Too often we think of ‘horror’ as a genre. A list of superficial accouterments that turn the usual into the unusual. Vampires, ghosts, masked killers… the works. Yet, through the process of repetitive use, we often allow the unusual to become commonplace, naturalized. Even the dreaded ancient gods from the cosmic horror stories of Lovecraft have been made familiar. Here is yet another story with trans-dimensional, many-limbed, octopus deity – “It will swallow our reality whole!” or something. You’ve heard it all before and you’ll hear it again.

Enter Pocket Chillers, an ongoing series of one-shot terror tales that are unified by the mood they attempt to evoke. So far the creators include writer-artist Douglas Noble and artist Sean Azzopardi. This isn’t the same old song-and-dance. This is the genuine stuff: as in genuinely weird, genuinely disturbing, genuinely scary. It would be tempting to write that this type of stuff “transcends the genre” or that it’s “elevated horror,” but it is neither. This is simply horror done right, horror as mood, a sensation of dread at the back of your head.

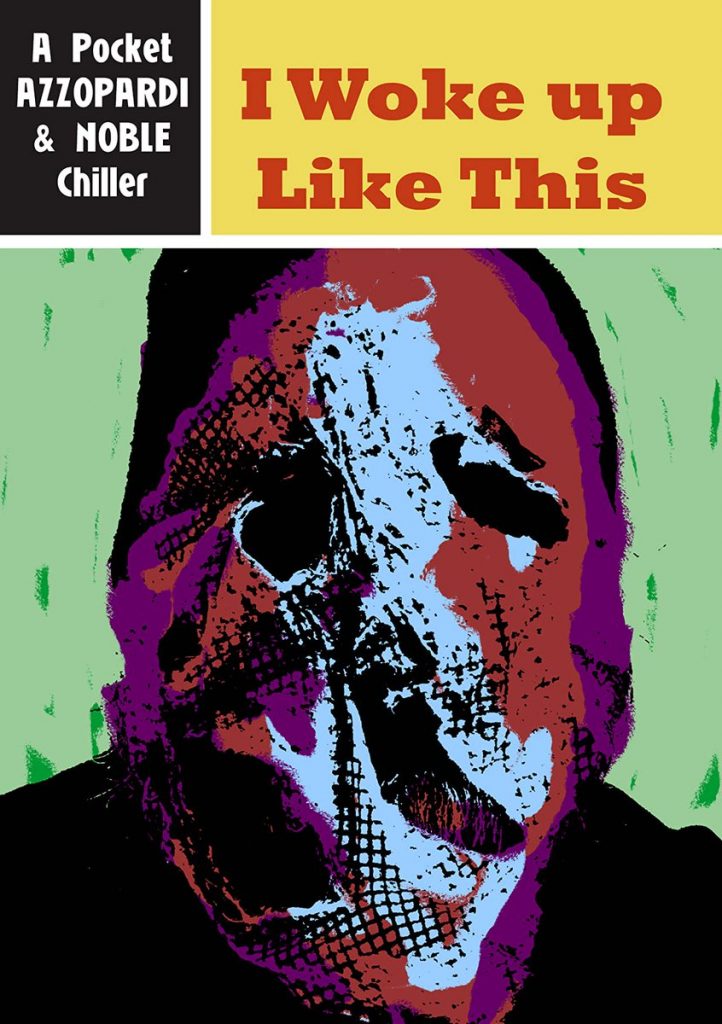

The first in the series, “I Woke Up Like This,” tantalizes the reader right from the cover: A face hidden behind a mask (we can’t quite make the material), the eyes are two black holes that seem to go one forever. It’s all in the color choices, the contrast between the sickly green background and the different hues across the mask; as if it’s being hit by a dozen different light sources (at least one of which is The Color Out of Space). Before you even open it, the issue already feels like a gate into another world.

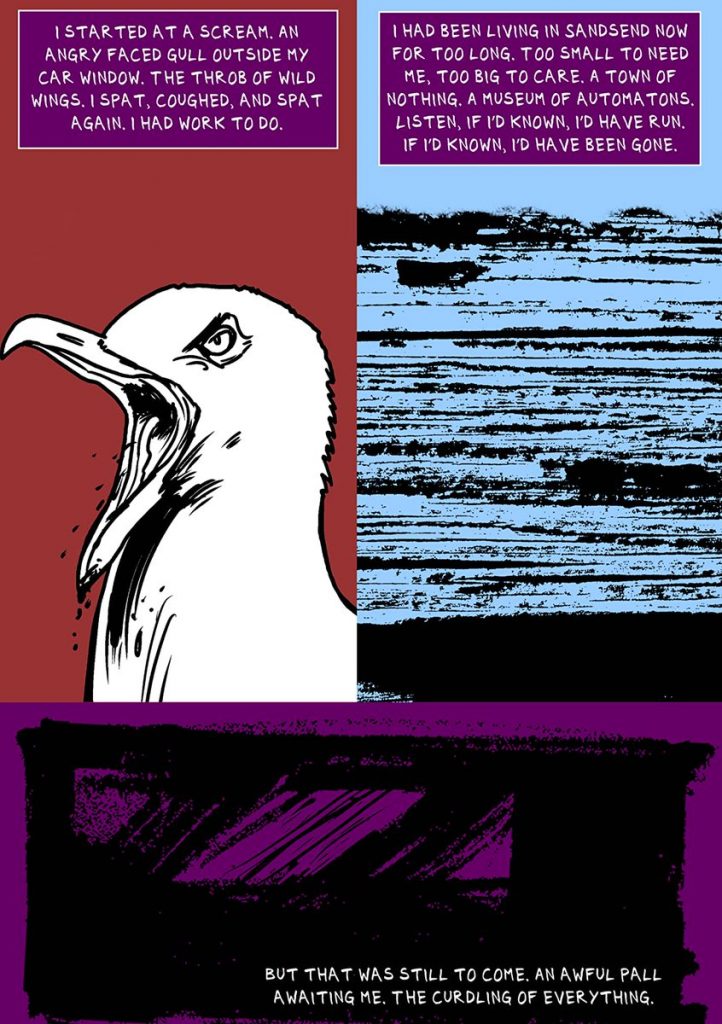

Inside, we follow the tale of one private detective who, like the reader, wakes up to a world that isn’t quite right. From there we take a step back to see how we got here. These are all classic ingredients, a private eye, an angry father, a girl who needs watching, we think we know what’s going to happen. We expect things will get weird, but we can’t quite expect the “how?” Azzopardi’s pencils gracefully shift between the low-key realism of a bird in flight and an impressionistic gesturing that depicts a cityscape basseted by ugly industrialism. Either way, the sense is of the sort of normality that hunts us on a particularly grey day and the building sense of dread. What is it the detective has seen through the window? Never clear, the lines are like scratches in reality. The blacks slowly sculpture their way through the strong background choices (red, purple, blue).

It’s just a long, piercing, wail of a comic. Like listening to a Drone album building-up steam towards a final scream, a scream that will never end: “This is beyond your logic, detective. There are no clues for you. There can be no answers. The sky is cracking.” Is it a story about environmental doom, about the “dark Satanic Mills” that William Blake warned us about? Is it a story about mental deterioration, the realization that one walks simply towards inevitable death? Is it just about living in the UK? Yes. All of that and more. This is a comic that you can hear and feel; there’s something tactile about it, even though the computer screen.

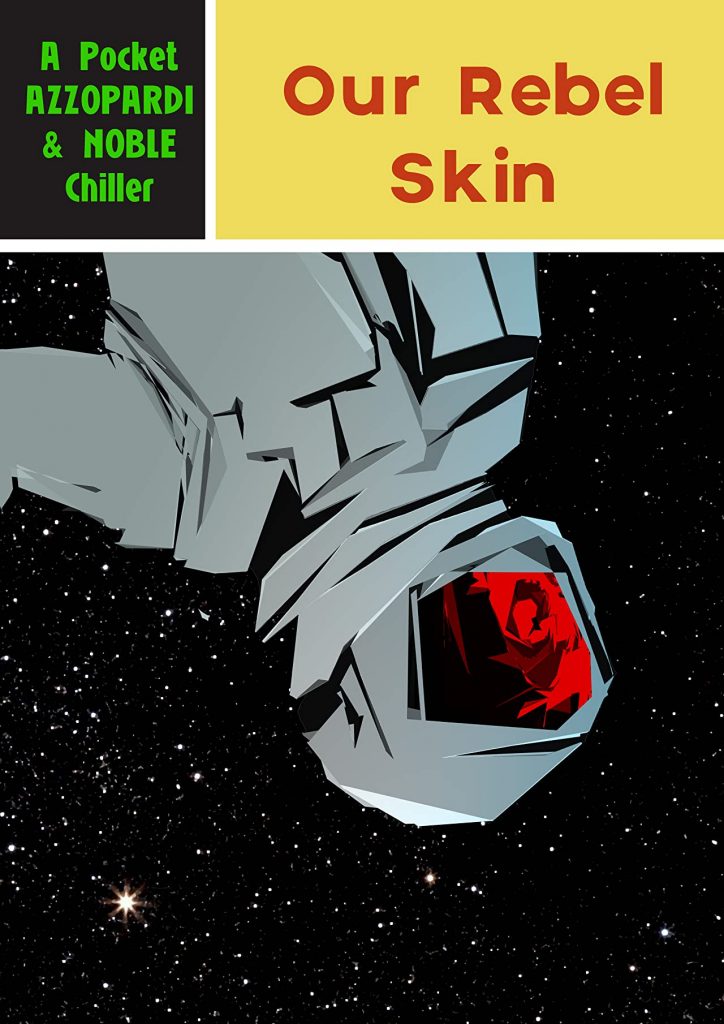

Compare this to the third issue, “Our Rebel Skin,” a science fiction tale about a lonely astronaut. Told not necessarily in order, and in a series of one-shot images that constantly hint at a larger narrative without elaborating beyond the limits of the page. Once again there’s a creeping sense of dread, but this one is played differently, more like a Shakey Kane comic. Kane’s works have that unique sense to them, colorful and popping, but always in a manner that makes you believe things are rotting beneath the varnish of old toys.

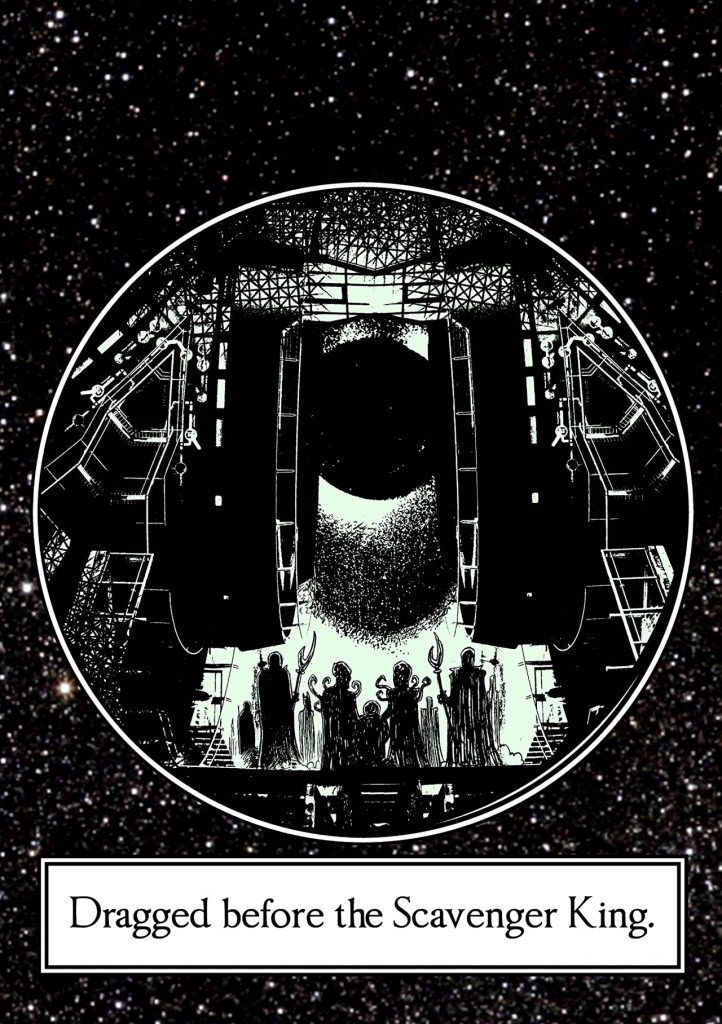

“Our Rebel Skin” plays a similar game. Taking something familiar — old science fiction clichés — and burrowing into the core of it until it finds that which has been trying to hide. The unpleasantness gnawing at our souls. We know it is there, but we don’t want to know. Through the one panel per page model of “Our Rebel Skin,” we witness a world deteriorating in super-speed, played on all levels at once: the personal (the astronaut, skin rotting out from illness) to the societal (the lower classes, bred as food) to the cosmological (the Scavenger King and his struggle for dominance). These two issues are utterly different in terms of plot and presentation. However, when read together, it makes total sense to find them under the same umbrella.

The second issue, “Gash Meat,” is both written and drawn by Noble. In many ways, its plot is even more abstract than the other two. What’s important is not what is happening but the feel of them. The pages switch backgrounds, from blue to purple, again helping the black within the panels just pop out at you. This is a world of shadows; not the elaborate and stylized shadows of noir fiction, but the kind that swallows everything. A shadow of creation itself.

You read that story, quickly getting its beats (and the panels do give the impression of poetry in their flow). The story drags you slowly into its world, the reader knowing just what happens within the panel borders and nothing more: the cracked TV that seems to sputter between static, symbolism, and truth; the couple who seem so crazy in love, so young and passionate, it’s possible that readers don’t fully notice what they did (and what they plan to do next); the person on the floor, rising up, slowly, his face covered with scars and a liquid that could be blood. He gets closer. The door opens. You know what happens next. Or, at least, you think you do.

Pocket Chillers never quite gives us the answers we crave but leaves us with questions that we should ponder instead. In everything having to do with look and design, it is a superb work, one fully committed to the ideas it wishes to embolden. We need more comics like this. Comics that is like dark matter. We can’t quite explain fully, but we know it has to be there.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply