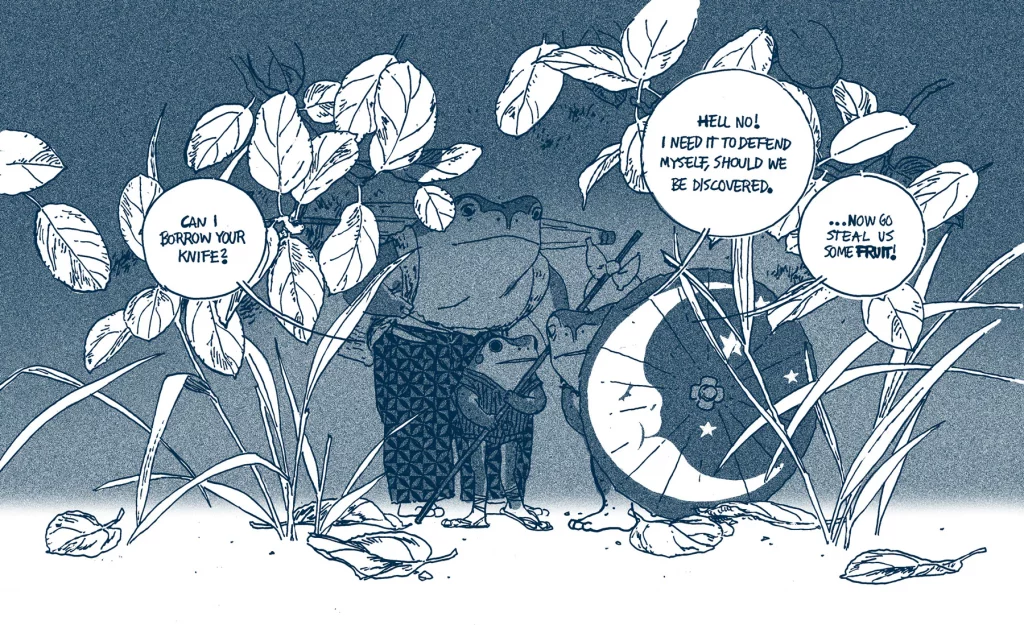

“Thinks the minor frog, running across the yard:

I did it! I did it! I committed a crime! But only a small one!”

-Our hero, after stealing a melon from a garden.

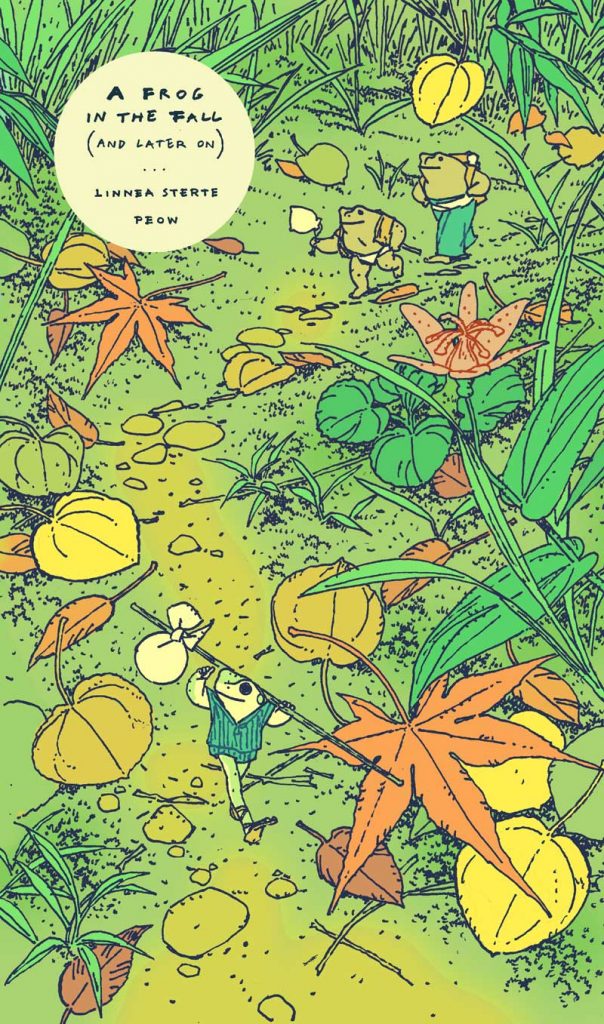

Reading A Frog in the Fall by Linnea Sterte was the most exciting comic experience I’ve had all year. In a breathtaking package full of gorgeous art, it tells a story that answers a resounding “yes” to the question “can a hero face only kindness and compassion instead of adversity, and still be a hero?”

We’ve asked a lot of questions of our literature through a meta-modernist lens (think post-postmodernism), such as: Can a story exist without conflict? Can we envision a future that is hopeful instead of hopeless, but still feel relatable? Can we drive a narrative through acts of kindness and sincerity instead of acts of betrayal and irony?

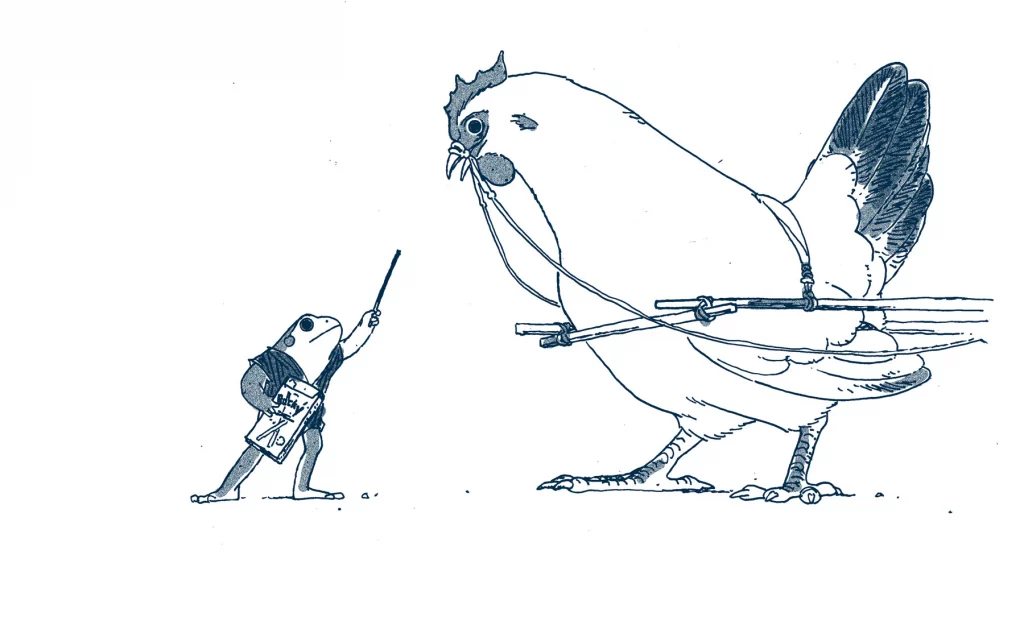

A Frog in the Fall sees our main character, Minor Frog, embark on a journey. Though not explicitly forbidden from leaving his home and apprenticeship under Great Frog, we see him leave safety and security for adventure with passing vagabonds. Minor Frog is naive, ill-equipped, vulnerable, but so excited to see and experience the world.

Both in plot and aesthetics, A Frog in the Fall is set up to be an animal parable; a classic furry fable. We know how these stories go. The Ant and the Grasshopper type stuff: They are cautionary tales in which a hero’s hubris leads them to tragedy, death, or debilitation. In these tales, our protagonist is served punishment for being lazy, naive, prideful, or simply not obeying authority or moral doctrine. The message is “You cannot trust outsiders,” “You cannot disobey your elders,” or “if you gamble on whether the world will be kind to you, you will always lose.”

But A Frog in the Fall subverts that message. It depicts a world in which our naive hero journeys into the ill-advised unknown in pursuit of experience and adventure, and everything turns out alright. He is met with kindness, he is offered favors, he is neither attacked nor demoralized, and he is not disciplined or chastised when he returns from his journey.

Minor Frog’s conflicts are internal. He worries that he will get in trouble for borrowing and possibly losing someone else’s belongings (and he does lose them.) He fears that the large dog following his group means to eat them. He distresses over whether Great Frog will be mad at him for leaving his home and his duties.

Relief

Even without conflict or danger, the story is deeply compelling and exciting. Minor Frog ventures “to the tropics,” along the way meeting all manner of characters who would normally portend doom, but instead…they simply do not. They give directions and advice, show off curiosities and spectacles, and even provide food and transportation. Upon reading, I almost felt like I was experiencing a reverse-thriller — at every turn I was clenched and ready for disaster or violence to befall our protagonist, but instead, my heart had to quickly reckon with a scare that wasn’t coming. I guess that’s called relief.

After running away, the first encounter Minor Frog has is with a cicada, wailing about his impending death. Normally this would stand as a warning, or as foreshadowing. One last signal to Minor Frog that it’s unwise to set out on a journey as winter approaches. Maybe he should turn back and prepare for the cold months with his mentor. But instead, Minor Frog asks the cicada for directions, and it kindly obliges, pointing him to the vagabond he’s trying to catch up with.

Later, the party meets an eerie Persimmon Tree Fairy, so lanky and oddly-shaped that she startles the group when she appears. She shares food with them, and gives them a place to sleep. But in the dead of night, and framed in darkness, she says “Little Frog? Want to see something terrifying?” Minor Frog follows, and while it seems like he is being led to sacrifice for the crime of trusting strangers, (he even remarks “It’s so quiet…”) it turns out that the Fairy just wants to show him that a large dog has been following his party. She is simply, and kindly, warning him. It was no mistake to trust her.

After partying with a friendly village of seaside cats and parting ways with his vagabond toad companions, Minor Frog turns around to head home. He confronts the dog in order to pass, prepared to kill it if it tries to eat him. Is this the final confrontation we’ve waited for? The dog, acting as an ominous specter by leaving footprints and carcasses on their care-free path, finally coming to collect the soul of our hero for the crime of stealing a melon from her garden in the second act? No! Yet again, not at all! The dog is perplexed at Minor Frog’s aggression, and says she was simply curious and followed them, taking an opportunity for a refreshing walk. Then she offers Minor Frog a ride home on her back.

When Minor Frog finally approaches home, he collapses in the snow, thinking he’s done for. He is without regrets, happy to have gone on a beautiful journey. Ah, here it is, we might think – the irony we were waiting for. To have met such good fortune for his whole adventure, only to die feet from his own warm doorstep! But no, again: a Plum Tree Fairy notices him and sends a mouse to retrieve him and bring him home.

Once home, he doesn’t even face consequences for abandoning his duties. Great Frog was simply fearful for his safety, and is glad to have him back. Minor Frog is still welcome to the security of the food stores even though he didn’t help prepare them. There is no punishment, local or cosmic, for wanting to go on an adventure and hoping everything would turn out okay.

Oh, we finally think. This is a story where nothing bad happens to our hero.

No conflict? No fights? No violence? Then why was my heart beating so fast?

Because it’s a good story.

Symbols

The autumn, as a symbol, usually represents an approaching hardship that needs to be prepared for. It’s the opposite of spring- hope, new life, signs of abundance to come. Autumn is the approaching dark, when death comes, when the cold sets in. A critical time in which you must be vigilant and strong.

This illuminates the subversive nature of the themes that are actually contained in the story even more clearly. All things point to danger, but Minor Frog finds only joy and kindness.

While this is a subversion of a cautionary fable and not a fairy tale, I can’t help but to compare A Frog in the Fall to other current graphic novels addressing the ways in which we can contemporize these genres today. Trung Le Nguyen’s “The Magic Fish” envisions our capacity to change the endings of the stories we tell to envision hope and to connect across generations. The short stories of Melanie Gillman’s “Other Ever Afters” imagine a shift in power, in which vulnerable people find peace and safety when their lenses shift to understanding instead of fear. They ask “What happens if, in the moment you expect to be hurt, you are not? What if this experience changes you and those around you for the better, instead of punishing you?” And they answer.

Towards the end of the book, the Minor Frog, riding home on the back of the dog he was sure was going to eat him, thinks, “How am I this lucky?”

I dwelled on this line for a while. Because the luck he speaks of means, on the surface “How am I so lucky to be able to experience the thrill of moving so fast on the back of a running dog?” But to the reader, it really means “How am I so lucky to have gotten through this entire narrative without facing doom?” How did he get so “lucky” this entire time, that every potential danger he met did not even attempt to harm him?

What if we framed the potential of our encounters with danger to result in our harm not as “luck” but as a result of every person we encountered actively choosing to help us and care for us? Is that such a bad world to imagine?

Physicality

I can’t talk about this book and not address the triumph of its construction. The book itself has a thick open glued spine with exposed stitching, sandwiched between two thick pieces of twice pantone-color printed chipboard. The cover colors, navy and white on warm gray, bridge the inside and outside with a muted-color anticipation of autumn- neutrals and darks, cold against warm.

That carries into the interior- digital printing in navy on sturdy eggshell paper with a risograph-like diffusion dither texture- it all serves the experience of the book: rustic, earthy, cooling. It’s beautiful. On top of that (literally) is a full-color slipcase. Snug with a soft-touch texture, it depicts the approaching autumn more verdantly- full of greens and browns, that again reinforce the experience of an approaching coolness when removed and facing the dulled colors of the interior book.

Single panel, full-bleed pages keep you immersed. Hand-written text (sometimes with cross-outs included) make the book feel like a diary, a journal of the adventure. The book is filled with texture, texture, texture, as you walk the earth as a little frog without sandals.

There is everything to say about Linea Sterte’s art. It’s detailed and clever, cartoon animals never looking so real, breathing on the page. The characters are fashionable, the landscapes lush and full. There are no corners cut, and you feel the love of drawing in every leaf and blade of grass and tiny amphibian toe. The tones are efficient and smart, doing many duties from adding depth to the frame, texture to clothes, and atmosphere to scene.

Both package and content are triumphs of the book.

How are we this lucky?

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply