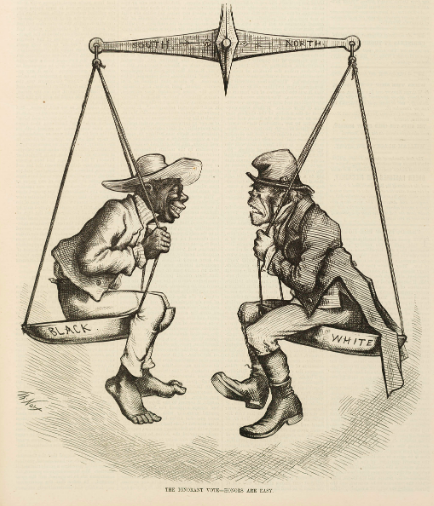

Content warning: this piece contains an image of one of Thomas Nast’s cartoons entitled The Ignorant Vote, which features a racist caricature of a Black man; this image is used contextually to discuss the flaws of Nast’s work. Your discretion is advised.

Thomas Nast hated my ancestors. That much is clear from the famed political cartoonist’s consistent depiction of the Irish as knuckle-dragging ogres. Nast drew demeaning pictures of Black people and Chinese immigrants, too. But he seemed to reserve a special hatred for Hibernians. Either way, I long held an impression that Nast was a racist, nativist Know-Nothing.

But nothing is that simple. While reading Thomas Nast: A Life in Cartoons, a short online graphic biography assembled by members of the Boston Comics Roundtable (BCR), I learned that the man with the poison pen was an immigrant himself, that he was a fierce foe of slavery and the Confederacy, and that he stood squarely behind voting rights for Black Americans.

These revelations were still fresh in my mind on January 6, when thugs waving Confederate flags breached our nation’s Capitol. Never did I expect to see that, nor to then hear myself blurt out, “Thomas Nast must be rolling over in his grave.”

The Thomas Nast biography created by the Boston Comics Roundtable was commissioned by the Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS) last fall as part of a unique, multifaceted virtual exhibit entitled: Who Counts? A Look at Voter Rights through Political Cartoons.

In an exhibit dominated by the Civil War and Reconstruction eras, the prolific and influential Nast casts a long shadow. “Probably the most important cartoonist of the late 19th century,” MHS librarian Peter Drummey called him in his virtual tour of the exhibit.

Nast created or popularized enduring images, such as the Democratic donkey and his own Republican elephant, and our red-suited, white-bearded American version of St. Nicholas, a.k.a. Santa Claus. And Nast proved the power of the pen—and cartooning’s critical place in our free press—when he galvanized public sentiment and helped to take down the corrupt Boss Tweed machine in New York.

The MHS exhibit is packed with iconic examples of Nast’s work such as the above, published in bygone magazines such as Harper’s Weekly and Leslie’s Illustrated News. To boot, the Society presented a webinar on Nast featuring his biographer Fiona Deans Halloran and modern-day editorial cartoonist Pat Bagley.

But the exhibit’s signal original contribution is the bio by the Boston Comics Roundtable. The BCR is a collective of comics creators that meets weekly (currently virtually) and publishes anthologies of stories across various genres, from horror and superhero to history and LGBT issues.

I have to admit that I was charmed right off the bat by Catalina Ruffin’s depiction of young “Tommy,” sketchbook in hand, emigrating from Germany to France to America. It reminded me of a recent children’s book, Just Like Rube Goldberg: The Incredible True Story of the Man Behind the Machines, by Sarah Aronson.

I also appreciated my former teacher Jerel Dye’s take on Nast as a scrappy teenager, earning his first pay as a traveling artist for Leslie’s Illustrated, creating an illustration that would then be transferred to a woodblock engraving. Heide Solbrig gives us a snapshot of Nast’s finest hour—the arrest of Tweed overseas—and Dan Mazur shows Nast at the moment of his Santa’s origin, with the red suit an accident of chromolithography.

In fact, the whole series has a bit of a humanizing effect, considering the nature of Nast’s work—fearless at best, bigoted at worst. On the latter, witness his cartoon “The Ignorant Vote,” in which cruel stereotypes of Blacks and Irishmen are shown as imbecilic pawns of the major parties (a separate section of the exhibit, “Deciphering Political Cartoons,” discusses stereotypes and other symbols and shorthand in the work of Nast and his contemporaries).

As I hinted earlier, Nast’s portrayal of my people as subhuman still stings—and that’s coming from someone who fully recognizes that anti-Irish prejudice is ancient history (heck, we now have the nation’s second Irish Catholic president, and nobody’s raised questions about his citizenship or told him to “go back to where he came from”).

So how must Nast’s similarly simian images of Black men strike BIPOC today who still suffer from the effects of systemic racism?

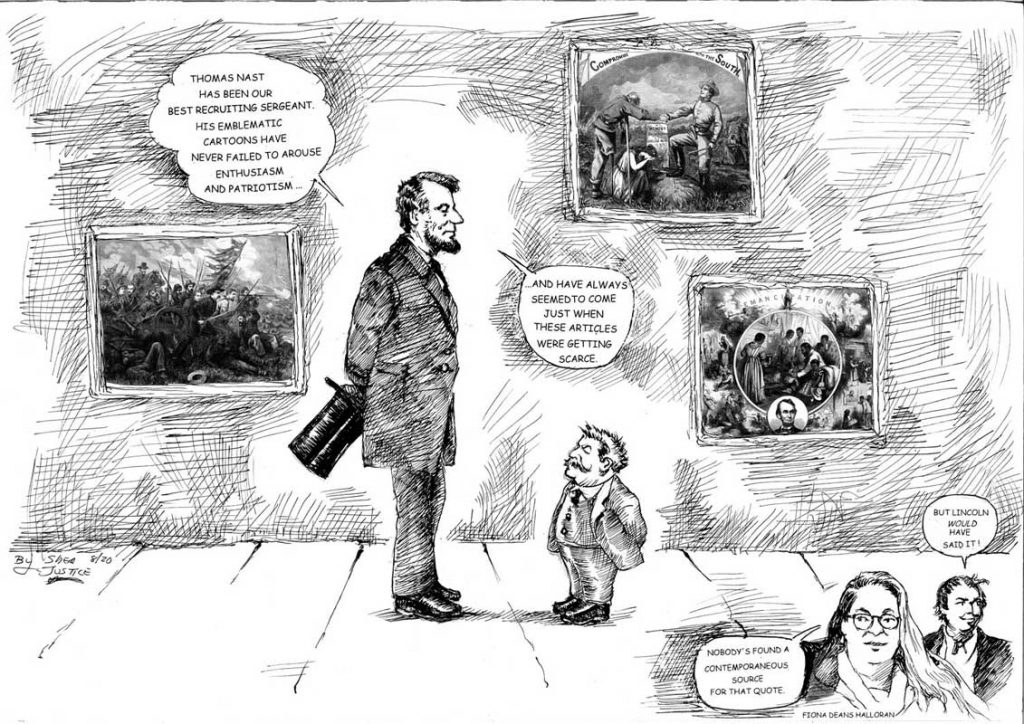

As it happens, the MHS exhibit presents the perspective of one African-American cartoonist, as well as a wider context to Nast’s views. Shea Justice draws the diminutive Nast meeting and literally looking up to his hero Abraham Lincoln. Speech balloons explain that Lincoln either said or would have agreed that Nast effectively served as his “best recruiting sergeant” in the fight to end slavery and preserve the Union.

Behind the pair are some of Nast’s most stirring images in support of emancipation, with Blacks portrayed sympathetically, in decidedly non-caricature fashion. In other cartoons, Nast often belittled Blacks even when he was trying to present them in a positive light, Drummey points out in his tour, but in works such as Emancipation of the Negroes (which Justice reproduces in his cartoon), Nast took the time to show them as nothing but human.

Indeed, one of Nast’s most ambitious cartoons is one in which he was extremely sympathetic to Blacks, conveying his horror at the New Orleans Massacre (which seems a pretty low bar, to simply be opposed to the slaughter of innocent people of any color, but it’s a bar that plenty of people apparently fail to clear today).

The work in question, “Amphitheatrum Johnsonianum,” is substantial enough that the MHS gives it its own, annotated mini-exhibit that is worth exploring. The drawing is massive, complex, every bit as detailed as an oil painting, except done only in black ink. Nast shoehorned telling imagery into every available square inch in a way that recalls later cartoonists at Mad magazine, such as Will Elder and Sergio Aragones. But Nast’s images are caustic, disturbing. He casts Blacks as Christians being mauled in a Roman arena (like many of the cartoons, this one is marked with a sensitive-content advisory). Meanwhile, virtually every “Roman” spectator is an American politician. Not only do their faces need to be identified for the modern reader, but practically their every gesture, costume, and prop carries an additional layer of meaning.

Simply the time it took to draw such a scene lends it solidity and almost demands that the reader engages with the ideas put forth, simply out of respect for the artist’s craft and time. That’s regardless of whether you agree with the artist’s worldview. And in the case of a large-looming, long-careered cartoonist such as Nast, that worldview can often be complicated and contradictory.

The BCR’s E.J. Barnes nails these contradictions when she shows Nast presenting publisher Fletcher Harper with his “Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner,” an optimistic vision of a diverse America. It’s perhaps the one time Nast drew an Irish character who didn’t look like a complete goon. Barnes has Harper hailing Nast’s sentiment: “Every American deserves a seat at our table!”

Barnes’ Nast replies, “Yes sir!” Then he grudgingly adds, “Even the Irish Catholics, I guess…”

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply