I re-read the original version of The Eternaut when the Coronavirus started to hit my country. Published between 1957 to 1959, Héctor Oesterheld and Francisco López’s alien invasion tale felt oddly appropriate, particularly in its description of a world in which every venture outside the household becomes a brush with death. The masks we have to wear today are not as elaborate as the full bodysuits worn by the protagonists of The Eternaut, but symbolically they feel similar. What struck me in that re-read was how hopeful the book was. Not in terms of plotting, at every turn things seem to be getting worse as the invaders deploy more sophisticated and terrible weapons, but in its conception of humanity.

The survivors of the first deadly attack quickly come together, join forces, and fight back. Unlike the more common post-apocalyptic scenarios, such as The Walking Dead or Mad Max, which center on a single protagonist, The Eternaut is a tale of the group. It’s about humanity transcending its baser instincts. It felt good, reading it at the time, maybe we could be like that. Maybe all the horrible things happening can bring us together?

Eight months later, I sat and read The Eternaut 1969, a “remake” of the original, which was published ten years later. Meanwhile, in our world, humanity didn’t come together. Iin the face of adversity, many chose to do what is comfortable over what is necessary. Even the simple act of putting on a mask, designed to save others, became a political hot point; because it makes the individual slightly uncomfortable, many chose to risk others, making excuses all the way to mass death. All the while various governments worry more about abstract notions of “economy” rather than tangible human lives – throwing body after the body into the jaws of Moloch, hoping to ignite the wheels of commerce.

The Eternaut 1969 feels as appropriate now as its predecessor was. Oesterheld remained the writer, but Francisco López had been replaced on art duties by Alberto Breccia (The Eternaut 1969 is published as part of Breccia Library, which hopes to bring all his major works into the English speaking world). Both tales begin alike, with a deadly snow falling on the city and killing all it touches. Both share the same main cast, a group of friends who happen to be playing cards together as the crisis begins. Both have many of the same plot points, the group ends up conscripted into military service and fighting against new waves of alien threats.

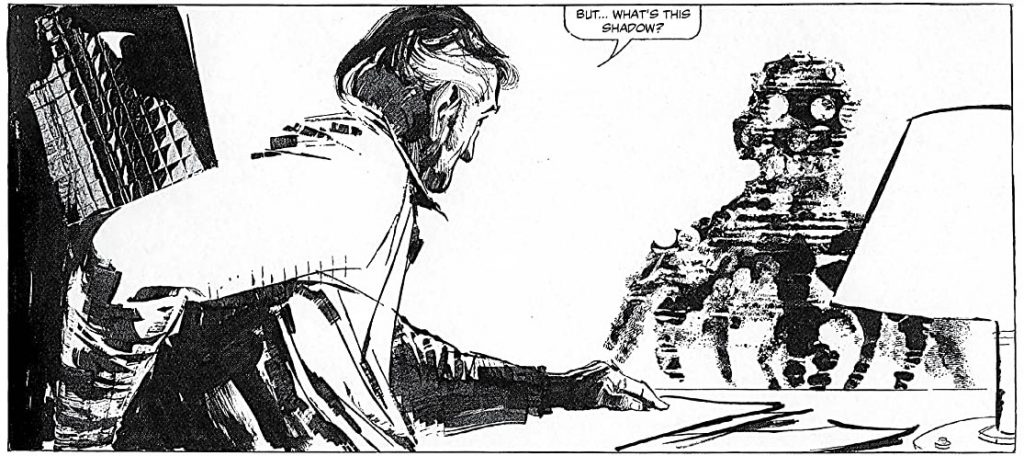

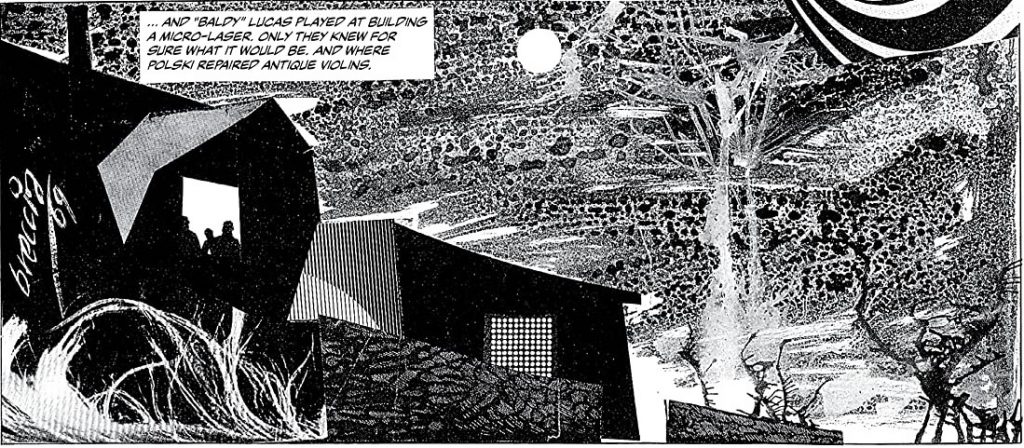

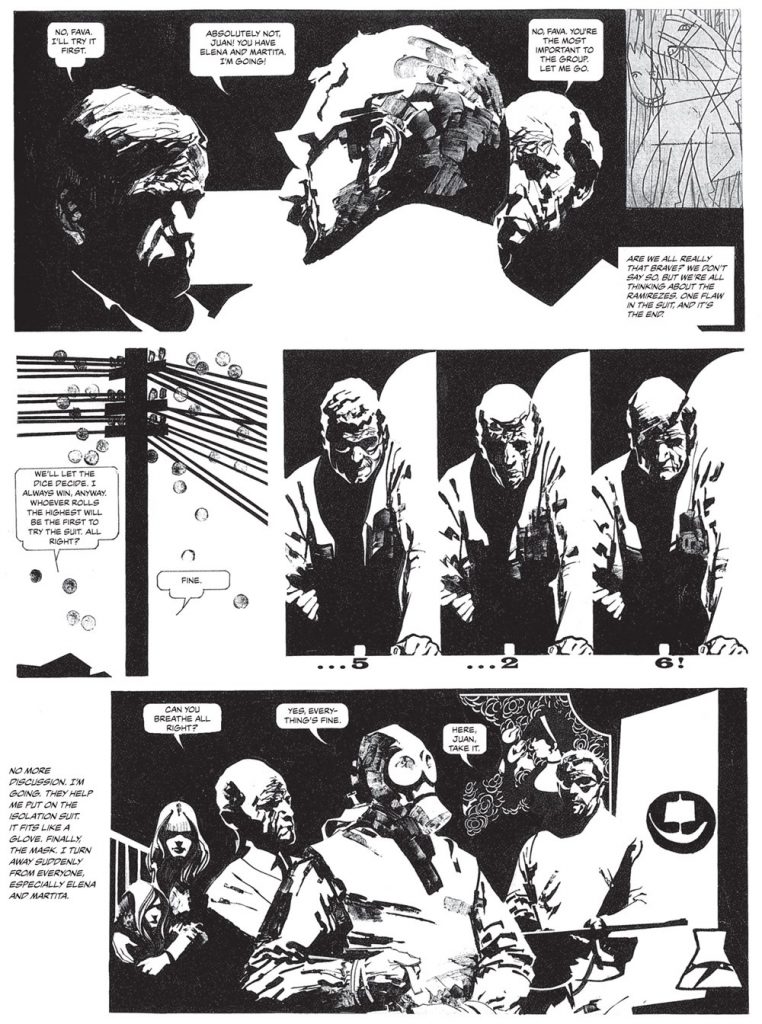

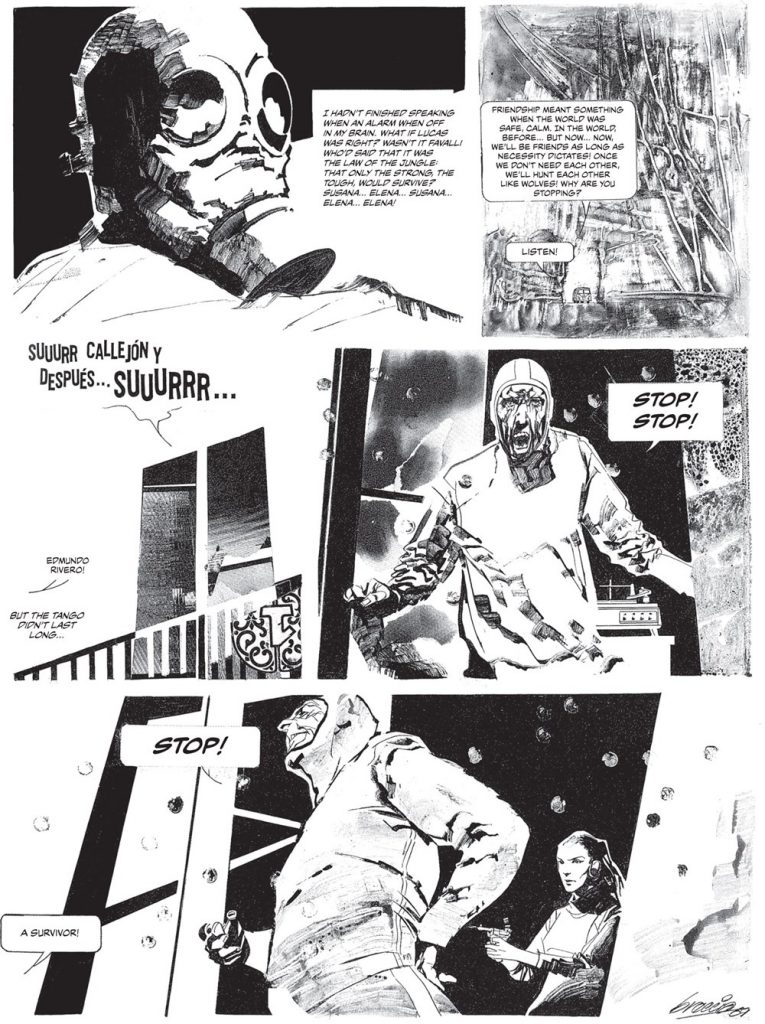

Yet the two works are night and day. The first thing one notices is Breccia’s art: López’s take on the world of The Eternaut was that of steadfast naturalism. Much praise has been heaped on his attention to details in depicting the ruined Buenos Aires, representing actual buildings in various stages of destruction and keeping true to geography as the characters move around. Breccia, on the other hand, pushes naturalism aside; his backgrounds are often splashes of dots and lines, walking outside the house the characters appear as if stuck in a mire. Likewise, his depictions of alien monsters favor shadow and amorphous forms, never settling on clear-cut models. López tried to show things exactly as they were in the script, to give as clear a view of the events as possible. Breccia attempts to show us how living like this would feel, to put us in the terror-stricken mind of these characters to whom the world is now strange as what the reader sees.

This sometimes brings the story close to full-on abstraction. On page 32, a straightforward scene in which the alien Beetles attack the humans with their “light-throwing” weapon is shown with splashes of black and white, lifting a soldier in the air, his face frozen in fear. A page later, Breccia depicts a scene of a tank exploding by breaking down all forms to the barest number of lines and letting the white overwhelm the page. Breccia seems to think that the original story, already well known enough, gives him a chance to experiment with his presentation — even if it sometimes means a lack of clarity, it matters little because the readers already know the plot (for that reason, it is preferable to be at least acquainted with the previous telling to better appreciate where this take deviates).

In the same manner, the story gets a new, sinister edge to it. Early on, an ominous radio broadcast announces that the “great powers” (USA, USSR) sold out South America to the invading aliens in favor of getting their own piece of the planet when the conquest is through. In the original version, the fate of the other countries remains mostly unknown, but the protagonists seem to believe they are struggling as well. In The Eternaut 1969, when the heroes are drafted into military service they are not asked nicely. They are threatened with death – pressed for service like criminals. Juan Salvo, our point of view character, is utterly cynical about his new position, figuring his group is nothing more than cannon fodder.

Breccia’s dreadful imagery, conjuring the stuff of nightmares, makes a proper fit for this version, just as López’s assured draftsmanship fitted the original. As noted in the background material, Oesterheld was a different person from the one who wrote the original. The Eternaut 1969 is far more forceful in its didacticism and political opinions – not alluding through plot and character but directly addressing readers through captions: “The world powers always has us bound at their feet. Before, the invader was the countries exploiting us, the international corporations.”

Sadly, the political radicalism and the overtly-experimental nature of the art made the work unpalatable to the general audience. The Eternaut 1969 is barely a quarter the size of its predecessor, forced to an early finish by the publisher. The last few pages of this collection are just a mad dash trying to fit in over 150 pages of the original story – it is an endless montage in which words often overwhelm the action on the page, with one large caption box following another. It’s not so much a “story” anymore, instead, it becomes a jumbled summation. It is like the final pages of Kirby’s lamented OMAC, in which the series hurries into an apocalyptic finale just to give everything that occurred prior a sense of a proper ending, where none can be found.

One cannot recommend The Eternaut 1969 just for its own sake, as a story. Gaining satisfaction from following the events and growing attached to the characters, sketched so briefly before the pacing overwhelms them, is nearly impossible. However, judging it on these terms feels limiting, as limiting as the editors who canceled it early-on due to public pressure. To look at something like this and to rate it on something as simple as “plot” and “character” is to miss the forest for the trees. Oesterheld and Breccia captured something here. The sense of a world in which all the comforting lies the middle-class base their existence on are laid bare; the structure is rotten and now we get to notice it for the first time. If The Eternaut 1969 appears like a nightmare, with all the inconsistencies and illogical elements of one, what could one say of the real world right now? Are we, sent out to work knowing death is so close, so different from Juan Slavo and his friends? Are we cannon fodder sent by foolish leaders who know only to sacrifice the little people, victims of higher powers desperate to preserve their place in the hegemonic ladder in the face of a massive crisis? As abrupt and confusing as it is, The Eternaut 1969 feels less like it belongs to the last century and more like the timeliest thing on the shelves. A work whose rage and urgency echo through time like its main character. In the story, the Eternaut travels from the future to warn the people of the dangers that are about to unfold. Likewise, The Eternaut 1969 delivers a time-traveling warning — we should heed its call.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply