I first met Ben Towle in 2005, when I attended the first meeting of a drawing club organized and hosted by Ben. As he explains in the following interview, the group (mock-pompously called the Camel City Cartoonists’ Guild and Social Club) was his attempt to grow a comic culture in his then-hometown of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Ben and I have been collaborators since, most notably on a series of “Mega-Panels”—deep dives into a specific topic like music and comics, the centenary birthdays of Eisner and Kirby, Archie comics—held annually at Charlotte’s Heroes Con. Several years ago, Jennie Law joined us in the mega-panel planning and presentations: we’re now a troika of comics conspirators.

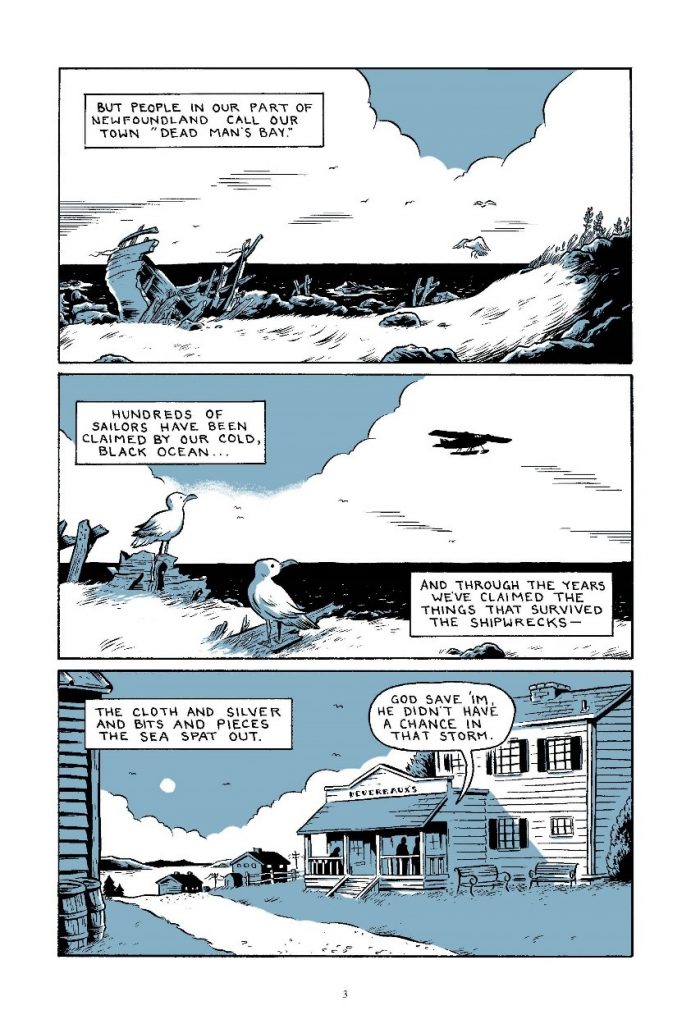

Although my first interactions with Ben were social and professional, I quickly became a fan of his comics. In addition to numerous anthology contributions and self-published minis, Ben has produced five books: Farewell, Georgia (2003), a suite of four Southern tall tales; Midnight Sun (2007), an adventure story based on a true North Pole zeppelin crash; Amelia Earhart: This Broad Ocean (2010), both a chronicle of a girl inspired by Earhart’s achievements and a collaboration with writer Sarah Stewart Taylor; Oyster War (2015), a tale of pirates and excessive oyster farming that veers into magic realism; and Four-Fisted Tales: Animal in Combat (2021), a story collection about dogs, bears, and birds involved in human wars. For his work, Ben’s been nominated for four Eisner awards, and he served as an Eisner Judge in 2009.

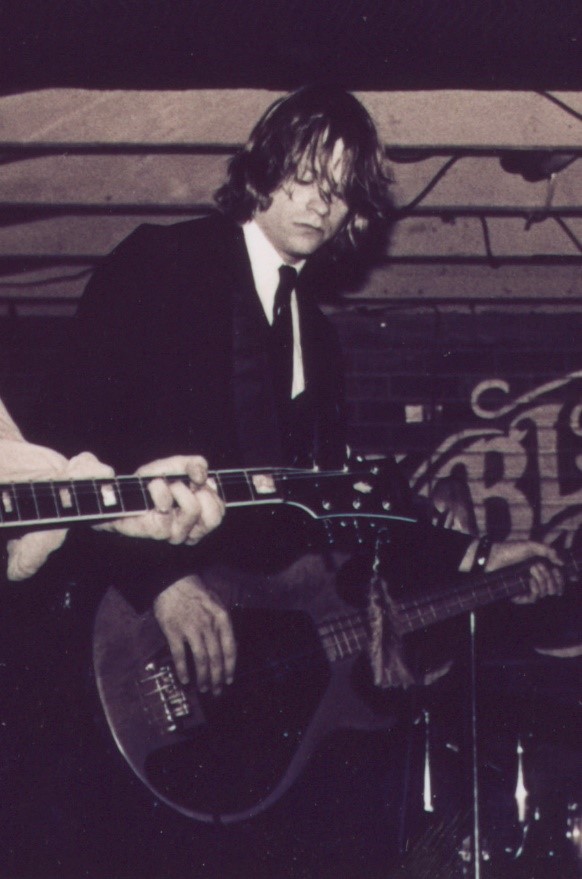

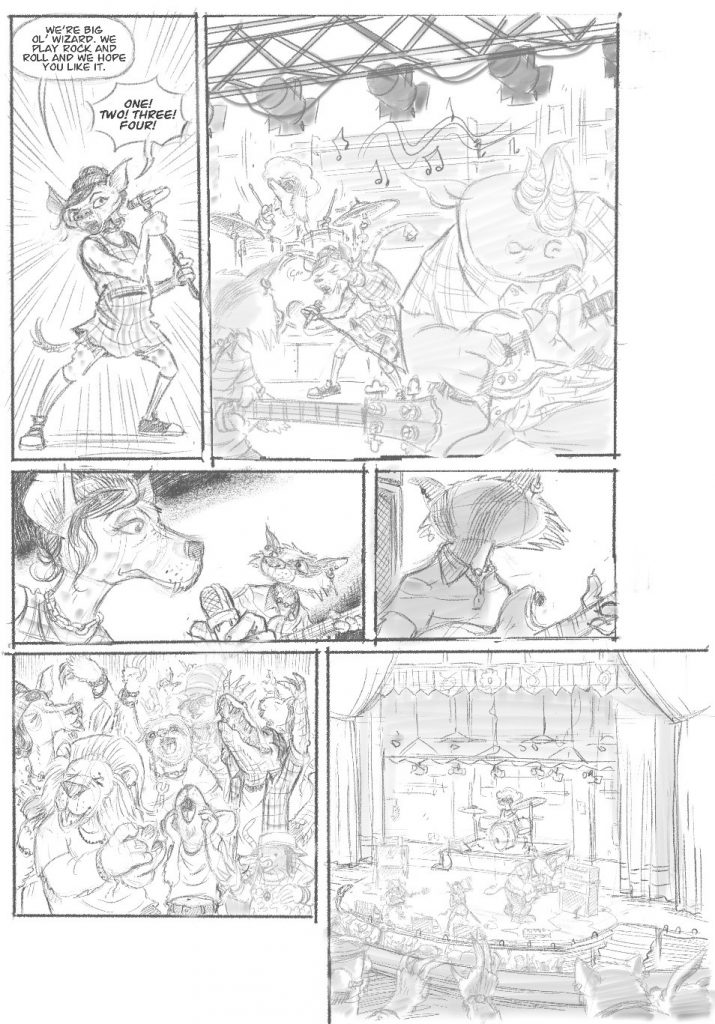

We cover each of Ben’s books in our interview, but we go further. Ben talks about his personal mentors and creative milestones: his role as bassist for the Southern blues-rock band Come On Thunderchild, his time learning from James Sturm and Ted Stearn as a graduate student at the Savannah College of Art and Design in the late 1990s, and his current position as Professor of Illustration at the Columbus College of Art and Design. He also shares passionate opinions with us, especially about the importance that the teaching of practical skills should play in arts education. My thanks to Ben for his frankness, his patience as I transcribed this interview over several months, and for his many years of friendship.

Beginnings

Craig Fischer: Your birthday falls on September 11th, but what year?

Ben Towle: 1970. I turned 51 last year, on the world’s worst birthday. [Laughs.]

You spent some of your early years of your life in Hawaii. Were you born there?

No. I was in Hawaii because my dad was a Navy officer; we would move around a lot. He was transferred to Pearl Harbor and we were there for four years or so. My parents divorced while I was there. I lived there for a little while, just with my dad.

Where were you born, then? And where else did you live as a Navy brat?

I was born in Washington, DC, and we stayed relatively centered around Norfolk, Virginia. Norfolk was a huge Navy town—“squids,” Navy guys, all over the place.

So early childhood in Norfolk, and middle grades in Hawaii?

Right. Then my parents separated, and I moved back in with my mom in Norfolk.

Your parents’ separation happened when you were fairly young, right? You’ve told me that you ironed clothes at age eight, just to help your mom out with chores.

That’s because I’m impatient and I wanted my damn clothes ironed! [Laughter.] Being a single mother, Mom had other shit to do. Weirdly, my parents were married, and then divorced, and then married again and then divorced again! I was a baby when they first separated—I don’t remember it—and then they reunited when I was three or four.

This period is all mixed up in my brain because that’s also the time when my dad did ship duty. I remember him being gone for long periods, but in retrospect, I’m not sure if that was because he was on ship duty in the Mediterranean or because of the divorce. When you’re a little kid, you don’t question what’s going on. You go with the flow, and then as an adult, memories fall into place: “Oh, this makes a little more sense now.”

And you have a sister.

I have a half-sister, named Rachel, fourteen years younger than me, who’s the product of my mom and the man she married after my dad. She’s the Membership Director at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, the museum that recently hosted Dan Nadel’s Chicago Comics: 1960s to Now exhibit.

We didn’t live under the same roof for long. When she was a toddler, I was getting ready for college. Recently, we’ve gotten closer than we were at any point previously. We’re both adults, we’re in touch more, and I’ve visited her in Chicago a few times.

What was your comics gateway drug? I know Walt Simonson was a big deal for you.

It depends how far back you want to go.

Let’s go back to early childhood.

We’re both old coots, so we remember when comics were ubiquitous, on spinner racks in drug stores and places like that. But very early on in my life, there was an older woman, our next-door neighbor in Norfolk, who would look after me during the day when my dad was on ship duty and my mom was working. At her house, she had two or three collections of newspaper comics that I would read over and over again. One was a Little Orphan Annie book, and one collected a bunch of Betty Boop newspaper strips—which I have not seen again to this day. I think there was also a Felix the Cat collection, the Otto Messmer stuff.

And then I don’t remember many comics until the Star Wars comics from Marvel, that were published even before the movie came out. Did Howard Chaykin do the covers?

He drew the interior art too.

I remember reading those…but all the instances I’ve described so far felt like seeing a TV on in people’s houses. Just part of the background culture. I knew about Star Wars comics like I knew that Sanford and Son was a TV show, but it didn’t mean I was a hardcore Sanford and Son fanboy. Although I am. [Laughter.]

The real gateway drug stuff for me came when a friend of mine—from either middle school or high school—introduced me to his dad, who owned a copy of Bill Blackbeard and Martin Williams’ big Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics. I routinely borrowed that book from my friend’s dad and returned it, and then borrowed it and returned it, etc. At school, the rumor was that my friend’s dad had a full run of Batman comics, from Detective #27 on: I don’t know if that rumor was false, or he just had the good sense to not tell us where those comics were. [Laughter.] But I read and re-read that Smithsonian Collection, in particular the great E.C. Segar strips in there, and I’m still a big Thimble Theater fan.

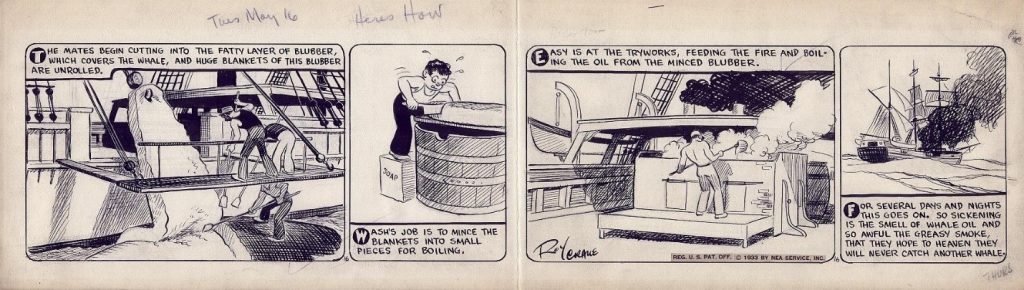

Was that your first taste of Roy Crane?

Absolutely. And I didn’t latch onto Crane as a kid. Later, when I was a student at SCAD [The Savannah College of Art and Design], I was under the tutelage of James Sturm, who was going through a serious Crane phase at that point. He showed me Crane’s art, and I remembered the amazing whaling story in that Blackbeard volume.

The other real gateway for me was Walt Simonson. I’d ride my bike to the 7-11 near my house to check out a spinner rack of comics, and one day I picked up Thor #339, the one with the pink cover, Simonson’s third issue writing and drawing Thor. I was completely blown away by the story and art. And of course, I went back and tracked down #337, and had to pay a premium price of $8 for it. I’ve still got it mint in box. [Laughter.] Though I’ve not had it slabbed. I think I actually have two of them now.

I loved Simonson’s artwork for some reason—for some reason? Because it’s amazing! And I read it at the right point in my life. That comic came out in late 1983, when I was a 13-year-old boy, and that’s the perfect age for superhero comics.

Did you get that 1984 Baxter reprint of Manhunter at around the same time?

You bet! I went on a big Simonson tear, and I still have that Baxter reprint. The cover’s falling off that comic. And I love it. I’ve acquired all the Detective issues that have Manhunter as a back-up story, but when I go to re-read those stories, I go to the beat-up Baxter. I also loved Star Slammers, Simonson’s Marvel / Epic graphic novel.

If you look through my early teenage sketchbooks, there’s a lot of half-assed work—imagine Simonson drawing something with his left hand after a stroke. [Laughter.]

Did your lettering look like John Workman’s?

I didn’t notice the lettering as much as a kid. But it was such a big part of Simonson’s visual style during that period. It was like my response to Roy Crane’s art—I only put it together later.

Now I look at Workman’s lettering and I see how fantastic it was. The whole package was like Jack Kirby crossed with Sergio Toppi, but you don’t know that as a teenager. But after Simonson’s Thor, I really got serious about comics.

Somehow, I’d gotten wind of the fact that Simonson had gone to the Rhode Island School of Design; he went to school to become a comics artist. This is the moment where I realized that this is a job that a person does—there’s a cartoonist with a sheet of paper, and they draw the pictures, and eventually their comics show up at the 7-11, you know? This is a profession. I can learn to do this.

So I started looking at more comics. My mom would drive me to a comic book store called the Trilogy Shop in Virginia Beach, where I would buy comics, and I would mail-order stuff as well.

You didn’t have a comic shop in Norfolk?

They must’ve. I don’t know why I latched onto the Trilogy Shop. But once you get out of the spinner-rack world, there’s a whole new world of comics there, especially in the mid-1980s, during the black-and-white boom. And sure, a lot of garbage as well, but everything’s interesting when you’re learning about a medium. While I kept reading superhero comics—mostly Marvel—I also discovered Flaming Carrot and Neil the Horse and Elfquest and Alan Moore and Steve Bissette’s Swamp Thing and Moore and Gibbons’ Watchmen and Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, though I didn’t necessarily understand a lot of it. I remember reading the first issue of Dark Knight Returns, because it was supposed to be this big deal, and I thought, “I don’t know what this is about.” [Laughs.] And I was really into Miller’s Ronin, though it confused me.

Me too, and I’m eight years older than you.

At least I read most of Ronin as it came out, whereas with Dark Knight I read the first issue and decided it wasn’t for me. And as a 13-year-old boy, I loved Miller’s Daredevil: it’s about a dude who beats up ninjas, and it’s funny, and it’s easy to follow. It’s not high-concept. But it’s only later in life that I came to appreciate Ronin and Dark Knight Returns. In fact, I’m making my way through the giant Ronin Gallery Edition right now.

You do analytic tweets about the Gallery and Artist Editions that you own. You also wrote a series of tweets about the Daniel Clowes Fantagraphics Studio Edition.

I only own four of them, but I love to tweet about the details in the original art. I have the Simonson Thor book, the Dan Clowes one, the Ronin one, and Bravo for Adventure by Alex Toth. I would own more, but they’re a little rich for my blood, you know what I’m sayin’? [Laughs.]

I had the same epiphanies when I discovered the Direct Market and comics like Neil the Horse and Love & Rockets. In the Buffalo, NY neighborhood I grew up in, there were eight places where I could buy comics within a two-mile radius of my house.

It was an excursion for me. I had to get Mom to take me. I eventually started mail ordering comics. Back then, you got an envelope that listed the items in next month’s Diamond shipment, and you would check off the comics you wanted. And you’d put your dad’s purloined credit card number on the form, and then mail it back to the pre-order company—one of those mail-order services that advertised in the back of comic books, maybe Westfield?—and you’d eventually get a box of comics.

Were you able to order underground comics from this company?

I never saw an actual underground comic until I was in college. In fact, I remember dropping off a friend’s girlfriend on the way home at the end of a school year, and she had tons of underground and alternative comics. In retrospect, a very cool girl. I looked through her collection and saw Wonder Wart-Hog and the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers. I’d never seen that stuff before! I’m still in touch with her. She lives outside of Asheville, and I went to see Tame Impala with her, and she still has an amazing comics collection, tons of long boxes, including all the magazine-sized issues of Love & Rockets and all the Lone Wolf and Cub issues with the Frank Miller and Bill Sienkiewicz covers. Nary a Marvel book. All independent comics, alongside her Sonic Youth 12-inch singles and other records.

North Carolina and Davidson College

So you spent your teen years in Norfolk. Did you and your mom move to North Carolina together?

No, my mom stayed in Norfolk. I moved to North Carolina when I was accepted to Davidson College, outside of Charlotte. And besides the years I went to Savannah for graduate school, I lived in North Carolina until three years ago, when I moved to Columbus, Ohio to teach at the Columbus College of Art and Design.

When you started college, you had a gap where you stopped reading comics for a while.

That’s right. That gap seems to be a phenomenon with men my age. I enjoyed what I found in the comic book shop, in the Direct Market, but in my later years in high school, I got more involved with socializing and girls and music. In college, I tried to read Dark Knight Returns again, but I still didn’t connect with it.

In post-college, though, when I was playing in a band, most of the members lived together in a house, and John—our singer—was a comics guy. He was really into Hate and Eightball, and, to a lesser extent, Mr. X: the kinds of indie comics you could find in record stores in the 1990s. A lot of independent record stores would have a rack of Fantagraphics and other small press books, mixed in with local zines and old undergrounds.

Our communal house was in Charlotte, and at the time Heroes Aren’t Hard to Find carried alternative comics, on the rack farthest from the superhero comics. [Laughs.] I assume that Dustin Harbin curated that rack at the time. You could discover stuff at Heroes like new Fantagraphics and Drawn and Quarterly books. That’s how I reconnected with comics, but that would have been in my mid-twenties.

I think this gap was common in my generation for a couple of reasons. The standard narrative in histories of comics is that 1986 brought us Maus, The Dark Knight Returns, and Watchmen, and everybody loved them. But there was nothing to follow them up, which created an attention gap. The revolution was, in fact, not televised. [Laughter.]

I read those books, but I read others too—American Flagg, Thriller, Wasteland…

Fantasy books like Elfquest, and interesting science fiction like Alien Worlds and Alien Legion. Heavy Metal was percolating at that point too; it’s perpetually threatening to gain a toe-hold in the U.S. [Laughter.] But Heavy Metal was verboten for me because I was too young for chrome big-titty robots. [Laughter.] “I don’t wanna get caught with this…”

I hid my Best of Heavy Metal collection from my parents, for obvious reasons. [Snooty voice:] “I bought it for the Moebius.” [Laughter.]

Back to those black-and-white comics of the 1980s: there was more going on than the comics histories acknowledge. Anthropomorphic animal comics were huge. Everyone talks about Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, but what about Omaha the Cat Dancer? And indie superhero comics from Pacific and Malibu, and other genres too. Ms. Tree! Only as an adult did I realize that Ms. Tree sounded like “mystery.” [Laughter.] It was an interesting time to be a comics reader.

There’s this huge swath of neglected comics published from 1986 to 1996 that I missed. When I got back into comics, I completely missed early Image: it was such a phenomenon, but I don’t know anything about it. And I missed Jhonen Vasquez’s work at what was then called Slave Labor Graphics.

Slave Labor also published Evan Dorkin.

The reason I submitted my early comics to Slave Labor was because I associated them with Milk and Cheese and Dorkin’s Hectic Planet, and Zander Cannon’s The Replacement God, which is an absolute favorite of mine that no one talks about. And Action Girl. And I thought, “Oh, I’m sure they’d be interested in publishing my dumb stuff.”

I was completely unaware of Johnny the Homicidal Maniac and Roman Dirge’s comics. I only learned about them in retrospect. I was at the San Diego Comic-Con signing books, and suddenly the space in front of my table filled up with super-hot goth girls waiting in a single-file line to meet Jhonen Vasquez. I was confused: “What are girls doing at this comic book convention? Something is wrong here! There are WOMEN!” [Laughter.]

Dorkin’s comics and Sarah Dyer’s Action Girl were comics heavily influenced by music, especially ska. Maybe you found those in record stores.

Definitely. Not to be too Gen-X about it, but comics like those dovetailed into the 1990s DIY aesthetic—comics, like music, became an artistic pursuit that you would do yourself. Self-publishing: we do not speak of Dave Sim now [Laughs], but that ethos was in the air. Comics and music were lumped together as low-fi, low-cost DIY media, and everybody was out there “jammin’ econo.”

Let me return to some personal questions. Why did you go to Davidson College, and why did you major in Philosophy?

I went to Davidson because my mom suggested that I apply there. I had other schools in mind, and my mom said, “You know, you should check this school out.” We went on a big tour of colleges, we visited Davidson, and it clicked: “This is where I want to go.”

I’m wondering why you didn’t major in art, like Simonson.

That’s when I wasn’t reading comics anymore, during my “gap period.” I was still drawing, but it never occurred to me to study Art. I wanted to major in Biology—Genetics in particular—because I loved Biology in high school. And when I was a freshman at Davidson, I took a Philosophy class only because it fulfilled a general education requirement, and I thought, “Oh my God, I love this.”

Was it a Logic class?

No, it was Introduction to Philosophy, where we read various essays, starting with Plato and Aristotle and continuing through Descartes and moving up into modern philosophy—though nothing as complicated as, say, Wittgenstein. It was a survey class, where we’d evaluate each argument and say whether we agreed with it or not, which appealed to me, since I’m a somewhat logical person. I like problem-solving and evaluating things. So I decided I was going to be a Philosophy major. The teacher was charismatic as well.

It’s important to have a good teacher for abstract subjects like that. Makes a big difference, especially early in your college career.

I liked a lot of my professors. And given that I became a Philosophy major, I obviously didn’t think even the tiniest bit about whether I would be able to make any kind of a living. [Laughter.] I have an accumulation of degrees that are not the world’s most practical degrees.

I did some art in college. I drew, I kept a sketchbook, and I took an etching class, which I absolutely loved, with a visiting Art professor named Andy Owen. He did large-scale prints where he’d hire a steamroller to roll over his plates. I was doing zinc plate etching, which I still want to get back into, but it’s complicated, the opposite of DIY: you need a press, an acid bath, etc. But there’s something appealing about laboring over a single image that you don’t have with comics. In comics, I bang out a panel and move on without obsessively worrying about the single picture. And readers don’t linger on a panel. But when you’re etching or painting, there’s a permanence that encourages you to really focus on crafting a single image.

I also took a painting class from a fairly well-known contemporary artist named Herb Jackson, who has art up in the Bank of America tower in Charlotte…which is funny, because his work is completely abstract. I liked him, but I hated the class. The supply list for the class was paint, and a brush as big around as a baseball—so you couldn’t paint anything figurative. He didn’t teach color theory or how to mix paint, but you’d keep a “dream journal” and just paint whatever you felt like! And I thought, “This is some bullshit, man!” [Laughter] “I want to learn how to paint a bowl of grapes!”

In your interview on Dan Barry’s podcast, you expressed a real impatience with art that was only about personal expression, and nothing else.

Yeah! In retrospect, I should have taken better advantage of that class. I remember visiting Jackson’s studio, a beautiful studio in Davidson, and looking through his flat files and seeing his art from when he was in his late teens. It looked like my work, figurative drawings of demons and monsters, the kind of dumb stuff you draw when you’re 18 years old. And it clicked: it’s not that he doesn’t know how to do this. He’s decided not to do this. And maybe there’s more to abstraction than there seems to be.

Certainly when I teach, I don’t tell my students, “Here, go create! Follow your muse!” I think that drawing is a skill that can and should be taught.

You have to put in your 10,000 hours to master drawing.

Exactly. Probably some people are more predisposed to certain abilities, but the bulk of drawing is the practice that builds up skill. If you want to learn to draw comics or illustration, you absolutely can be taught to do so. The belief that the ability to create art is some sort of mystical gift—imparted by fairies of whatever—leads to undervaluing artists, philosophically and monetarily. If we assume that drawing comes easy to an artist, people take it for granted and assume that it’s easy…and then people expect you to draw for free. You wouldn’t expect a plumber to fix your garbage disposal for free, for “exposure,” because everyone views plumbing as a learned skill that deserves compensation. People tell me, “Oh, you’re so blessed with this talent,” but I wasn’t blessed with anything! I’ve been doing this for 20 years, and I’m still not great at it. It’s really difficult work, you know?

Rock and Roll

You’ve done a little screen printing…

Yeah, a little bit.

Have you done any gig posters?

Only for my own gigs.

Right, for your band Come On Thunderchild.

My posters were always typical of the 1990s, always low-fi—basically a black and white image, and if you were super-fancy, you would print it on some colored paper. I never got in on the ‘90s gig poster deal, and I don’t know why, since that was obviously a thing back then.

And still a thing now, with the Flatstock poster show and other events. Did you meet the members of Come On Thunderchild at Davidson?

They were all Davidson students and had been playing in a permutation of that band. By the time I’d got involved, everybody had graduated, but they were still around the Davidson / Charlotte area. I got involved with the band a year after I graduated.

During that time, you were also working in odd jobs like food service, right?

Yeah. I’d started working in restaurants to have money while I was in college, kept on doing it after I graduated, just to pay the bills. And I didn’t want to go immediately to grad school.

Your plan back then was to go to grad school for philosophy?

Yeah, after a year off to work in restaurants, drink beer, and hang out with my friends. [Laughter.] I was planning to study for my GREs during my year “off”—I had one of those thick books with sample tests to help me out—but I don’t know how much actual studying I did. I also briefly considered trying to get into law school, since Philosophy majors generally do well in Law. But I abandoned that idea because it was actually practical and would have earned me a living. [Laughter.]

It’s also more debt.

Right. It would have been really expensive.

The first plan was to apply to a couple of grad schools in philosophy. And at the same point, I’d been playing bass for a while, and a couple of the guys from a band that had been kicking around Davidson had lost their bass player. They asked, “You want to sit in with us? You want to play?” And they were making an actual goal of this, not just content to play people’s parties. They had demos and a gig schedule. They were trying to do this as a career.

This offer was appealing, so I let fate decide. I applied to two “pie-in-the-sky” graduate schools, figuring if I get into one of them, I’ll do that, and if not, then I’ll join the band. One of the programs was UC Berkeley, which was the best Philosophy grad program in the country at the time and probably still is. The other was UC Davis, another great program…and needless to say, I did not get into either of those. Then music it is! The tea leaves have aligned such that I’ll do music instead of academia, for the time being.

How long were you in the band?

It seems like a long time when I think about it, but only three years.

You did regional tours, right?

We were based near Charlotte, and the farthest north we went was New York City, where we’d play every once in a while. The farthest west we toured was Nashville, and the farthest south was Savannah. That was sort of a touring region back in the day: you could do sort of a North Carolina-South Carolina-Virginia-Tennessee loop. If you had a booking agent who knew what they were doing, you could, you could run that loop every weekend—leave on a Thursday and play Thursday, Friday and Saturday night, and then come home on Sunday.

So that’s what I did. We toured on the weekend and I kept my restaurant job on the side. I’d work during the week. Occasionally we’d tour for two weeks, but that was the exception rather than the rule. I balanced both because touring alone wasn’t enough to pay the bills.

I never pocketed money from the band…it all went back into paying for gas or repairing the van or buying gear. Come On Thunderchild was not a money-making venture. It was fun, but not lucrative.

Tell me the wildest thing that happened on the road.

I don’t know if I have any juicy road stories. But it was a rock and roll lifestyle. We’d roll into town and soundcheck, and then we’d get free beer and play. We’d sleep on people’s floors; a few times I slept under a catamaran on the beach. Very fun, but not a lifestyle for a grownup.

We had a tight social group at the time, and folks who didn’t have to work on the weekend hopped in the van with us. They’d come along and get free beer and see a couple of shows and wind up in Charleston or Nashville or Knoxville for the weekend.

When did Come On Thunderchild cut the record?

I think it was 1996. I’m bad with dates and chronology, but I think 1995-96. We recorded it for a small indie label, PC Music, that gave us a very small advance, but they did shell out for four or five days in Studio A at Reflection Studios and Charlotte—their best space, where R.E.M., Southern Culture on the Skids, and other well-known regional bands had recorded. PC Music vanished after a while. Ron Wood had a couple of records with them, and he was their biggest name.

But Thunderchild had a couple of near-breakthroughs before I joined the band. They had done some demos on a Tascam four-track cassette recorder and got some interest from producer Shel Talmy, which didn’t pan out.

When I was in the band, we were really into this Black Crowes record called Amorica [1994], produced by a guy named Jack Joseph Puig. He also produced this band called Jellyfish—kinda poppy, almost like Queen—so at one point I just took one of our demo tapes, stuck it in a mailer, found the address of Puig’s recording studio, and sent it. I included a handwritten note that said, “Hey, we really dig your stuff, and this is what we do.”

A couple of months later, we were sitting around our party house one night when the phone rang, and it was Jack Joseph Puig. He was really interested, and he flew from Los Angeles to Charlotte to see us play at the Tremont Music Hall, and he wanted us to come out to LA and record demos with him. And he was going to shop us around to a major label. (This story appears almost verbatim in a comic I’m working on now about those years, called In the Weeds.)

We had a real crisis of conscience about this because we were already signed to this little indie label, and we couldn’t work with Puig without screwing PC Music over. We were already committed. I can’t remember exactly what happened, but obviously that route—working with Puig—wasn’t taken, but it’s definitely one of those moments where I wonder what would have happened if we had made a different decision. Would we have been signed to a bigger label? Not like that’s a guarantee of success; we certainly had friends who got signed to big labels who we thought, “Oh, they’re gonna be the next big thing.” And then they recorded two albums, the band broke up, and the label kept the masters. So I’m not sitting around thinking, “Wow, we could’ve been Oasis” [Laughs] and pining for that road not taken.

The album came out and got a decent amount of attention…

It did pretty well.

So why only three or four years in the band?

We did okay. We had some good bookings…

Do you get paid more for gigs as a result of the album?

Yes and no. Bookings were always a little contentious. Our manager, who was also our booking agent, had this philosophy that playing somewhere—anywhere—was better than not playing. So sometimes we had these really shitty gigs where we’d be playing for three people on a Wednesday night. And you take your lumps. That’s how it works. It’s a little like drawing mini-comics, and then standing behind a table at a con and selling them. But there’s a certain point at which you think, “I’m paid my dues. This should be getting better.”

We did open for the Allman Brothers and Sister Hazel. We toured for a few days with Government Mule, so we had some good shows. But then it was self-evaluation time. We had put this record out on an indie label, and it had done reasonably well for an indie release. We had some airplay on the local classic rock radio station, and they hadn’t added an independent band to their rotation in decades. But I was turning thirty, and I thought, “What’s necessary to throw into this equation to make it work, how many years will it take, and what’s the likelihood of success?”

And I wasn’t sure if this was what I wanted to do with my life. I was a pretty good bass player, but it wasn’t necessarily my life’s passion in the way that drawing always had been. I had a guitar in high school and then switched to bass in college, but it wasn’t an obsession for me. My house was full of comics, not full of guitars, you know?

But you still have a bass guitar.

Right. I have a couple of them. I still have my two favorite basses. But I kept thinking: do I want to work for another four-year cycle to get another record out and see what the next move would be? We’d probably have to shop ourselves around to a bigger record label, one that would buy out our contract from PC Music. We’d probably have to tour full time too. So I left the band.

And I can’t help but wonder, “Choose Your Own Adventure”-style, what would’ve happened if I’d stayed with the band.

Did the band stay together after you left?

They did, but not for very long. They got somebody else to play bass for a little while, and then the members went their separate ways. They all played in other groups, and some of them still do, but Come On Thunderchild called it quits within six months after I left.

Savannah and Farewell, Georgia

After realizing your true passion was comics, you followed up your time in the band with two years at SCAD.

Two and a half years.

And you taught there as well?

Not at first, but later I started to teach. I got back into comics concurrent with my time in the band, during the mid-‘90s. I drew a few strips for a local alternative weekly in Charlotte called Tangents. The big alt-weekly was Creative Loafing—Atlanta and several southern cities had a franchise version of Creative Loafing—but Charlotte also had an “indier indy” newspaper called Tangents that wasn’t around for long. I did a few strips for them that were embarrassingly bad [laughter], but it was educational seeing my comics in print. My early art was very underground-y looking, full of cross-hatching. Very Robert Crumb. So I started drawing again in earnest during the band phase: transitioning from the band to comics wasn’t a complete stop-and-start.

The two-and-a-half years that you were at SCAD were in the late nineties, is that right?

I graduated in 2000 or right before, so it would’ve been the very tail end of the nineties. I got a Master’s degree there; two years working on the degree, and a half-year lumped on at the beginning to bring me up to speed on foundational classes, since I wasn’t an Art major in college. Maybe that extra half-year was actually to get more money out of me. [Laughs.] SCAD is on a quarter system, and I took two quarters of undergraduate catch-up, along with a couple of graduate writing classes you have to take to get your Master’s.

While you were at SCAD, you studied with at least two comics artists, James Sturm and Ted Stearn.

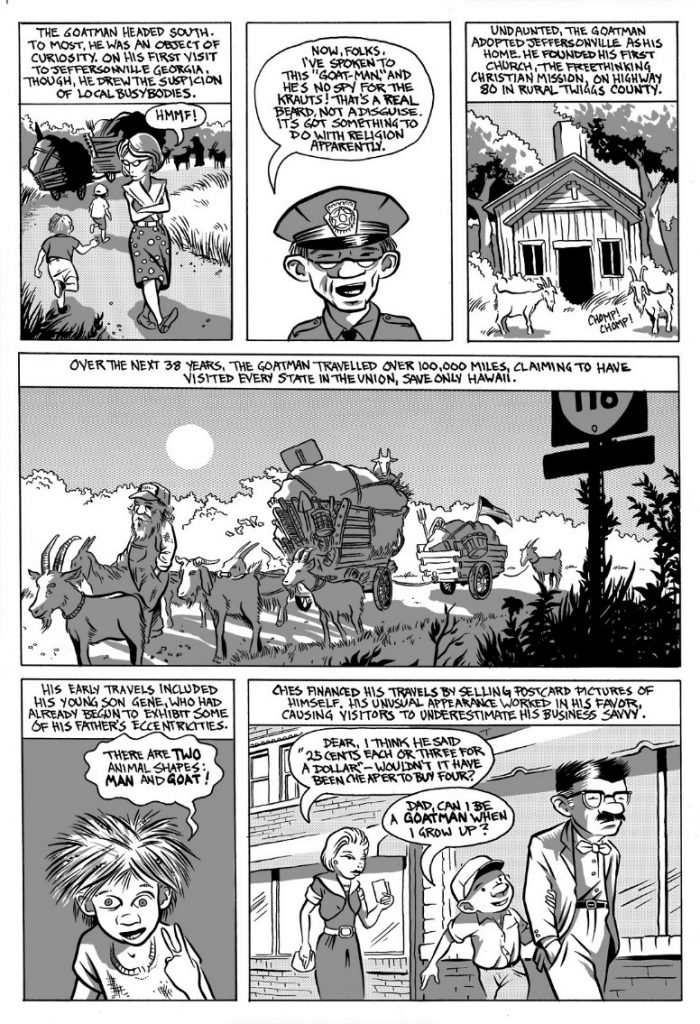

James in particular was a mentor of mine. There were lots of other professors, but I really latched onto James, because he was the indy comics guy. James was influential on my development as a cartoonist. He introduced me to new artists by telling me to “go read this.” It was fun to learn how to ink with a brush and rule a page, but James introducing me to Roy Crane was more important. He was in a big Roy Crane phase because he was working on The Golem’s Mighty Swing [2001] at this time, with its Pantone spot color that emulates Craftint. I still own physical folders of Xeroxed Roy Crane strips that have never been reprinted in any way that does the Craftint justice. And I also have a huge stack of physical Wash Tubbs strips that I bought off of eBay that are cut out from newspapers—that’s the only way you can really see them looking how they’re supposed to look.

James was also into Hank Ketchum. If you look at Ketchum’s early work, you can pick up a lot of minimalist style. He’ll draw a fence and a few of the fence posts, and then the lines will trail off and your brain fills in the gap. You can see both James and me aping that technique. In some of my very amateurish, early stuff like Farewell, Georgia, I’m consciously dipping into that same Roy Crane / Hank Ketchum kind of cartooning.

There was another teacher at SCAD who was a big influence, a guy named Paul Hudson. He isn’t a cartoonist, but he is a traditional old-school illustrator who taught anatomy and perspective. I think he did concept paintings and other work for NASA. Students avoided his classes because they were difficult, but I loved it. Hudson taught the specific skills I had wanted out of that college painting class: this is how you do two-point perspective, and this is how you set up a horizon line. If you want to draw a circular window on a cylindrical object, this is how you figure out how to do it. He would bring little skeletons to class, and have us put clay on the bones, to learn the shapes of human muscles. That’s what I wanted.

Ted Stearn only appeared near the end of my tenure at SCAD: I think we only overlapped by half a year. I remember going out to dinner with some SCAD people where they were interviewing him, courting Ted to come and teach. He was working mostly as an animator then. I didn’t know his comics until he came to Savannah, but then I got some Fuzz and Pluck—I think I first saw it in Zero Zero, and it was great. From talking to Ted at dinner that night, I thought, “This is somebody I need to learn from.”

Ted taught an undergraduate Introduction to Comics class, and since I was a graduate student I couldn’t—and didn’t need—to take this class, but I asked Ted, “Can I just show up in your class?” This’ll date me, but I volunteered to work the slide projector. [Laughter.] And that’s what I did. At first, I was self-conscious and afraid about crashing the class, but now that I’m a professor myself, I’d be grateful if some kid showed up interested in what I was doing and willing to clap erasers and help. And Ted said, “Oh, absolutely”—and I collected papers and worked the slide projector. And the class was fantastic. Ted brought to class that thousand-page L’Association book, Comix 2000, and I’d never seen shit like that in my life!

The first time you saw the work of David B. and other French artists.

Ted also had an encyclopedic knowledge of 19th-century caricaturists and he would do a whole section on caricature. Just incredible. One result of going to graduate school as a thirty-year-old grown-ass adult was that I was somewhat serious about the work; I wasn’t there to fuck around, to drink beer on River Street in Savannah. I had enough sense to realize that I’m in graduate school to learn, and I want knowledge and concrete skills out of this experience.

There were professors who were terrible and they made me fucking angry: “I’m paying for this, and you’re wasting my time.” Which is why I gravitated to people like James and Paul Hudson, and why I was willing to operate Ted’s slide projector. I wanted that knowledge.

I’ve often thought that college serves two cross-purposes: the first is moving away from home and learning to be a person independent of your family, and the second is that you’re supposedly learning some kind of employable skill. And these work against each other. It might make more sense to take off a couple of years after high school to do your fucking around and beer drinking, and then go to college. But for better or worse, those two purposes are forever intertwined in the American “university experience.”

So at SCAD, I was ready to learn, and there were some interesting students there too. Because I was a graduate student, I missed mingling with some of the undergrads, but I was there at the same time as Drew Weing, Joey Weiser, Eleanor Davis, and Max Clodfelter, who lives in Seattle now and who’s responsible for Rooftop Stew and other hillbilly-themed comics.

I was there concurrently with professor Ray Goto—a really good artist—and I think John Lowe was chair of the Sequential Art program when I was there. He’d done work for Archie and some of those good DC “adventure comics,” like Superman Adventures and Batman Adventures. Bruce Timm-ish looking art. Being at SCAD was a great period for me.

You were at SCAD when the famous exposé of the school was published in the academic magazine Lingua Franca.

Right, although the stuff written about in the article happened years before. When that article came out—very tellingly—you could not access it on the school’s Internet. [Laughter.] Mysteriously, that website was not available. And it may be just a coincidence, but soon after James Sturm left SCAD, he did an interview with The Comics Journal, where he made some sort of disparaging remark about the school. I went to look for that issue in SCAD’s library, and it also wasn’t available. “I wonder if this is on purpose, or…? Who else would’ve looked at this besides me? No one else here is probably reading The Comics Journal…”

Farewell, Georgia was your Master’s thesis project.

Another reason I’m glad that I went to graduate school when I was grown up and had some sense. One thing I realized about the program was that at the time it was not geared with the idea that people would walk out of there with a book to submit to a publisher.

I saw people leaving the program, both undergrads and graduate students, with only four pages of their own comics completed, or two color pages and a script they’d written in class. Not even a portfolio, really. Not even enough to put in an envelope and send off to a publisher, as artists did back in the day. In my second year at SCAD, I realized that this would be the last time for a while that I would have dedicated time to draw comics, and in either the last year or the last half a year I was in school, I quit my part-time day job doing computer programming. I just focused on drawing comics.

Even though the program didn’t have it set up so that you would walk out with a finished product, I designed my classes to get Farewell, Georgia done. I took a scripting class and wrote something for the book. When I took a penciling class, I asked the professor, “Can I pencil pages from this script I wrote for another class?” The same in an inking class: “Can I ink the pages I already penciled?” I wound up at the end of my degree with three-quarters of what would become Farewell, Georgia. And after I graduated in 2000, while my then-wife Katherine and I were milling around trying to figure out what we’re going to do, I finished up Farewell, Georgia’s fourth story. Now I had a project to send off to various publishers. Farewell was published in 2003…which sounds like a long time, but in publishing, it usually takes at least two years to get a book out after you’ve submitted it.

Winston-Salem and Midnight Sun

After you graduated, you relocated to Winston-Salem. Why Winston-Salem?

I would have liked to have stayed in Savannah. I liked Savannah a lot. Katherine wanted to move, so we made a list of cities that we liked, and decided that when one of us gets a job in one of these cities, we’ll move there. All the spots on our list were mid-sized Southeast cities: Winston-Salem, Athens, Roanoke, Nashville, cities of that ilk.

Then I got a job in Winston-Salem. North Carolina has a Governor’s School for gifted rising high school seniors, and I got a gig teaching Art at Governor’s School West in Winston-Salem, on the campus of Salem College.

You did a funny mini-comic about your Governor’s School class’ obsession with MODOK.

Right—that was also about Jason Lutes’ visit to our class. Jason was living in Asheville, where there was briefly a comics scene. Other people in Asheville at the time included Brian Lee O’Malley and Hope Larson.

That’s why I wound up in Winston-Salem. I knew Winston from band touring, and I’d seen some bands there too. Winston-Salem has an interesting musical history: that’s where Mitch Easter is from, and R.E.M.’s first records were recorded at Drive-In Studios.

I still like Winston-Salem a lot. Now that I live in Columbus, I don’t think I would really want to move back to a smaller place—I’ve gotten used to the amenities you get in a larger city. But I do feel that Winston-Salem punches above its weight class with artsy-fartsy stuff, like the A/perture independent movie theater and a good art scene for a small city. It wasn’t a bad place to wind up. Not much going on there, comics-wise, but I tried to improve that.

You were trying to start a comics community in Winston-Salem, and we met when you hosted the Camel City Cartoonists’ Guild and Social Club.

That’s a very unwieldy name. [Laughter.] As you know, there are cities that have comic “scenes,” like Seattle and Chicago, where artists frequently get together for “drink-n-draws,” group drawing sessions. Athens, Georgia was a regional example: a lot of SCAD graduates ended up in Athens, where they got mixed up with folks like Patrick Dean and Robert Newsome (who did The Journal of Modok Studies) and built a scene. So I thought, “Man, this is cool. I wish I had this.” There were a few people in Winston-Salem who were interested in comics, some of whom came to the Camel City Club to draw together, and some of whom I remain in touch with…

I’m Facebook friends with Alton Rumsfeld. He posts images of his beautiful paintings.

That’s great. I haven’t talked to him in forever, but Mandy Marxen and I still talk on Twitter sometimes. And I saw Adam Casey once in a while when I still lived in Winston. So the Camel City Club was my attempt to make a scene in Winston, and we had a decent run of monthly meetings held at the Sawtooth School for Visual Art, where I was also teaching comics classes.

I couldn’t come every month because the kids were so young, but it was a nice way to spend a Saturday when I could. I’d also stop at all of Winston-Salem’s comic shops. And while you were trying to build a scene in Winston, you were beginning work on Midnight Sun.

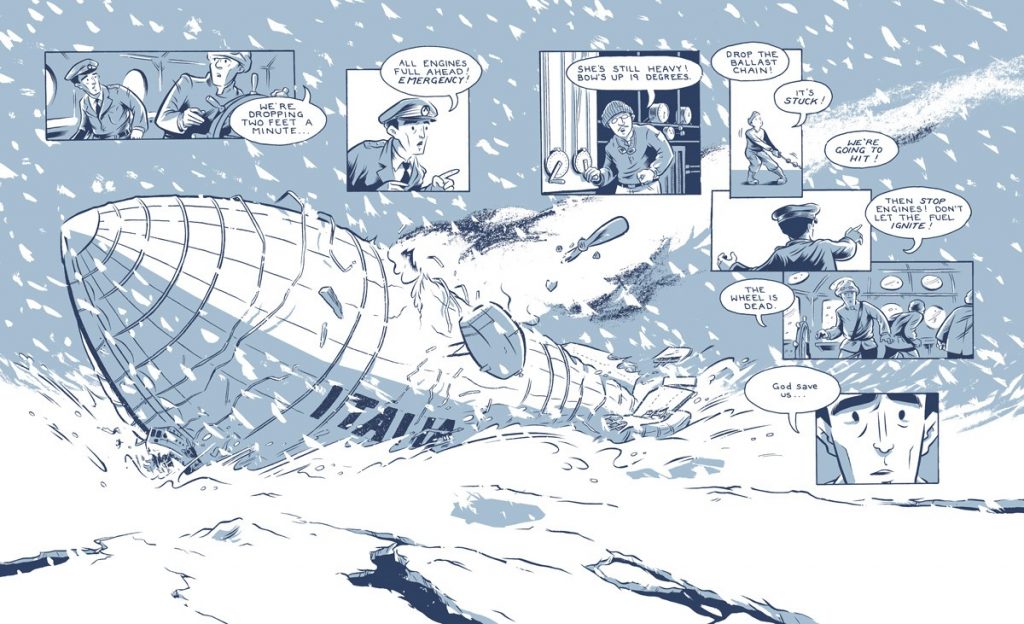

I guess it was that long ago. It’s getting bollixed up in my brain, because I actually started Midnight Sun before Farewell, Georgia.

You’ve said that your inspiration for doing a story set in the Arctic was that you wouldn’t have to draw buildings. [Laughter.] You also mentioned Jacques Tardi as an influence.

Some of it was Tardi, another guy that James got me interested in. I loved Tardi’s gray, faux-Craftint look. But yeah, I started working on Midnight Sun when I was at SCAD, and I still have a dummy of that early version—that I completely scrapped. If I went through the dummy, I could probably find a few panels that I used in the published version of Sun, but I put together the first issue at SCAD, telling the story in chronological order, and it wasn’t what I wanted. The published book has been rearranged à la Pulp Fiction, so that the zeppelin crash that incites the whole story doesn’t actually occur in the book until the very end. But that first version was in chronological order.

I actually pitched that dummy version to Terry Nantier at NBM, who visited SCAD on one of the school’s “Editors’ Days.” He was realistic with me, but at the time, he hit me as very gruff and abrasive. He said, “If you want to do this, are you willing to do a hundred pages of artwork for a $2000 advance? Can you conceive of a project and actually complete it?” At the time, I thought he was a big old jerk [Laughs], but now I realize that’s exactly what you should have said to a graduate student in comics. Don’t make any false promises. He wanted to make sure that some kid who’s doing his first comic can sit down and do the work. I think it was apt of Nantier to say to a kid still in school, “This is really swell, but are you actually gonna do it? Do you understand how much work is involved and how little money you’ll get for it?”

I didn’t abandon Midnight Sun because of what Nantier said—sometimes it takes years, but when I start a book, I finish it [Laughs]—but I did pick it up after Farewell, Georgia came out and I was living in Winston-Salem. As you know, Sun started coming out as individual issues, which was a terrible decision. [Laughter.] I don’t know why I did that.

Well, because you wanted some money coming in as you were doing the book.

I don’t know if you know this, Craig, but there’s not a whole lot of money in comics books! [Laughter.]

I said some money, not a lot of money!

Honestly, I think I serialized the book more to give myself a manageable chunk of work, to set a deadline of 24 pages every six months. That’s a bad reason to cut up a story…and proved to be a bad reason, because the Midnight Sun comic book was canceled.

You were following the Farewell, Georgia model: every time you finished one of the Farewell’s short stories, you felt a little catharsis. Ditto for Midnight Sun issues.

Yeah, but the cancellation was painful. Midnight Sun was published by Slave Labor Graphics, and I remember getting an e-mail from Dan Vado, who ran and still runs SLG: “I hate to do this, but we can’t finish the five-issue series.” Only the first three issues (out of six) were published. Even with indie comics, there’s a certain baseline number below which you’re taking a loss, and at the time that number was about 1500 issues. If you fell below that floor, then it’s costing the publisher more to print and distribute than they’re bringing in. So that’s why SLG abandoned individual issues.

Midnight Sun eventually came out as a completed book. In retrospect, I don’t know why I went with individual issues. It didn’t look good as a traditional comic book, which wasn’t the right trim size. When I was showing the early version of Farewell, Georgia to Ted Stearn at SCAD, he noticed that every page followed a nine-panel grid. Not that there’s nine panels on every page, but based on that grid. I wasn’t emulating Watchmen—that’s just a classic way to set up a comics page. I did that because it made me focus on storytelling rather than worrying about complicated page stuff. But Ted pointed out that there were places where I was struggling with compositions because of the constraints of the nine-panel grid: if you do a straight nine-panel grid, for example, you wind up with very tall, skinny panels. Taller and skinnier than, say, a portrait of George Washington, an awkward shape. And Ted said, “You should change your panel shapes.” And I was like, you can’t do that! [Laughter.] But Ted told me to do a different page shape—format should obey the content, not the other way around. And I thought, of course.

So I changed the shape of my pages for Midnight Sun: those pages are slightly squarer, and the book collection is squarer and smaller than the individual issues were. The Midnight Sun comic books were the size of a normal comic book, but because the original art was square, there was a lot of white space at the top and bottom of every page—which I wasn’t a big fan of. But SLG insisted on the comic book size because retailers will lose their damn minds if they can’t shelf a comic easily. If it’s not the same size as a regular comic, they will lose their damn minds. Thankfully, that’s not the case anymore.

Basically, the SLG people, either Dan or Jennifer de Guzman, said, “Just deal with the typical comic book format at first, and then when we publish it as a collected book, we’ll do it in whatever format you want.” And I was learning about how to negotiate with a publisher, so I agreed. And when the Midnight Sun book came out, it was very small. Most of my old stuff I’m content to have vanished because it looks ugly and the art isn’t very good…

I don’t think that’s true.

Well, you haven’t seen all of my old work. [Laughs.] But I think Midnight Sun still looks pretty good. I was in talks with Oni at one point to maybe reprint it in color or with a blue spot color rather than its original gray. And make the book bigger. It’s too small right now. And print it on something other than junky newsprint that doesn’t hold up. At some point I may figure out a way to get Midnight Sun out again.

Amelia Earhart

In 2010, you collaborated with Sarah Stewart Taylor on Amelia Earhart: This Broad Ocean, as part of a series of cartoon biographies sponsored by The Center for Cartoon Studies.

That was a series of books that James Sturm had sold to Hyperion. Literary agent Judy Hansen brokered that deal, and CCS was the books’ packager. I think it was a four or five book deal, and when I came aboard, two were already done, James’ and Rich Tomasso’s Satchel Paige book [2007] and Jason Lutes and Nick Bertozzi’s Houdini the Handcuff King [2008]. I was third, and then came John Porcellino on Henry David Thoreau and Joe Lambert on Annie Sullivan and Helen Keller. And the series has recently been resurrected, with a book on the Brontë sisters by Glynnis Fawkes.

That’s an impressive book series.

I think they’re very good. Almost all of them came out before the kid’s comics’ insanity that we’re currently in—this was all pre-Smile, pre-Dog Man, all those best-selling books. So I don’t think that they found the audience they deserve. And now they’re back in print, and there’s an interesting story behind that: according to the publication agreement, if the books went out of print with Disney or Hyperion, the rights reverted back to CCS. So CCS was on the verge of selling them to be reissued by another publisher, but Hyperion had right of first refusal along those lines. And Hyperion decided, “These are actually pretty good,” and reissued them all.

The Earhart book and all the rest were reprinted and I was very glad. I like to have stuff in print, and I got a little bit of money. Also, there were some issues with the first printing that I was able to resolve. I always hated the original cover, and made a jerk of myself to James, letting him know that I always wanted to re-do it.

A comparison of the first Amelia Earhart cover–penciled by Jason Lutes and inked by Towle–and the second edition cover (2020) penciled and inked by Towle.

I don’t think it’s a bad cover for the first edition. That’s the one I have.

It’s not actually a drawing by me; it’s a Jason Lutes drawing inked by me. You’ll note that it doesn’t look anything like the character of Amelia Earhart as drawn in the book. In fact, that came up at one of the first author events, up in Vermont: someone asked me, “Why does the character on the cover not look like the character inside?” Grrrr. I had gotten into a bit of a conflict with the editor at the time, and I was picking my battles. I was a hired gun, and while I let it be known that I didn’t like the drawing on the cover, I couldn’t do anything about it.

Amelia Earhart is a beautiful woman, but not traditionally beautiful: she has a horsey face, a long, thin face, and that’s the way I designed and drew her. And it seemed to me that the editor wanted a prettier version of her on the cover, which rubbed me the wrong way. I wanted my own drawing on the cover.

But I got a good paycheck for the book, and the editor of the series is ultimately the boss. But I was grateful to re-do the cover, with my version of the character. And I also got to fix something technical: the color trapping, which is where you print something with black line art and another color underneath it; if you know what you’re doing—and I didn’t at the time—you know you should fill in color underneath where the black ink comes down, because black ink printed on a white page looks different than black ink printed over a colored white page.

You see that in old comic books, where the black looks like different colors, depending on what color it’s gone over. So you look at the first edition of that original run of that Amelia Earhart book, you could tell the colors of traps: the blacks are kind of splotchy-looking. So I said, “We need to fix this,” and the people in charge at Hyperion said, “Well, we don’t really have a budget for that,” because it’s a bear of a job. And I volunteered to do it for free because it needs to look better. It’s been bugging me for 15 years. I will take a week to do that. Just let me do it. [Laughter.]

I’ve always liked that series of books because James and the Hyperion editor decided not to do conventional biographies. They don’t try to cover the subject’s entire life. They instead focus on specific incidents presented in a dramatic fashion.

James’ vision for that project was very much not the Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story kind of deal. [Laughter.]

Not the “so-and-so was born,” chronological approach to biography.

James understands how important it is to structure a story where a character has to make a decision, whether it’s a fictional character or a real person. Drama comes when a character decides or acts under some sort of stress, but you don’t have to start with the moment they were born. Or end with the moment they die. You find an interesting event or decision or choice that the person had to make, and you structure the story around that as your Act 2 climax.

That leads to some powerful effects. Joe Lambert’s Annie Sullivan / Helen Keller book…

His is amazing. His is hands-down the best of those books.

…ends with Sullivan and Keller accused of plagiarism and publicly disgraced! What a sad, surprising event to focus on, given Keller’s contemporary status as an icon for overcoming adversity. I like all the CCS biographies, but that’s a real standout.

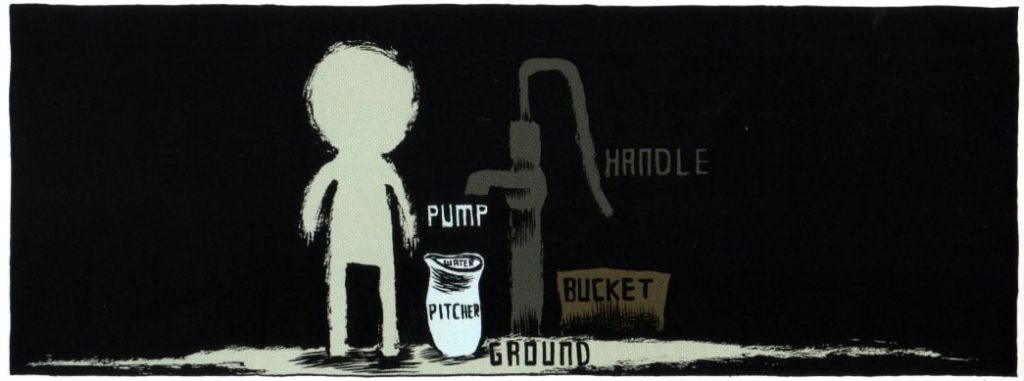

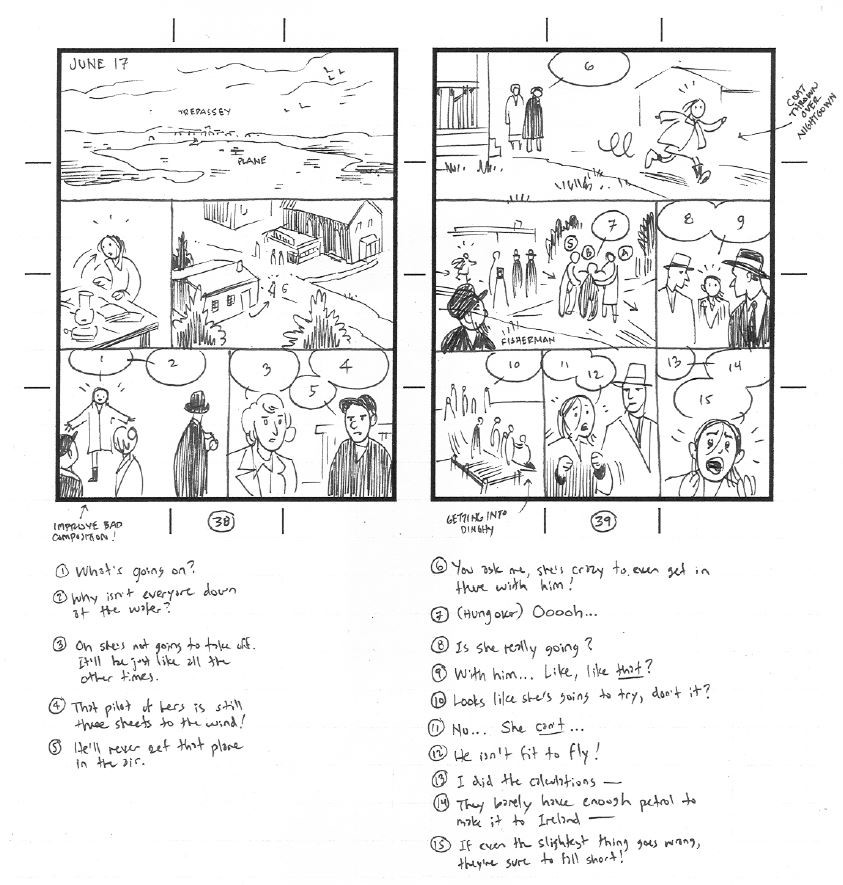

Absolutely. And I learned a lot from working in that series and doing the Amelia Earhart book—both about constructing a story and about visual storytelling. He’s not credited in a very transparent way, but Jason Lutes essentially thumbnailed all those CCS books, or at least he thumbnailed mine. I got a stick-figure version of each page from Jason. He actually did the storytelling. And that worked for me because I drew that book around the time my daughter was born, so I just did not have a brain cell free to tackle the storytelling. [Laughs.]

You’ve said before that doing the storyboards is the hardest part of composing a comic.

Conceptually, it’s the most demanding. It’s where most of the problem-solving takes place. And at that point in my life, I was not in a state to do any complex left-brain thinking, so it was nice to have Jason do those for me. I learned from them. There were situations where I was able to change images and suggest ideas. Jason’s thumbnails were all nine-panel grids, but a big suggestion I made was to use full bleeds to evoke flying and the expanse of the ocean. There’s not a full bleed in that book until Earhart gets in an airplane for the first time, and then we open up to a full-bleed two-page spread. Starting at that point, bleeds appear during moments of flying.

Oyster War and Size Matters

Next was Oyster War with Oni.

Oyster War was designed from the get-go to be in a Euro album format. I talked to an agent about Oyster War at one point, who said, “I could shop this around, but you would have to reformat the book to be paperback-sized, and three tiers per page instead of four tiers.” And I just thought, “No.” Stupidly.

I don’t think that’s stupid. Oyster War was a deliberate homage to the Tintin books. Again, you wanted the publication format to fit the content.

Yeah. If you’re an American fan of French comics, you know what happens when you take a book that’s supposed to be 9 x 12, translate it, and squeeze it into the size of a postage stamp. Like some of the reprintings of Christophe Blain’s comics.

Or Fantagraphics’ Joost Swarte’s book. When you see Swarte’s art printed big in Raw, it looks magnificent, but in that little Fantagraphics’ collection. It’s all squished up. The American edition of Epileptic is another example. That’s a book where the bigger the pictures, the larger the impact, which is why the American edition is less impactful.

I actually just picked up some of the original French volumes of Epileptic at a used bookstore in Seattle recently. And it is different. And that stuff just drives me nuts. The first decisions I make as a comics creator are about the size of my original art and the physical printed size of the book. Because when you figure that out, then you understand how big the lettering should be, to be legible. And you understand how much room you have in each panel for drawings. And you cannot arbitrarily change the size of the printed page on the fly, but it happens all the time in translated comics, like with those tiny reprintings of the Tintin albums.

Fantagraphics also did a Hate collection at one point, in black and white, Buddy Does Seattle, where they reprinted 15 issues. And the collection is smaller than the size of the original comics, and they just don’t read right.

You released Oyster War online first. How was that experience? How did it feel to put increments online and then collect it into a book?

As with Midnight Sun, I did that as a way to keep myself on a schedule, to make myself turn out a page on a regular schedule. I suggest that to students sometimes: put out a webcomic and commit to deadlines. My deadline was a page every two weeks, because my pages were huge and in full color. When you keep your deadlines, it’s a slow-but-steady way to create a book.

Oyster War was not well-designed to be online: my pages were in book format, portrait format, for a landscape screen. And I didn’t think about that. Nowadays you see people actually devote some thought to that. [Laughter.] If you look at Drew Weing’s Margo Maloo—one of my favorite webcomics—you’ll see that it’s obviously set up in a horizontal, landscape format, and the idea was that they could be stacked to a normal-shaped book. Thankfully, the publisher was willing to do horizontal Margo Maloo books. A lot of people draw horizontal online pages. I’ve posted progress pages from In the Weeds, my new project, and they’re all set up so they can be divided in half. I had the idea—and I still might do this—that when I’m at the point where I’m inking the Weeds pages, each page can be put online, broken in half, and presented in landscape format.

Oyster War got some buzz: didn’t one of the comic-strip syndicates carry Oyster War on their website?

Yes, GoComics did, which is a division of Andrews McMeel Universal. John Glynn, one of the editors, was a fan. They ran it just because they liked it. I got $100 once in a while from them, but it was not a big moneymaker. In order for that model to work, you need a daily strip that builds a readership. The only way that the online model makes money for both a cartoonist and for a site like GoComics is if there’s eyeballs on a new strip every day. And obviously, if I’m putting a page out every two weeks, that doesn’t really work. They ran Oyster War, and sent me whatever minimum payment you’re supposed to get, because they liked it.

It also turned up in some yearly “Best-Of” lists in The Comics Journal.

It also got an Eisner nomination for “Best Publication for Teens” in 2016.

You’ve been nominated for an Eisner four times and have yet to win: you’re still the Susan Lucci of comics. [Laughter.] Sorry: I’m making a joke and you’re dying inside.

It’s a cliché, but it is an honor to be nominated.

Teaching Comics

The biggest change in your life since the publication of Oyster War was your move from Winston-Salem to take a faculty position at the Columbus College of Art and Design. How do you like Columbus? You mentioned that you’d gotten used to the amenities of a big city…

I really like Columbus. There are cultural differences between the Midwest and the South, where I’ve lived most of my life, but I love the fact that Columbus is a bigger city…though hilariously most people outside of Ohio don’t realize that. They think you’re in some cowtown, even though Columbus is the fourteenth biggest city in the U.S. And I think it’s the second-biggest Midwest city, after Chicago.

Columbus has a big international community, great food, and amazing international grocery stores—and because it’s a college town, you get a lot of cultural and musical events. And obviously, the comics culture is incredible. There are only a few cities in the U.S. that have concentrations of cartoonists, but even those don’t have the institutional support for comics as an art form that Columbus has: CCAD (where I teach) has a Comics and Narrative Practice major, and the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum is the biggest collection of original comics art in the world. We’ve got Cartoon Crossroads Columbus, and Ohio State—pardon me, The Ohio State [laughs]—has comics classes and scholars like Jared Gardner there. The Thurber House, the Columbus Museum of Art’s residency…it’s amazing.

Ron Wimberly rolls into town, Frank Santoro visits the Billy Ireland to do research, M.S. Harkness moved here not too long ago, and Melanie Gillman just moved here too. A big cartooning crowd. And there just weren’t a lot of comics people in Winston.

No comics-central institutions in Winston-Salem, except for what you tried to start.

All that Ohio cartooning history is here too: Billy Ireland, Milton Caniff, Noel Sickles…and Jeff Smith is the grandfather of all this infrastructure.

Describe some of the classes you teach at CCAD.

I don’t teach in the Comics department per se. Comics hasn’t fully broken away from the Illustration department; we have a single chair, but they’re separate classes. I teach general illustration classes, though I think the website lists me as “Illustration, Comics & Narrative Practice.” There’s crossover. I don’t teach any classes in Comics proper, but I serve on thesis defenses, and I’m doing an independent study right now with a comics major on memoir comics. But I teach mostly Character and Environment Design, Drawing for Entertainment Design—a bizarre title, but it’s basically a “drawing boot camp”—and I teach Perspective, which is a class I really love. I have a weird perspective fixation; I collect old perspective textbooks.

That fits with your belief that visual arts educators should teach practical skills to students.

Yes, practical skills. Those are the three main classes I teach. We started a new class last term, Color Theory and Pre-Press, which was interesting to teach—though the first time you teach a class, you’re scrambling, you’re desperately trying to stay five minutes ahead of the students.

The current generation is very much about screens: everything’s digital, everything goes online. But there’s a huge difference between doing work in color that’s only going to be seen on a screen versus having it printed out on a physical sheet of paper. I thought that most of the students would be mostly interested in Color Theory because it would provide practical information on how to choose color palettes. I didn’t think they’d care about how printing presses work, what CMYK printing is, and about ink density levels. But from reading my course evaluations, it’s the other way around: they’re into printing. Maybe that’s because I arranged for the class to take a trip to a local commercial printer, and they saw a big CMYK press and die-cutting.

This class coincided with the release of Four-Fisted Tales, so I was able to show them my original file for the book’s cover. Then I had them pull up the cover on their phones, on their laptops, on the printed book—and I also showed off a banner I had made for conventions, and postcards I printed on a laser printer. It all looks different. It demonstrates that if you want an image to look a certain way, you have to understand that physical printing is different from what you see on a screen. If you want image control, you have to grab a Pantone swatch book, and tell the printers, “That’s the color I want.” It turned out to be a fun class. But the classes I usually teach are about nuts-and-bolts illustration skills.

Animals at War

You brought up Four-Fisted Tales; let’s talk about your newest book, published in the summer of 2021. Why a book about animals in combat?

Like a lot of writers, when I find something interesting, I note it down. I have a Word document where I write ideas—and at some point, I stumbled across a Wikipedia page that lists animals that have been used in combat situations. And I thought, “That’s kind of interesting…”

Specific names of animals? In your book, you talk about “carrier pigeons” as a group of animals, but you also talk about individual cats and dogs.

I think the Wikipedia page names specific animals. I bookmarked that.

That’s where you found out about “Tiddles” right? [Laughter.]

Maybe I found out about Tiddles later. My first thought was that this topic would make a great multi-artist anthology. At one point, I even pitched it to a publisher, and it got fairly far along in the process, but I couldn’t get enough money out of them to pay people a decent page rate. I’ll do my own books for chump change, but I won’t edit an anthology if I can’t pay people a wage that I feel comfortable with. I’m not going to tell someone, “You get 50 bucks a page.”

So that fizzled, and I started the book I’m still working on now, In the Weeds.

Which we’ll get to in a minute…

…and later, I saw on The Comics Beat a news item about a new comics imprint called Dead Reckoning, a division of a prose publisher, and they were specializing in historical and military topics. I found the email address of Dead Reckoning’s editor and pitched it to him.

How was working with Dead Reckoning on the book?

The process of working with the comics part of the system was very easy and carefree. Gary Thompson, who heads Dead Reckoning, knows comics culture and how comics work. But after that, I wound up in the system for the overall publisher, and—although I won’t grouse because the experience was overall very positive and I’m very proud of the book—there were situations where I could tell I was out of the comics-centric editorial system and I was dealing with people more used to prose. They’ve been in prose for decades, and this comics stuff is new for them. Editing a comic is different than dealing with a prose book, and I will be completely 100-percent up front that I can be a huge pain in the ass because I’m particular about how my art looks. I don’t want to be a jerk just to be a jerk, but there are situations where I stood up and said, “I want this to look different.” With the Amelia Earhart book, we talked about how I didn’t go to bat for the cover, and then for ten years it had this cover I didn’t like!

In an interview, Dan Clowes talked about obsessively going back and fixing a panel that he’d already spent ten hours drawing because taking another three hours to do the fix was better than spending the next twenty years of his life looking at a shitty panel that could’ve been better.

I asserted myself with certain issues with Dead Reckoning. There were other issues that, if I were king of the world, I would’ve tried to change, but when you work with a publisher, you have to pick your battles. I made a distinction between the things I really wanted to address, and other things that I could live with. There’s never been a publishing situation I’ve had—maybe other than with Oni!—where there hasn’t been some kind of back-and-forth. That’s part of how it works.

You and the publisher both want to sell the book: you both have the same goal, but sometimes you have different ideas about what would best serve that goal.

You said that you found the list of animals at war on Wikipedia, but your research goes much deeper than that. Talk more about the research you did. Let me ask a specific question: when did you find out that slugs were sensitive to mustard gas? [Laughter.]

I can’t remember, but doing research is a little like confirmation bias. Once you open up your brain to register when there’s overlap between animals and military conflict, you suddenly notice this stuff everywhere. It’s like those people who think there are mystical numbers that occur over and over again: the number 42 keeps turning up because you’re looking for 42! I set up a bookmark folder, and while I was putting my book pitch together, anytime I would see something relevant, I would bookmark it.

There were certainly things I stumbled on once the book was in progress too. I also bought some books and got some books from the library and compiled examples. And those books had bibliographies, so I tracked down that material. At this point, I couldn’t tell you where I found all the examples in Four-Fisted Tales, but I made sure that for every story in the book, I had at least two different accounts—even just for copyright reasons, so I wasn’t just lifting an existing story wholesale. And you have to verify that they’re actually true. [Laughter.] I found one or two that were great, one in particular about a ship’s cat who was “cursed” because the cat jumped from ship to ship and every time the new ship would be blown to bits. [Laughter] But I couldn’t find two sources to back this story up. I tried to contact the author of the original story, but they never responded, and I thought, “I bet this is probably bullshit.” [Laughs.]

I’m pretty active on Twitter, and when I told everyone I was working on this book, anytime there’d be some story about rats finding landmines, it was “CC: Ben Towle.”

You posted on Twitter about that recently, when one of the land-mine sniffing rats passed away.

Right, Magawa the rat hero.

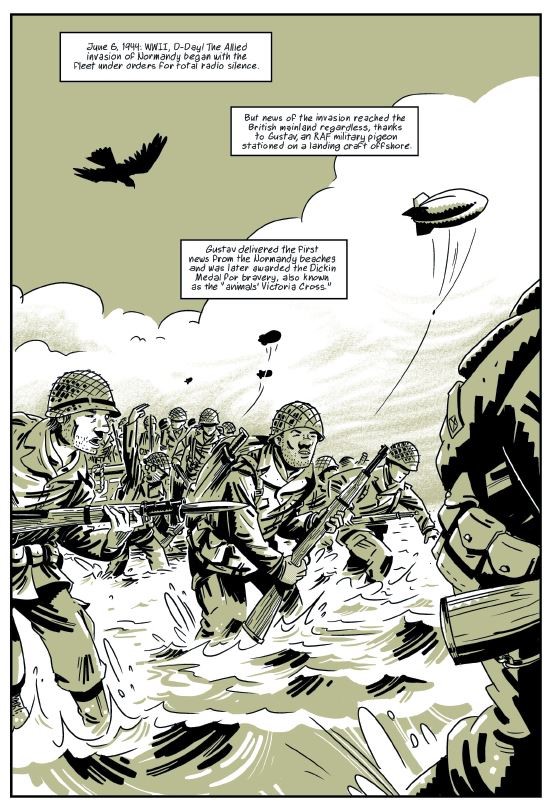

Your art in Four-Fisted Tales is great, the best of your career. The chapter on carrier pigeons, for example, is all full-page splashes, really striking images.

Thanks. There are a few wonky things that I’d like to fix, but that’s probably true of every book.

And you’ll be obsessed with them for the next ten years. [Laughter.]

I still can’t draw a goddamn bear to save my soul. In one of the last panels in the story about Wojtek the bear, when the soldier hugs the bear, I thought, “Finally! A bear drawing that works!” [Laughter.] The rest of my bears look pretty bad. Passable, but…

I thought the bear action figure on the last page looked pretty good.

I’m very happy with the art in most of Four-Fisted Tales. I tried to loosen up a little bit. If you look at my pre-Oyster War stuff, you see it was all ‘90s feathering, Dan Clowes-y brushwork. Not that my work looks like Clowes, but in the actual technical tools I used…

And in the amount of lines you put down. But in Four-Fisted Tales, your human figures are simplified, particularly the faces, but the backgrounds are detailed, showing your historical research: the right kind of tanks at the Somme, etc.

I need to tone that down too. I saw a Hugo Pratt show in Lyon, France at one point—I love Pratt, and when you look at printed Corto Maltese art, you’re like, “Oh my God, every line is so expressive. Every line’s important.” And then you look at the originals, and you realize he’s flying through this shit. He’s a guy with a deadline. The artboards have tape stuck to them, some of the drawing is in felt-tip pen, some in Bic pen…

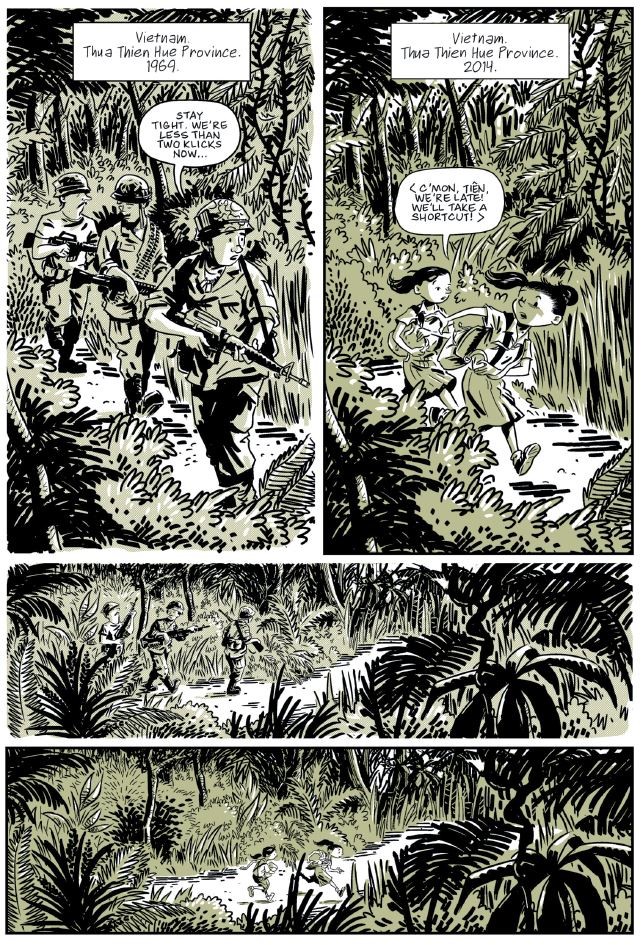

I tried to take a little inspiration from Pratt. In fact, in Four-Fisted Tales, I re-did one story, the one with the dog named Satan running through No-Man’s Land. I drew that story for the pitch I sent to Dead Reckoning, and I originally inked it in that brushy style that looks like Midnight Sun and the Amelia Earhart book. I wound up scrapping and re-inking it, and I did the whole book with just two pens: one a big, square, blocky pen, and another that’s basically a Micron. No brushy style in there. If you look at that one story that takes place in Vietnam, I took this almost-Prattesque approach, not that I’m on that kind of level.

When I said that your backgrounds looked complex, that was one of the stories I was thinking of. You’ve drawn some dense jungles and vegetation…

They’re dense, but they’re not highly rendered. I still tend to render out buildings and rooms. I’d like to loosen up with architecture a little bit, but loosening up is really hard for me. Some artists can do it. Richard Thompson: his pencils look like my thumbnails. He’d attack the page with an ink pen and come up with a finished picture. I’ve tried that, and it looks like a three-year-old drew it.

I see Ralph Steadman in Thompson, and Steadman just splatters the ink.

I think Thompson essentially drew directly in ink. I do tight, labored pencils, and I wish I could figure out how to loosen up. A lot of the French cartoonists I like are very loose. Look at Christophe Blain’s work: what little I’ve seen of his pencils, they’re not detailed. Most of his mark-making is in direct ink.

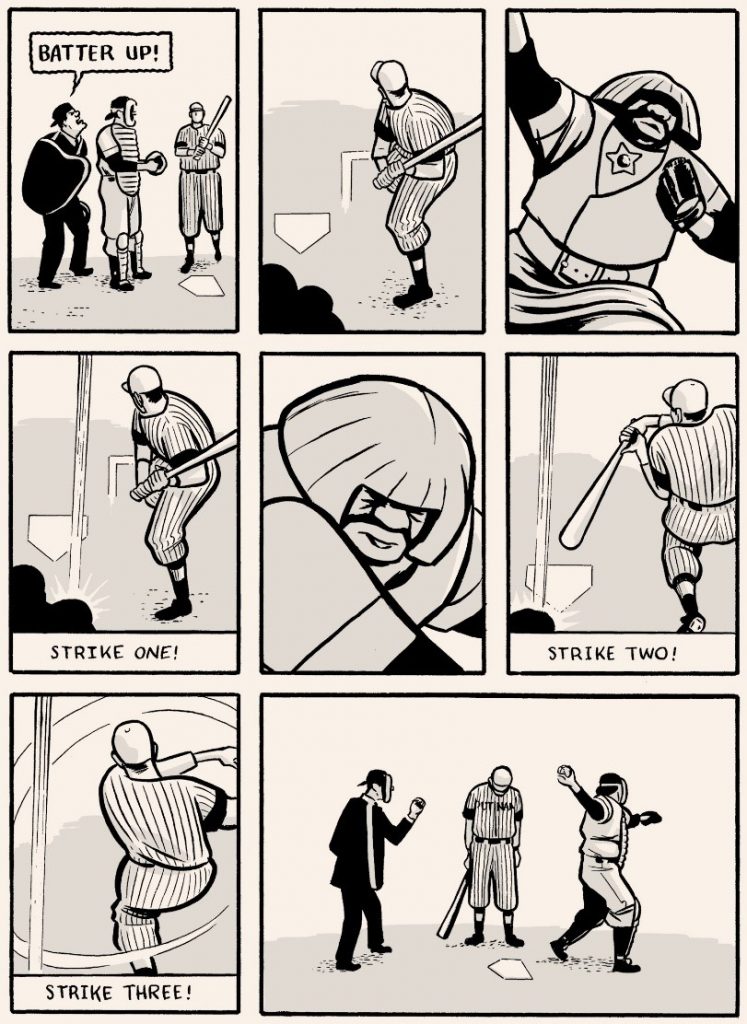

Another thing I liked about Four-Fisted Tales was the fact that for each chapter you chose a different formal construction. For example: the entire chapter about Wojtek the bear is based on the famous “silent” issue of the G.I. Joe comic book [G.I. Joe #21, 1984].

That whole chapter is a wordless homage to that G.I. Joe story called “Silent Interlude.” The one with the Klaus Janson cover. I read that book when I was a kid—I wasn’t a big G.I. Joe person, but I read this particular comic over and over. There was something about the wordlessness that was compelling.

Drawing non-fiction stories runs the risk of creating what Tom Spurgeon once referred to as “Wikipedia Comics.” [Laughter.] Basically: you say what something is, and you illustrate it, which can get boring. So I tried to come up with formal challenges to differentiate each chapter from the others. I decided to do the Wojtek chapter without words—and I thought, “What if I also based each page on G.I Joe #21?” Both in the sense that the panel grid is the same, but also that the compositions of each panel are the same: there’s an object in the foreground, swapping out Cobra Commander for a bear, or whatever. Put them side-by-side, and you can see the similarities.

I wonder if I should’ve mentioned that in the book…it’s a subtle borrowing.

A comparison of the layouts of a page from G.I. Joe #24 (1984) and the Wojtek story from Four-Fisted Tales.

There’s a tip of the hat at the end of the Wojtek chapter, with the G.I. Joe-inspired action figure labeled, “A Real Ursine Hero”…

But you have to be a G.I. Joe person to catch it. Yeah, the carried pigeon chapter is all splashes, there’s a story with pages that follow a two-two grid, the Vietnam story has two parallel plotlines in two different time periods, there’s one about dolphins set up as a courtroom drama…trying to come up with some kind of a formal constraint for each chapter makes it interesting for me, and for people who read it. That’s a by-product of my comics schooling; when I went to SCAD and hung out with James Sturm, Oubapo was in the air—people would play Five-Card Nancy, do Narrative Corpse exercises, and make a group comic with the Shuffleupagus. We did some of those exercises at the Camel City Cartoonists’ Guild and Social Club.

I took an Oubapo workshop at SPX around then—I think Matt Madden ran the session.

It’s kinda cornball, but constraints give rise to creativity. When I have a formal constraint to work with, when I start problem solving, it’s easier for me to get something on the page.

I initially thought that maybe you were inspired by a story in Kurtzman’s Two-Fisted Tales #26, which focuses on a dog present at Korea’s battle of the Changjin Reservoir.

I haven’t read that. Given that my book is called Four-Fisted Tales, it might be surprising that I’ve read the handful of Kurtzman-drawn war stories, but only a small scattering of the rest of them. I’ve read the Toth one, of course—“F-86 Sabre Jet!”—with the pilot in silhouette for several pages, like the old John Byrne “Snowblind” trick.

Drawing What You Want

You’ve been posting pencils on Twitter for your next project, titled In the Weeds. What are you willing to spoil about Weeds in this interview? I know that it’s based on your own life…