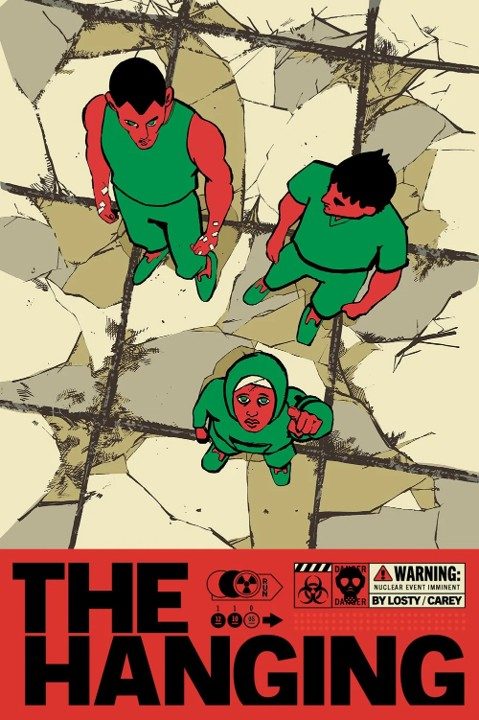

The Dystopia. Specifically, sub-section 2A (ask your local English Lit BA) – the “walled city under intense repression” type. It’s the one that does not bother to hide that everything has gone to shit. People are hungry, angry, and harangued. Public services constantly fail, if they even exist, except for the police — they work extra-hard to stomp out any possibility of resistance. 1984 is the classic example of this, but the field of comics is not lacking for choice: your Judge Dredd, your Night Hunters, your V for Vendetta, Night Zero, etc. And now there is a new member in this party1 – The Hanging; a short graphic novella by writer-artist Aaron Losty.

Losty is responsible for the fine youth drama Clearwater, a work that is categorized as a “crime story” but only in the loosest of terms. Like the early works of Ed Brubaker before he fell into repeating the same familiar patterns, or some of the more outré novels by Charles Willeford, it is safer to say that Clearwater exists on the periphery of crime, both as an occupation and a genre. Clearwater is all the better for it. There is much to be said for a genre piece that knows what it is, but also a lot to say against genre pieces that use genre conventions as a crutch or a prison for creativity. “Crime” is a fact of life in Clearwater, it is not a convention.

The Hanging, in turn, is a bit closer to a “familiar territory”, which makes it a slightly weaker story. The interesting element, that a series of nuclear bombs constantly hover above the heads of the walled city in which the story occurs, a Sword of Damocles literalized, is hardly touched upon within the plot itself. The world these bombs hover above could be one of a dozen or a hundred doomed cities, in dozens and hundreds of pieces of fiction. It changes the tone of the story, gives it a slight edge absent from many such tales, but doesn’t change the plot one bit.

Indeed, The Hanging isn’t about big events. It’s not about revolutionaries who try to bring down the system, or the wicked brutes that run it. It’s not “how did we get to this” nor a “what do we do after.” The Hanging is, mostly, a snapshot. We follow a small family unit, as the children are forced to find work in order to afford meager survival; only to encounter an abusive system intent upon extracting labor with as little reward as possible, roving gangs of robbers waiting to take what little the children earn, and a militarized police (or is it policized military?) looking for any excuse to break someone’s skull. It’s violent and grim and depressing and not particularly new. A well-trodden ground, if you will — like a boot stomping on a human face. Forever.

Still, “nothing new under the sun” is, by itself, not new. Most of the works I cited earlier didn’t invent the genre (even 1984 borrowed shamelessly from previous works). That The Hanging isn’t particularly revelatory in its world-building does not make it bad. It is, in fact, a very good version of this type of story, mostly based on Losty’s excellent artwork. Already a good cartoonist beforehand, a student in the schools of Miller and Breccia, Losty has mastered the ugly-beautiful style to great effect. The Hanging takes his work to new heights, with certain pages bringing to mind that work of José Muñoz.

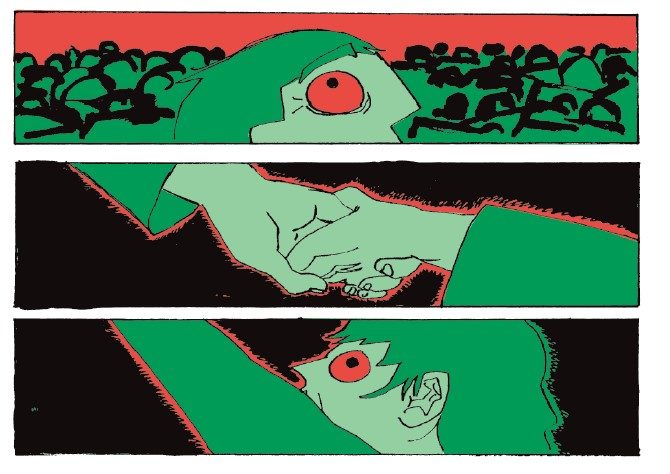

Basing your work on Muñoz, or “copying” Muñoz if we want to be less generous, is also nothing new. Keith Giffen made a career out of it. The power of Muñoz, however, is not in the particular way he draws faces, beaten, plumpy, so expressive they almost become impressionist2, nor in the contours of his figures or even the thickness of the line. No, the power of Muñoz lies elsewhere, beyond the realm of simple description of technique. It is the ability of his art to vibrate through the page with anger (at an unjust world), hate (at those who would perform such injustices), or love (at the few shining things that make life worth living). And on some pages in The Hanging, Losty does just that.

Take a look at this brief panel sequence. On the face of it, it is an extremely simple scene, drawn in the most basic way. The audience in the background of the establishing panel is shown with a lack of detail, just a few lines suggesting a larger presence. The following panels have no background art at all. Everything meaningful is put in the center of each panel, every one of which features just one main object -– half a head looking up, a pair of hands clasping, another face looking up. It is extremely simple and extremely good. Losty draws only what is necessary for the impact of the scenes; he omits everything else, and the results are panels of pure impact that do not seek to distract the reader with unnecessary artistry.3

Not the whole of The Hanging reaches this bar, but, even at his ground level, Losty transcends many artists with decades of experience over him -– and when he reaches his heights, he reaches some heights. Not an artist to look for, but an artist that is already there.

The Hanging’s power is in its emotional validity, not in its world building, not in its critique of power, but in its presentation of that small family unit, the way we gasp how each of these people feel about the other immediately, from glances and body language, to the way they react to everything around them, the story shows them operating within a world that is already doomed but not loosing their humanity. I’m not quite sure what to think of the book as a whole. When I first finished it I felt as if it was too short, as if it was rushing for a conclusion and losing sight of its ambition. After a while, I thought that maybe it’s a bit too long, losing some of its emotional impact as the (rather obvious) plot drags to its inevitable conclusion.

But maybe The Hanging is exactly the right length to be what it is. Which, for all the familiar trappings and obvious influences, is a work all of its own: a shout of pain and rage rising from the bellow into a siren that’s out to deafen the whole world. This is less of a story worried that a mob would drop on its head, this is a comic that sets out to be the bomb.

- “The Party seeks power entirely for its own sake. We are not interested in the good of others; we are interested solely in power, pure power.” – George Orwell. ↩︎

- Though the short boxing scene in The Hanging is probably the closest Losty arrives at aping the master – that broken face and split lips look like they could come from one of the character gallery at the back of Joe’s Bar. ↩︎

- I believe it was Geof Darrow who, when describing the contrast between him and someone like Alex Toth, claimed that he needs to use 10,000 lines because he isn’t capable of expressing things in one. Toth’s simplicity, of course, is very much unlike that of Munoz – stressing out clarity of storytelling over emotional directness. Toth was better storyteller and a lesser artist than Muñoz; showing simplicity is a tool like any other, not a direct path to artistic greatness.

↩︎

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply