Kim is undergoing a procedure. It’s a risky one, an experimental one. If it goes well… something happens. But if it doesn’t? Her blood vessels slowly thicken until she dies. This is the opening salvo of Lily and Generoso Fierro’s self-published Vessel, a comic that defies the expectations of linear narrative at every turn.

If anything should be said at the outset of this review, it is that reading Vessel is a lesson in disorientation. There is the beginning of the narrative: the study, the test. That’s reasonably certain. The ending, too, is reasonably certain. But the middle, well, there’s the rub – after Kim counts down from 10 to be put into an induced coma, everything starts to come apart at the seams. Finding a firm handhold from which to launch a review of this book is practically impossible. It seems to twist and turn away from you as a reader, keeping you at arms-length. Perhaps more than anything else, reading Vessel brings you into a sort of psychosomatic experience, wherein you feel a lot of things, but understand close to nothing.

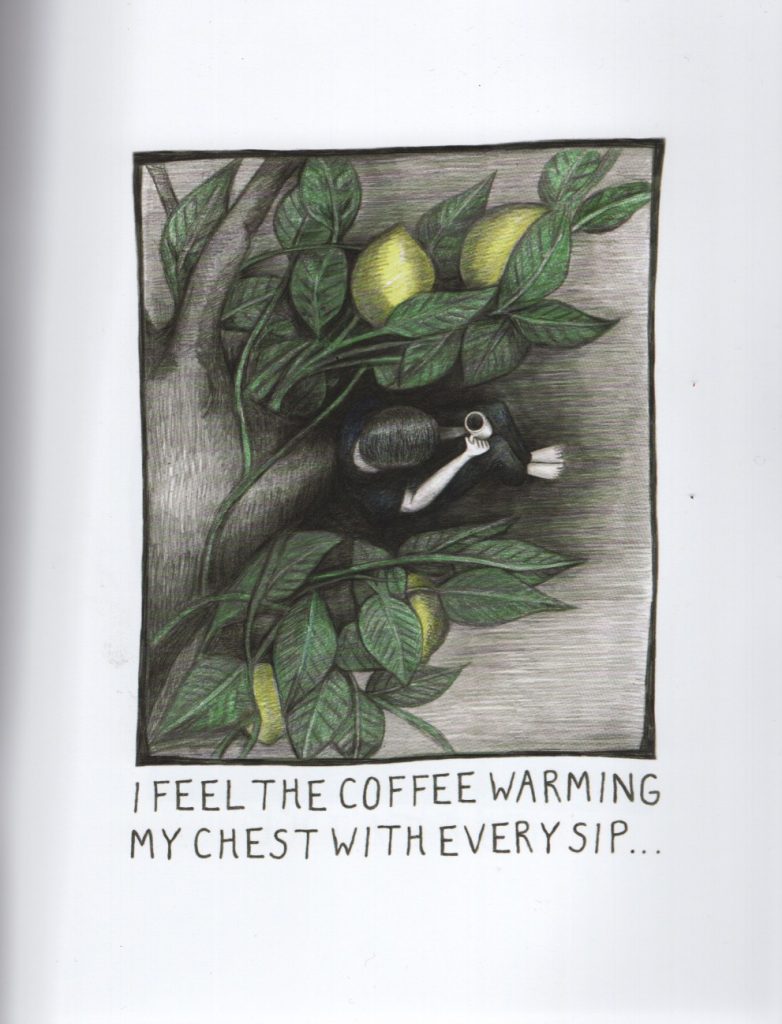

But the Fierros are not keeping everything so close to the chest. Let’s start with the book’s title – like its namesake, Vessel seems less interested in the container and more interested in what’s being contained. You may have a set of coffee mugs, but ultimately they are utilitarian objects, designed to hold that which helps you stay caffeinated. Likewise, your blood vessels are extraordinary in length, size, and functionality, but it’s the blood and lymph that they carry that keep you alive. In both of these examples, it’s what’s inside that counts. In the same way, the characters and scenes of Vessel are the vessels of what is ultimately a sensation or feeling, not a bog-standard version of Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey.

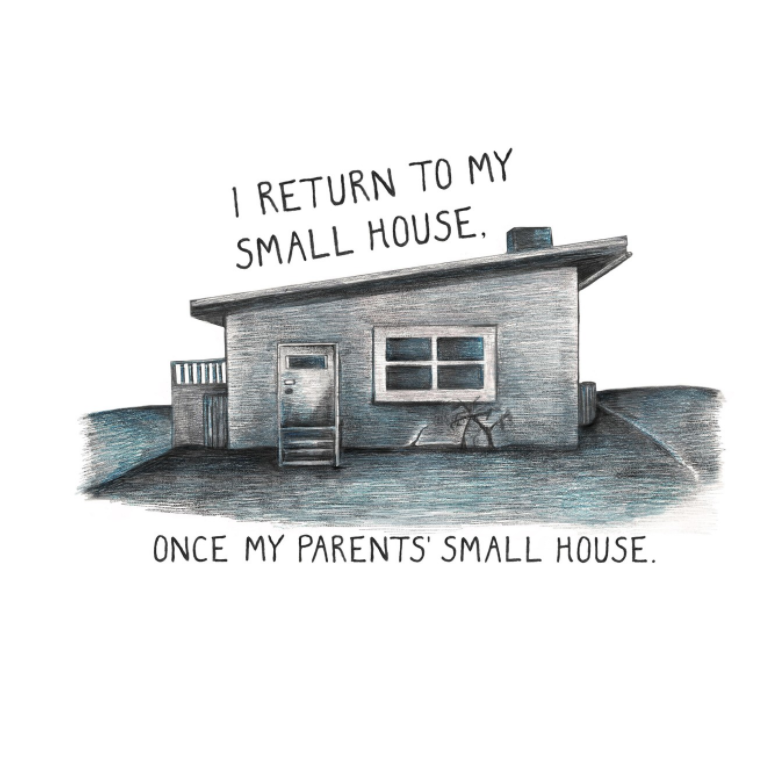

And while the sensation and feeling it evokes are also foggy around the edges, Vessel is open to the reader’s intuition. The heavy use of white space on each page emphasizes a profound emptiness in the world of Vessel that is more easily sensed than seen. Throughout the book, the use of white space along with a thin line and repetitive constrained use of color indicate a muted future, cleaner but devoid of humanity. Kim’s dialogue of exclusion, failure, and death gives us a sense of a world that has given some of its people powerful medical advances while others have been consumed and lost, relegated to fixing massive industrial coffee machines. Kim constantly finds herself stuck in a place where there are no good options. What can be obtained without great risk? Very little. What can be lost? Only the most important things. What has been lost? Almost everything. Set in some distant future, Vessel is both a science-fiction dystopia and a meditation on grief.

Vessel also seems interested in the intersection between powerfulness and inhumanity. Kim sees and hears a mass of hairless white men who complain about their doctors and the 6th generation grandchildren, all the while she is dying a slow and painful death. Given the power to live extraordinarily long lives, these men are more interested (from their complaints) in exclusion than acceptance. Their anger is easily stirred, their faces brutal and unforgiving. Even Dr. Miller, the man behind the procedure that Kim endures, is an emotionless void, delivering bad news without so much as a downward glance.

Despite its somber mood and its synesthesia of sadness, Vessel also finds places of quiet reflection and beauty. A cup of coffee under the lemon tree, a chow chow, pomegranates – all add a splash of color and symbolism that emphasizes life, renewal, hope, blood, and death. While the strain on humanity in the Fierros’ imagined future is great, it is not complete. Despite the unsettling medical procedures, Kim’s sense of isolation, and her impending death, these small visual cues are a vessel, if you will, that contains the remnants of a shared and common humanity.

My ultimate reading of Vessel, if you can even call it that, is one of a sensation of grief, both for the things that we have lost, and the things we will soon lose. During the pandemic, there’s been a lot of things lost – families, communities, rituals, relationships, to name a few. How can you contain that grief? You can’t. You either let it out or let it destroy you. Lily Thu Fierro and Generoso Fierro are using Vessel as a conduit for that grief, and, in its ephemerality and its fogginess, Vessel acts as both a cycle and an ending, one that exists less in the mind and more in the heart.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply