Tom Murphy and Jane Gibbens Murphy’s South London based Colossive Press has expanded on their interest in the hyper-local and esoteric with their Colossive Cartographies project. Each contribution is super specific and singular, as you’d expect, but each one also pushes towards universality, helped in part due to each installment leaning towards the abstract. These are maps, they just happen to not show you the way.

Colossive has been putting out multimedia publications for a while now, and it’s clear that the Press is a labor of love. The Cartographies series came about thanks to the pair learning the Turkish Map Fold technique in a bookbinding workshop. This, the subsequent series, which so far boasts eighteen installments, is meant to act a little like a 7” singles club but in a format similar to European comics anthology mini kuš!. The “instant collectibility” aspect could result in a sort of disposability in the long term, but there’s enough love and attention in these that they’ll retain emotional and artistic value beyond the zeitgeist.

The University of Utah’s Book Arts Programme helpfully defines the Turkish Map Fold as “a unique and sculptural book form made from a single piece of paper, with an optional cover. As you open the book, the piece of paper unfolds entirely so you can see the entire sheet.” Contradicting my immediate guess, the internet helpfully informs me that the “Map” in Turkish Map Fold has nothing to do with representations of an area. Instead, it’s a reference to the mathematical-artistic practice of paper folding which, noting the creases and the folds, envisions the materiality of the folded paper itself as a landscape.

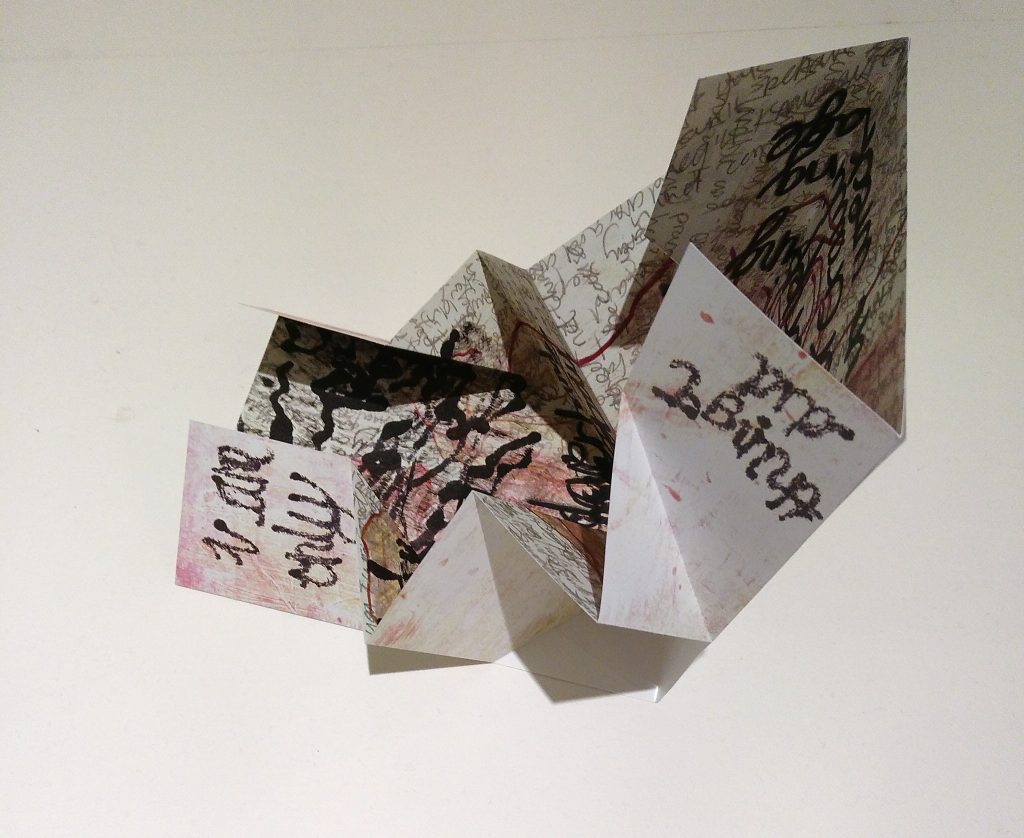

The cartographic element of Colossive Cartographies doesn’t have to be taken literally, then; and indeed, cartography is a term that has been utilized by researchers outside of geography departments as a way to describe the tracing of both internal (emotional) and external (cultural) phenomena. Of the Cartographies included in the Series Two batch (which includes issues seven to twelve), iestyn’s (stylized sans capitalization) Lining up the cutlery ready for the dishwasher is a good representation of subjective cartography, using this as an opportunity to do some (sub)conscious digging. This fold-out is dominated by scratchy handwriting in pencil, spilt ink, half-comprehensible black pen text, and hands, drawn in red crayon, stretching upwards.

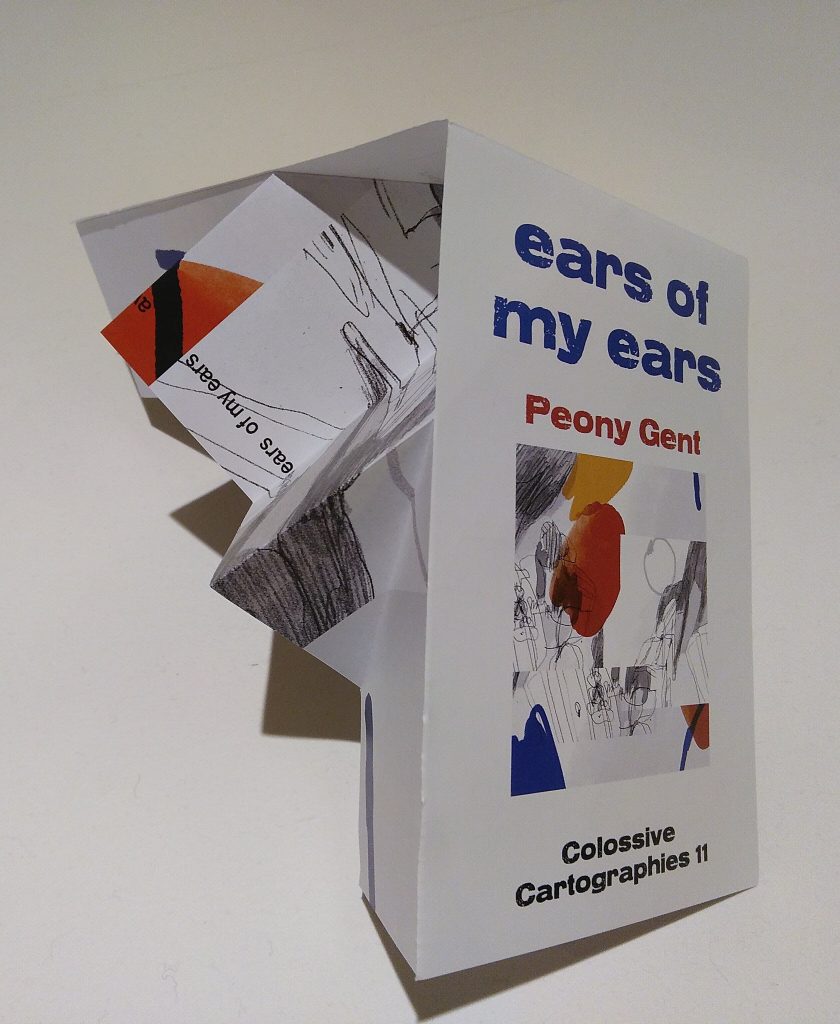

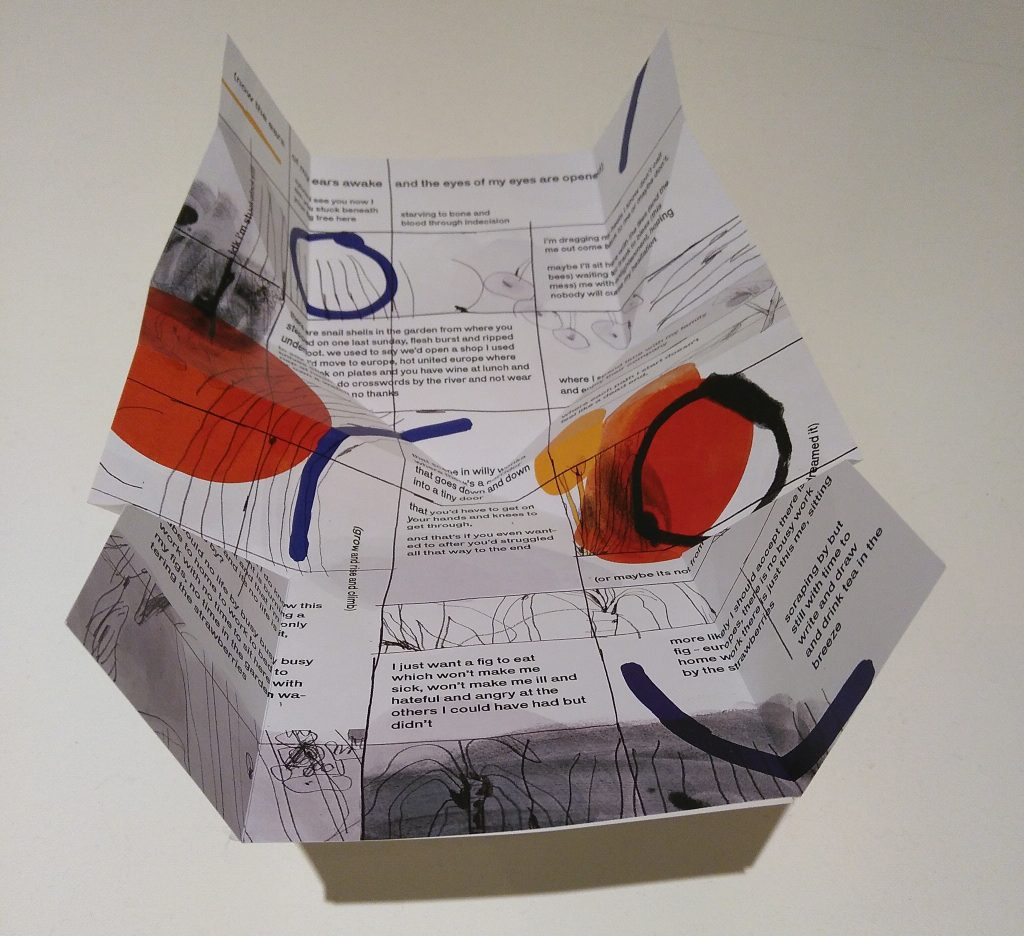

Peony Gent’s ears of my ears makes good use of a loose take on the De Stijl school. Here, Mondriaan’s uneven check pattern is appropriated to create frames that enclose sketches, splashes of color, and text. The verbal element of this map sits somewhere in between prose and poetry, and Gent also makes nice use of the back of the page to suggest “the other side” of the front’s ruminations on the quotidian.

Elsewhere, Colossive’s own Tom Murphy provides a visual/graphic adaptation of Paul Verlaine’s poem An Exchange of Feelings and creates an impressionistic tone through an eight-panel page. Henry and Stanley Miller’s Dream Buffet is a psychogeographical map of what the pair consider to be the perfect breakfast offering. It’s a surprising dose of fun and pastel colors in an otherwise quite serious collection; the inclusion of a picture of squelchy baked beans on the backside is an entertaining detail.

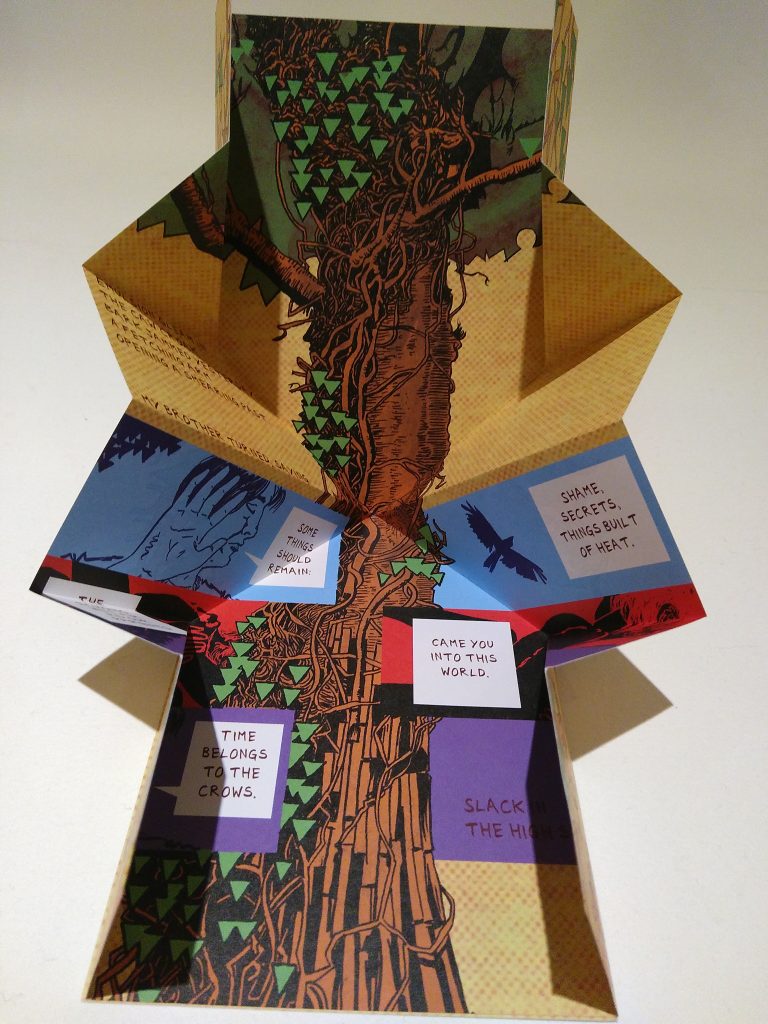

I came across Cartographies thanks to Douglas Noble, whose own An Unfolded Photograph is also here. Based on the little of his I’ve read, I’m a big fan of Noble; he’s preoccupied with human relationships with place and nature, and also with the pagan. All three elements are here, wrapped around the tree that rises through the center of the page in a strangely geometric style. He also provides a small amount of his pitch-perfect words (Noble’s rhythm and precise vocabulary is often fantastic).

Finally, Caves of Ahuna Mons by Gareth A Hopkins depicts the luminous caverns that exist on the dwarf planet Ceres. Demonstrating a van Goghian interest in painted lines, the six panels on his page attempt to entrap an explosion of thick, deep colors. There’s a real sense of moment on this map.

Colossive doesn’t limit themselves to describing their enterprise as one solely interested in comics, and their Cartographies series sits at the borderlands between comics and zine culture more generally. Taking iestyn’s contribution: it seems not really like comics per se — more like a picture poem, or word art — but the way the text on the back of the page is seen and read as the work is unfolded, and how that text reads differently depending on how you have the paper opened (or partially closed) is certainly an experiment with space, of spatial relations, the type of relationship that comics knows and exploits more than any other medium.

The more comics-y contributions aren’t necessarily the best exploitation of the physical landscape the Turkish Map Fold’s format offers. Gent’s and iestyn’s contributions, for example, both make full use of the two sides of the paper, and their contents also play well with the sense of discovery and revelation that the act of folding and unfolding the paper engenders.

At their best (or at least most interesting), the Cartographies stretch comics’ interest in space to depict and encourage what Walter Benjamin described as “distracted perception” – something comics scholars have claimed 2D comics have been exploring for some time. Benjamin, preempting the Situationists, was concerned with the way in which contemporary urban life was becoming overwhelmed by signs. At the beginning of the 20th century, images and words began to take up social and private spaces. His idea was that the only literature that would suit such a world is a literature uninterested in traditional forms, such as prose and poetry, and one that would instead embrace the multimodal and multimedia, one that would juxtapose and synthesize visual and verbal and tactile methods of communication (it’s arguable that social media got there before major publishing houses started even trying).

When Colossive’s Cartographies encourage the reader to navigate, in nonlinear ways, the (literally) multifaceted paper and its content, one gets a sense of the sort of depiction of the contemporary world that Benjamin was imagining.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply