Easy access to digital platforms and their living archives has resulted in the paradoxical situation whereby culture becomes ever more fleeting and impermanent. One of the best things about book and comic shops is that they are homes to printed work, and that they give this work the ability to sustain over time, to be found and refound, often accidentally and on a whim. It’s not quite a fetishization, though it could be; it’s more an acknowledgment that not all progress is good.

It was in a shop and on paper that I recently came across Marina Groig’s Si me abres la cabeza, sale humo frio, or If you open my head, cold smoke comes out, a 2020 comic published by the Madrid-based Tarde & Triste. Given that the preoccupation with printed matter is partly due to an interest in the fact that it is material, paper seems especially apt for Groig’s work, which is intensely proprioceptive, and preoccupied with the material of people: our bodies, fluids, skin, and bones. The book’s use of glossy paper stock feels like an ironic way to display the tactility of the drawings.

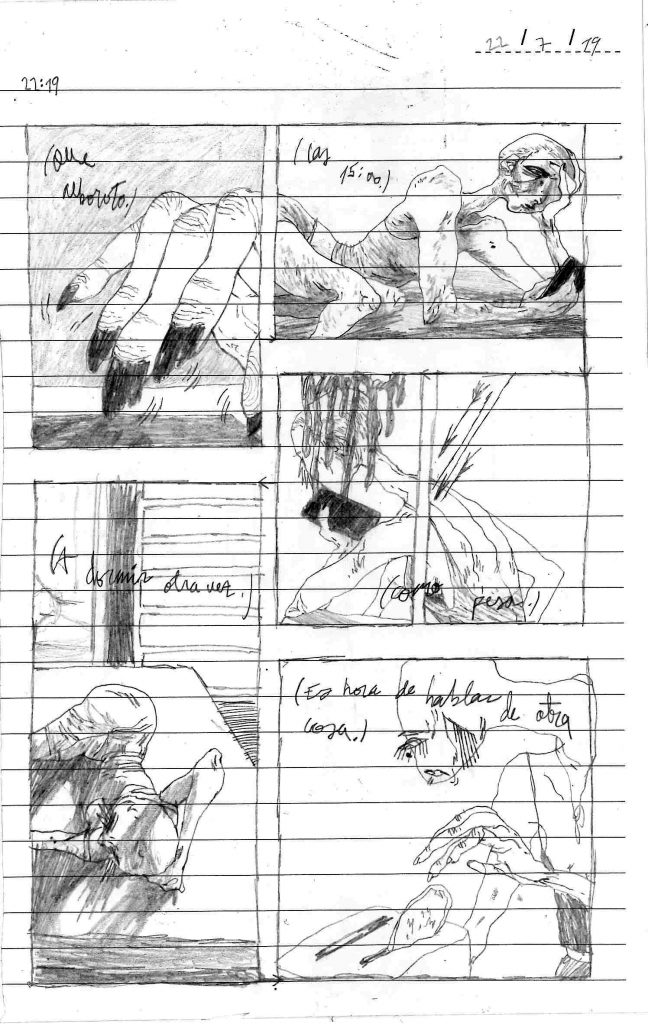

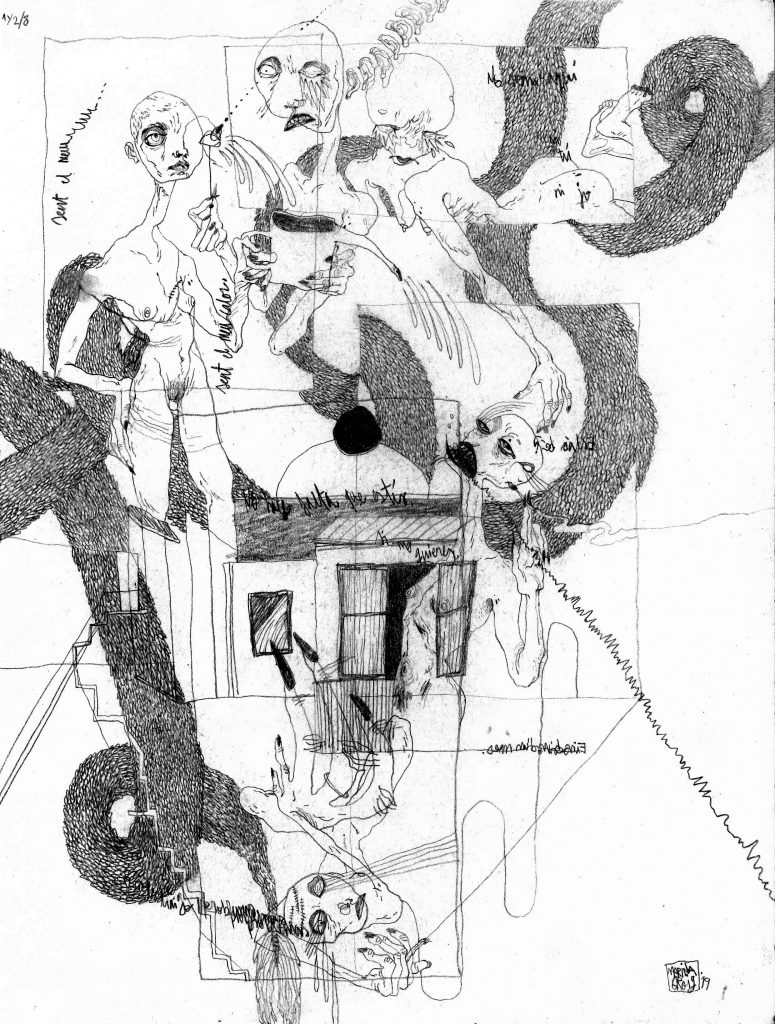

Although mostly a Spanish-language comic, the words in Groig’s images are often difficult to decipher even if you know the language, and the comic reveals itself to be largely nonlinear when you do. In the text, there are elements here of friendship, but also nervousness and anxiety, vengeance and death, eating acid at a family dinner party. At one point the protagonist is having a debate with herself about her desire. Some of the pages are dated, suggesting that these are diary entries, but the information is scattered and splintered. The narrativity of a typical memoir or biography is sidelined – and in any case, I can’t say whether this work is at all (auto)biographical. The typography is scratchy, and at times the words mix in with the drawings. At other times the handwriting is so abstract it becomes more drawing than text.

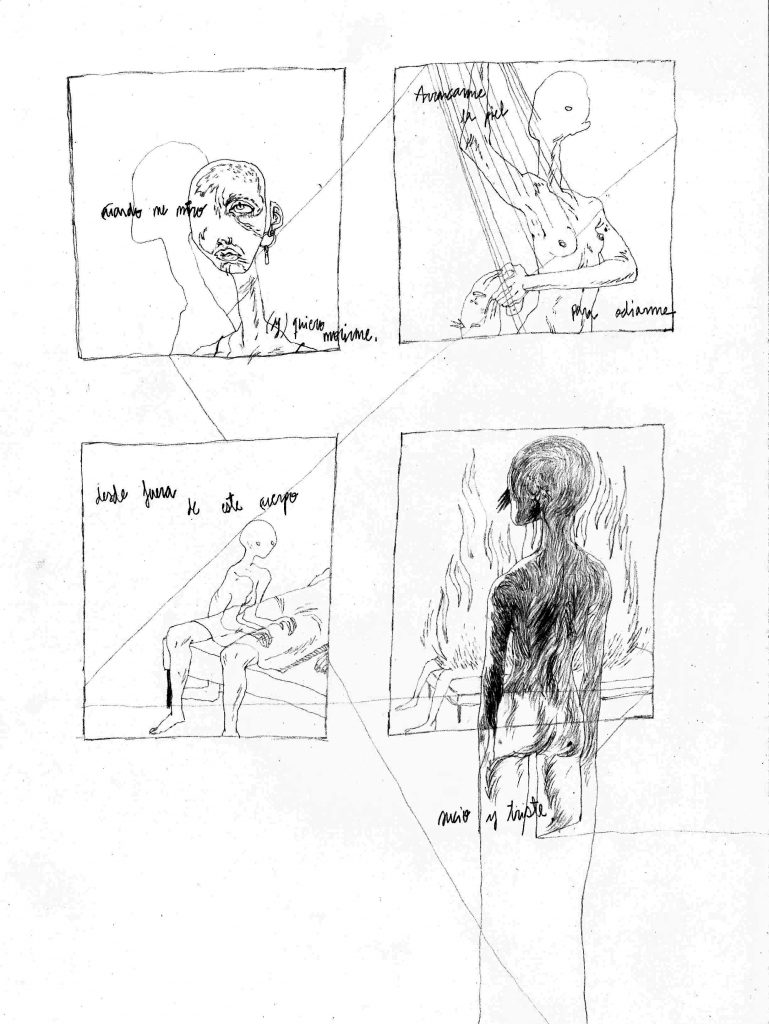

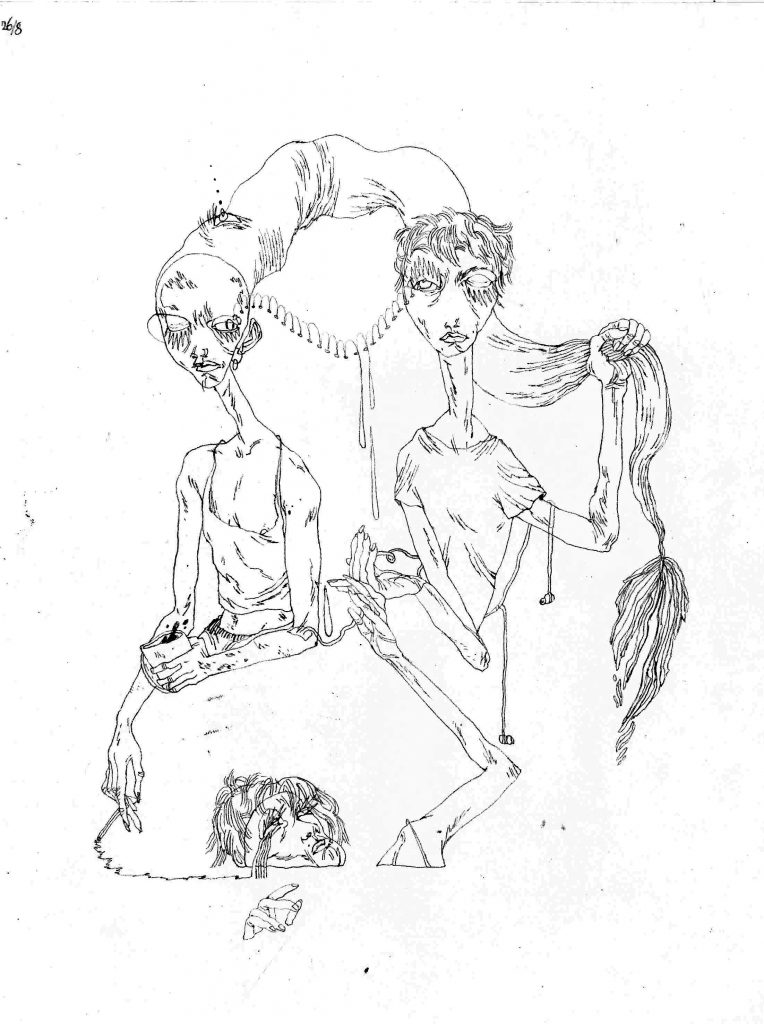

The brief introductory text says that the work is divided into three parts: weight, guilt, and disgust. These aren’t exactly chapter headings, more compass points for the reader to navigate the comic with. Relating these to the panels depicting a figure vomiting, hair being pulled, skin drooping, alongside the intensity of the skinniness of the people, one could come to the conclusion that this is a book dealing with issues related to body dysmorphia. There are plenty of references to food, teeth, and blood, also to pills and medicine, and to family relationships and other types of relationships which seem fractured (could this count as “graphic medicine”? Quite probably). The title points to a lack of self-worth and a sense of emptiness. On one striking splash page, the recurring female character is depicted from a bottom-view perspective. Nude, she tilts her head upwards while a large black mark seeps from a fingernail, partially obscuring what I guess is a blade of some type, while a chorus of “take it off” descends from the sky. There is some unspecified fear and anxiety haunting these pages.

Groig’s art makes this slim book stand out. Her lines are precise but purposefully imperfect. There are a few pages where a standard comics page layout is presented, but in most instances, panels are deconstructed and the pages are composed in a style akin to collage. In one double-page spread, there are panels but the figures burst from them. At times there are drawings on top of unfinished drawings, bare outlines of figures and geometric outlines overlaid with detailed portraits; here the flawed and the unfinished are literal backdrops, possibly a depiction of time overlapping, but maybe also about how people and places can overlap in difficult and straining ways.

The exaggerated features and elongated limbs are reminiscent of Egon Schiele. The focus on the bodily is reminiscent of André Masson’s interest in the same, and there are echoes of his drawings here and Surrealism’s penchant for deconstructing the body and placing the remains in uncanny landscapes. Francis Bacon and Goya are also brought to mind, both being artists who pay tribute to and depict the complications of human beings and their bodies in equal measure.

There’s a gothic, minor key undertone throughout Si me abres la cabeza. Despite not sharing aesthetic resemblances, in its vibe there’s something reminiscent about the more surreal and darker side of medieval and early modern art, the sort that would inspire Hieronymus Bosch – work that at first glance appears to be depicting something otherwordly but in actual fact is interested in the real and fully recognizing it, focusing in on it until it appears alien. Savage Pencil’s punk overtures and Emil Ferris’ faux biography and diarist approach (not to mention her use of the fantastical) are two comics artists whose work has echoes here.

A recurring theme is arrows piercing the protagonist’s body. At one point she is the one holding a bow. An archer in battle with herself, perhaps? Or are these the marks of a martyr like Saint Sebastian? Belomancy is the practice of telling the future through the drawing of arrows from a quiver. Are the arrows here some sort of sign about what’s to come? They are certainly not arrows of movement, rather they appear to pin the protagonist in place. These impressions could only exist as strange, elusive, violent, and enticing images, the type of which If you open my head is composed.

Regardless of these arrows and the other stresses that are applied upon the human here, the body persists and the person is, just in ways that are unexpected and unpredictable, and maybe even undefinable. Much like the paper it’s drawn upon, it may be forgotten by some, but it refuses to disappear. The chapter titles weight, guilt and disgust may point towards the negative, but in recording these sensations and moments, Si me abres la cabeza affirms the strength of persistence and recognition.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply