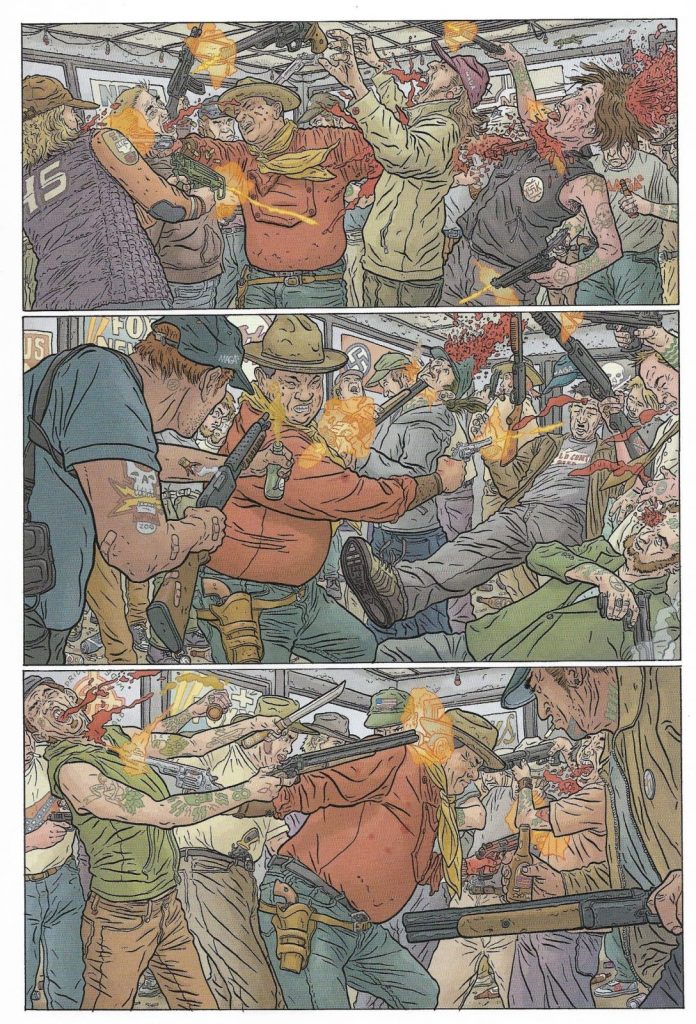

The previous Shaolin Cowboy miniseries, Who’ll Stop the Reign? by Geof Darrow, came out in early 2017. Which is to say – early on in the Trump presidency1. I’m not writing this merely to remind you what was life like in the “before-times,” the fact that Trump was around was a major part of the story. Not so much in the major plot, but in the residual radiation – the story’s depiction of a major American metropolis eaten by hate and racism and violence and consumerism and filth was an obvious, and emotional, reaction by Darrow. In case the least-aware reader possible somehow failed to realize what was going on, the final issue ends with the defeat of the villain, King Crab, that is immediately compared by his conscripted servant to the orange one himself.

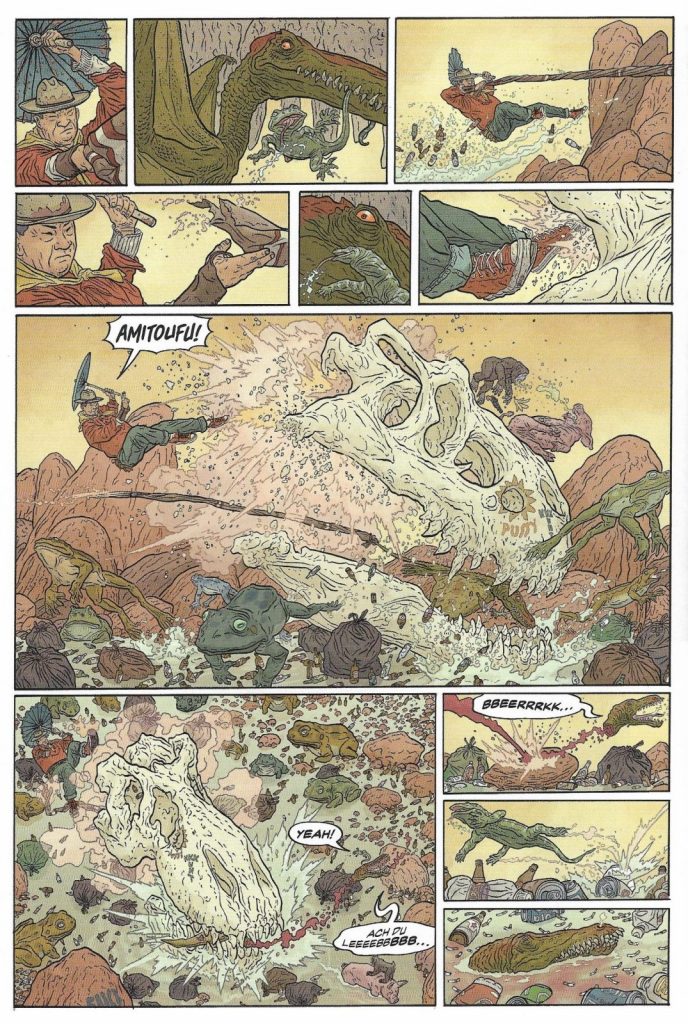

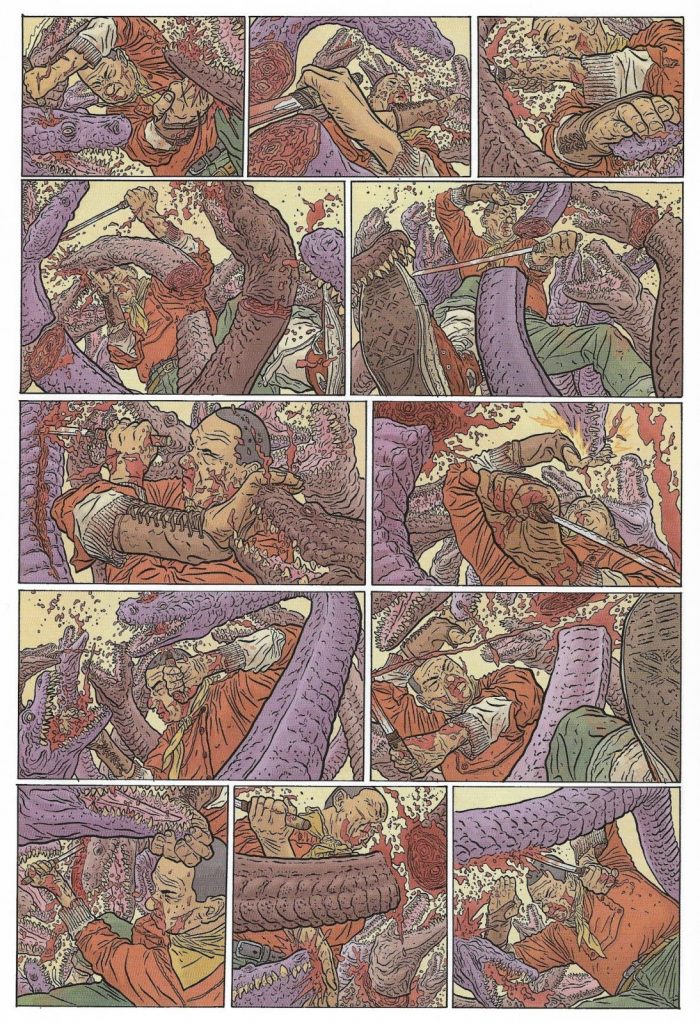

That comic was subtle as two chainsaws attached to the sides of a large stick (a typical occurrence in Shaolin Cowboy). Which is par the course; Darrow is not one for subtlety, neither as a writer nor as artist. His style is dependent upon the all-out assault on the page, filling out every nook and cranny with characters, background, or movement like an evil universe counterpart to Alex “Eliminate the superfluous” Toth. There is no “superfluous” to a Darrow page, from the largest of main characters to the smallest background detail, everything is given the same line weight. Most old masters tend to simplify and become more ‘themselves’ by removing lines2 (like a sculptor working away at a rock, finding the piece hidden inside). Not Darrow, the more time passes, the more Darrow remains similarly indebted to his crazy overwork ethic. After three decades of making comics, he didn’t learn to make more with less, only more with more.

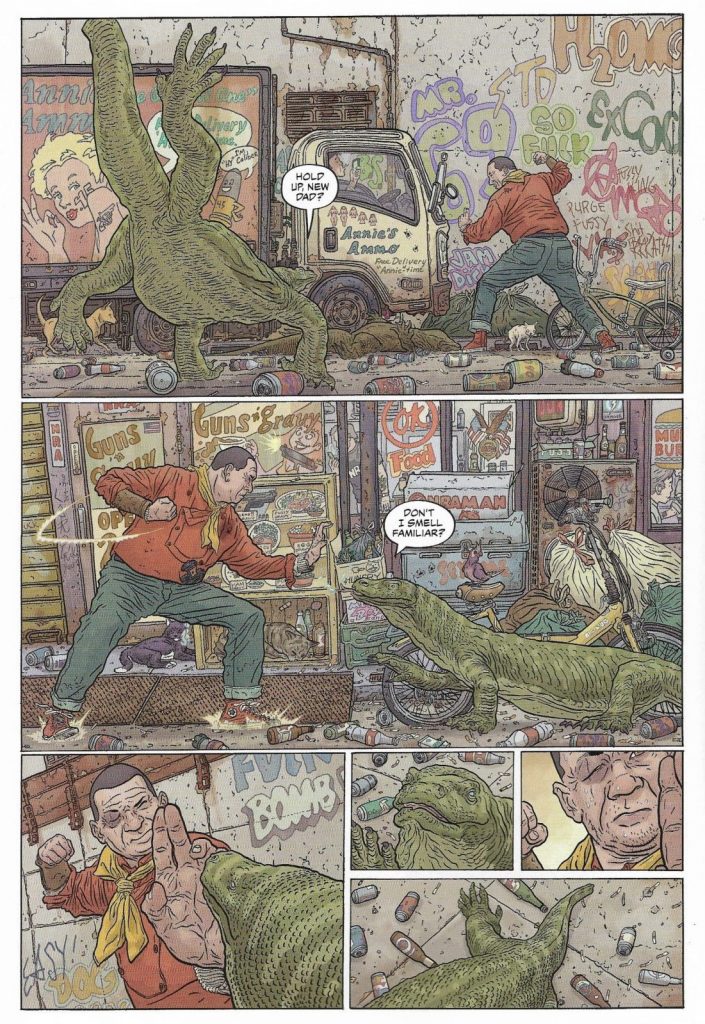

The latest Shaolin Cowboy miniseries3, takes place in the aftermath of Who’ll Stop the Reign?, literally carrying on from the final panel of that story. Meanwhile, in our world, more than five years have passed. This isn’t to say this is some long-forgotten epoch of world history, but it is odd how out-of-synch this series is. It’s both contemporary in its reference and technological presentation, as much as an intentionally idiosyncratic world like that of the Shaolin Cowboy can be “contemporary4,” and already ancient. It appears that the Shaolin Cowboy saga5 is making a long trip from the irreverence of the first series, which was basically a collection of gags and action set-pieces tied with the loosest plot justification possible, to a more politically engaged modern form. I’m not sure this for the best.

Cruel to be Kin’ starts with the Shaolin Cowboy wandering after the long fight before encountering an old acquaintance, for once – not a person trying to kill him. From there on the story is split in half, one is a long flashback to the desert days of the original Shaolin Cowboy series6, and the other is a direct continuation of Who’ll Stop the Reign which even involves a re-match with the aforementioned ninja-pig. This is kinda the worst of both worlds, in terms of how Cruel to be Kin’ is constructed; just like the whole exercise feels several years out of date, so too does the story.

The first half of the series is a return to the days of the original Shaolin Cowboy series, which is magnificent to look at but not so fun to read7. While it’s true that the usual shortness of any Darrow project is borne, first and foremost, out of the sheer difficulty of producing these kinds of pages on any consistent schedule. This shortness definitely helps to focus his energy and kept him from straying too far into the land of “what is even going on here and why should I care about it?8” The first three issues of Cruel to be Kin’ are, like Start Trek, the visual equivalence of these late-era prog-rock albums in which the noodling on the instruments took over any semblance of songwriting. It’s technically amazing, its craft is undeniable. You can’t sit through an entire album in one sitting, though. It’s too much.

These first three issues just keep going and going. Buster Keaton is an obvious inspiration, in terms of the sheer mania of a world-gone-mad meeting an utterly composed individual (no matter what the world throws at the Shaolin Cowboy, he keeps the same stony response); seemingly forgetting there are reasons why the best of Keaton (and others of his era) are in shorts. Darrow never knew when to let a gag go; one of his favorite gags is the fact that the jokes go on for too long, but, even so, there’s a delicate balance of when to cut. The previous two Shaolin Cowboy stories, amongst the best things Darrow ever did, were four issues each. Cruel to be Kin’ is seven issues long, just like Start Trek before its demise, and these extra pages are like an anchor upon the book.

On the other hand, we have the “modern” half of the story. This part involves Shaolin Cowboy befriending a group of talking lizards( just go with it) before being forced, once again, into a cycle of violence. So far the Shaolin Cowboy existed in the same mode as the typical action-adventure story, yet crucially, refused to give the protagonist any positive justification for his violent actions. He’s defending himself from attack, over and over again, but he never fights for something. And as cruel and disgusting as his antagonists tend to be, the narrative does provide many of them at least a thin veneer of justification for hating the Shaolin Cowboy.

This is part of what made the comics work, the manner in which Darrow stripped away any notion of “morally justified” violence – this was violence for violence’s sake, which feels more “honest” than most of these stories that try to find a good reason to make the reader cheer on mass murder. We are people hungry for violence, hopefully only the fictional kind, and Darrow is going to give us what we want until we burst. This is the part in which Darrow’s overworked style becomes the key to the success of these stories: drowning us in page after page of blood and guts that become ever more dissociated than anything resembling reason.

Shaolin Cowboy: Shemp Buffet, one of the single greatest comics of the 21st century, succeeds because it’s almost entirely plotless. There’s a horde of zombies, the Shaolin Cowboy fights them. It’s a literalization of the notion of ‘mindless violence9,’ taken to the nth degree. It’s a gag of the right length that ends on a perfect punchline. I don’t think that some deep satire was something Darrow was aiming for. Darrow appears, to me, closer in spirit to Takashi Miike’s saying: “I don’t have any reasons. I just wanted to do these things.” From that lack of reasoning, from the pure following of artistic instincts, comes the success of so much of Shaolin Cowboy. It’s so stupid it becomes genius. Yes, sometimes Darrow loses himself, not to mention the readers, in his own fancies, but sometimes he finds buried treasures.

The problem with the second half of Cruel to be Kin’ is that suddenly Darrow is insisting upon a reason, a justification, a positive moral cause. The Shaolin Cowboy wages combat after seeing that peaceful family of lizards slaughtered, his enemies are a combination of Fox News parodies and neo-Nazis10. In a scene straight out of John Wick, he takes up a gun he has previously destroyed and straightens it out again. As much as I dislike the intention of the scene, it is beautifully rendered and sets out to mete out justice.

Everything after is exactly what you expect. Darrow is still Daroow, which means even something as plain as a man setting out to kill baddies for some [insert excuse here] promises to be, if nothing else, extremely breathtaking for its sheer skill on display. It’s page after page of action that would probably make other artists’ hands drop from jealousy and/or sympathy pains. And yet, no matter how impressive it is, there’s something lacking here. The purity of Shemp Buffet or Who’ll Stop the Reign? has been replaced by something similar to a dozen other action-adventure comics you pick up from far lesser artists. Not only does the Shaolin cowboy have a good reason to perform violence, but also the story makes it clear to explain that he never actually harmed anyone truly innocent in the previous series, as if trying to clear the name of a fictional character from some imagined slander.

It makes the whole proceeding duller than previous Darrow stories, in a manner that can never be overcome by the wild artwork. Darrow still draws, but it feels almost like someone else, some less led by his id, is writing. Being led by your id has its downsides, see many of the fruits of the Image revolution, but trying to write “proper” can often be far worse.

I realize this whole piece made it sound as if there is nothing nice to say about Cruel to be Kin’, which couldn’t be further from the truth. A lesser Darrow is still Darrow. A Darrow who goes too far is still a Darrow. A Darrow who doesn’t go far enough is still Darrow. There’s more beauty, of the ugly kind, in any random page of Cruel to be Kin’ than in most other comics you pick up this year. This isn’t just a manner of the number of lines Darrow crams into every page, being impressive is not the same as being “good,” but the way he can always arrange them with intent. Every page and panel by Geof Darrow is a statement about the nature of the world, not just a piece of storytelling but a story unto to itself.

Cruel to be Kin’ is a story we’ve seen before, and a story we’ve seen performed better. Not every Orson Welles film can be Citizen Kane or The Trial11. It is no longer 2017. Hopefully, with this project, Darrow had left that year behind and can, like his hero, ride toward the future; and be less like his antagonists – forever anchored by the past.

- I am not writing ‘the first Trump presidency.’ Give the devil an opening and he’ll crawl through it.

↩︎ - Compare early and mid-career Kirby, recognizable stylist but still working in a traditional manner, to the later (and better) Kirby, whose shapes become more blocky and less dependent on ‘correct’ anatomy.

↩︎ - The fourth of its kind. ↩︎

- The series takes place in a ‘present’ ‘America’ with Darrow refusing to commit to any sort of world-building. Dragons and robots and talking ninja-pigs exist within a spitting-distance from rednecks in pick-up trucks quoting twitter memes. Darrow, wisely, doesn’t try to make any sense of it. He draws and writes whatever catches his fancy.

↩︎ - Is there a better word for it?

↩︎ - The one collected by Dark Horse as Shaolin Cowboy: Start Trek

↩︎ - Start Trek became more known for its long-delays than any actual content, which probably only helped it in retrospect: reading one issue per year was like injecting a good-dose of Darrow craziness and sheer artistic wunder. Reading the whole thing at once is like dying of overdose.

↩︎ - A land populated by too many comics creators. ↩︎

- Because zombies got no brains, no personality, no reason

↩︎ - Make whatever redundancy jokes you like. ↩︎

- And since I’ve already mentioned Takashi Miike it’s vital to note there’s a gulf of quality between 13 Assassins to, say, Yakuza Apocalypse. ↩︎

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply