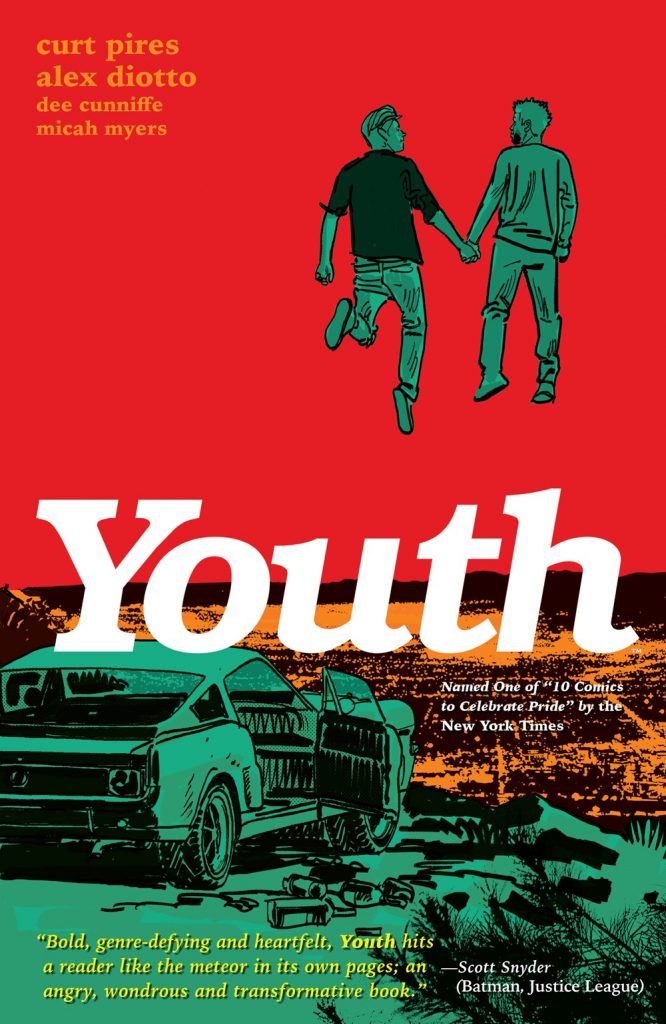

With one look at the trade paperback of Youth by Curt Pires, Alex Diotto, Dee Cunniffe, and Micah Myers, you could be fooled into thinking that Dark Horse is getting into the universe-building game (again). I rarely find myself gravitating towards a book that “redefines the teen superhero story,” as promised by an errant blurb on the back cover, but I’m a sucker for good cover art. On that account, Youth delivers with a striking view of two young men holding hands, rendered in green, floating in a skyline colored the deep and violent of fresh blood. It’s a portent of things to come — Youth is an exceptionally bloody book, framed around those men and their shared future.

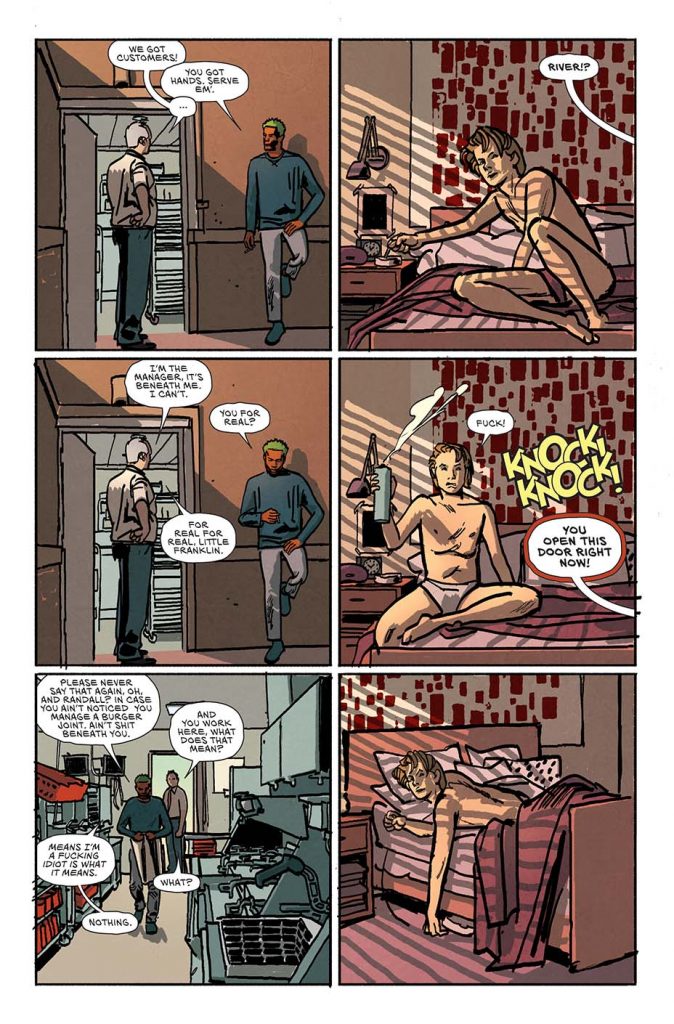

Now, stop me if you’ve heard this before. Youth starts with two young Midwestern men, Frank and River, being berated by older white guys. Within the first seven pages, both Frank and River have thrown a punch at said older white guy, dramatically changing their personal trajectories. After stealing his stepdad’s Mustang, River invites Frank on a road trip out of nowhere and off to California – the two are lovers on the lam and it seems like everything is going to be perfect. Things don’t work out (do they ever?) and the pair join forces with a small crew, crash a party, run from the cops, and subsequently get hit by an asteroid which gives them superhuman powers.

Yes, it’s not the most original introduction, but the writing at least feels like it has a pulse, which is something you can’t always depend on from publishers like Marvel and DC these days. That said, it would be a bit of a farce to separate Youth out too much from the Big Two — because this book is just as corporate. Dark Horse is the publisher of the trade paperback, sure, and, on my initial read, Youth seemed like something that could easily fall inside their wheelhouse. But imagine my surprise when I found out that this book is actually a ComiXology Original, and it was already optioned to Amazon Studios before the first issue ever hit (digital) newsstands. So… am I reading a comic book or someone’s storyboards? Is Youth a story created to exist as a comic first and foremost, or is it just tryouts for another medium?

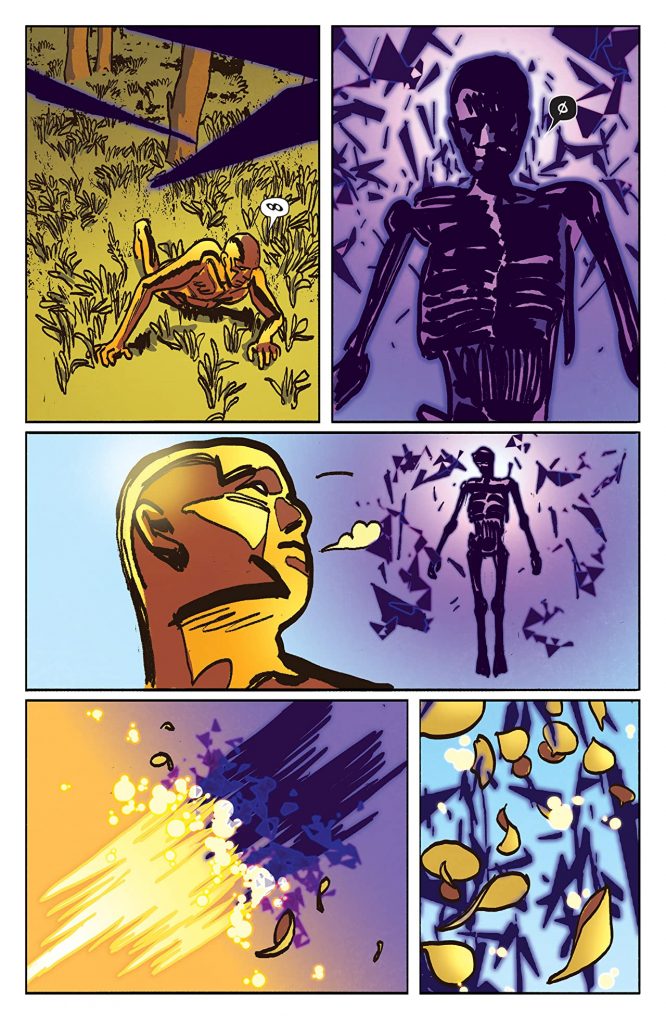

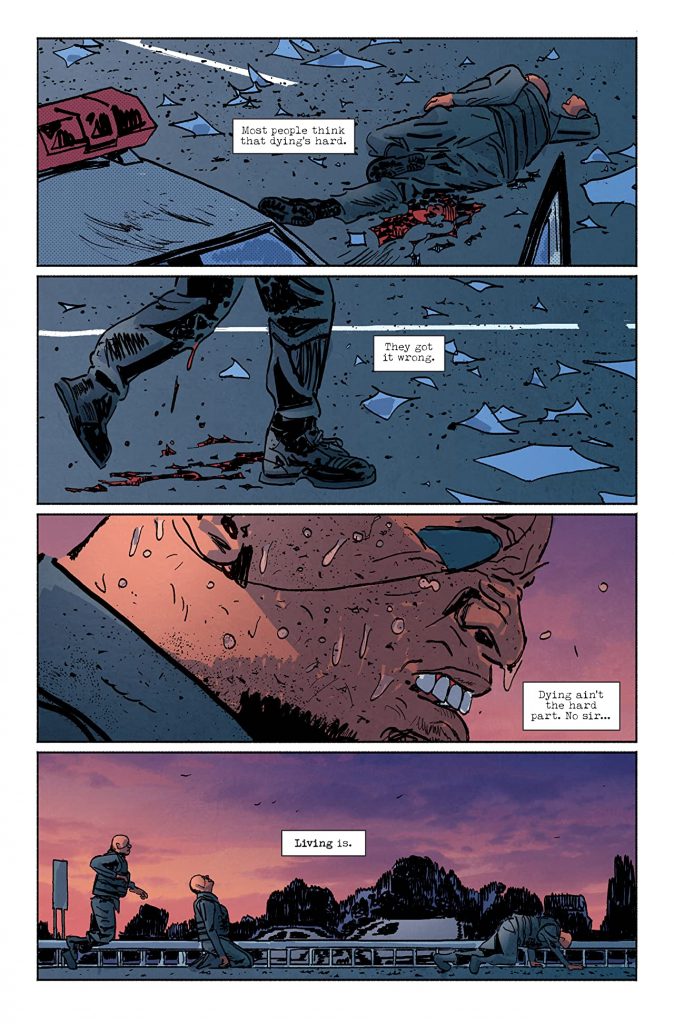

Those questions largely remain unresolved throughout Youth because, in some ways, the book feels even more commercial than Marvel’s X-Men, which, if nothing else, has a batshit crazy energy to go along with its implausibility. While I said earlier that the writing of Youth feels like it has a pulse, that is mostly because of Pires’ familiarity with natural-sounding dialogue. On the other hand, the plot of Youth is flimsy wicker patio furniture caught in a tornado. It is the barest of beats made somewhat more interesting by the choice to tell the story through a series of reminiscences and flashbacks. Dee Cunniffe’s colors bring vibrancy and life to Diotto’s heavy lines, although everything in this book, minus the cover and a few beautiful splash pages, looks rushed. Diotto’s figures often look “off-model”, and sometimes you can see the pixel width of the Photoshop brush that Cunniffe is using to apply color to the page. Micah Myers offers a reasonable if unremarkable lettering job. The best you can say about the art throughout the book is that it recognizes the strengths of comics as a medium of subtraction, yet it still feels like a solid, if workmanlike effort.

If the dialogue feels alive, then the characterization is its polar opposite. This feels particularly egregious because Youth seems to be written exclusively to reference famous actors or widely known tropes in its characters — Frank, meet Frank Ocean; River, meet River Phoenix. These references are occasionally made textually, so it’s clear that Diotto is using these real people as his visual references for these characters. While I’m sure that there’s fan fiction somewhere of Frank Ocean and River Phoenix making out, seeing it in color on the pages of Youth feels both perplexing and slightly offputting.

Perhaps what is most awkward about these real-person references, though, is the storytelling choices that Pires and Diotto put these two young men through — turbulent family lives, bigotry and hatred, petty and grand theft, and, finally, a “Bury Your Gays” ending that can be seen coming a mile away. Using the likenesses (and names) of two men, one of whom is gay or bi, and the other who died of a drug overdose after playing a gay man in a movie, feels gross, for lack of a better word, especially after the fourth issue, where River goes down on Frank in a flashback and then gets murdered by the military junkhead “Don Thunder,” a textual riff on Nick Fury from the Marvel cinematic universe. That’s a darkness that is neither earned nor consequential, since the main antagonist, the American military, is completely toothless through the vast majority of the comic, except when it’s killing the gay kid.

If we put the ending to the side and ignore that it exists for a few minutes, I do like that the focus of the drama and energy in Youth comes from the frazzled relationship between Frank and River, the characters who throw those introductory punches. They’re a couple, at least initially, planning to run away and start a new life together. The world revolves around them, as does the entire comic. These two characters, in all their messy glory, are the beating heart of Youth. In the second issue collected in this book, an unnamed pair of supernatural beings, one of creative infinity and one of creative abyss, bounce off of one another while creating and destroying a universe which is what ultimately leads to the asteroid strike that gives all the teens their powers. In these two opposing forces, it’s easy to see a corollary in the two young men who create and destroy their relationship throughout this book.

As for the other characters in Youth, though, they’re basically cardboard cutouts that exist around Frank and River. This supporting cast exists to get Frank and River from place to place or to introduce some friction into their relationship, but not much else. For example, Frank has the tendency to take ecstasy and get horny. This doesn’t usually go well, and Frank ends up in compromising positions with the manic pixie dream girl in the group (named Trixy, natch), often in places where River can find him. Initially, this is frustrating for River, but once everybody is suped-up on asteroid juice, bad things start to happen.

This flimsy supporting cast is indicative of a trend in this book, where things are approached and then left at a surface level. Youth is not that interested in digging into what could be interesting emotional quandaries that it presents throughout the volume. The writing is like a stone that skips across the surface of the water – glancing, limited, and then moving on to the next point of contact. Youth asks questions like, “What happens when an upset and angry teenage Superman takes his rage out on bullies at the local club?” That question has an obvious answer, and this comic asks a lot of obvious questions like it, making the plot progression predictable, and, thus, a little dull. Of course, there’s that nominally scary military operation after the teens that does more dying than killing, but the book isn’t actually about answering these questions, either. All of the plot, as it stands, is there to accentuate the emotional landscape of teenage lovers who are suddenly thrust into a world they don’t necessarily understand or have the tools to handle.

That emotional landscape is worth exploring, and, to their credit, Pieres and Diotto do try to explore it, but the meat that they put around the proverbial bone is so surface-level that it hardly makes Youth something new, let alone something that “redefines the teenage superhero story.” Add this lackluster performance and the workman-like art to an ending that is both gruesome and guileless, and what you have in Youth is a book that promises far more than it can actually deliver.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply