Without much exaggeration, it can be said that the inborn instinct of citizens of the great Western Empires is that the rest of the world is both their playground and their property. Without invoking too much sanctimony, it can also be said that much of the Western artistic tradition follows the same line of thinking. Common knowledge, I suppose; however, there are thorny conversations to be had about whether or not the narrative representation of this fact is correctly positioned from the standpoint of a citizen of the Western imperial project. Many people legitimately enjoy Aguirre: The Wrath of God or Fitzcarroldo for their presentation of the project of colonialism as fetishistic and extremely violent, while some have critiques of this project coming from those descendants of empire. Basically, there’s a divide between the acknowledgment of the facts and the implementation of a premise. How effective can it be? What’s there to say and what ground is there to cover that hasn’t already been iterated by other people who have benefitted from this project in one way or another, directly or indirectly, explicitly or implicitly? To be slightly reductive, it’s mostly likely a matter of taste, that is, whether you enjoy colonial exploitation as a premise to be explored by a comedic graphic novel.

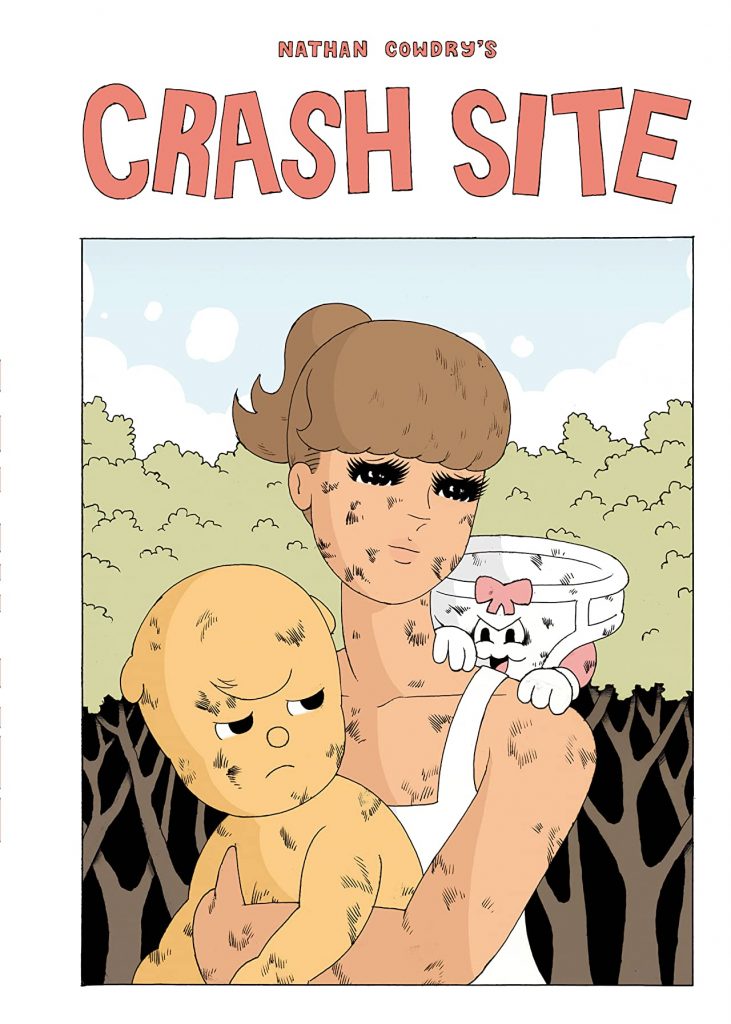

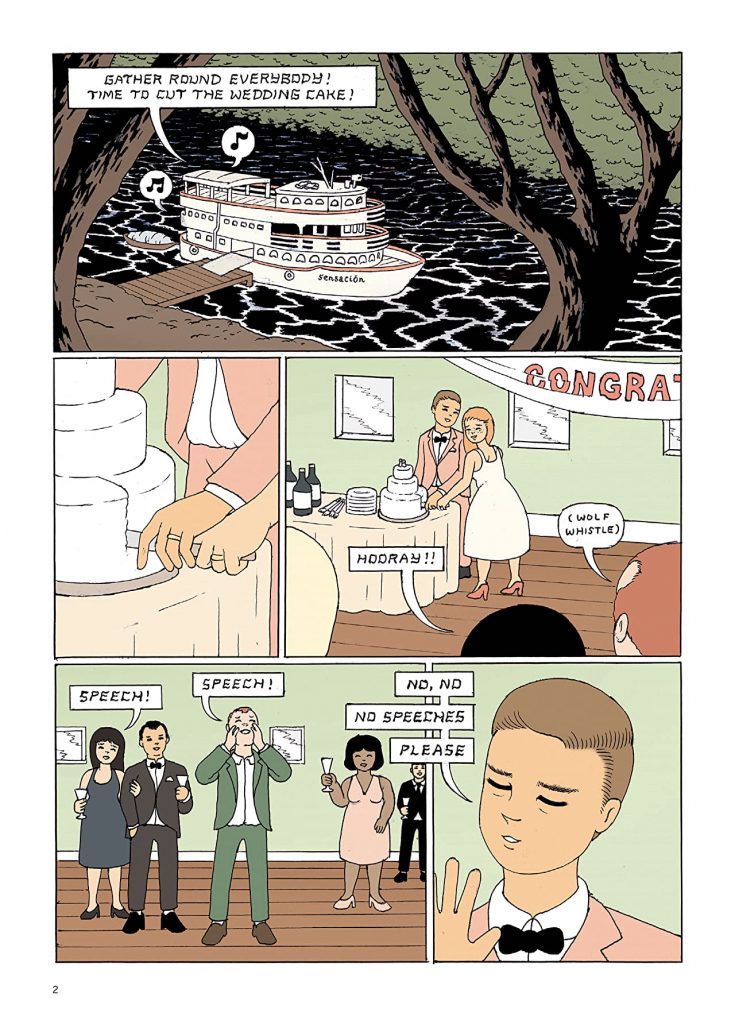

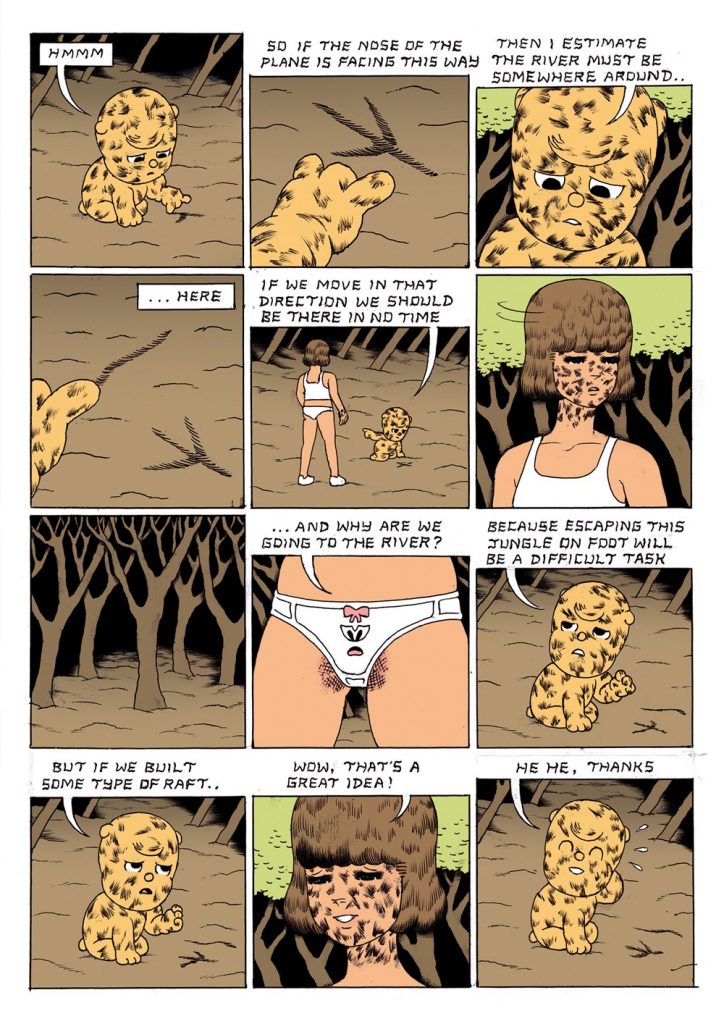

Crash Site by Nathan Cowdry follows the trio of Rosie, Denton (a dog), and Pants Dude (Rosie’s panties) as they go on an expedition to South America to smuggle drugs back to the United Kingdom. Denton is being used as a mule by Rosie, whom he is in love with. The narrative, for the most part, takes place as a flashback delivered by Denton to a detective investigating narcotics trafficking in Bogotá. Over the course of Denton’s narration, he discloses that they were on a plane that crashed over the Amazon, that they were the only survivors, and that in their ensuing journey to be rescued there was a conflict between himself and Pants Dude for Rosie’s affection that culminated in Denton being disemboweled. Pretty gnarly stuff. Plot critical events, however, represent the least interesting aspect of Crash Site. More significant is the conversation that it’s having with the subject of imperialism and how people interact with it. Explicitly: how white people interact with it. After the crash, Denton passes out in the jungle. He has a dream that he and Rosie are in Vietnam violently murdering members of the Viet Cong. It’s a canned sequence, and I think there’s good grounds to say it’s intentionally laid out this way. In a facsimile of every Vietnam movie ever made, enjoyed, and critically acclaimed (racial slurs included), the reader gets a sense of Rosie and Denton’s imperialist unconscious. They’re not even in Vietnam – they honestly don’t even know where they are. It’s fair to say that they don’t even care. Their instinct is violence. The book’s opening is, as well, a reiteration of thematic critique of Imperialism and Culture Tourism – an awkward sex scene between two Christians celebrating their wedding on a river-boat tour of the Amazon River where they met “on a mission trip to provide aid relief to the savage tribes of this land.”

Which is all to say that Cowdry’s opinions of the characters of this book are quite explicitly stated. They are all opportunists in one way or another. Denton is incredibly horny and Rosie is a vapid materialist. Truly the only people with much dignity or sanity to speak of are the characters native to the region, albeit they only speak sparingly and essentially only serve as instruments to move the plot along. The most significant among these characters are Detective Barrero and Prince Puju who have small roles that are pretty trope-centric and marginally considered. All that Cowdry seems to want to communicate with these characters is that they are nowhere near as perverted as Rosie or Pants Dude or even Denton. There’s a strength to this, however, as there is very little room for the plot to become confused or for the audience to have any conception of why exactly the central characters are so deplorable. Simply, they’re British. But Denton and Rosie don’t know they’re awful. They don’t even care enough to think about what they’re doing. As far as they are concerned, it’s a victimless crime and the adventure of the whole thing is romantic enough. To Rosie, it’s kind of sexy that she’s traipsing around the globe and making her dog swallow a brick of cocaine to get through customs. She brags about it to all her friends in one sequence. What else is she going to do; get a retail job? Even after the crash, after Denton has been flayed alive by Pants Dude, and after she’s survived being deathly ill in the jungle, Rosie hardly reflects on the ill-conceived nature of this entire venture. In the Nabu village, she falls in love with Prince Puju and tries to get him to come back to the United Kingdom with her, only later for him to be violently murdered by Pants Dude as they are rowing down the Amazon River. It’s somewhat unclear if there’s any realization that she will eventually come to, and that is appropriate for what we know about the character.

The small details, as well, are quite nuanced and pointed at the effects of Western culture on the minds of its citizens. Rosie religiously watches Britain’s Got Talent, Denton masturbates to pornography that’s intentionally racist to sexually excite people who self-identify as “woke,” Rosie beats the shit out of a lifeguard on the beach for making her put on clothes, people wear Korn and Counting Crows shirts, etc; there are many other examples of these kinds of details that express the conclusion that Western culture is inherently perverse. To be sure, the visual style itself is a send-up to the history of Western imperialism in comics. Everything is sharp and clean. The characters look like enamel pins or old-style Disney strips. Both narratively and in the clear-line style trademark of Hergé, the comic is a contemporary Tintin. It is, after all, a colonial romp between a human and their dog. And, finally, the characters all look uncomfortably pre-pubescent. Complete with bobbed hair, baby-doll faces, and suspiciously uniform breast sizes, Cowdry’s female figure is discomforting in all of its hypersexualization seen throughout the piece. Holistically, there’s enough thematic information for this to be interpreted as an extension of the perverted nature of the Western imperial project and, of course, the Western canon of comic books as it serves, protects, positively interprets, and fortifies this project.

If the question is whether Nathan Cowdry’s Crash Site is defensibly aware of the implications of its narrative, whether there’s enough narrative technology at work to bring us to the conclusion that the project of imperialism is deplorable (as seen through the author’s eyes), then the answer is definitely yes. The final scene is quiet. Rosie is playing a first-person shooter game set in Vietnam, presumably where Denton got the inspiration for his dream in the earlier sequence, and she pauses to go to the bathroom to rub her eyes where she looks in the mirror half-heartedly. She returns to her bed to sit in the dark and murder virtually rendered Vietnamese soldiers. The final panel of the comic is a question: “play again?”. The cursor is hovering on “yes”. Whether this occurs before or after the expedition to South America is unclear. The last the viewer sees of Rosie is aboard the raft with a murdered Prince Puju and Pants Dude. But it doesn’t matter. Will the colonial project reiterate itself again, again, again, and again? The answer is also yes.

If there’s a justification for books like Crash Site it’s that the project of Imperialism is forever ongoing, and if those who are inundated with a culture that serves, protects, positively interprets, and fortifies this project are asked the question of whether they will do it again, the answer will always be yes. It will look different in some ways, and there will almost certainly be different manners of speaking to verify this project, but ultimately the answer will always be yes. And I agree, personally, that the answer will be yes. If that is what Cowdry is saying with Crash Site, I agree. Whether the positionality of the person asking the question inhibits the veracity of this question, its violence and horrifying perversion, is difficult for me to say. I, as well, am probably not the right person to ask, or the right person to interpret the question. All I know is that we both benefit from the structure, despite our awareness of it, so I hesitate to bestow too many accolades in acknowledging the disgusting core of the imperial project. The question Cowdry is asking in Crash Site is pretty thoroughly considered. It is defensible. Whether you’re interested in defending that is, again, up to you. As I said, I am the wrong person to ask.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply