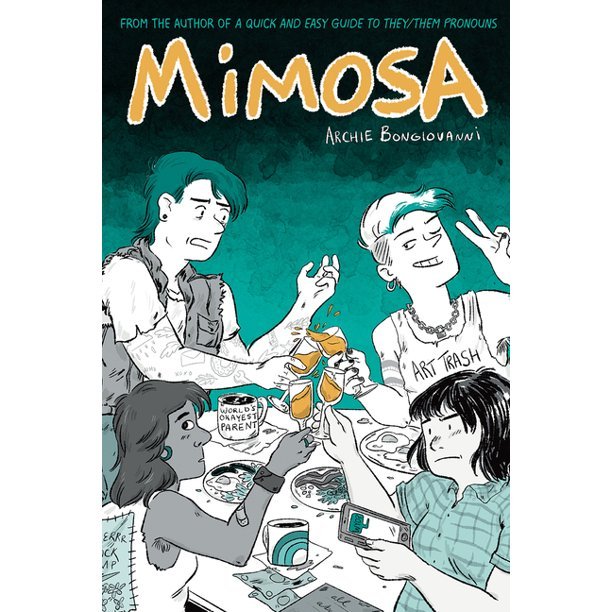

Archie Bongiovanni is an artist whose career arc went in a completely different direction from where they started. In their first major comic, Out Of Hollow Water, it looked as if they were on a path similar to that of Julia Gfrörer: dark, personal, uncompromising, and exploring a lot of trauma. However, their narrative follow-up to that was starting the webseries Grease Bats on the Autostraddle website. It wasn’t just a matter of changing subject matter to funny strips about two queer best friends; even the art felt like a kind of relief. Bongiovanni went from densely-rendered comics to sketchy and, at times, even sloppy drawings that emphasized immediacy above everything else. Bongiovanni carried their new aesthetic into their latest book, Mimosa, published by big house Abrams ComicArts in their queer-themed Surely imprint. The subject matter and the characters in each of these books is so similar that one could see them all hanging out together, but the construction of, and final results for, each book are radically different. Grease Bats looks and feels like a young cartoonist trying to find their footing and needing more structure, while Mimosa sees a more assured Bongiovanni, this time working with what is clearly a firm editorial hand.

It made all the difference.

The essence of Bongiovanni’s work is sloppiness. That’s true of their line and art in general, which frequently feels like it’s in danger of falling apart, but their loose energy is also what makes their comics so compelling. Sloppiness also refers to their highly-flawed characters, who are all messes in their own way. Bongiovanni perfectly captures the messy and neurotic but still fundamentally sympathetic qualities of their characters through their many fuck-ups, arguments, and regrettable choices with regard to drugs and drinking as well as hook-ups. At the same time, Bongiovanni powerfully captures the connection, and acceptance so endemic to queer communities, something that extends to the spaces they hang out in as well as the friendships themselves.

Grease Bats started as a weekly strip on Autostraddle.com. It follows best friends and roommates Scout and Andy, two very messy but lovable queers whose personalities wildly differ. Andy is genderqueer and is all about hooking up, having a good time, and trying not to think about their feelings. Scout is emotionally over-the-top to the point where she’s frequently paralyzed by her feelings. She’s still not over her girlfriend from two years ago. Both love bars and community, and other characters are introduced to round out the cast a bit. Gwen is newly bisexual and outgoing. Taylor is obsessed with academics and just barely beginning to date. Ari is an above-it-all introvert. The additional characters add depth, just as it feels like the strips with Andy and Scout are losing steam.

Starting with “Queeroke,” these strips are as much about the spaces that are crucial to queer life as they are the characters themselves. This story is about Scout and Andy resenting a party bus filled with straight people invading their karaoke night at their favorite queer bar. There are a number of strips about this encroachment as well as the awkwardness of well-meaning “support” from straight families. Mostly, however, the strip is about Bongiovanni exploring different aspects of their own life, as they noted that Scout and Andy are just thinly-veiled versions of their own personality. This plays out in stories like “Feeling the Gender Feels,” which is about Andy dealing with complex feelings about gender despite being genderqueer. An even better one is “Loose Morals,” where Andy plans to sleep with an ex of Scout, who is horrified at the prospect and demands that Andy stop.

All of this plays out in a common description of the strip: an updated version of Alison Bechdel’s long-running Dykes To Watch Out For. Bongiovanni’s art is similarly loose and playful, though they don’t do much to make the strip visually interesting beyond the actual characters themselves. It’s also not nearly as complex, which makes sense, given the shorter span of time, but Bongiovanni seems more interested in exploring archetypes than actual characters (indeed, there’s even a page where they give a shorthand description of each of the main characters with the caption, “Tag Yourself”). The strip does drift from time to time, as Bongiovanni strays from something that resembles actual character interactions and wanders into the characters giving each other lectures, something that Bechdel was also guilty of. The lack of actual, sustained narratives lends itself to this kind of drift, as one gets the sense that the rambling conversations in strips like “Astrology Is Real And Powerful” played themselves out in real life. The collection actually ends with something resulting in a sustained story, when Andy gets a girlfriend and Scout becomes jealous, and then they manage to work it out. When the book focuses on the characters first, rather than something Bongiovanni wants to rant about, it is much more successful.

There were two other major issues with the book: the production values and the editing. The former is threadbare and the latter is non-existent. The two panels stacked on top of three is always a weird choice on the website, and it looks even worse in print. The occasional use of spot color is nice, but the book would have been a lot better if they had spent the time adding color to other strips. There are multiple spelling errors that are uncorrected. It doesn’t do justice to the actual material, and it’s one of the rare times that I preferred simply going back to the webcomics for a better reading experience, and I say this as someone who much prefers reading books over webcomics. Boom! Studios isn’t exactly known for great production values and their Boom! Box imprint is no different.

The good news is that with Mimosa, Bongiovanni was able to work with the Surely team at Abrams, who ensured that they were going to make this comic look good. There’s no question Bongiovanni massively stepped up their game as a writer and artist with this story as well. It still has all of the looseness and tangential storytelling that Bongiovanni excels at, only it’s structured within a fairly tight narrative surrounding four queer friends. Bongiovanni carefully lays out the desires of each character, what’s preventing them from getting what they want, and how they react to this. The intersection of their wants is what creates conflict and sparks a lot of incredible confrontations. It still feels very much like a set of experiences not unfamiliar to Bongiovanni and a lot of messy people who make dumb mistakes, but they’ve done a more thorough job of differentiating each character beyond just a set of archetypes.

Mimosa is set in Bongiovanni’s city of Minneapolis and revolves around four long-time friends who became close working at a restaurant. Chris is a genderqueer single parent, desperately reliant on their friends after a divorce isolates them from their former community. Jo is a trans woman who loves teaching and doing erotic dance, but she’s constantly just barely scraping by financially. Elise is involved in highly fulfilling social justice non-profit work, but she’s tempted by her attraction to her boss. Alex is a trans man and an artist who is always borrowing money from his friends. Their boozy brunches form a rock-solid foundation of love and support and spawn an idea for an over-30 night at a local club, as they bemoan being the oldest queers at the club. That’s the plot hook for this intricate series of social interactions that spark secrets being revealed, relationships irrevocably altered, and an exploration of the ups and downs of chosen family dynamics.

Bongiovanni leans much more heavily on images in Mimosa than Grease Bats, with a lot fewer talking heads scenes, a greater sense of attention paid to backgrounds and establishing scenes, and a more visceral experience for the reader in general. Bongiovanni owes a bit of their character design to another Minnesotan, Charles Schulz. The characters in Mimosa are sort of like if the Peanuts gang grew up and were queer. Elise’s design is a dead ringer for Marcie, and Peppermint Patty growing up and becoming like Chris seems pretty obvious. The result is that the character design is loose and playful but still highly expressive. The green spot color is also used effectively, giving certain scenes a decorative flair and doing more heavy lifting in adding weight and substance to other pages. The whole book seems like it is designed to preserve the spontaneous quality of Bongiovanni’s drawing while giving it more structure, allowing for more sophisticated storytelling overall.

Mimosa opens with Elise recounting wearing out her vibrator watching porn, and that sets the tone for the frequently bawdy, sexy, and frank depictions of sex throughout the book. It was something that was oddly missing from Grease Bats; there was plenty of sex talk, but no actual depictions of sex. Her friends laughing about it over brunch also establishes the easy intimacy they all share, along with slyly setting several plot points into motion. Chris wants to write more on their blog about “parenting beyond the binary” but is distracted by their frustrated libido. Jo talks about how much she loves doing queerrr rock camp but wishes she had one steady job. The slightly frumpy Elise has that steady job but is also sexually frustrated. Alex sets into motion a dance party for “mature queers,” and they dub it “Grind.” Bongiovanni expertly gives the reader a feel for each character’s personality in a way that feels entirely organic, and the hook of focusing on middle-age characters is a nice counterpoint to the frequently youth-oriented narratives surrounding queer culture.

The Grind event is the flashpoint for the friendships fracturing. Simply from a structural standpoint, the way Bongiovanni turns fault lines into conflicts is masterful. The frustrated Chris is abandoned by her wingman (and as it turns out, her housemate) Elise, when Elise decides to make the ill-advised decision to hook up with her boss. When Jo sees some of her teenage students in the crowd, she has to bail on her performance, much to organizer Alex’s chagrin. No one tries to check up on Jo, who is quietly furious. Chris feels betrayed by Elise and vents on how they feel trapped as a single parent. At the same time, the fact they cheated with multiple people on their ex-spouse comes back to bite them on the ass. Alex shows a stunning lack of sensitivity, even as everyone wonders how the perpetually-broke fine artist managed to afford the space. As it turns out, this is all just the opening salvo of conflicts.

Chris chastises Elise for sleeping with her boss, and a furious Elise fires back, saying that while she was taking care of her dying parent in her 20s, everyone else was having fun. Now it was her turn, and she had a right to be messy. She was there for Chris when her world fell apart when their cheating got exposed and was outraged that Chris dared judge her now. No one is there to help Jo process their anger at Alex, and Alex refuses to acknowledge when Jo finally brings it up. Elise moves in with her boss, and things fall apart right before Chris’ 40th birthday. There’s a revelation from Alex that could have been life-changing and helpful for his friends years earlier, and it reveals that their friendship and found family wasn’t quite what it seemed. Or rather, it evolved into something else that he was no longer an authentic member of.

Bongiovanni’s willingness to go all the way with the ramifications of these conflicts, up to and including friendships falling and drifting apart, takes Mimosa in unexpected directions. Rather than contrive a happily-ever-after ending for these friendships, Bongiovanni acknowledges how even the closest of friendships can implode if not continuously nurtured. The conflicts in Mimosa largely stem from the friends making assumptions, taking each other for granted, and keeping potentially damaging secrets. Part of it came from the motivations and desires of each character changing, leading them to grow apart. That was especially true of Alex, who started to care less about the individual feelings of each of his friends and more about the group vibe they had cultivated. Bongiovanni made each character complex and confused about their lives in that moment as well as the future, and they did it in a way that also allowed them to explore a host of queer issues in a more organic way than Grease Bats.

Mimosa feels like the work of a more assured and confident artist than Grease Bats, but that maturity isn’t simply a function of time. Bongiovanni’s development was accelerated through working with a more disciplined editorial structure and a publisher willing to invest in all of the little details that can make the ultimate difference in the success of a book. The fact that the Surely imprint provided all of this without impinging for a moment on the subject matter or all of Bongiovanni’s delightful quirks as a storyteller shows that a good editor isn’t there to impose their will on a book. Instead, a good editor is there to help the artist make the best version of what they are trying to do.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply