The way we share and do things in the world of comics is always changing. This couldn’t be more true right now. With social media and their online presence demanding attention, artists are always finding ways to make the internet work for them. To talk about the new wave of social media, staying inspired, and how to navigate it all, is Brian Ralph, writer and illustrator of Daybreak.

Ashton Rice (AR): Concerning the awards you’ve been nominated for in comics, what is your favorite/most notable one and why do you think you were selected?

Brian Ralph (BR): You know, the Eisner nomination was really crazy because that was my first published book. I was young and I wasn’t anticipating that to ever happen. It was up against Frank Miller. Frank Miller’s 300 was one of the other nominees I was up against and I was like “Holy smokes,” I kind of thought “I’m not gonna win this,” but I was excited that it put me on the map a little, it raised interest in my work; just to be nominated. Just to have that next to your name as an Eisner Award nominee carried a ton of weight. Even though I didn’t win it, I realized this really skyrocketed interest in my work. The next day after the awards ceremony, people were coming over to check the book out and I could tell that it got the name out more than it would’ve. You know what was really cool? Daybreak went to number six in the hardcover graphic novel section of the New York Times Best Seller List. That for me was really big. The publisher sent me the screenshot and I thought they photoshopped it! It’s one thing to get notoriety within comics, but to have it break outside of comics was just awesome.

AR: It seems that anywhere you see the name Brian Ralph, good things follow. I couldn’t find any negative press on the internet about you, sir. Were you always greeted with such widespread success after your nominations and having made the New York Times Best Seller List?

BR: I have ups and downs. I did a book called Reggie-12, which was a collection of my comic strips that I was doing for a magazine. I thought it was great. This was something that I was super into, and it didn’t get as much interest as I thought it would. I was anticipating cartoon series offers and thought people would be interested in it. I put a ton of work into this thing, I felt it was really strong, but the book didn’t have the same splash that I felt that I had with the other ones. That was pretty humbling. It was one of the first times I felt like I was really having to hustle to get people to even know about this book. It just wasn’t gaining the momentum or the traction that I had anticipated. I liked it, and I look back even now and I’m like, “Yeah, this is great.” Maybe it didn’t catch the same crowd. For whatever reason, it didn’t splash but I know I did the best book I could, so I’m okay with that. You can’t control what other people’s responses are. Maybe it wasn’t the right look, maybe it wasn’t the right year, whatever, but it was the best work I could make at the time so I’m pleased with that. You know, it’s got its ups and downs, Ash. It’s got its ups and downs. The one that you think is gonna be good, turns out to be not that great.

The book, Daybreak, I didn’t think it was going to be this big thing, I thought that one was for me. I thought “I don’t even care about the fans for this one.” I did it for my own sanity. I liked doing this. Who knew that would turn into the biggest of the books published? I had no clue. Who knows what’s going to hit? I don’t know.

AR: You got into some good stuff there. Like you said, sometimes you try to make your winner, sometimes you just wanna do something fun. On that note, what is your creative process, and how do you get a story from an idea and come to actually conceive that into a book? Writing and drawing it, what helps get that process started?

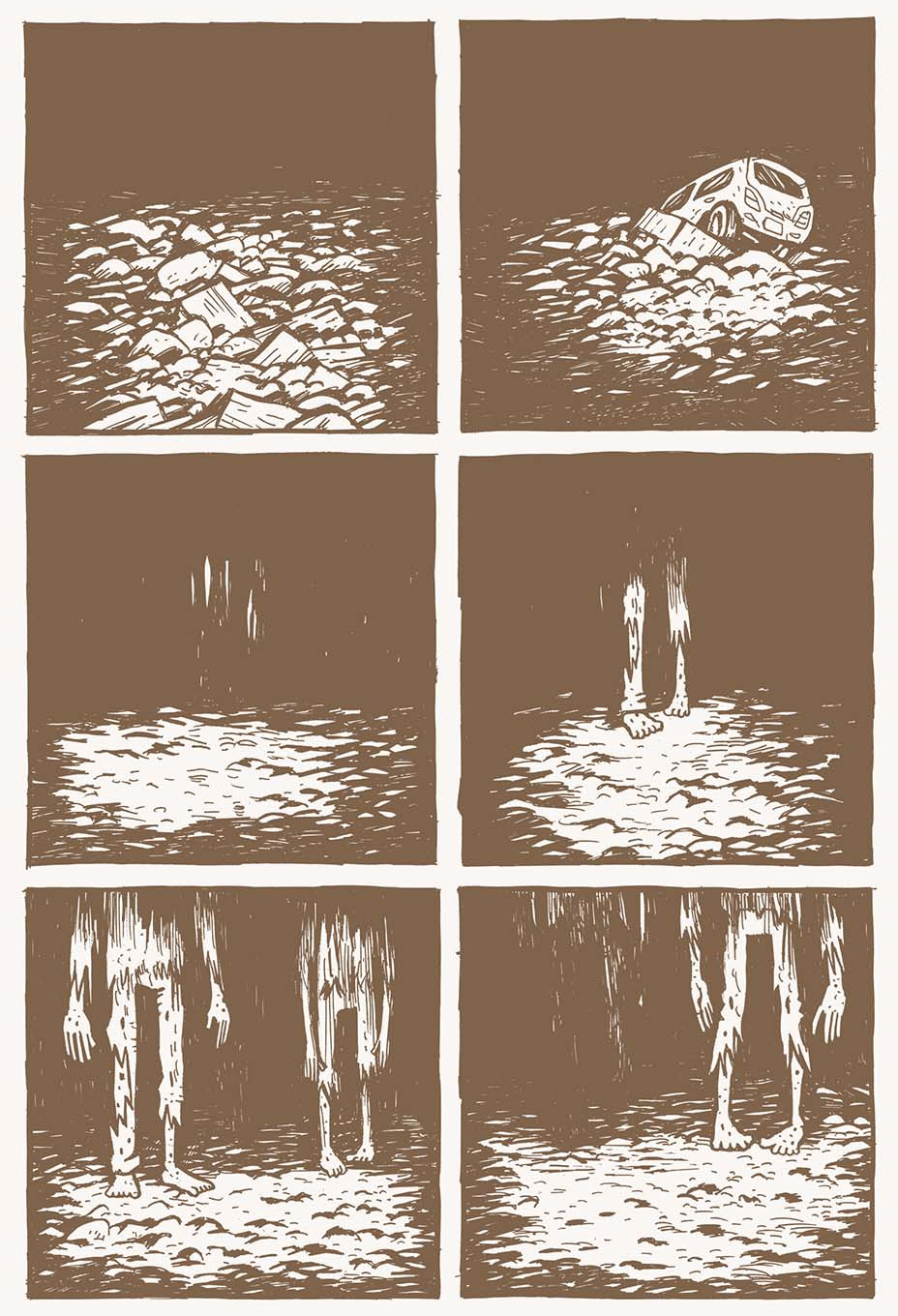

BR: Man that’s a tough one because with Daybreak, I didn’t spend a ton of time conceiving the characters and the universe. When I drew it, it felt right. When I drew out the first page, I was just like…… I was going to go with it. I would warn anybody against over-conceiving or over-planning or too much world-building. If you don’t leave any mysteries in the project, or area for discovery, you might not end up drawing the book. You’ll say, “Oh, I’ve already figured it out. There’s no puzzle left to it for me.” You have to have a little bit of question as an artist to keep yourself thinking, “Oh, I’ve got to figure this out,” and that will keep you coming back to the drawing table thinking, “Oh, this is fun.” You need that engagement. As much as I’m trying to engage the audience in what’s happening, I’m also trying to engage myself as the artist because you’re going to have to sit there for hours drawing this thing, so it’s going to have to have a little fun to it. If you’ve already got it all figured out, I feel like it’d lose the fun to it.

AR: Even as inexperienced as I am, I’ve taken some commissions where it’s been so planned out for me and I’m like, “Oh my God…”

BR: Yeah! Then you’re just drawing something that’s already done, essentially. I like that sense of curiosity like, “Oh, I don’t quite know what this is about yet. I’m gonna figure out some of this as it develops.” So, Daybreak was originally serialized into three books or three serialized stories, and it was really fun to draw a section of it and talk to people. Like fans or readers would be like, “Oh, man! You know what should happen next,” or “Oh, I wonder what this is about,” and I would always listen to what they were saying and I’d think, “Oh man, that’s a cool idea, I like what this person is thinking,” or, “I hadn’t planned that, but yeah, that’s a cool direction.” So anyway, a little bit of that give and take with the audience reaction is fun to have too.

AR: So like you said, when you don’t have it so written in stone, you have room to wiggle and room to feed that fanbase and then also do what you want to do. You know, so you can do it on a whim and do it based on how you feel?

BR: Yeah, exactly. A little bit of mystery.

AR: That’s awesome. So, I’ve also read that you’ve taught at quite a few places. SCAD is only the most recent venture in teaching for you, correct?

BR: Yeah, I used to teach at Maryland Institute, in Baltimore. I taught high school for a year. When I first started teaching, I started teaching workshops for little kids at libraries and afterschool programs. I liked being in the studio and making stuff, but I also really liked getting out and talking to people. You take for granted this art. You just do it and you don’t think much about it. You’re just good at it. But when you teach it to other people, you realize, they’re super excited to learn it and they don’t know how to do it, and you get to share this expertise with them and it’s really rewarding.

AR: To that point, how did you make sure that you were the best teacher that you could be? How did you bring your successes along with you and translate that into the classroom?

BR: You know, what’s funny, I think about it the same way you try to tell stories or draw, you’re desperately trying to communicate with an audience, and if the readers don’t understand your story, you failed at telling it. The same thing with your class. If your class doesn’t understand what you’re trying to say, or they’re not making good work, you gotta figure out how to get ‘em excited or how to explain it better or something to communicate. I think for me, it’s this desperate need to communicate to people, or try to get them to understand. I’m always trying to figure out new ways to teach things, or more concise ways to teach things.

AR: Obviously, like you said, you wanted to teach, you wanted to spread the knowledge, but also, you wanted to make your own stuff. You were on a roll. How do you balance the two? How do you come in and teach such hyperactive adolescents and still have enough left to make such great artwork and stories come to life?

BR: That’s really hard. Especially if you’re teaching art or something you love. How do you have that love at the end of the day? Do you have anything left in the tank to try to do your own thing? That is a hard thing to balance. You have to shut off your brain at some point. Like when you’re making your own work. I’ve been critiquing work all day and working out problems. At the end of the night, I have to shut all of that out and go back to the purest form of just trying to have fun and remember it’s fun to walk this character around and do things with this character. I don’t overthink all the critiques. I know all of the problems, I know all of the things you can do wrong. But you have to let your brain experience it at the drawing table. It’s really hard, it’s hard. Every single thing I set down to draw, I’m just like, “Oh yeah, I’ve seen this before,” or “Who am I borrowing this idea from?” You can’t overthink it. I just trained my brain in a way to shut off and get into it and have fun. Don’t overthink it. Social media helped me with that too. I stopped being quite so precious with every single thing that I was drawing. Then you don’t end up drawing anything. You can just go, “Yeah, I’ll just post this. This is fine. Good enough.” Getting to that point was hard, but it’s just like, “That’s good enough, that’s good enough.”

AR: So when your brain isn’t turned off, how are you actively trying to get students published? How are you trying to get them to the same kind of success you see?

BR: That’s a good question. What we’re trying to do in class a lot is….You have to realize your skill is not just drawing comics. Your skill is in a lot of different places. It’s not just about anatomy and perspective, that’s just one piece of it. The rest of it is writing, storytelling, coloring. There’s so many aspects to this that you can be successful at. A part of it is some of those intangible things like just being an interesting person, being able to talk and meet with people in person, being able to have that little nuance to your work that somehow resonates with people. There’s so many tangible things you can do to learn how to draw, how to tell a story, but there’s all these conceptual things. Like hey, are you reading and watching movies that are feeding your interests? Are you out there talking to other artists? Are you out there getting inspired? You know, what kind of music are you listening to? You know; how are all of these other things you take in, helping your work? So some of the things we do in class; we learn how to talk about each other’s work, we learn how to critique, we learn how to get over our fear of speaking in public. Those are all these other aspects to being a good artist that no one talks about. If all you’re good at is just drawing, you’ve only uncracked like one level. There’s all this other stuff you have to learn how to do. Some of it is just engaging people in real life. Can you go to a convention and talk to somebody that comes up to your table? Can you sell your work to them in a good way? Can you have that rapport with other people? That’s a big part of it.

AR: Yeah, that personality aspect of it.

BR: Yeah, exactly. Now with social media, people don’t want to just see your work, they want to know what you’re like as a person. They want to almost buy into the whole world of what you do. Not just one page of your drawing, but like, how does this fit into your whole aesthetic? I can see that as a new part of it. Being able to see all of your favorite artists not just by their comic book, but to be able to see their cat, and to be able to see what their studio looks like. That’s a big part of how this is expanding.

AR: Beyond being a teacher, beyond trying to find success for yourself; if you ran across someone that came to Savannah or was just walking through your neighborhood someday and they wanted to become a writer or illustrator of alternative comics, what is the best advice you could give that person? I’m talking about alternative comics in particular. What would be the best advice you could give for success in that specific genre of comics?

BR: So, you gotta do it yourself. Everybody has to start any business by doing it themselves first. No one’s going to come and grab you out of obscurity. You have to be self-publishing, pushing your own work, hustling your own work. Like getting noticed…… there was an alumnus that……oh! Jeremy Nguyen! Jeremy Nguyen came into class and [said] the same thing, you almost have to demand attention. You have to find a way to demand attention. Your Instagram, your social media; you’re posting work, you’re building a fanbase. You’re hustling any way that you can to get your work out there. I started by self-publishing minicomics and going to conventions and handing out prints or giving away minicomics to other artists that I like, and I just did it because I love it! But, in a way, I was sort of putting myself out there. I was demanding attention in a way. I was like, “Here’s my work.” I think the goal is to get a publisher to join you. They get the right to work with me, not the other way around. Not to be boastful, but that’s the way that you have to think. Like when I was making my own minicomics, I was trying to compete with other publishers. I was going to make as many minicomics as I can, and almost make a publishing company of my own. What happened was, people take notice, they want to get in on what you’re doing, and they say, “Hey. You come and do a comic for us,” and that’s how it happened. So I wasn’t really seeking out publishers, I already had my own DIY business goin’, and then publishers became interested.

AR: So we talked about the positive, and based on your experience — because like we talked about earlier, you have quite a bit of it — what would you warn someone about in the industry? What would you caution someone against?

BR: I think there’s been times when I didn’t know what my brand was, didn’t know what my aesthetic was. I’m torn because you gotta try new things, you have to explore new avenues, but there were times when I was maybe putting too much time and energy into projects that were ultimately not on message and not on brand. Things that weren’t on that ladder to success. They were sort of offshoots and they ended up taking up a ton of time. I didn’t have a defined, clear direction on what I was doing. I was just grabbing jobs and grabbing projects from wherever. Anything anybody ever offered me I would just go and do. I probably should’ve had a better understanding of how I should spend my time and what I should be working on. If you have a clear and defined goal, like a five-year plan, or a ten-year plan, a life plan; if you’re like, “Hey, here are all the things I want to accomplish,” you’ll be less distracted by random jobs and gigs that come in. You’ll be like, “Well, I don’t really need those. Why would I spend all my time doing that? That doesn’t fit into my life plan. That’s sort of an offshoot that will waste a ton of time. Am I just flattered by the fact that someone offered it to me? Maybe the only reason I took that job is because I was flattered.” I would just say, “Sure, I’ll do it.” If I’d had a plan for where I was going, I probably would have been like, “No that doesn’t fit,” or, “I don’t want to associate my work with that.” That would be a really strong ability, the ability to say “no” to certain projects that don’t fit.

AR: For sure. So what keeps you motivated? What drives you to continue to teach and create after so many years of doing it?

BR: I’ll tell you, I had some ups and downs. I had been doing a bunch of comics and I felt really burnt out. Anytime I felt like things were getting stale, I would get curious about a new idea. Like, “What if I tried it like this instead?” Not just doing the same thing, but trying something new and challenging myself. That kept me excited. Like playing a new video game; learning how to play it, and learning the new rules of it. Rather than just revisiting the same way I had been doing comics for years, I took on a new challenge. “Oh, this one’s gonna be like first person.” That was enough of a challenge for me that it kept me back at the drawing table like, “Oh man! I gotta figure out how to do that!” It kept my brain busy. If you feel like you’re stale, or just kind of phoning it in, you gotta figure out a new way of doing that will keep you engaged and keep you interested. That’s what I do. Some new challenge, something I haven’t done yet. Something that’s on brand, but new. I don’t know, that’s what happened with Daybreak. I was always excited to go back to the drawing table. 11 o’clock at night like, “Oh man! I gotta go do that page!” Whatever that magic is, you gotta ride that, like that flow. You gotta stay in that for as long as you can because you’re probably making your best work with that.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply