Garbage ape. Meat helmet. Cat wigs. If you’ve heard any of these unlikely combinations, it’s because Heathcliff fever is sweeping the internet. It’s not the first time Peter Gallagher’s orange cat comic has garnered attention for its surreal take on the funny animal strip, but Heathcliff has worked its way back to the public imagination recently. This is thanks in no small part to a Twitter account “Actual Heathcliff Comics” (@realheathcliffs), but it’s also the strip’s oddball sensibility, and the contrast between that sensibility and Gallagher’s retro drawing style, which keeps people intrigued. Heathcliff is consistently funny, but the outsized, and polarized, reaction it draws online suggests there’s a little bit more at play.

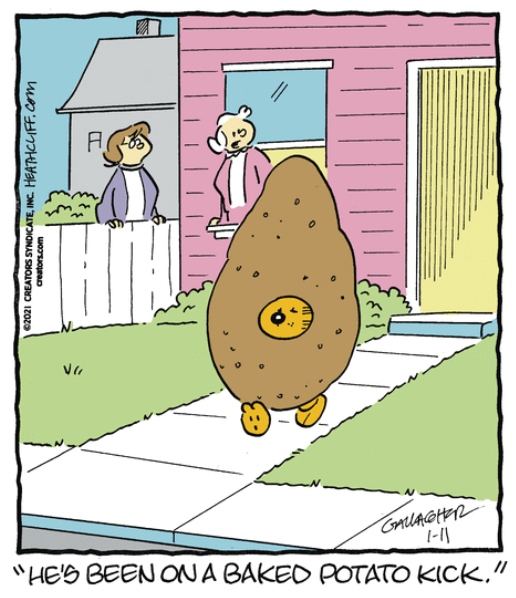

For the uninitiated, Heathcliff is a comic about an orange cat. He lives with an older (human) couple and their (human) son. He likes the stuff normal cats like, like hams, and fish, and helping the dog catcher. An ape, the “garbage ape,” delivers trash on his street. Sometimes he flies using special gum. Sometimes he has a robot, or two. Sometimes he has a tank, the tank says meat on it, and that’s the “meat tank.” Children love the meat tank. Sometimes he wears helmets, which sometimes say “ham.” He has a meat dirigible. No, it doesn’t make any more sense when you read it, but you get used to it. The themes ebb and flow, with Heathcliff engaged in hijinx of one sort or another, always ready for garbage or meat.

Part of what I think might be challenging and delightful about Heathcliff is the feeling that someone, somewhere, is “getting away with it.” It’s just not clear who’s pulling one over on who – is Peter Gallagher, the cartoonist, phoning in his cartoon while schnockered on post-golf martinis? Is Gallagher getting one over on the readers, because the premise is so silly? “The meat tank? I can’t believe you made me read that.” Or is it the syndicate getting one over on us poor readers by publishing stuff like this every day? Certainly the latter might apply for a strip like The Lockhorns, or even Blondie. The not-quite-natural language of these other suburban strips makes them feel alien or robotic, and their presence in the daily papers that populate our youthful memories (because how many of us subscribe to a daily print newspaper anymore? Statistically, not many) feels like a rip-off. But, crucially, unlike Blondie (which might be sort of a ripoff) Heathcliff is funny.

It shouldn’t be surprising that a comic is funny, but it is. This is, I think, largely a response to the growing cultural consensus that, putting aside a few rule-proving exceptions like the “New Nancy” phenomenon, syndicated comics just aren’t funny anymore. In a moment where comics criticism has disavowed the biff, bam, pow and also the honest ‘ha ha ha,’ the stale legacy strips make an easy target. It doesn’t help that many of these older strips, on their second or third creative team after running for more than half a century, actually aren’t funny. Josh Fruhlinger of Comics Curmudgeon fame, who was reading the daily comics back when it actually was kind of a wasteland, has a running gag about the Beetle Bailey universe of strips. The strips, Fruhlinger maintains, are written by “Walker-Browne Amalgamated Humor Industries LLC,” a corporate firm which employs a writers’ room to craft their jokes. Archie, meanwhile, is written by the Archie-Laugh-Generating-Joke-Unit 3000, which procedurally imitates human speech by means of an algorithm, e.g., this post and passim. If it seems like I’m relying on Fruhlinger to make my point here, it’s both because his blog is a significant archive of syndicated comics of the last two and a half decades and because Frulingher, as much as anyone, drew attention to how weird syndicated comics got while newspaper readership dropped across the country.

Rather like a failing mall, the funny pages showed up to work even as audiences dwindled, and as corporate mergers in newspapers – and comics syndicates – meant the audiences had less and less to see. Heathcliff, incidentally, is distributed by Creators Syndicate, which pioneered creator ownership of their own comics. It was no Lord of the Flies, but things did get pretty weird in that empty mall; Funky Winkerbean, for example, did not one but two time jumps, aging up its nerdy teen failures into nerdy adult failures. Mary Worth has done a series of bizarre and variously tasteless story arcs about drug addiction, which isn’t what most people come to Mary Worth for. Liberty Meadows’ persistent but vague horniness was off-putting for a strip mainly featuring talking animals. Perhaps any comic strip becomes weird if we just run the clock out; even the squeaky-clean malapropisms of the Family Circus become bizarre if you contemplate them happening for 60straight years.

Heathcliff is hardly the first surreal comic; Gary Larson’s Far Side is the classic example, and B. Kliban’s cryptic cats (and nudes and nonsense poetry) graced the pages of Playboy for years, and still grace any number of mugs and tchotchkes. Heathcliff probably most resembles Kliban’s work, except that Kliban developed his own highly distinctive idiomatic visual language, one which is still legible even in the versions reduced for easy reproduction and sales on touristy hats and mugs. If we stay with the commodity form, we can think through another connection here, which is between signification and standardization in comic strips. Kliban’s cats are available to purchase bedecked in the items of what Barthes might call “Hawaiianicity,” or those images which signify “Hawaii” as though in language. Although he disparaged his own neologism, Barthes’ used “Italianicity” to describe how a pasta advertisement invoked everything, from pasta to opera, which might evoke in the advertisement’s audience, readers familiar with these clichés, the general feeling of Italy.

I draw on Barthes’ concept of Italianicity — and digress through Kliban — because I think Heathcliff invokes through its visual style and its gag-a-day pacing “suburbanicity” in the particular way that “legacy comics” do — the timeless world of insistent repetition with a difference, both nonspecific and slightly different each day. In some strips, this suburbanicity is a banality, like the cat in the culturally appropriative Hula costume, meant to sell by virtue of its ubiquity and its taken for grantedness. It signifies by representing, it is sketched in shorthand to call on our entire vocabulary of the (white) suburbs, a vocabulary common to so many legacy strips because the “legacy” was cemented by and in the representation of largely segregated postwar suburbs.

In a text which visually resembles the “legacy strips” which reheat and rehash the same handful of jokes – Dagwood is hungry, Garfield is lazy and hungry, Sarge is lazy and hungry and mean, kids say the darndest things in the Family Circus and Dennis the Menace and Hi and Lois, and so on – Heathcliff perpetually surprises us. As Stephanie Boluk writes in her analysis of the “end of history” in Blondie, as in most legacy strips, “time passes, but nothing changes.” A “temporally arrested non-place and non-time,” Blondie reflects the assembly-line optimization of strips which came about with the mass manufacture of the nationally syndicated comic strip and the “iteratively homogenous” content of the strip, grounded in the 1950s suburban isolation. Are these strips any weirder than older syndicated comics? Likely not; Little Nemo is an agreed upon masterpiece, and its whole deal is being weird, Pogo is somehow supposed to be a possum, and Dick Tracy is, well, Dick Tracy. But Heathcliff is a slightly different kind of weird; the garbage ape and the meat tank are both essential to what Heathcliff is and feel perpetually slightly wrong there, just odd enough to remain funny and unexpected.

All comedy works, at least in part, by pattern recognition.The comedy “rule of threes,” for example, says that audiences find things increasingly funny through repetition – and once they learn the pattern, they enjoy the surprise of a text breaking that pattern, introducing an unexpected element or missing a “beat.” Heathcliff works across two registers of making and breaking patterns; the first is the syndicated comic, the expectations for which we established above. Heathcliff fulfills some of these, through the old-timey hat and moustache on Grandpa, the frilly apron on Grandma, the kid’s striped shirt, the suburban milieu where each house has a yard and each yard has a child. Heathcliff plays with our generic expectations by populating these yards with characters from other genres — robots, in one case, or a store selling cat wigs. The second register is the strip itself, as readers get used to the pattern of the strip and then are surprised by some new addition. This is common to all humor comics, and when strips fail to generate this mild surprise, humor breaks down.

In Blondie, Boluk describes the permutations as contributing to the strip’s compatibility with cold war propaganda and the capitalist exploitation of syndicated cartoonists. But Peanuts, less of an easy target than Blondie, worked by permutation, too. By Robert Harvey’s account, “a given situation—say, Linus getting ready to leave for summer camp—can be presented for several days, and on each day a different character reacts to the situation in his or her own individualistic way. This method, in turn, lends itself to the creation of set pieces that can be repeated with endless permutations. Schulz once identified twelve such devices, routines to which he attributes the popularity of the strip” (Harvey 15). Comic strip rhythms support a structure of internal expectation building and subversion; Gallagher is able to do so both within Heathcliff and across our generic expectations of gag strips as such.

Modern and postmodern art has a tradition of recombinatory work, from Dada collage to the rediscovery of ornament and decontextualized historical reference in postmodern architecture; I think Gallagher’s Heathcliff uses the readymade form of the suburban gag strip, with its repetitive and iterative formulae, and adds randomness, reintroducing surprise where we expect it least. What Heathcliff resembles, I think, is an exercise in stochastic play, deliberate randomness as part of an artistic process. Probably the most famous example of stochasticity in art is Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt’s Oblique Strategies, cards with suggestions for making art decisions. Some, like “honor thy error as a hidden intention” and “disciplined self indulgence,” are applicable across a wide range of practices – “do nothing for as long as possible” certainly is applicable to essay writing – while others are fairly specific to music, like “change instrument roles.” You could easily imagine Gallagher pulling a card which says “add a label” or “have you tried a dirigible?” before writing this.

The comparisons between Heathcliff and AI or algorithms, which SOLRAD’s own publisher Alex Hoffman has made, but also in the Heathcliff AI twitter account (@HeathcliffAi), make sense here, too. Markov chains, another stochastic form, iterate possibilities which reference the immediate previous form but “forget” previous iterations. They’re funny because readers recognize the garbled input and are surprised at the new shapes from expected variables. This makes Heathcliff, which iterates a joke like the Meat Museum, where Heathcliff either is a simple visitor, has a membership, or is on the board of trustees (4/30/2018, 4/1/2020, 5/7/2020, doubtless elsewhere), the ideal form of the comic strip. Memoryless, like all comic strips, unlike many legacy strips Heathcliff has no guilt or tedium. Heathcliff comes unstuck in time and pilots his dirigible, trains his robot, uses his getaway gum, buys a cat wig, and climbs the steps to his meat museum.

How long will the joke be on the legacy strip? It’s hard to tell. Contrary to perhaps the still reigning assumption, “new Nancy” might be more rule than exception. Mark Trail has a new writer and artist, and Sally Forth has been written by Francesco Marculiano for years, and he’s introduced new, clever, modern approaches to the characters, including Ted Forth’s constrained domestic madness. Bianca Xunise is one of several new artists at Six Chix in the past few years, and even Popeye has experimented with new directions, including having Randy Millholland of webcomic Something Positive take over the strip. It’s not clear to me what economic outcome is driving this rejuvenation; maybe online access to syndicated comics allows the syndicate to invest in these properties without depending on the newspaper market? I hope it never stops. Across every page, let a hundred Heathcliffs bloom.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland, “Rhetoric of the Image” in Image-Music-Text, trans. by Stephen Heath, Later prt. edition (New York, NY: Hill and Wang, 1978)

Boluk, Stephanie, ‘Nuclear Family: Blondie and the End of History’, Extrapolation, 58.2–3 (2017)

Harvey, Robert C., The Art of the Funnies: An Aesthetic History, First Edition (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1994)

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply