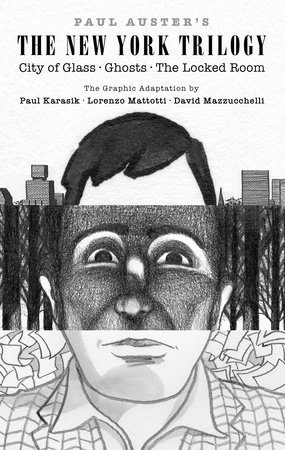

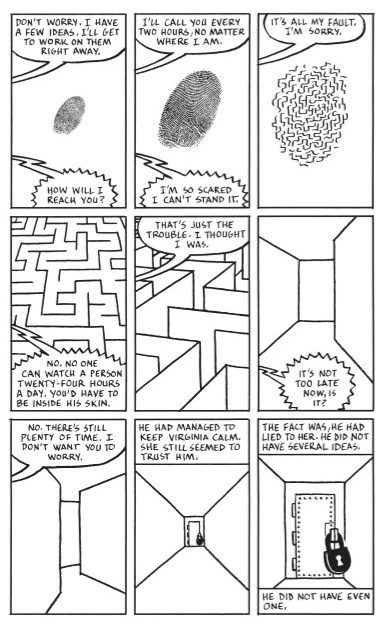

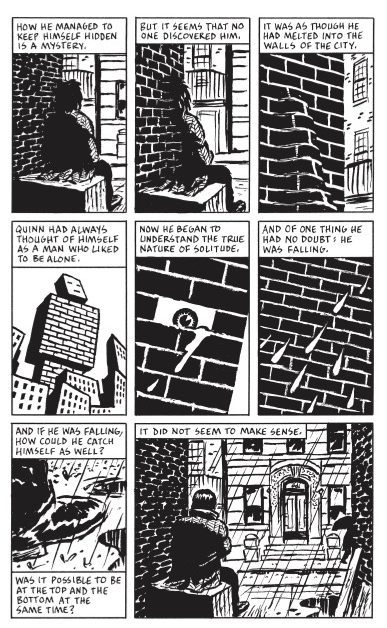

This summer, I had the pleasure of reading Paul Karasik’s graphic adaptation of Paul Auster’s The New York Trilogy after being sent an ARC from Pantheon. Karasik’s use of white space and panels reminded me of poetry, and his sequential art invited me into Auster’s classic detective story by following a principle rule we often parable in the world of Creative Writing: show, don’t tell. The combination of prose and sequential art added to the suspense and heightened the impact of Auster’s words. I was blown away by each book and found myself tabbing page after page to study the pure mastery of the form. So I found myself lucky when I got the opportunity to speak to Paul, while he was in Saratoga Springs on a residency, about his experiences adapting Auster’s work, the coincidences that led to it, and his career as a cartoonist.

Two-time Eisner Award-winning cartoonist and educator, Paul Karasik, began his career as the Associate Editor of Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly’s RAW magazine. He has subsequently worked on scholarly books about comics (“How To Read Nancy” with Mark Newgarden), co-written an award-winning comics memoir (“The Ride Together: A Memoir of Autism in the Family” with Judy Karasik), and edited comics collections (“The Complete Fletcher Hanks”). Many of his former students have become notable cartoonists. Paul’s work has appeared in The Washington Post, The Nation, The Boston Globe, and The New Yorker.

Lara Boyle: How is adapting a prose novel different from an original graphic novel and what is the process like for that?

Paul Karasik: Well, the only other longform piece that I did was a memoir with my sister called The Ride Together and it’s a memoir of autism in the family; it’s about our relationship growing up with our older brother who had autism and the challenge there, the numerous challenges there, but in that case we had to create a story arc out of our lives. Human life doesn’t necessarily lend itself to a natural, engaging story arc. So, how to take events that actually happened and transform them into something that has some engagement over a couple of hundred pages, that’s the challenge. Whereas with Auster, um, these three novels, the challenge was more like, how do you translate something that already has a story arc, maintain that story arc, and do something new with the material in another medium?

Lara Boyle: I went into this having not read the original, Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy. Were you hoping to reach people who maybe hadn’t read the original by making it a graphic?

Paul Karasik: Sure, I guess so. Yeah, I mean, I think it’s probably most fun for people who have read the original already, and are familiar with it, and maybe they’re fans of Auster or maybe not, and they want to revisit the material in a new way. At the same time, being faithful to the beloved trilogy that they enjoyed years ago, I think that’s the most fun for people I’ve talked to who said, “Wow, it’s so much like the original, it’s so faithful to the original, and yet it feels like a fresh piece of work.”

Lara Boyle: What does your routine look like for creating a book like this? Do you start with the words or the pictures?

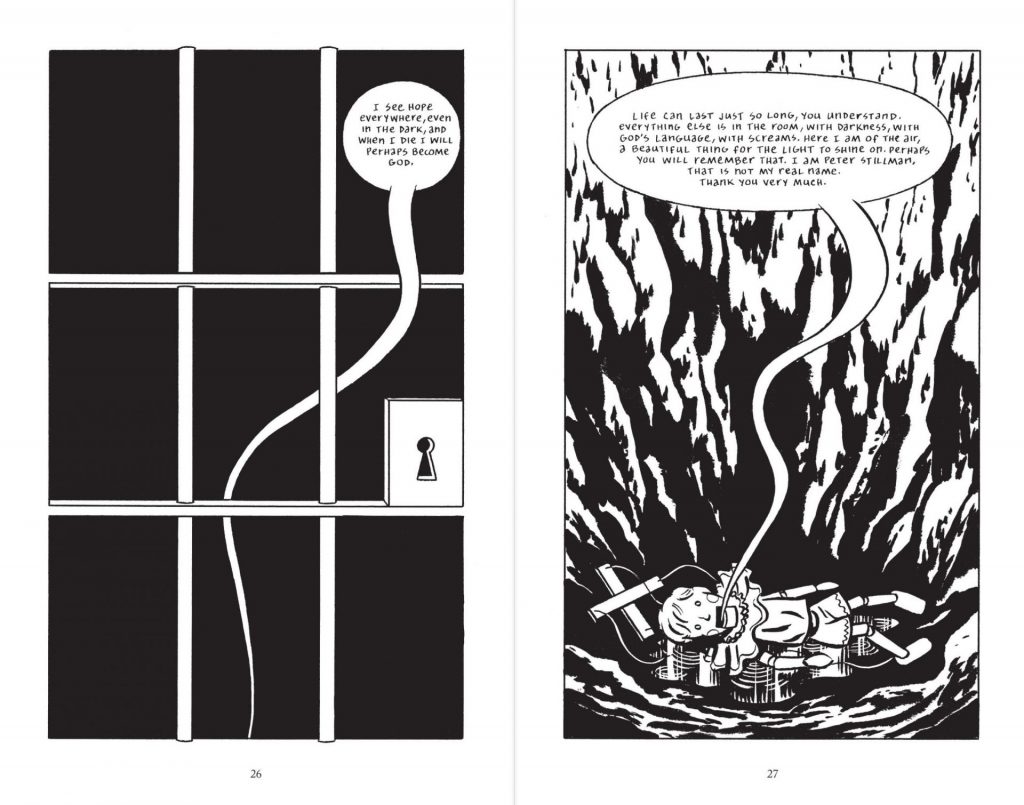

Paul Karasik: Well, of course, since it’s a novel, I start with the words. And so with all three books, I had a copy of it, and then I would mark up the copy and determine what I wanted to show visually, highlight it in one color, and then highlight specific words I wanted to use from Auster’s original text, in another color. And that was sort of the jumping-off point. Auster was very clear from the beginning, and that beginning now was thirty years ago, you know, when we did the original version of City of Glass, myself and David Mazikelli, and Auster said, “This sounds like an interesting idea, go ahead, do whatever you wanna do, but every word in the adaptation has to be a word that I’ve written.” And so, immediately, uh, that restriction actually gave me a tremendous amount of freedom to be able to hunt and peck and choose the words I wanted to use.

Lara Boyle: When did you discover Paul Auster’s work for the first time?

Paul Karasik: Well, the New York Trilogy came out and was done in 1986 or 1987, something like that, and very shortly afterwards, I read the entire book, all three books, and, uh, it’s a kind of bizarrely Austerian story of how it all came to be. Paul Auster’s books are often peppered with coincidences and unexpected circumstance, and, in this case, I’d read the books and I’d made some little sketches in my sketchbook – I always keep a sketchbook nearby, thinking about how City of Glass in particular might make an interesting comic, and I read those books because Paul’s son was a student in one of my classes, I was teaching at a prep school in Brooklyn Heights, and little Auster was in my class. So I thought, if I read the books, when Paul Auster comes in for teacher conferences, and, you know, I can schmooze up to him. But when he came in, we never talked about the books, we just didn’t, because we had a lot to talk about with young Daniel. Then several years went by, and I never thought about it again. I wasn’t serious about it to begin with. But I moved to the country, and the phone rang, also another Auster earmark, and it was Art Spiegelman who was my, really, my mentor and whom I had taken classes with, and subsequently the associate editor of Raw Magazine, which he published with his wife, Francoise Mouly, and Art said, “You know I’m helping an editor here adapt some contemporary noir novels into graphic novels, and we chose a really hard one, I don’t think it’s possible. I think you might want to take a crack at it.” I said, “What is it?” He said City of Glass. My jaw dropped. City of Glass? I’ve already started. So that’s how it all came about.

Lara Boyle: How did Art Spiegelman influence you as a mentor?

Paul Karasik: Oh, well, Art’s impact on my life and work is incalculable. I took some classes at the School of Visual Arts with Art, and I took a class with Harvey Kurtzman, with Will Eisner, but I can remember that first class I took with Art. I went in with some swagger, thinking I knew all about the history of comics and how to think about comics, and I was just kind of taking these classes just for fun because I was a comics geek. I never thought I could be a cartoonist. I didn’t really have a great deal of confidence with my drawing. And that first class was just sensational. You know, a lot of people just know Art Spiegelman as this great cartoonist, he’s also a superb teacher, and I say that with all sincerity. I’m very critical of teachers as I’m very critical of cartoonists. I’m a teacher and my standard for teaching is very high. I know a great teacher when I see one, and his impact began with that first class. Then, shortly thereafter, Art and Francoise asked me to work with them on Raw Magazine, and I learned several different things from that. If nothing else, how hard it is to make comics, how time-consuming it is, and the best comics are made without compromise. You just stick with your guns. You might not hit it the first go around, but if you really work hard and stick to your artistic guns as well as your moral principles, the chances are you’re gonna make something that’s worth printing.

Lara Boyle: Have you ever had a moment making a comic where you doubted the process or what you’re doing?

Paul Karasik: Constantly. Doubt is a part of the process. And when you begin to doubt your work, that’s when you can turn that doubt into curiosity. When you start being curious about what it is that you’re doing, instead of moving rotely through a day’s work and begin to ask questions about what you’re doing and why you’re doing it, chances are you’re opening yourself to reinventing or at least minor edits.

Lara Boyle: Do you remember the moment when you knew you wanted to be a cartoonist or when that became a possibility for you?

Paul Karasik: Not so much the moment, but I can remember the period of time, and it has to do with the creation of City of Glass. Because when I started doing the breakdowns for that book, I had had some work published before The City of Glass, but I had that very strong period I’ve had from time to time, that I just know that I’m on the right track, that all rockets are firing. And that feeling, when I had that feeling with City of Glass, I’d had it a little bit before, but I flew through that, and, perhaps, because it had been stewing in the back burner in my brain for a number of years, the whole thing just came about.

Lara Boyle: When did you get to the Yaddo artist’s retreat?

Paul Karasik: Three weeks ago, so I’m about halfway through.

Lara Boyle: How has that changed your creative output compared to when you’re at home?

Paul Karasik: When I’m home, my work comes not first nor second but third on the list of things I need to do. So when I’m here, all I do is work. And I have to socialize at supper, but I try to get some exercise every day. I’m in the studio by 7:30 or 8 in the morning and there until 10:30 or 11:00, and it’s a wonderful luxury to me. And I know what a privilege it is, and I want to make every second count, so I’m very driven to get a lot of work done, but I’m also having so much fun doing it. It’s not like I’m beating myself up like – oh you’ve gotta work, you’ve gotta work – it comes very naturally to me to take advantage of this time.

On page 351 of The Graphic Adaptation of The New York Trilogy, Paul Auster writes:

“I was a detective, after all, and my job was to hunt for clues. Faced with a million paths of false inquiry, I had to find the one path that would take me where I wanted to go.”

In making The New York Trilogy, it seems that the job of a cartoonist like Paul Karasik is not dissimilar to the job of a detective. In a true Austrian fashion, when the phone rang from Art Spiegelman, Karasik had to answer the call to find the path that would lead him where he wanted to go with the story, and hunt for all the clues in the original prose to solve his own mystery of making the novel new through combining words and pictures. Luckily for us, he succeeded.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply