I Never Promised You a Rose Garden has the feel of an illustrated séance, a ceremony in which genderqueer cartoonist/medium Mannie Murphy channels the many ghosts that haunt their hometown of Portland, Oregon. And they are restless ghosts, born of racism, violence, and tragedy.

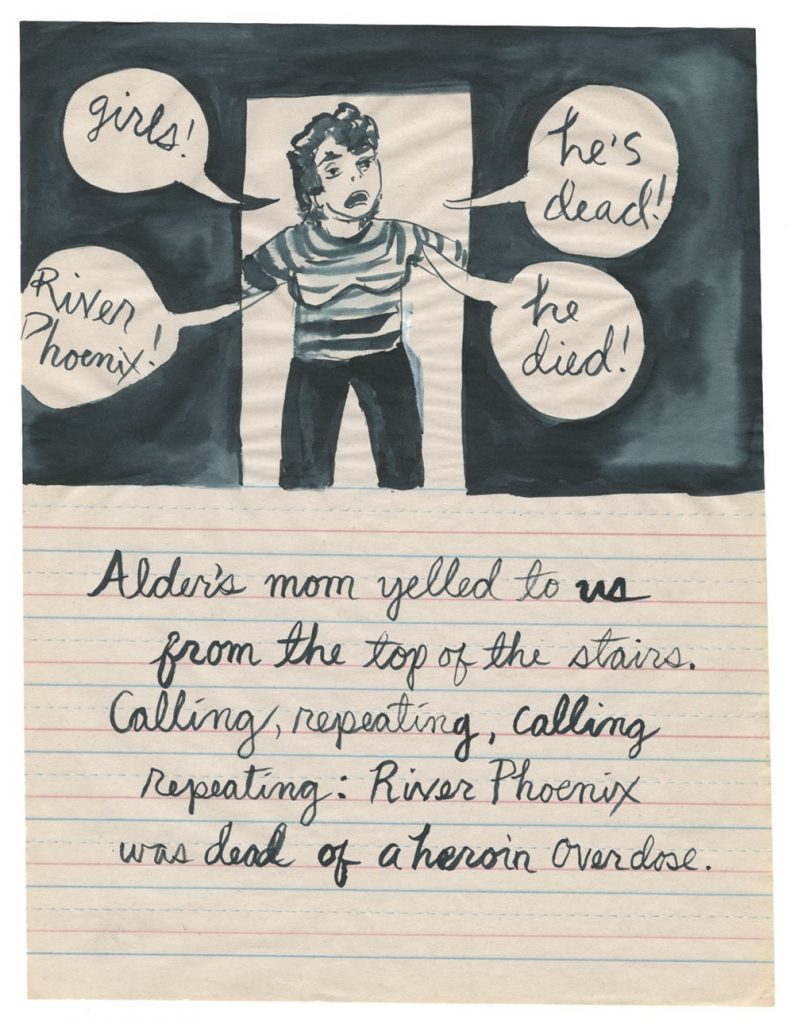

Murphy’s winding narrative, illustrated in moody ink-wash drawings, takes as its springboard the premature death of celebrated Oregon native River Phoenix and spins from that themes and variations of loss and corrupted innocence, largely stemming from the state of Oregon’s racist origins and their toxic present-day reverberations. Digging deeply, Murphy reveals long-hidden truths. Though Rose Garden is lightened by their affectionate autobiographical asides, it is an ugly story.

It’s also necessary—and its publication, in the George Floyd era, couldn’t be timelier. The shameful history of Oregon is also the shameful history of the United States; acknowledging and exposing these events—no matter how uncomfortable—is a first step towards reconciliation, if not exorcising them all together, someday.

The book’s four chapters, with their seemingly disparate events, ultimately coalesce to form a tale of centuries-old pain. Chapter One, “My Own Private Portland,” briefly recaps the troubled life of Phoenix leading up to his death by accidental drug overdose on Halloween night,1993. In Chapter Two, “Ken Death is Dead,” Murphy reveals more of Phoenix’s backstory as well as those of his contemporaries, particularly Ken “Death” Mieske, a violent young white supremacist. In Chapter Three, “The Flood,” Murphy travels back to the mid-1800s and the unsavory origins of Oregon, including the colonial genocide of Indigenous tribes and the ongoing terrorization of Black communities. In the final chapter “Victims of Groupthink,” Murphy brings their narrative back full circle, returning to one of the book’s central themes: the exploitation of lost, confused youth by misguided or downright malevolent adults, inevitably leading to disaster—with the kids as collateral damage.

As the lynchpin of Murphy’s narrative, Phoenix is a wounded angel, the ultimate Beautiful Loser. Like James Dean before him, Phoenix’s film career was brief but almost instantly legendary due to his extraordinarily empathic screen presence in films like Stand by Me (’86) and especially Gus Van Sant’s 1991 cult-classic My Own Private Idaho. Murphy confesses their instant devotion to him: “When I first saw Chris Chambers’ tearful campfire confession (from Stand By Me), I was done for.” In both of those roles, Phoenix projected heartrending vulnerability and seemed completely without artifice. But his real-life lack of guile often got Phoenix into trouble, leading to his ultimate downfall.

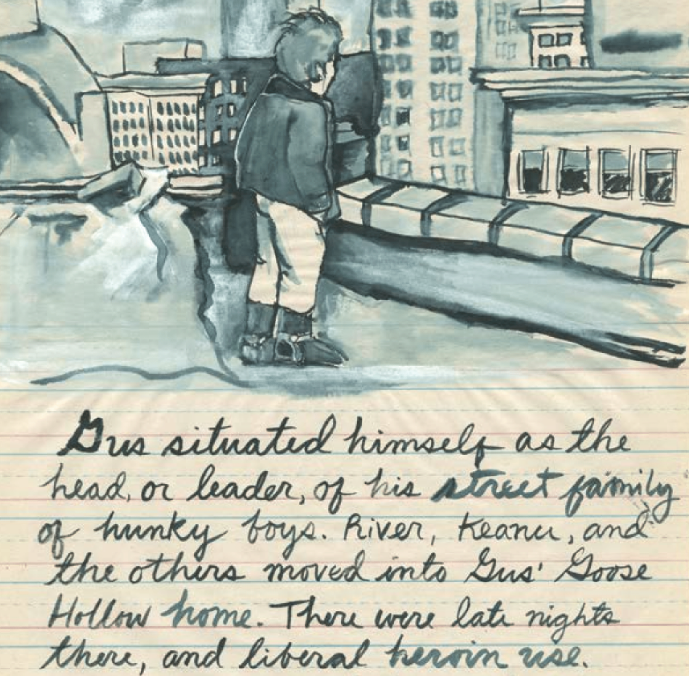

Murphy describes how Phoenix and his good pal Keanu Reeves connected up with acclaimed film director Gus Van Sant for My Own Private Idaho, then zeroes in on Van Sant’s attraction to Phoenix: “Gus fancied troubled boys. The ones with eyes older than their faces.” They also declare Van Sant’s racial sensitivity to be “sorely lacking,” as evidenced by films of his like Mala Noche, in which handsome Mexican males are fetishized by the white protagonist. This becomes an important point to recall as Murphy’s narrative then turns to discuss Ken “Death” Mieske, another troubled street boy.

Murphy presents Mieske as a sort of malevolent mirror image of Phoenix. While Phoenix’s troubles ultimately led him to self-destruct, Mieske, a neo-Nazi involved in Portland’s punk and deathrock scenes, directed violence outward. Murphy informs us that Mieske “Didn’t exactly go to my school but he hung out there a lot,” and editorializes that he was seen as “Cool, Lord help us.” Mieske was eventually kept by a wealthy gay man called Mr. X, who was “tight bros from way back” with Van Sant.

In 1988, Mieske and two of his friends beat an Ethiopian man named Mulugeta Seraw to death on the street. A few months before he murdered Seraw, Mieske was filmed by—you guessed it, Van Sant—for a short film called Ken Death Gets Out of Jail (apparently now locked away unseen in Van Sant’s possession). Throughout the discussion of Mieske, there is zero sense of any adults reaching out to him, trying to guide him in a better direction. His bad boy “cool” must have been far more beguiling.

The intel here about Van Sant brings up for me that age-old issue of whether one can or should separate the art from the artist. I make those gut decisions on a case-by-case basis and my gut tells me that I’ll never be able to watch another Van Sant film in quite the same way again. Though well-meaning in his self-absorbed way, he was, at the very least, exploitative and, at worst, predatory. And his romanticization of heroin use in his films (as “a blissful, sub-urban dream”), though an artistic choice, is ultimately a questionable one.

Murphy’s epilogue to Rose Garden, “Young Hatemongers,” finishes on a powerfully unsettling note as they recount a mini-riot that erupted on a 1988 episode of the live-audience talk show, Geraldo. The featured topic was white supremacy, with a bevy of supremacists as guests. It went badly, as the supremacists deliberately provoked violence. Rivera comes across as yet another adult exploiting youth for his own gain: “It made for great ratings,” Murphy deadpans.

Murphy, a longtime favorite cartoonist of mine, has self-published a few solo comics previously, including the Xeric Grant-published I Still Live, and they were also the editor-creator of the Ignatz-nominated anthology Gay Genius. Throughout their career, they have been dedicated to exploring queer history and have shown a keen interest in spiritualism and the occult (they also self-published a book called Symbology and successfully produced their own deck of Tarot cards). Their skillsets are fully on display in Rose Garden, placing historical facts within a deeply personal context. Their intense ties to Portland radiate throughout the book, even as we sense them recoiling from much of what they uncover.

Murphy’s ghostly green-gray drawings, each one a mini tone poem rendered on lined tablet paper, evoke the cool, foggy gray of the Pacific Northwest, along with a certain middle-school nostalgia. The flip side of each chapter’s title page illustration shows the wash soaked through, the drawing on the preceding page seen in reverse—like a stain—echoing their constant theme of dark events reverberating across time.

The overall book production is canny, playing to Murphy’s strengths: the pages are reproduced so that the wrinkles on the paper made by the wash are visible, lending the volume an earthy, homemade scrapbook-like feel—which to me is the absolute core of Murphy’s aesthetic—the antithesis of the slick digital comics stylings so prevalent today. Though they often display a downright naïve feel, whatever Murphy’s drawings may lack in anatomical correctness they more than make up for in soul and immediacy. Their handwritten cursive text feels utterly appropriate.

Rose Garden begins in heartbreak and pathos and concludes on a chilling, unhappy note, as Murphy reminds us that the evils of white supremacy and racism continue, often aided, directed, or carried out by people in positions of power (we all remember who killed George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and far too many more, right?). Murphy’s moving, mournful elegy for the dead of Portland, Oregon extends far beyond the state into seeming infinity, and that’s the biggest tragedy of all.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply