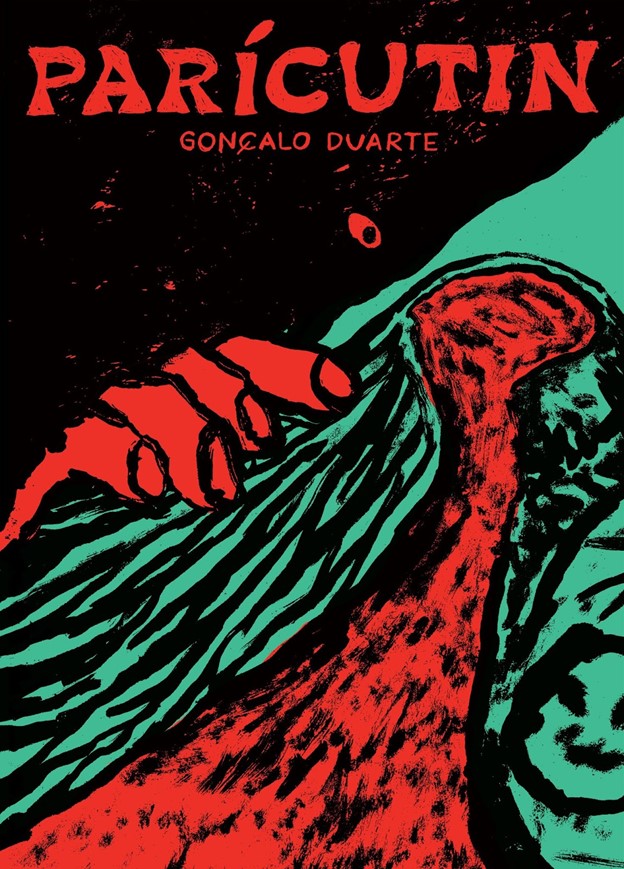

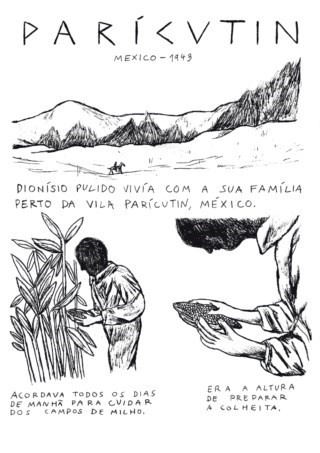

It’s not every day that one comes across a work that is both incredibly straightforward and staggeringly interpretive at the same time, but such is the case with the full-length debut graphic novel from Portuguese cartoonist Goncalo Duarte, Paricutin (Chili Com Carne, 2020). Narratively elliptical, yet — refreshingly enough — in no way particularly confusing, Duarte begins his tale with a Mexican corn farmer named Dionisio Pulido discovering murmurs of volcanic activity in his field in 1943, and from there things really do get well and truly explosive — but not in the traditional manner.

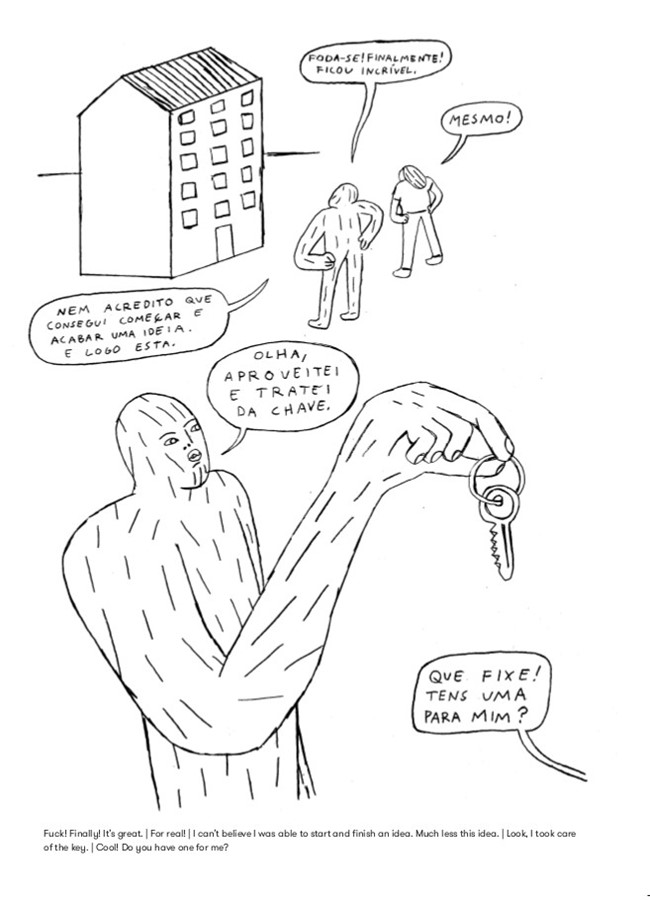

Still, points for historical accuracy: five minutes on Google revealed to this author that Duarte has the particulars of the Paricutin volcano eruption down pat, but Pulido’s story is not the only one the cartoonist concerns himself with — nor, in fact, is it the main one. Rather, the bulk of this text centers around an unnamed protagonist, who would appear to bear certain hallmarks of being an authorial doppelganger, constructing a home with his own hands and setting into motion a chain of events that are, more than anything, a convenient excuse for a wide-ranging polemical dissertation on subjects ranging from displacement to the ethics of land use to the precarious nature of the so-called “gig economy” to intentionally-shared living spaces. To call it generationally specific would be to sell it all a bit short, but the issues addressed are, generally speaking, of extra import to the millennial and post-millennial set.

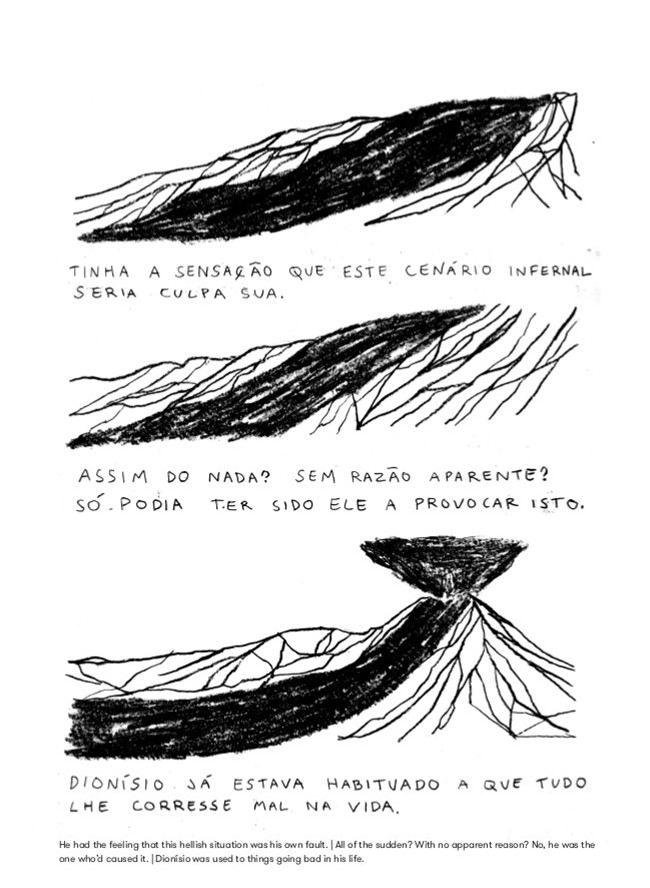

Don’t take that to mean that we completely abandon 1943 Mexico, however. Duarte dives in and out of Pulido’s life, and briefly visits the lives of others as well, in fairly obvious attempts to draw parallels between various “then”s and the here and now, but thankfully those parallels are more subtle — even oblique — than his method of conveying them would lead one to expect. Indeed, there are times when the transitions seem to arrive out of nowhere and occur for almost no reason, but by the time we shift gears again, the previous jump has done the work necessary to at least make intuitive sense. Perhaps Duarte’s real gift, then, lies in his ability to wrap velvet around the head of a sledgehammer and/or to find the tease out the subtleties in visual storytelling techniques that should probably, by all rights, come off as being heavy-handed in the extreme.

There is, then, a delicacy to the proceedings here that’s absolutely noteworthy, and Duarte’s rich and textured illustration plays a large role in conveying that overall tone and mood. Elegant in its simplicity yet never anything less than absolutely accomplished, he has an eye for peeling away extraneous detail and drawing a reader’s attention to precisely what he wants them to see that’s pretty remarkable for a cartoonist with a comparatively thin CV. English-speaking readers such as myself may be taken aback, at least at first, by the need to train our eyes to the bottom of this book’s pages for panel-by-panel translations, but, in the end, it’s to our benefit as it affords us the opportunity to take in the rich — dare I say harmonic — intricacies of each image purely visually first before reading about what we’re seeing, rather than doing both concurrently. And while purists may argue that this alters the artist’s intention, or makes for a fundamentally different aesthetic experience depending upon one’s native language, I say why look a gift horse in the mouth? Serendipity is a rough thing to come by — enjoy it when it presents itself.

Of course, there is a trade-off here in that Portuguese-speaking readers will experience this work in a more fluid fashion, and Duarte’s borderless panels automatically lend themselves to being absorbed fluidly, but this is not, strictly speaking, purely a work of visual poetry — even if it does have a poetic quality to it on the whole. Rather, this is a political work with a definite agenda at its core and a kind of “relaxed urgency” that underlies it. Duarte never breaks his tonal stride, but he doesn’t press it, either, apparently having confidence enough in both his abilities and the intelligence of his readership to, as the cliche goes, let the work speak for itself — which it does loud and clear, provided you’re willing to listen intently as opposed to casually.

Still, at the end of the day, there are a number of decisions that you’ll have no choice but to make for yourself: are we looking at the same place at different stages of its history, or a variety of places? Is the volcano, while historically real, also an allegorical stand-in for exploitative capitalist economics? Could the builder with no name actually be none other than Dionisio Pulido? Does answering these questions differently in any way alter one’s understanding of the book or its central messages? For a comic with a very definite agenda, it must be said that Paricutin is admirably restrained and almost ingeniously subtle. It subverts and confounds expectations in the service of a message that is never anything less than absolutely upfront and direct in its earnestness. Part poem, part polemic, and part puzzle, it is something entirely new and perhaps even unique unto itself — and announces the arrival of a major new cartooning talent who will hopefully be creating exciting, innovative, and thought-provoking content for years to come.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply