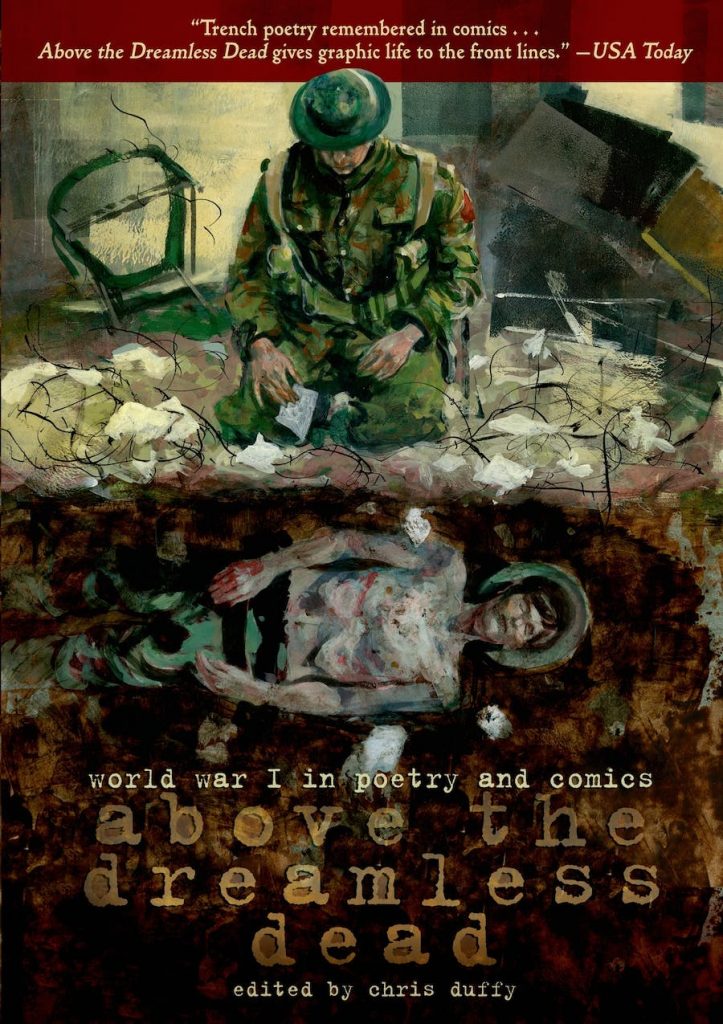

Above the Dreamless Dead: World War I in Poetry and Comics, edited by Chris Duffy, uses artistic adaptations to layer the many contradictions, conceits, and nuanced individual experiences of The Great War. The book is structured in three sections: The Call to War, In the Trenches, and Aftermath.

War is a brutal endeavor. Poetry seems like the antithesis of war, but, like song, it is often the only form that can encompass the depth of feeling and immediacy of the experience. World War I produced several significant English poets. Some were already writing before the war, others were soldiers who found themselves moved beyond prose by the atrocities. Collectively known as The Trench Poets, they have left the world a window into the horrors of trench warfare, the extreme dehumanization of the first predominantly mechanized war, and the reality of what was called “shell shock,” better known today as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

War touches everything. World War I sent a shock wave through the heart of Western culture that still reverberates today. The devastation of land and lives brought people to the emerging profession of psychology. It gave rise to art movements still familiar today, Dadaism and Surrealism in particular. Much of J.R.R. Tolkien’s work is informed by his experiences in the trenches. But The Trench poets were the first to clearly articulate this new view of the world. They were often the first to sound the alarm of gross mismanagement and negligence in the execution of the war.

All of the artwork in the book is black and white and grey. At first, that may seem to be in the reactionary realm of making all things in the past sepia tone, but in truth, color would have made the images lurid and cartoonish. Color would have taken power away from the poets’ words. The book conveys the full depth of expressiveness available in black and white, especially in letting the reader into a world that is steeped in blood and defined by grey areas where absolutes no longer prevail. The variety of artists and styles is remarkable. There is not space here to comment on each poem and the attendant art style that invites the reader more fully into the poem. Much of the painted work is heart-wrenching and dense. There are moments of abstract art that work with subtext and conceptualize emotions in a visual poetry. Cartoony styles, both naïve and underground, provide relief. There are pages that are comfortable reading for people used to standard comic book panels with captions and word balloons, and some that go far beyond those conventions. Each of them does justice to the poem they expand.

The cliff notes version of why WWI began is that Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, presumptive heir to the Austria-Hungarian throne, and his wife Sophia were assassinated in Sarajevo in June of 1914. In response, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Germany went to war with their neighbors. When Germany invaded France by going through neutral Belgium, the UK was required, by treaty, to join the fight on the side of France and Belgium.

Of course, it is more complicated than that. In her 1962 book The Guns of August, Barbara Tuchman tells of the years leading up to the war, the major players, and the events of the first month. That was how long most of the masterminds of the conflict thought it would last. One month. I read her book over twenty-five years ago, and one of the images that has always stuck with me was how, in town after town, the Belgian people came to regard the chorus of men’s voices over the steady beat of marching boots as a kind of terrorism in itself, a precursor to death and disruption. On the other hand, when faced with a future that is unknowable, but where the possibility of imminent and painful death looms large, the urge to sing seems universal. Several of the poems in this book deal with singing.

The first section, The Call to War, ends with All the Hills and Vales Along by Charles Sorely. Kevin Huizenga draws it in a friendly, accessible style. The frames move between the singing, marching men as they traverse the beautiful landscape and the truth that many of those singing will shortly be dead. From a middle verse:

Tramp of feet and lilt of song

Singing all the road along.

All the music of their going,

Ringing, swinging, glad song-throwing

Earth will echo still, when foot

Lies numb and voice mute.

On, marching men, on

To the gates of death with song.

Sadly, this was true of the author, who enlisted in 1914 and died in October 1915 at the Battle of Loos. His poems were published after his death.

Everyone Sang by Siegfried Sassoon, one of the best known of the trench poets, ends the section on the war. It is a single page, with text above two frames filled with singing birds, rising to the sky. Below that, the rest of the words fly with the birds above the land and trees. This poem has been widely viewed to be in celebration of the armistice that ended the war at 11:11 A.M. on November 11, 1918. However, Sassoon maintained that he saw the image of all of the people rising up, like birds freed from cages, as the hope of a socialist revolution, which he maintained was the only sane response to the insanity of the war.

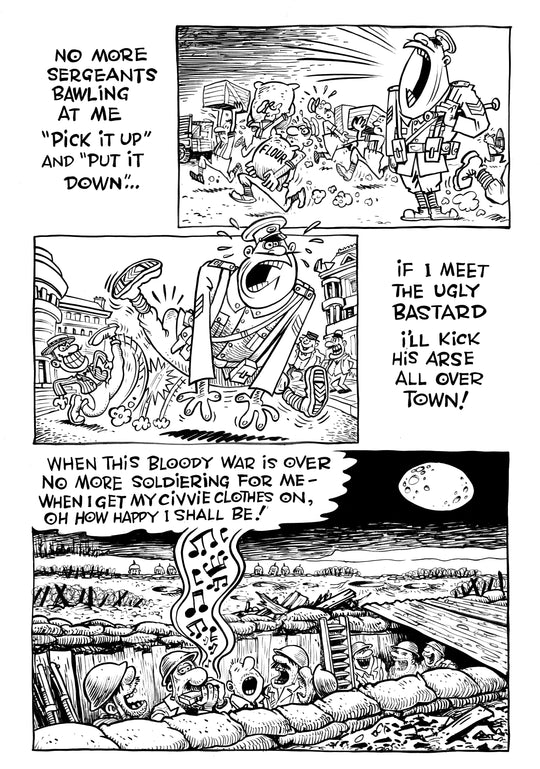

Interspersed in the first two sections of the book is the comic relief of satiric songs that soldiers would sing. I Don’t Want to Be a Soldier, Sing Me to Sleep, and When This Lousy War is Over are adapted by the inimitable Hunt Emerson, who said of his contribution to the book, “Music Hall, the shabby and plucky desperation of working class Britain trying to grasp some semblance of fun and entertainment from the existential horror of their existence. A bit like today, really….” His comment is underscored by the irony that When This Lousy War is Over is sung to the tune of What a Friend We Have in Jesus.

While not about song, The Dancers by Wilfrid Wilson Gibson is exquisitely adapted by Lilli Carre. She depicts a man transported by what he sees. The title of the book comes from the final line. The poem describes the almost hallucinatory beauty of damselflies flitting “Above the Dreamless Dead.” Very apt as the poem gently focuses on the peacock dragonflies that fill the poet’s gaze, while the sky above is filled with screaming black shells. Gibson seems to say that nature will produce life and beauty in spite of the war effort.

Trench life was damp, frozen, or hot depending on the season. It was like endless camping where clever enemies tried new and innovative ways to kill you, while dysentery, vermin, and fear were constant bunkmates. Remarkably, Gibson’s The Dancers is able to see the almost fairytale beauty of glinting wings, nature often inserting herself into the trench in obtrusive and painful ways.

Isaac Rosenberg is responsible for two of the very notable poems highlighting this reality. The Immortals, is cleverly rendered in the slightly blocky, slightly paranoid images by Peter Kuper. Nature’s appearance here is in the form of an insurmountable foe. Kuper’s artwork subjects the poet to blasts of artillery attack from the sky, to machine guns, to bayonets, in a way that casts long shadows of the PTSD to come. But the scourge that ruled the battlefield, on both sides, was the crawling, biting, itch-producing body louse.

Likewise, Rosenberg’s Break of Day in the Trenches is adapted by Sarah Glidden. In an early morning meeting with a rat, the soldier questions how she sees the war:

What do you see in our eyes

At the shrieking iron and flame

Hurled through still heavens?

What quaver, what heart aghast?

Meanwhile, the illustration reminds the reader that the ground is full of nests of rats, without pointing out that they have grown fat on the rations and remains of soldiers from all of the armies in the fray.

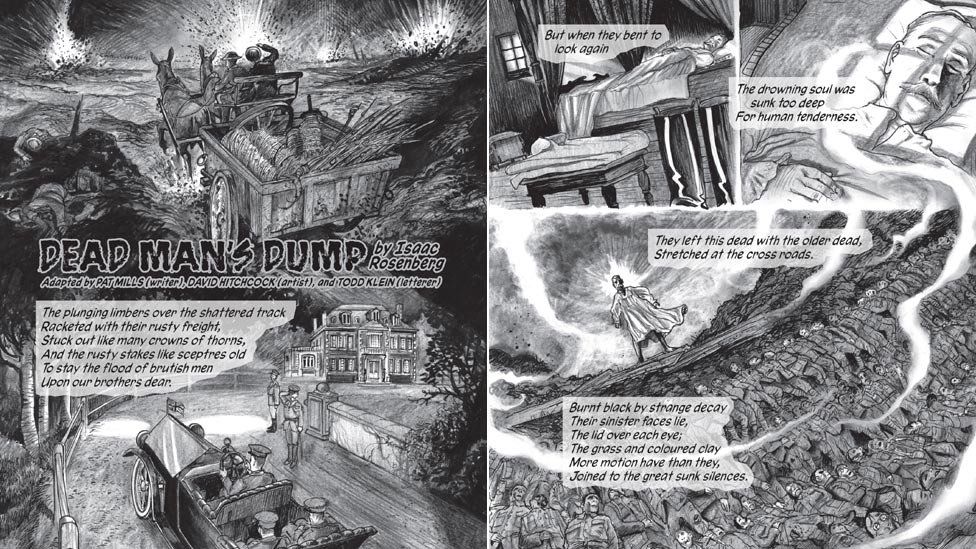

Rosenberg’s work is full of clarity and irony. This collection includes one other of his poems, likely the most well-known of his work, Dead Man’s Dump. It is adapted by Pat Mills (writer) and David Hitchcock (artist) and Todd Klein (letterer). Like something by Poe, it focuses less on the irony and more on the horror, including a pre-death burial in a pile of dead bodies. Yet this work retains a kind of compassion for all of the dead, for all those still living in the nightmare, and for those who seem to be beyond the touch of the war. These different elements are well expressed in Hitchcock’s wonderful artwork, which depicts Rosenberg’s experience on a supply delivery detail bringing barbed wire to the front, as well as the haunted, yet seemingly untouched general with his family and big game trophies. Each has made their way across a roadway filled with the dead, or the nearly dead. A few particularly poignant verses taken from different parts of the poem read:

None saw their spirits’ shadow shake the grass

Or stood aside for the half used life to pass

Out of those doomed nostrils and the doomed mouth,

When the swift iron burning bee

Drained the wild honey of their youth.

A man’s brains splattered on

A stretcher-bearer’s face;

His shook shoulders slipped their load,

But when they bent to look again

The drowning soul was sunk too deep

For human tenderness.

They left his dead with the older dead

Stretched at the crossroads.

Still, not all of the poets in the book are Trench poets. Rudyard Kipling was one of England’s pre-eminent writers by the time of the war. A long-standing champion of the British Empire, Kipling proclaimed the army was far too small for the conflict he saw coming, and he threw himself into the effort of recruiting. Kipling’s only son, seventeen-year-old John, wanted to enlist but was prevented by his very poor eyesight. Kipling was well enough connected to get John a commission in an Irish regiment as a 2nd Lieutenant. Within a month of deployment, John was killed in the Battle of Loos in October of 1915 (it is tempting to think that he met Charles Sorely, though unlikely). The two pages devoted to Kipling’s poem are rendered in Steven R. Bissette’s dappled images so iconic to the Great war; bodies caught on barbed wire, skeletons in the mire of No Man’s Land, and the deep ponds created by endless shelling. This poem is actually a fragment of a much longer poem, Epitaphs of the War 1914-18. Each set of lines is a short chapter which speaks to a different death, some valorous, some tragic, but all caused by the war. Excerpted here is The Coward.

I could not look on Death, which being known,

Men led me to him, blindfold and alone.

Considering the volume of death, an estimated 6,000 soldiers a day, nearly 20 million combined military and civilian deaths, and over 21 million wounded service people, it is hard to imagine anyone actually managing to look away from death. But Kipling belonged to the school of thought that a life given for the Empire was a life well spent. On the battlefield, that sentiment led to over three hundred British soldiers being tried and shot for cowardice when most of them were suffering from debilitating PTSD. This meant that their survivors did not get benefits or recognition for their family’s sacrifice. The final names weren’t cleared until 2006.

Some believe that another of the Epitaphs, Common Form, was intended for Kipling’s own son.

Common Form

If any questions why we died,

Tell them, because our fathers lied.

Thomas Hardy, also a well-established novelist and poet, makes appearances in Above the Dreamless Dead as well. Unlike Kipling, his work tended to be critical of institutions and Empire. His poem, Channel Firing, adapted by Luke Pearson, opens the book. The style is an easy entry, with the evocative images well contained within regularly spaced and sized panels. Written just prior to the war, it imagines the dead awakened by the gunnery practice of the Royal Navy. Fearing it is Judgment Day, they soon learn that it is merely the new normal:

All nations striving strong to make

Red war yet redder. Mad as hatters

They do no more for Christes sake

Than you who are helpless in such matters.

While the poems in the first two sections of the book are devastating in their directness and profound beauty, the poems in the aftermath are even more scathing. The War to End All Wars sadly did little more than set the stage for the Second World War and laid the patterns of increasing mechanization of the process and dehumanization of the soldiers who fight them.

Osbert Sitwell is one of the poets who discovered the call to writing during the war, and Simon Gane adapts his poem The Next War. Gane’s art depicts ten different WWI monuments across France and the UK. In the poem “Those who had turned blood into gold” decide that it is time to create monuments to the dead, the blinded, and the maimed, not only to honor them but also to educate their children. With something between cunning and cynicism, these elders realize that it is time to use those monuments to convince those same children it is time to do as their fathers did and march off to another slaughter.

Robert Graves’s Two Fusiliers was originally published in 1918. But artist Carol Tyler sets the poem in 1963 when an elderly man gets news of the death of one of his fellow soldiers. Tyler is no stranger to war and its lingering effects. Her work has dealt with the scars WWII left on her own father and how that has impacted their family. She sets the stage for the poem, showing the fluidity of memory and how time-healed wounds can be reopened. The poem itself is an ode to friendship that can only be created by the intimacy of overcoming impossible circumstances. Like so much of the art in this book, Tyler’s adaptation adds layers to the poetry without overtaking it or changing the essence of the poem.

Siegfried Sassoon is closely associated with PTSD. Repression of the War Experience is a meditation on how almost anything in daily life could easily mentally transport a person back to the war. Even the things that are supposed to demonstrate an improvement of symptoms, like a steady hand lighting a pipe, come with their own paths back to screaming shells that never go silent. Illustrator James Lloyd weaves the war into the sitting room and garden. Lloyd also adds a wonderful biographical note on Sassoon and tips his hat to all of the soldiers still struggling with PTSD and their efforts to educate the world and advocate for each other.

Sassoon spent several months recovering from both physical and mental wounds at Craiglockheart War Hospital near Edinburgh in 1917. There he wrote Finished with the War: A Soldier’s Declaration. Making him the most outspoken of the Trench poets.

Garth Ennis and Paul Winslade’s adaptation of Sassoon’s The General is done with fine line work, which gives life and vibrancy beyond the specific scope of the poem. The scenes they depict for events alluded to in the poem are potent. A specific battle, Arras 1917, is mentioned in the brief poem. In the following pages, Ennis and Winslade manage to convey the confusion of battle, the hubris of leadership, the abiding love and sacrifice of men (boys really) trying to help each other survive the poorly conceived “plan” that the general has thrust them into. Ennis’s captions manage much poetry of their own. Winslade, and letterer Rob Steen, immerse the reader into the ordeals and emotion.

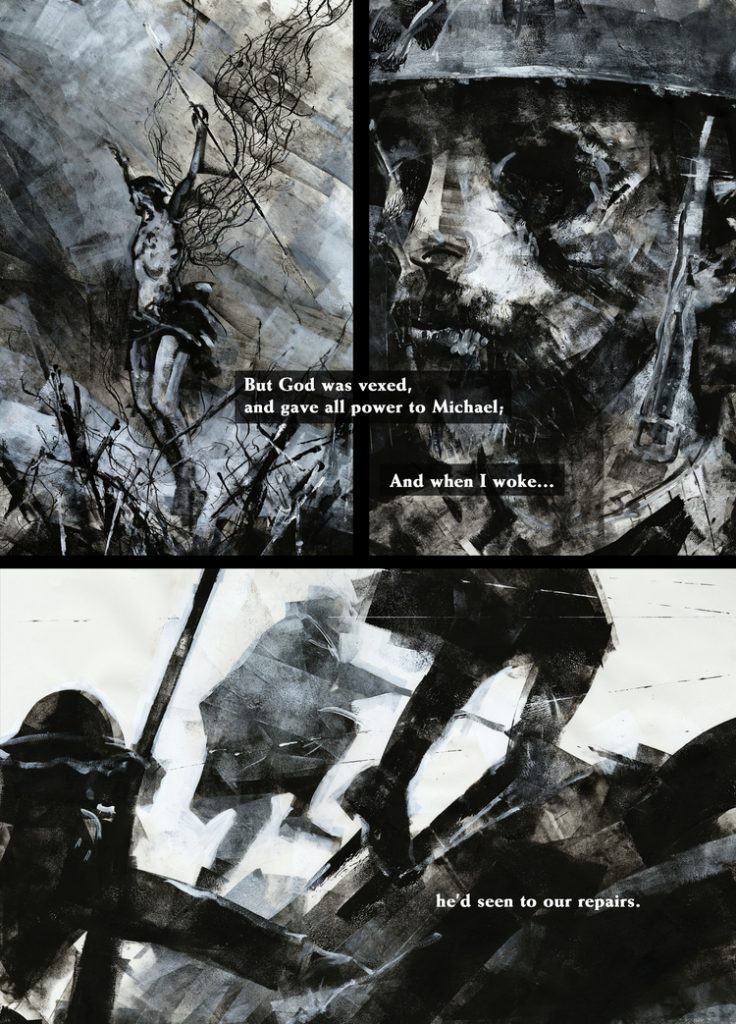

Another war poet, Wilfred Owen met Sassoon at Craiglockheart. Owen was greatly encouraged in his writing by Sassoon. Though Owen died in battle one week before the armistice, he is probably the best known of The Trench Poets, in part due to the efforts of poets and editors Osbert and Edith Sitwell. Four of Owen’s poems are represented here. Artist George Pratt adapts three of them. Pratt’s moody, intense paintings render a perceptive view of the experiences that Owen sought to share with the reader. My favorite of Owen’spoems in this book is Soldier’s Dream:

I dreamed kind Jesus fouled the big-gun gears;

And caused a permanent stoppage in all bolts;

And buckled with a smile Mausers and Colts;

And rusted every bayonet with His tears.

And there were no more bombs, of ours or Theirs,

Not even an old flint-lock, not even a pikel.

But God was vexed, and gave all power to Michael

And when I awoke he’s seen to our repairs.

There are many more poems contained in Above the Dreamless Dead. I could easily go on, but this is a good sampling of what you will find. It is well worth ordering Above the Dreamless Dead from wherever you get books.

In closing, I would like to say that for the people of Ukraine and all the soldiers everywhere, I hope that they will wake from the nightmare of war and that find that the weapons have melted, rusted, jammed, or simply vanished, and that there never needs to be another poem written in “the trenches.”

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply