Whether on two legs and in full contemporary clothing or on all fours and simply imbued with a higher sentience, animal-people allegories have existed since time immemorial. These stories oftentimes serve to impart parables and cautionary tales. Aesop’s tortoise and hare taught us about moderation and haste. Anansi the spider taught us resourcefulness and resilience. The Trickster Coyote, ubiquitous across many southwestern Native American cultures, taught us about the duality of wisdom and foolishness. And in Disney’s Zootopia (2016), Nick the fox and Judy the rabbit taught us that in a distant past people of color preyed upon white people.

Wait . . . what?

Suffice to say, animal anthropomorphism can encompass a vast range of human experiences, but there are also points where the lines get, shall we say, fuzzy when grappling with human-engineered social issues of racism, prejudice, and oppression. Notable examples in comics include Maus (Spiegelman, 1980-1991), Blacksad: Arctic Nation (Canales & Guarnido, 2003), and Beastars (Itagaki, 2016-). These are stories that directly address oppression in some form or another — Maus hones in on the Holocaust, Blacksad: Arctic Nation on 1950s racism in the US. However, each takes a unique approach, from heavy-handed coding to a more graceful allegory, that shapes its art and story. It’s through these works that we see which are successful in interpreting a very human circumstance and which demonstrate effort but miss the mark.

Let’s unpack some academic terms first, namely “coding.” Coding crops up in our daily lives, from comics to press conferences. For instance, we all know that Minnie Mouse is coded as female purely by her design: chunky heels, extra-long eyelashes, and that whopping, red bow on her head. The understanding is implicit. Similarly, when we hear a politician refer to “inner-city youth,” we know he means Black and Brown children; or when we hear corporate boards talk about “diverse candidates,” as if it were uncomfortable to simply say “people of color” or “non-white candidates.” In certain animated films produced by conglomerate American studios, this can look like saying “prey and predator” to refer to white people and people of color, respectively. Coding is a neutral, academic term to describe how one’s brain fills in the gaps to understand a situation based on schemas the brain holds. Schemas are the short-hand connections our brains are socialized to make, typically based on experience or what has been reinforced through the messaging around us.

Through coding, storytellers save time and space building context by allowing the audience’s own schemas to fill in the blanks. When not enough care is given to the story’s context, coding then comes off as sloppy and heavy-handed.

Ergo, Zootopia.

“You can’t just touch a sheep’s wool,” Judy Hopps hisses at Nick Wilde in the film as he does just that. This interaction is coded and we as the human, primarily American audience understand exactly what the implication is. The sheep’s pronounced coif of wool that Nick fluffs and describes as “like cotton candy” is a stand-in for a Black person’s afro. One hopes that in the twenty-first century most non-Black people understand the microaggression of touching specifically a Black person’s hair. In short, it’s a long and painful history of white entitlement to Black bodies. However, Judy’s admonition is delivered without context. Judy could have said, “That’s rude,” letting the audience know it is a general violation, but she specifies it’s a sheep’s wool that shouldn’t be touched. What happened to sheep that touching their wool, in particular, is bad? Is there an unspoken history of sheep enslavement or coercion for their wool? This is never explored.

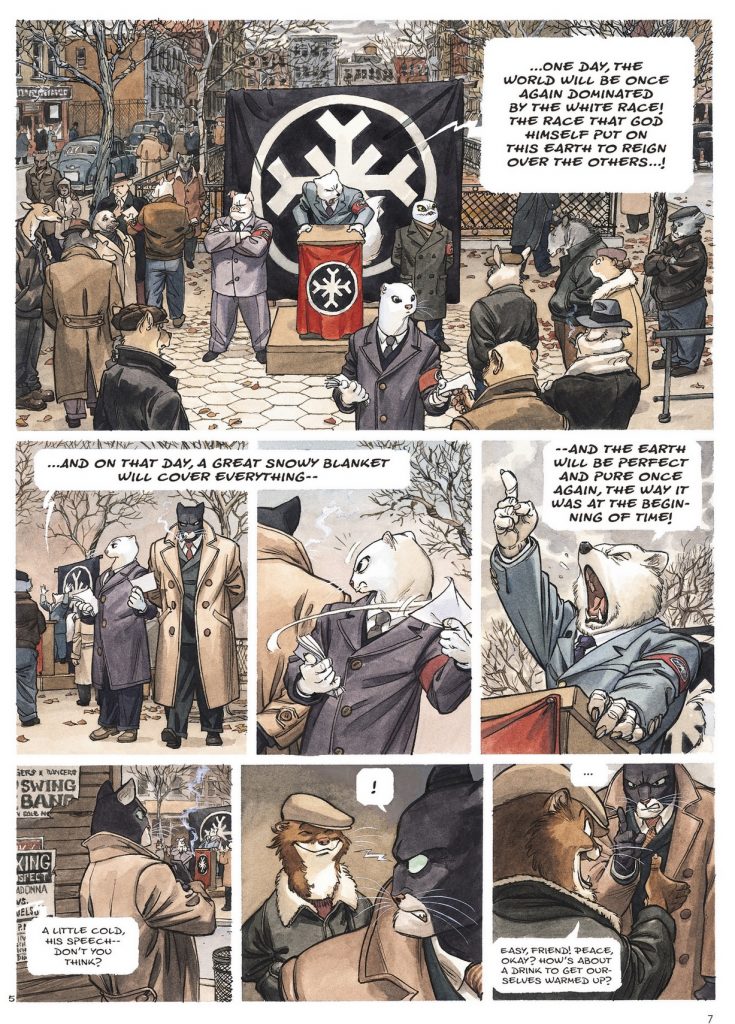

Similarly, in Blacksad: Arctic Nation, there is a crumbling lack of context for a story that is set in a depressed, 1950s American suburb. This installment of the titular feline illustrates a clear divide between black- and white-furred animals. The story opens with a lynched black condor followed two pages later by an arctic fox — notably, in his winter coat — concluding a public tirade with “the world will once again be dominated by the white race.” The fox wears a red armband with a snowflake encircled on a black field. This emblem appears on the fox’s podium and on a banner behind him. If there ever were an example of heavy-handed coding this is it.

The audience is also presented with racism in the most direct, albeit superficial, depiction possible: white versus black. White-furred animals hold positions of local and systemic power. The police chief, Karup, is a polar bear who displays a Confederate flag and the saber of Robert E. Lee in his office. The audience is left to assume this must follow the same timeline as US history, simply with an anthropomorphized population. However, we’re also given a scene at a convenience store wherein black-furred animals arrive to strongarm Blacksad and his sidekick, a news reporter. They take issue especially with the white fur in Blacksad’s muzzle, attempting to paint it black. Essentially, the scene advances an incorrect notion that “both sides are bad.” While it bears mentioning that Blacksad is written by a European team with an outsider’s view of the US, Blacksad’s attempt at capturing racism through anthropomorphic characters falls short because it doesn’t delve beyond the surface of, quite literally, black and white.

Art Spiegelman’s Maus, on the other hand, uses coding more intentionally to develop a relational metaphor. A retelling of his father’s account of the Holocaust, Spiegelman assigns animal species specific to characters’ nationalities/ethnic identities. Spiegelman’s father, Vladek, and other Jewish-identified characters are bipedal mice, which is a play on Nazi Germany’s propaganda depicting Jewish people as rats and vermin. Germans, in turn, are illustrated as cats; Americans are dogs; and Polish people are pigs, which, in Meta Maus (2011), Spiegelman explains was an attempt to find an animal with dually admirable and abhorrent pop culture connotations that would be abused for production.

And the metaphor remains just that — a metaphor. The coding strictly serves to cue in the reader on relationships among the different groups from one panel to the next. It never is employed as shorthand to explain the intricacies of the Holocaust itself. Moreover, the metaphor recognizes its limitations and adapts to what the narrative demands.

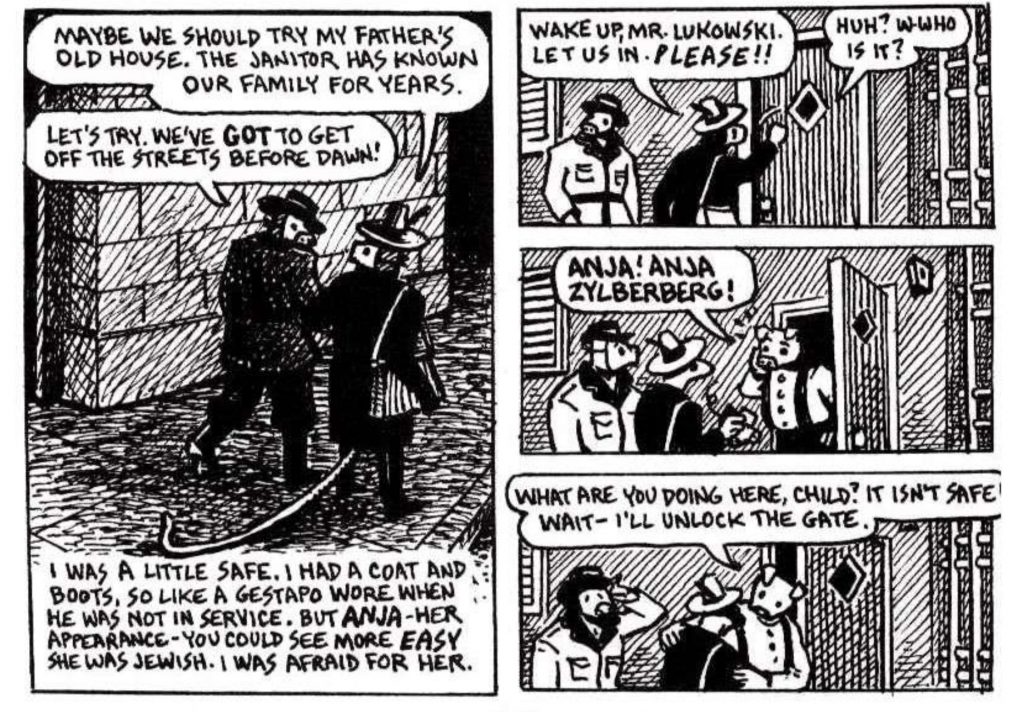

For instance, in Maus Volume I, chapter six, Spiegelman’s parents, Vladek and Anja, must covertly walk the streets of Nazi-occupied Sosnowiec, Poland at night. Vladek narrates, “I was a little safe. I had a coat and boots, so like a gestapo wore when he was not in service. But Anja — her appearance — you could see more easy she was Jewish.” While both Vladek and Anja are drawn wearing pig masks, signaling that they are passing for non-Jewish Poles, Anja drags a long mouse’s tail behind her. Never at any point in the rest of the comic are mice or any other animals drawn with tails. This is strictly in service to the metaphor to emphasize how difficult it was for Anja to hide her identity.

Spiegelman remains self-aware in the limitations of his animal metaphor. The art shifts again to accommodate a prisoner who claims to be German and is therefore depicted as a cat in one panel and as a mouse in a juxtaposed panel to capture his appearance to German officers. In Volume II, Spiegelman grapples with how he’ll portray his wife, Francoise, who is French and converted to Judaism. Since Spiegelman’s depiction of the French draws on their old stereotype as frogs, he toys with the notion of portraying her as a frog until their wedding when she would then transform into a mouse. Francoise vetoes this idea on the floor, so the graphic novel shows her only as a mouse.

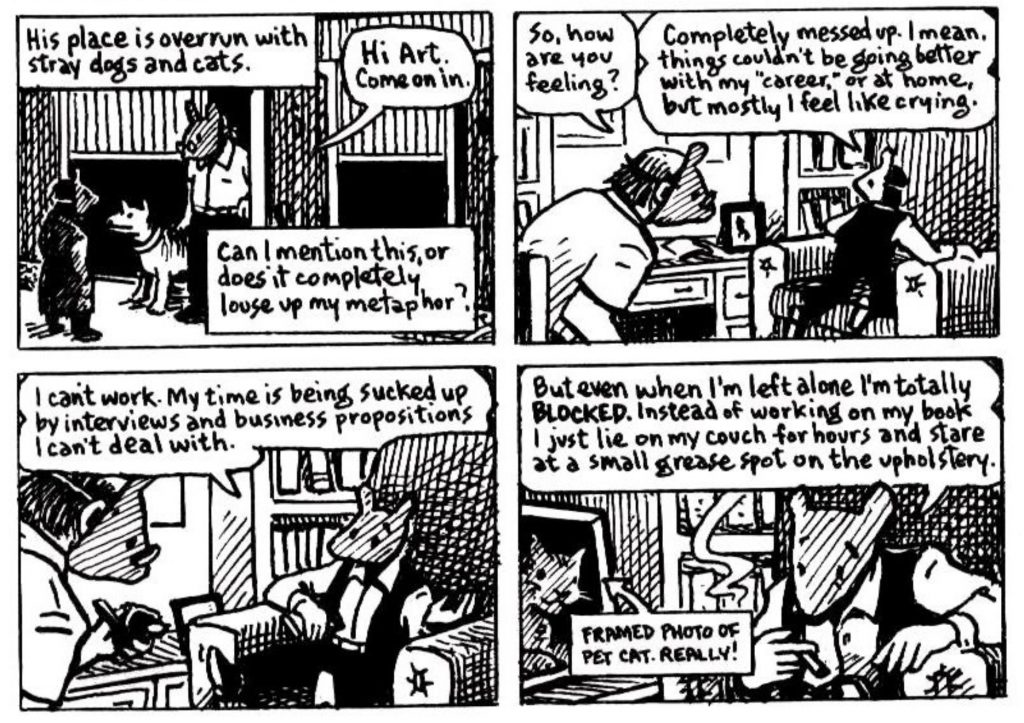

Non-anthropomorphized animals exist in Maus as well. The audience is shown “natural” dogs, most distinctly when searching for Vladek and his family, who are hiding in a bunker, and at the entrance to Auschwitz. In the opening of the chapter for its second volume, when Maus flips back to its memoir framing, Spiegelman mentions that his therapist has pet cats and dogs. He wonders in his captions, “Can I mention this or does this completely louse up my metaphor?” It’s also in this segment that he discusses the development of the graphic novel, and illustrates himself not as a mouse but as a human wearing a mouse mask. The coding, the reader is reminded, is strictly for the story. Maus acknowledges that its metaphor is imperfect and — when possible — breaks the mold to make room for elaboration.

But where Maus makes these adjustments gracefully, a work like Zootopia collapses under its strident premise of a distant past where predators consumed the flesh of prey animals. Although their society declares that all animals have evolved past these instincts, prey animals continue to express a mistrust of predators. This becomes more problematic when the film then codes predators for people of color in the US. Judy’s botched press conference is meant to be evocative of Hillary Clinton’s in 1996. A line in the movie goes as far as to state that predators are a minority, making up 10 percent of Zootopia’s population. While this might be true for a healthy biome, it’s absolutely incorrect to equate the natural occurrence of a minority population of predators with the minoritization (i.e. have been made into a minority) of nonwhite peoples in what we now call the United States.

Animal metaphors for human constructs of oppression, particularly racism, fall apart for the simple reason that race is not biological. Humans do not have naturally antagonistic relationships toward each other based on race the way animals do based on food chains. We know that race is a social construct, and not biological, in how its parameters are expanded or contracted in order to deny power to others. For instance, many Americans are familiar with the defunct, early twentieth century “one-drop rule,” or the notion that having one African American ancestor in one’s bloodline excludes them from being white. Conversely, blood quantums were enforced on Native Americans in order to erase their political presence. If a tribal association seeking federal recognition lacked enough membership with viable bloodlines, then no federal recognition or support need be extended. The effects of these systems of power that benefit one group to the disadvantage and outright oppression of others based on race create the very real impact of racism.

As a manmade construct with no scientific basis, racism then can only be successfully examined through a human lens, not an animal one. However, what if animals weren’t supposed to be either races or people at all? What would it look like if oppression were explored through an animal lens on animal-specific issues? This would present a very different storyline, but not one that isn’t relatable. Metaphorically, Maus, Blacksad, and Zootopia struggle because they attempt to play chess with mahjong tiles. Paru Itagaki’s Beastars manga, however, seeks nothing more than to play a round of checkers with the pieces required—and it excels.

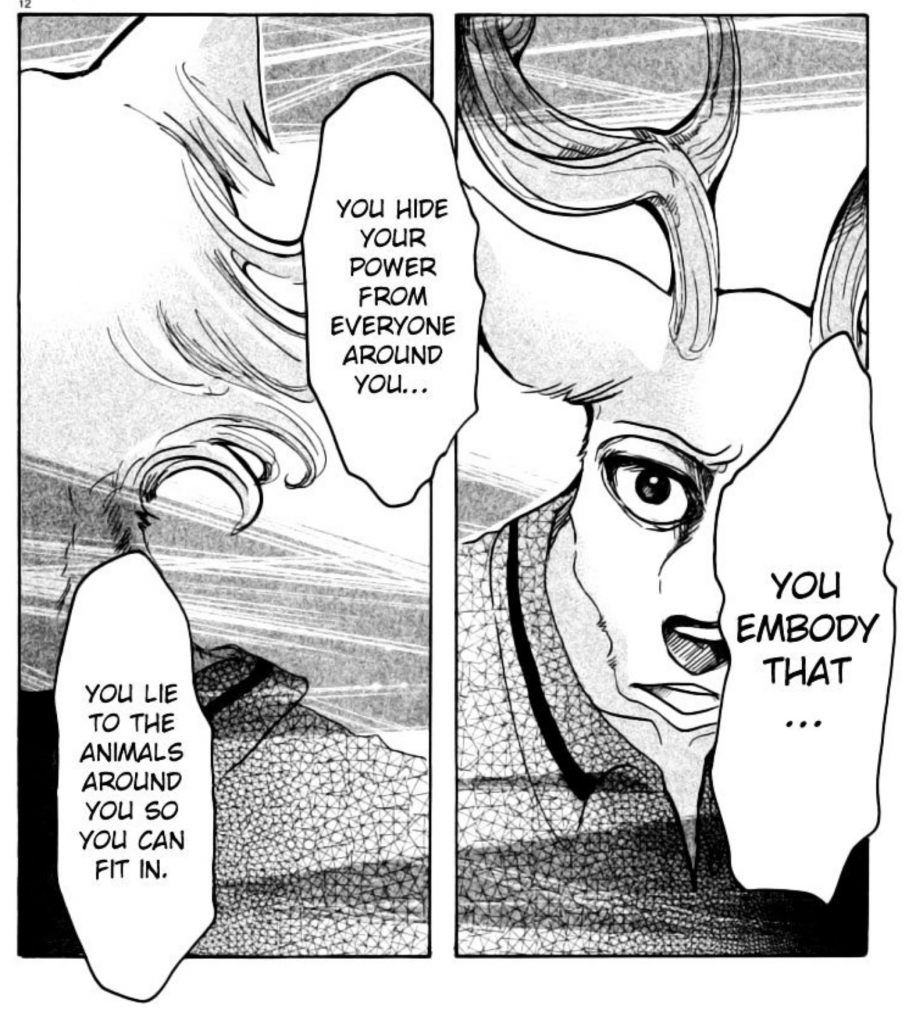

Set in a world of animal people, Beastars plunges into the clear unease between herbivore and carnivore denizens. When the students of Cherryton High find that one of their drama club friends has been shredded to bits by an unknown carnivore, everyone suspects the hulking gray wolf Legosi. There’s no pretense as to why carnivores shouldn’t be feared. Rather, characters like Legosi are illustrated with massive claws and unavoidably eye-catching fangs flashing from their mouths whenever they talk or smile. While the anthropomorphized society engages in human activities — going to school, working day jobs, attending civic meetings — everyone always maintains the outlook of their animal identity (e.g. expressing caution over carnivores, resisting urges to eat herbivores). Refreshingly, carnivores and herbivores aren’t coded for anything.

In a 2018 interview, Itagaki remarked, “I do sometimes consider that there might be humans who are going through the same problems that I portray with my animal characters, although some of the problems would be too disturbing if my characters were humans.” Essentially, the author acknowledges the themes of power and prejudice while recognizing that this is meant for an animal lens. Indeed, humans preying upon one another would be disturbing, but in the context of animals, it’s more acceptable. Beastars lets the viewer sit with the biological tension between the two groups and the overarching theme of power — who has it innately (carnivores), who has it socially (herbivores), and who subverts it. This is how Itagaki interrogates the crux of prejudice, unfounded assumptions, and the notion of instincts against individual free will.

In Beastars, herbivores exert a clear dominance over the day-to-day society. The city’s mayor, a lion, goes to the extent of having all his teeth removed in order to wear flattened dentures and adopt a more herbivore appearance. The reader also has the context for how this systemic oppression and marginalization of predators impact the daily lives of students at Cherryton. Law requires any predator over two meters to take strength suppressor pills and, after getting fed up with the deleterious side effects, a brown bear stops taking his medication — to disastrous results. In Beastars, we don’t focus on individual outliers, like a bad cop here or there, but on how whole groups are complicit in systems that benefit them. In this case, a society that is intentionally designed to marginalize carnivores. Carnivores can only have their instinctive craving met through a black-market district, which sells the meat of already-deceased or even raised-for-consumption herbivores. However, the audience is made aware that these societal restrictions do not entirely mitigate carnivores’ innate, predatory power.

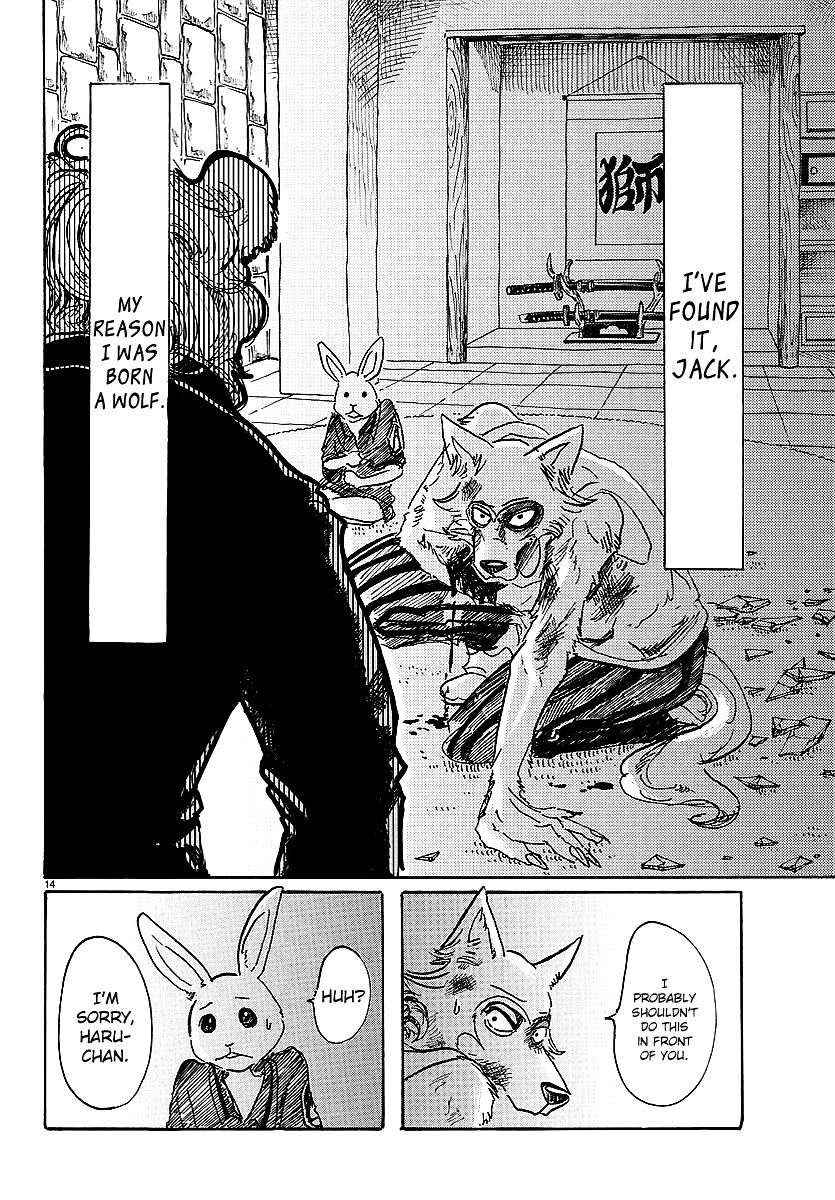

Legosi, the wolf protagonist, adopts a disarming and reserved appearance in an effort to avoid confrontation, wrestling with the self-loathing he has for the lethal claws and fangs he never asked for. The drama club’s star actor, a red deer named Louis, despises Legosi for both being inauthentic and having access to a physical power that he does not have. In chapter 41, Legosi finally recognizes his innate privilege as a predator and the ability to use this to protect smaller animals when he declares to his rabbit love-interest Haru, “My claws are for you, my fangs are for you.” Repeatedly, Beastars’ readers are invited to explore the overlaps in the characters’ identities and how they navigate the larger social constructs surrounding them. By building its story as a broader allegory to discuss power dynamics rather than stiffly coding animal groups for human ones, Beastars is able to have a more fluid conversation about oppression, albeit not racism. In fact, it never needs to broach racism — that’s a human concern.

Where does this leave us? Can our anthropomorphic narratives never capture the human construct of racism? The short answer: No — and maybe we’re the better for it. In How to be an Antiracist (2019), Dr. Ibram X. Kendi posits that no one is born racist, but we do perpetuate racist thoughts and, through behavior driven by these thoughts, racist policies. A person can go from being racist to being antiracist (and vice versa) depending on the thoughts they internalize and the actions they take. Neither state of antiracist or racist is a fixed state, like being a caiman or an okapi. A leopard might not be able to change its spots, but fortunately, we as people are capable of changing. In being capable of change, we are therefore capable of dismantling our own systems and constructs of oppression.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply