creative women, she valued the friendship, but she didn’t seem to go out of her way to make friends with schoolgirls when she was at school. It was only with people she was interested in.

TLN – It seems like the art connection is very important and I think that with women she had the opportunity to be a fellow artist and was never cast in the role of muse.

TM – She appreciated learning from men. Obviously, she had a very positive, short lived relationship with Max Ernst. She obviously got a lot out of it, as well as possibly being exploited by him. We don’t know. We really don’t.

But I think it was the female relationships that she valued the most.

She doesn’t say a great deal about her relationship with Chiki (Imre Emerico Weisz Schwartz, her second husband.) She obviously got on with him okay. Though I think they lived partly separate lives, most of the time they were both alive. It wasn’t a very conventional marriage, I don’t think. They had two sons, of course, who she adored.

TLN – The surrealists were very much about throwing out the rulebooks and having a more open vision but somehow that often fell short when it came to women – can you talk about that a little? What did that mean for Leonora Carrington?

MT – She used to say she didn’t have time to be anybody’s muse; she was too busy learning how to paint. I’m not sure how seriously she took the proclamations of the surrealist circle in Paris, with André Breton as its self-appointed leader. By her own account, she never read the Surrealist Manifesto. That sort of answers your question, I think.

TLN – I don’t know if this is just a function of your focus in the book, but it seems like her mental health is much improved in Mexico.

MT – You don’t hear anything about any mental problems when she’s in Mexico. But maybe that’s because she’s no longer being pushed around by anybody. Who knows. We only have what her biographers and herself have to say on the matter, don’t we? She seemed very settled. Apart from things like the upheavals in ’68, when she ended up having to flee and lived in the United States for quite a few years. Which must have been difficult for her. Incredibly difficult with leaving family behind. But I haven’t seen a great deal written on that, so there’s not an awful lot to go on. Maybe I’m just looking in the wrong places.

TLN – I’m feeling like so much of it was so circumstantial, and when she got into a place where she’s more secure and was really allowed to create on her own terms, a lot of that pressure was released.

MT – (Nods)Mm.

TLN – There might still have been things in her head, and not that she wasn’t fanciful – I’m thinking about her drawing on the walls for the kids and telling stories. There is a sense of all of the stuff that might be classified as mental illness being channeled in a way that it was not debilitating like it had been in Europe in the war years.

MT – Also, she took a lot of interest in very spiritual things. She studied Buddhism, for example. She probably found a lot of peace doing that. That isn’t something I’ve given any space to in the biography, perhaps it could have done with a word or two, but I think probably doing her own kind of research in her own time, gave her a lot of peace as well.

TLN – I don’t know if it was in the book or if I came across it someplace else. But somebody wrote that Mexico was the perfect place for her to go because it is somewhat surreal.

MT – (Laughs)Yes. She felt much more at home. I think she enjoyed the local people, the native people. I can’t remember the name of them at the moment. She spent a lot of time researching for the wonderful mural she did for the museum in Mexico City. She did a lot of research, going and visiting villages. Not on her own, but with a couple of other people. She really enjoyed that kind of exploration of her new country.

TLN – What excites you most about Leonora’s work?

MT – It’s hard to pinpoint any one thing. She was prodigiously talented and hugely prolific. I think perhaps it’s the way she communicates her love for, and affinity with, non-human life. She was after all “mostly a horse”!

TLN – Do you have a favorite book or piece of work of hers?

MT – I think I like her sculpture best, actually. Her later work, I suppose. But some of those sculptures that she has down Paseo Reforma in Mexico City, they are just extraordinary. I wish I could go and visit them. I’m not going to go to Mexico, I’m afraid. It’s too far.

TLN – Do you ever find yourself embedded in the research process and having a hard time getting to the writing?

MT – Not so far. There comes a point when you say, “Oh yeah, there could be a good story, starting just there,” And that’s when I start to roughly sketch out what might be the ordering of the storyline. I still carry on doing the research, but with a sense of where the incision is into the material. It’s quite an important point in time for me, actually in terms of deciding whether it’s going to work. Whether it feels as if it’s going to be a good story or not.

With the suffragette book (Sally Heathcote: Suffragette,) it was a crisis point within the leadership of the women’s social and political union. I thought Crikey that’s a good, exciting place. Everything’s all going to start to hit the fan after this point. That’s going to be a really good way of opening.

TLN – It’s funny. One of my questions about that book was: One of the interesting elements of this story is the factions that develop within the movement and the different ways they sought to move forward, to change laws, to change public opinion. I thought that was a very interesting human element to political reality. Even when united in a cause it is sometimes hard to be moving forward with no lockstep. I was wondering if you could talk about that element of the story, and you just brought it up.

MT – I think it’s important if you are talking about a group of people who are trying to bring about social change, you’ve got to look at the struggles they went through internally as well as the struggles they were fighting outside. Because they are always there. You can’t pretend, you can’t idealize social movements. You’ve got that they are inevitably they’re usually, at least the left-leaning ones, are constantly in a state of turmoil. (Laughs) I’m thinking what the British Labour Party is like at the moment. What they’re always like, when it comes to that. What the International was like during the 30s. The in-fighting. Do you support Stalin or are you a Trotskyite? And then falling out with one another.

TLN – I think it’s quite a shame that Stalin came out on top of that one.

MT – Ahh, just a little, yes. Of course, Trotsky was assassinated at Diego Rivera’s house.

TLN – I also noted that with Sally Heathcote you did a composite character, not based on a specific historical figure. She is surrounded by lots of well-known historic figures. I was wondering if there was a particular reason to use her as a vehicle, rather than picking an actual person as you have in most of the other books?

MT – She was a fly-on-the-wall figure originally. I mean there was a lot more I could do with a figure like that rather than selecting one biographical subject and focused on that. It enabled me to go much more widely around the movement. Also, it was important to have a working-class person much more central than I would have been able to do otherwise. There obviously were a lot of working-class rank-and-file figures in the movement. One wrote an autobiography, Hannah Mitchell. But it wouldn’t have given any kind of scope at all. It would have limited it to her perspective, in the North-West of England, mostly. Having a figure like Sally, who was much more mobile, and also had the benefit of not existing. Which meant that I could make things up. (Laughs) And take her places, you know.

But I wanted it to be very clear. Something which struck me amazingly, when I started researching the suffragette movement, just how huge it was. It wasn’t just middle-class, as people tended to assume, because of the prominence of middle-class figures. It was all across the social spectrum. Aristocratic people, of course, but also rank-and-file women. Lancashire textile workers, most of whom were women, were the foundation of it. That was also the foundation of the Labour Party, as a matter of fact. I wanted it to be something that could take in that whole range, different social classes. And having Sally Heathcote allowed me to do that.

TLN – One last thing on Sally, I hate spoilers, but I find the ending to be heartbreaking.

MT –(Sighs) Oh yes.

TLN – Do you think people take the responsibility of voting for granted?

MT – Well, to be fair, it’s getting difficult to take voting seriously, in the British context, because it’s less and less effective. I mean without proportional representation the voting is so skewed. For a lot of people, they might as well not bother. That’s not what I said at the end of that book, but I can understand people feeling disenfranchised, when in effect, they are in a lot of places.

TLN – Here as well. The amount of gerrymandering, creating districts that are shaped in such a way that it is not possible to dislodge a particular party. Which means that people are really not represented because their vote is divided up and kept from having any kind of a block when there is a much larger left-leaning group.

MT – Yeah, proportional representation is probably the way out of it, but there isn’t any motivation in the places where it matters in Britain. On a grand level motivation and pressure for it has been increasing but it is not having any effect on the leadership. Noticeably.

TLN – Perhaps the leadership is afraid that it will move them out of leadership.

MT – Could be. (smiles)

TLN – So, in RAIN. I know it was inspired by the unprecedented flooding in Yorkshire and the mismanagement of the moors. Has anything been done to restore the moors and improve the situation?

MT – (Laughing) There’s some revolting looking, great concrete flood barriers, though whether that’s an improvement or not. You can’t see the river anymore when you’re driving up the side. There are lots of people who piled money into the local businesses so that they could reopen, because they could no longer get insured anymore. The local comic shop, Two-Tone Comics I think, we donated lots of artwork for them to auction, so they could open their doors again. That kind of thing has been going on since… (She shrugs and shudders) how many years ago? It was 2015, Christmas. Eight years.

TLN – It was funny, when I was reading the book, I kept thinking there was going to be a tragedy for the main characters and was very glad that it didn’t end as I feared.

MT – Even the cat survives. (Laughs)

TLN – Save the Cat. But unfortunately, the real tragedy sort of happened with Brexit and the US election in 2016.

MT – When I was writing that, the sense of irony wasn’t there. The irony came later. I tweaked it at the end to bring in the sense of irony.

TLN – I love the quote from Alexander Van Humboldt at the beginning.

MT – Wasn’t he amazing?

TLN – Tremendous foresight. And understanding about how things really work.

MT – That was a very late inclusion. Thanks to his biographer, Andrea Wulf. We were in the Edinburgh Festival promoting Red Virgin and she was promoting her biography of Van Humboldt. And I thought wow. This character is fantastic. I’m going to have to include him somehow. Because he was, you know, so foresighted. He predicted climate change in 1800.

TLN – Which is just phenomenal. On another weird side note – my specialty I guess – there is a theory that the impressionist painters painted that way because there was so much smog and particulate matter in the air that everything did really look that blurry at a distance.

MT – Perfectly possible. Probably partly eye problems as well. Between all of the muck in the air and macular degeneration or something.

TLN – Going back to your work, Louise Michel, the subject of The Red Virgin And the Vision of Utopia is a staggering story and yet she is virtually unknown in the US. Is she better known in the UK?

MT – No. (shakes her head). Only amongst, well left-leaning people. We met Jeremy Corbyn at the same Edinburgh festival. You know the former Labour leader, too left. Too left by half. We gave him a copy of The Red Virgin basically because he said he’d heard of her. Not many people have. We asked, “Have you ever heard of Louse Michel?” “Yes, of course.” Responding as though it were a silly question.

People very much to the left of center will have heard of her because she was a heroic figure. People who have read up on workers’ history, in Europe, know who she was. For anarchists, she’s a sort of patron saint, if that’s not a contradiction in terms. She’s a sacred figure to anarchists. They would know who she was.

TLN – Why do you think her story is not more celebrated?

MT – Because of what she stands for or stood for. She is this icon of the uprising of trodden masses. She was also, God help us, a feminist.

TLN – She is kind of the complete package.

MT – She was also an anti-colonialist. How much worse can you get?

TLN – I see in my notes that she was another woman who was “uncooperative,” her calling being social justice. Can you talk a little bit about what she accomplished and what she suffered for it?

MT – She refused to swear allegiance. Which meant that she was restricted professionally as a teacher in France. So yeah, she was another rebel woman. She spent her life fighting for the rights and dignity of working-class people, both in her native France and in the French colonies of New Caledonia and Algeria. She was deported to a penal colony for seven years and imprisoned over and over again after that. Unstoppable.

TLN –Her life is truly inspiring, especially what she accomplished in New Caledonia. She was an exile, but she learned the local language and fomented rebellion against the colonizing occupiers.

MT – That the French don’t know about. It is the only book of our collaborations that has been translated into French, so far. And it was partly on the strength of that, the amount of detail of her life story that’s in there, that French people don’t know about. I mean she has a name on public buildings, a couple of hundred schools named after her, in the French-speaking world, including one in New Caledonia, I think. But they don’t really know much about her.

TLN – Sort of getting to first things last, what inspired (drove you) to not only do a memoir but to do it as a graphic novel?

MT – Not long after I retired, it was Bryan’s suggestion that I write a memoir and he would illustrate it. I was flattered, both that he thought I could do the writing and that he was offering to draw it. That’s not to say I felt sure about the idea, at least not at first. Who would want to know about me? etc.

TLN – Apparently quite a few people. I think it’s the only graphic novel to win the Costa Award for memoir.

How does being a linguist influence your graphic novel writing?

MT – With the dialogue mostly. I did a lot of discourse analysis, so masses of transcription of naturally occurring talk – the hard way before there was auto-transcription! Doing that gives you a pretty good sense of how people actually engage in conversations, rather than what people think they do. But I’m not going to launch into a lecture on ethnomethodology and conversation analysis here…

TLN – One last thing and I will let you go. What are your favorite comics or graphic novels? Who are the artists or writers you really look forward to reading?

MT – I always look forward to reading the next from Posy Simmonds, and from Oscar Zarate too. And of course, Bryan! Bad Rat and Alice in Sunderland are the best! But there’s so much out there now – it’s hard to choose. Alison Bechdel’s Funhome is beautifully crafted. I love Simon Hureau’s L’Oasis: Petite genèse d’un garden biodivers, because of the subject matter, but the art is delightful. From Germany, I’ve read in translation Barbara Yelin’s Irmina and found it extraordinary. Scarlett and Sophie Rickart’s adaptations are excellent: No Surrender and The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists so far. The first reworks Constance Maud’s novel about the women’s suffrage movement, published in 1911. The second is Robert Tressell’s classic, published posthumously in 1914. I think the Rickart sisters are currently working on another. I’d better stop.

TLN – Thank you so much for your time. Wishing you the best of success with Armed with Madness: The Surreal Leonora Carrington.

MT – Thank you.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply