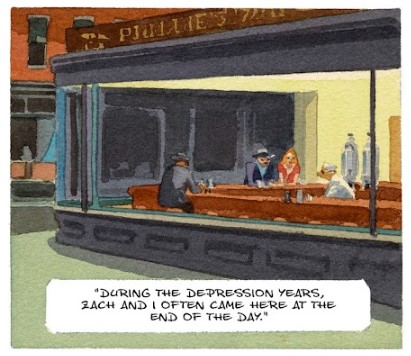

There’s a panel in the new Blacksad album that recreates Edward Hopper’s famous painting, Nighthawks. Considering the anthropomorphic animal world of Blacksad, you would probably expect something ironic, perhaps replacing one (or all) of the figures in the painting with actual hawks. But nope; instead, it is a loyal recreation of Hooper’s composition with some animal people. We are in the year 2022, it is weird to see something like this played in such a straightforward manner. Maybe in France – both writer and artist are Spanish but the series is published first in France via Dargua –, the painting is not as well-known source of evocation and parody, but I doubt it.

It is the single most obvious composition for a noir setting, a choice so self-evident to pick that it must be done in a sort of a knowing wink.[1] Unless we are talking about Blacksad. For Blacksad, here referring to both series and protagonist, is a wink-free zone. What’s more, it is a zone free of any nuance. Just like its animal characters, whose outwards nature always implies something about their inner lives,[2] it is exactly what it says on the cover. Of course, the dogs are cops, the lizards are cold-blooded criminals, and the feline Jon Blacksad is an independent being, observing corrupt society from a distance.

It is especially interesting to compare this surface-level treatment of the “animal noir” sub-genre with Blacksad’s less successful (at least in terms of public discourse in the English-speaking comics sphere) competitors. Both Bryan Talbot’s Grandville and Gabus & Reutimann’s District 14 began in a similar fashion, tales of crime and detection in a historical setting populated with animal-people, before revealing themselves to be more than a simple pastiche.[3]

In these stories, the funny animals are not just masks worn over the faces of regular people, a tool meant to enliven an otherwise rote murder mystery, but they are an inherent part of the world that effects the way the story progresses. A lizard in the hand of Talbot isn’t just a (often racially uncomfortable) metaphor for a cold-blooded person, but an actual lizard whose actions are partly dictated by its biological reality. This is not to say you can’t do it well in the other direction, both Barks’ Donald Duck and Sakai’s Usagi Yojimbo told extremely successful stories in which people are drawn like animals, but this is another example of Canales and Guarnido’s lack of curiosity.

Why pick a more obscure painting, a reference point that hasn’t been done a thousand times over, when you can go to the most familiar choice of them all? With Nighthawks, after all, no reader is at risk of being challenged – everybody gets the emotional resonance of that painting immediately. In case you had any doubt you are in a noir story before, you could be sure you are in one now.

The film noir genre, famously, began in the United States but got its cultural recognition in France, part of a general trend of the French appreciating and recognizing “junk” American culture as something deserving wider recognition. It also can be seen as part and parcel with the general European obsession with the idea of America that led it to cling to these mythical genres long after Americans had left them behind – especially in comics.

Consider the Western, possibly the Most American genre there is, and yet Westerns in American comics are few and far between for a good four decades now. Meanwhile, the genre still flourishes in Europe[4] – Lucky Luke is still as big of an icon as he was in the days when John Wayne was the biggest movie star in the world. Noir stories, likewise, are apparently more common on the continent than in America itself.

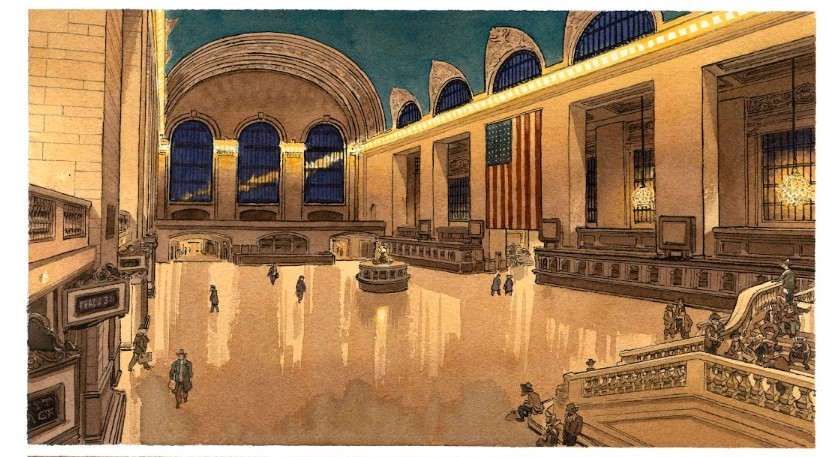

While noir stories can take place in every major metropolis, the French still appear preoccupied with America: Blacksad takes place in the United States, and its social background in that of America in the 1950s and 1960s – civil rights protests, Red Scare, the Beat Generation. In They All Fall Down, we are back to New York, the location of the first volume, and the subject is gentrification, brought to us in the form of the rather obvious Robert Moses analogue called Solomon[5] who threatens to destroy the unions that stand in his way to achieve immortality.

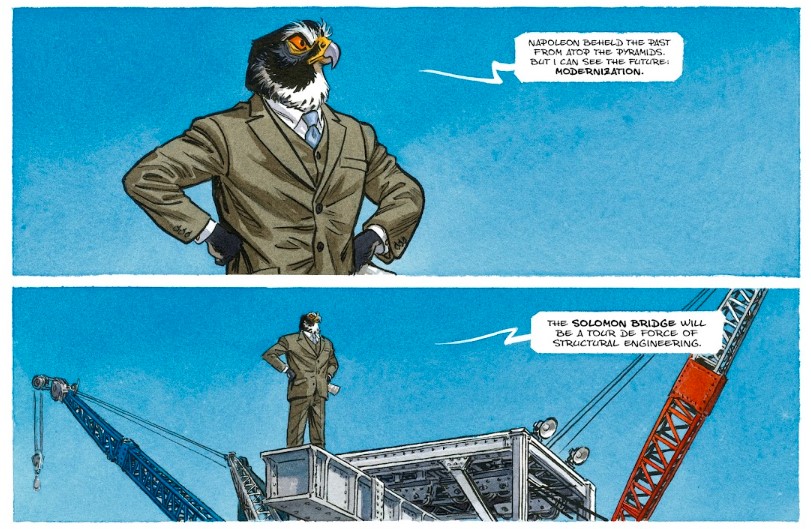

This is a worthwhile subject, such were all the major animating forces in previous volumes, but it is not treated with a worthy degree of seriousness. In Blacksad, all of the above-mentioned subjects – many of which are still open wounds in the psyche of the nation that affect people to this day[6]– feel like they avoid even the most cursory reading on the subject. Their main reference point appears to be other noir texts, a sign of a sign, allowing narrative shortcuts, the complex (sometimes overtly so) plots of original noir tales replaced with simplified versions. Blacksad evokes certain recognizable historical figures, from Adolf Hitler to Alan Ginsberg to Robert Moses, but, instead of creating verisimilitude, it creates a sort of generic soup of cultural references: Blacksad takes place in the “America” of “history” but fails to offer any specificity.

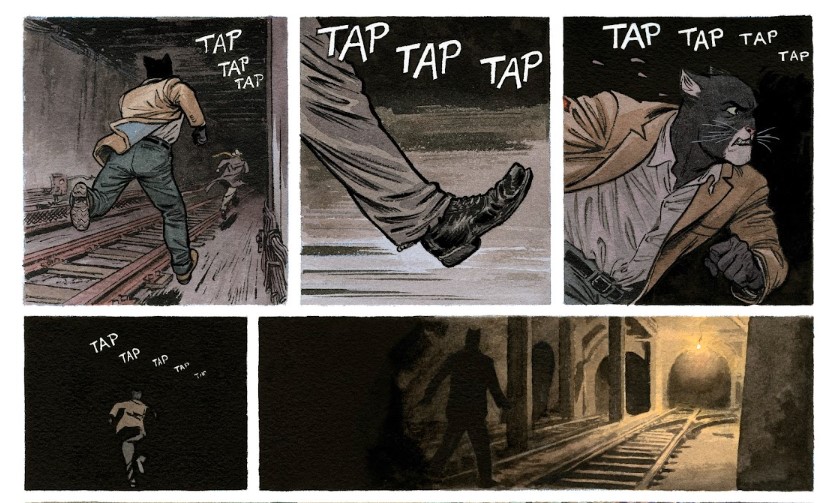

This, at least, is on the writing side. While the plot and characters work, the series often feels lacking in effort. One cannot deny that Guarnido is drawing the shit out of these pages. You may not like his style, the approaching too near photorealism with the texture of every hair or the sagging waddle on a turkey-person’s neck[7], but it takes a lot of effort. Not being an expert I won’t pretend to know if his New Orleans in Silent Hell or his New York in They All Fall Down is historically or architecturally accurate; but there is a proper sense of location in the art.

The scenes taking place in a construction site manage to properly display the size of the undertaking, as well as to explain (without using words) that what Solomon achieves is built upon the ruin of others – that in order for his beautiful buildings and bridges to rise, places that people already occupy must fall. He’s an eagle, looking at the city from above, and you can sense his uneasiness when standing on ground level and actually being forced to deal with people.[8]

It is a, sadly, familiar issue with much of the Franco-Belgium school in which the story feels like a coat hanger around which the lovely art could be draped – something that is utilitarian without offering any hint of ascendance. I think of the first Blacksad story, Somewhere Within the Shadows, about how excited I was when I read it the first time and how little of it retains.[9] And what does retain does so simply because it builds on things I already knew

Blacksad himself is modeled after the likes of Sam Spade and Philip Marlow; or, at least, our cultural memory of them. The long coat, the cynical approach, being good in a scrape, the constant philosophizing… but nothing in Blacksad feels “earned.” He’s all these things because that is what we expect of a private detective.[10] Hammett’s Continental Op wasn’t a familiar archetype when he made him. What’s more, he was borne out of Hammett’s own private experience with human folly, human ugliness, human pettiness. Despite the open-ended characterization, we don’t even know the Continental Op’s name, yet he feels so much more real than Blacksad.

Which is why it is weird that Blacksad is successful. In America, I mean. People count the time between each new volume[11], the books get showered with praises, and they seem to sell well. How? Not despite its faults but because of them. Because despite obviously wanting to be a Hammett or a Chandler, Blacksad actually feels closer in spirit to another noir great[12] – Micky Spillane.

It was Spillane, originally a failed comic book writer[13], who supposedly answered his critics: “These big shot writers could never dig the fact that there are more salted peanuts consumed than caviar.” His main selling character, private dick Mike Hammer, had all the accouterments of Sam Spade, but lacked any depth. Hammer, such a comic-book name, was a picture of the hardboiled detective; but just that – a picture. A two-dimensional imprint of a three-dimensional being.

It wasn’t simply that Spillane was more reactionary than many of his cohorts, it was that he recognized that what people wanted isn’t depth but excitement, the coolness of a moment, the edgy line, the snappy comeback. The Continental Op could be violent, but he would rather sort things out. Check out the various “tough guy” roles Bogart played in his career and see how little they are engaged in action. When he does play someone who is actually violent and brutal, such as In A Lonely Place, it is a decidedly unsympathetic role. “Down these mean streets a man must go” after all “who is not himself mean.” Mike Hammer is mean. He’s not here to outsmart you; he would sooner just shoot you.

The very end of Somewhere Within the Shadows, with Blacksad blowing away the corrupt businessman in a fit of righteous anger, echoes the end of Spillane’s I, The Jury: With Hammer executing the killer, who turned out to be his would-be lover: “’How c-could you?’ she gasped. I only had a moment before talking to a corpse but I got it in. ‘It was easy,’ I said.” That’s kinda the energy Blacksad always has about him. Oh, sure, it never appears as trashy, not with Guarnido drawing it, but the burning heart of the book is exactly that – the Mickey Spillane to Talbot’s Hammett. Blacksad solves things with his muscles, with his gun, with his overwhelming prowess. Smarts rarely play into it (we can’t have the mystery overwhelm the reader).

Which is not all bad. Spillane was never a master crafter of words, but there’s a reason he sold so well and so consistently and managed to leave just as a big thumbprint on culture as his detractors[14]. There’s fun to be had with Blacksad, a reason I keep coming back to these books, and will probably order the next volume as soon as it appears in the previews catalogue. It is a trashy sort of joy, the joy of the familiar. The detective story done in the old mode, which guarantees that a strong enough man can make everything right, that there is logic to this world. It is a false promise, but it’s fun to dream occasionally. After all, like most of the reading public, I, too, enjoy salted peanuts.

[1] Just like the endless reactions of the cover for Action Comics #1 or Dark Knight Returns #1 that expect the reader to be “in” on the gag. You are meant to recognize not only the original cover as a reference point, but also the fact that it has been so overtly-referenced it is now neutered of any original meaning – the fact you evoke it again is, by itself, a gag.

[2] Back in 2015, Alex Hoffman wrote about the odd problem of racial representation in a series seeking to engage with the real-world issue through the medium of funny animals. A short while later Disney film Zootopia featured a familiar setting attempting to engage with racial tensions and was met with similarly baffled responses – the creators didn’t quite think their metaphor through.

[3] The Slovenian comic Animal Noir is probably the closest series in terms of playing the notion straight, and even that short series had some tricks up its sleeve.

[4] The Europe Comics website has a decent list of Western comics from the continent – https://www.europecomics.com/reading-list-european-western/

[5] He’s a long-time serving city planner who outlasted four mayors and is obsessed with leaving his mark on the city in the form of large landmarks that often displace weakened populations. It’s roughly as subtle as Alec Baldwin’s performance in Motherless Brooklyn.

[6] Modern New York, which more and more is only affordable to rich people, is very much the child of Moses’ mind.

[7] It is a point made by many before me that there’s something unpleasant about the willingness to commit to the animal nature of beings when it comes to women characters, at least those that are meant to be attractive to Blacksad, who tend to be drawn as full humanoids with an animal head (at best) or wearing some makeup (at worst). They All Fall Down, at least, offers us a main female character more like a recognizable animal.

[8] The comics biography of the real person, Robert Person: Master Builder of New York City, is not a spectacular piece but it likewise makes the smart choice of framing Moses often looking at the city from above or far away: he’s seeing ‘the big picture,’ which means he can’t see all the little details (people) that make it up.

[9] Despite there being very little Blacksad overall I still find myself struggling to remember key details; there’s a big dramatic reveal at the end of this volume and for the life of me I couldn’t recognize the character – just another beautiful dame in animal skin.

[10] Not comics but a close cousin – Jim Steranko’s Chandler, a grab bag of clichés played utterly straight.

[11] Yours truly, despite all the expressed negativity in this article, still read them all, still had this new volume reserved when first announced, and will probably buy the next one as well.

[12] For certain values of “great.”

[13] A fact so appropriate to this article it probably seems like I made it up.

[14] Note 1955’s Kiss Me Deadly, one of the finest (and most out there) film noirs of all time. Packed with maniac energy, the film’s apocalyptic ending is much closer to Spillane’s comic-book roots than his later novels.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply