In 1933 my grandparents were all still in their birth countries. On my mother’s side, my grandmother was 11 years old and living in Vienna, and though the interim was not straightforward—a marriage, a pre-Holocaust escape to England, two kids, a divorce—some twenty years would pass before her meeting her second husband, my grandfather, as part of the kibbutz movement in by-then-not-quite-newly-founded Israel; my father’s parents had an earlier start, so in 1933 they were already married, but still in pre-war Warsaw, still unaware that in four years or so they would have no choice to escape with their then-one-year-old daughter to Tel Aviv (then still under British rule) and that in ten years they would have their second child, my father. 89 years hence: if this past stands before me now it is only as a shadow locked behind a towering gate I cannot in any real way open; I know that it is made up of countless wars, countless tumult and shifts, countless loves and deaths, but the second I try to remove this lens of retrospect the totality of its specifics escapes me. This is how the past engages itself: insistent on being accessible only through the mediation of “history” that flattens it into its neat textbook framing.

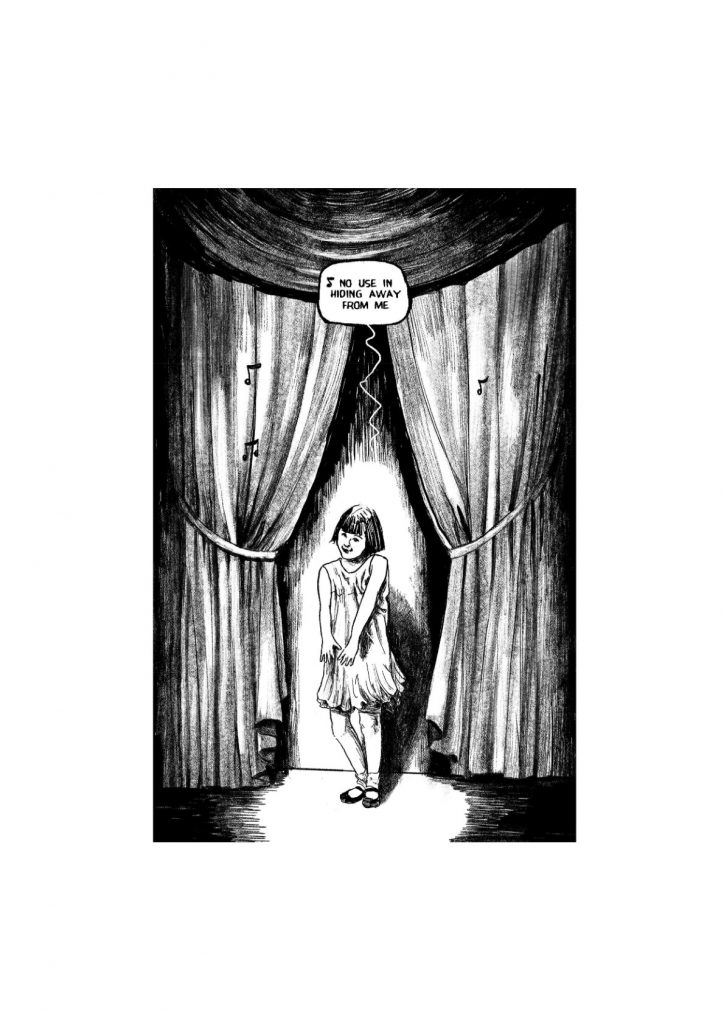

All of this is to say: 1933—the year that ten-year-old Rose Marie stood in front of a microphone and beckoned her listener to “Come Out, Come Out”—was a long time ago. You can hear this gap from the very first seconds of the song itself, as the large, warm jazz-orchestral sound is constrained by the tinny recording equipment, making it sound much smaller than it actually is; the fidelity of Rose Marie’s vocals, too, sounds lacking to any 21st century listener. These technical deficiencies (which, again, only become deficiencies under the scrutiny of 89 years’ hindsight) are complemented by the shifts in musical style: a song like “Come Out, Come Out” sounds crude, unsophisticated in form and lyric, childish in its attempt at whimsy. But, alongside the appearance of crudity, there is also a perplexing, otherworldly impact. The playfulness of the lyrics and implied narrative aspiration is clear, but it feels, simply put, off. The narrator sings to some manner of friend or playdate partner, but the phrases she uses (“I haven’t even met you / except in dreams that are haunting me / still I feel / you are real / I know I’m going to get you / no use in hiding away from me / I’ll find you / I’ll find you”) have not only an obvious menace but plenty of implied questions about the person to whom the song is directed. When presented by the whimsical crooning of a ten-year-old, there is an inherent dissonance—and the path from dissonance to horror is a short one indeed.

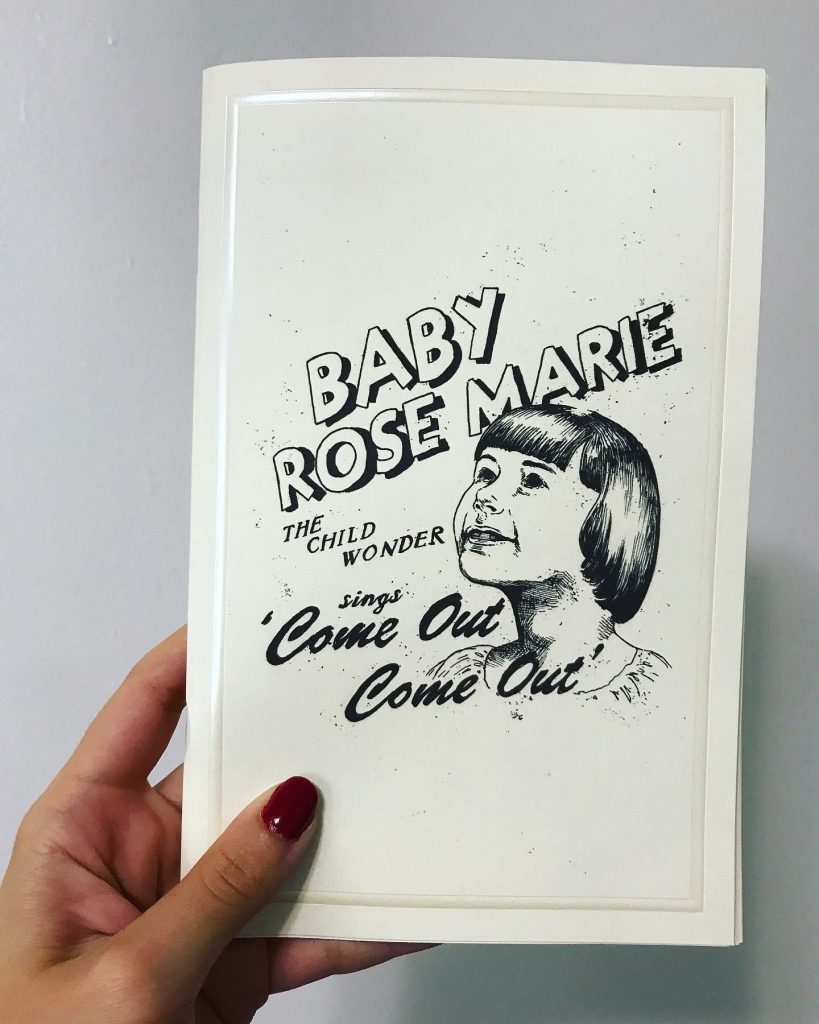

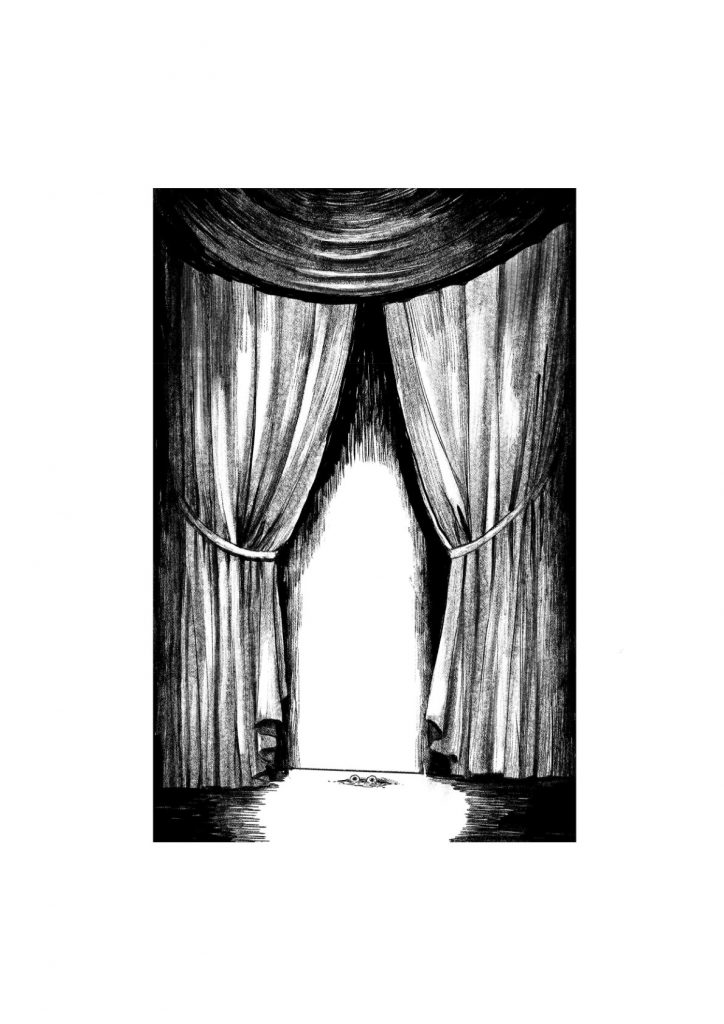

Which brings us, of course, to the comic at hand: for most of the comic, Baby Rose Marie the Child Wonder Sings ‘Come Out, Come Out’ by Jenna Cha does what it says on the tin, presenting a “performance” of the song in question. All of its 48 pages are constructed the exact same way, viewing the star performer and her spot on the stage from the same angle as she materializes, sings (a line or two per page, tops), dances, and then, in her own special way, leaves the stage. What could have been a simple experiment in motion and sensory compensation in comics—adapting a song, which relies entirely on audio and not at all on visuals, into a comic, which relies entirely on visuals and inherently precludes sound—takes on a new and infinitely more gruesome form under Cha’s hand as the cartoonist brings those otherworldly haunting undertones to the surface.

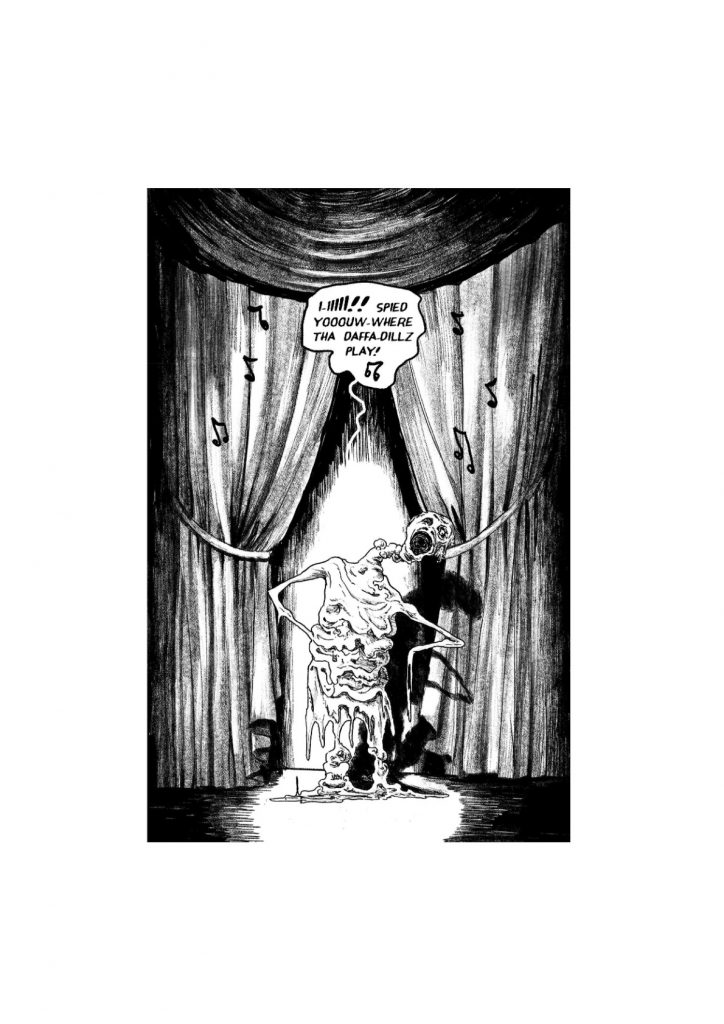

While it could be said to be a “twist,” the wrongness at the heart of the comic is made clear from the very start, as the star of the comic diverges from her real-life counterpart in one very crucial way: she is not, strictly speaking, human. Rose Marie’s materialization on the stage is just that: she appears at first as a pooling viscous mass on the stage, which then grows and reshapes itself into the ten-year-old. She increasingly struggles to maintain that form: as she sings and dances, her face contorts and her legs grow lumpy; as the song progresses toward its inevitable conclusion, Rose Marie gradually loses resemblance to anything that can be labeled human, at first distending and distorting and then, as singing gives way to the orchestral outro, melting and decaying into nothing, leaving only a small viscous puddle with two eyes by the end. Her singing, too, takes a hit—when Rose Marie resumes singing after an instrumental bridge (which Cha depicts as a four-page dance sequence whose childlike charm only lasts for as long as you don’t notice the lumpy masses overtaking the child star’s legs), her “pronunciation” as transcribed in Cha’s lettering starts slipping and losing itself, occasionally rendering “the Milky Way” as “tha Mill-kee Way” and “daffodils” as “daffa-dillz.”

In terms of pure visuals, Cha’s art style can be described as an ersatz-realist line; her textures and rendering are meticulous and considered, the proportions and compositions entirely even-handed and grounded in something adjacent to those of our world. Even in places where the anatomical infrastructure falters, it is hard to determine if it is accidental or completely intentional, so totally cohesive is the work’s atmosphere.

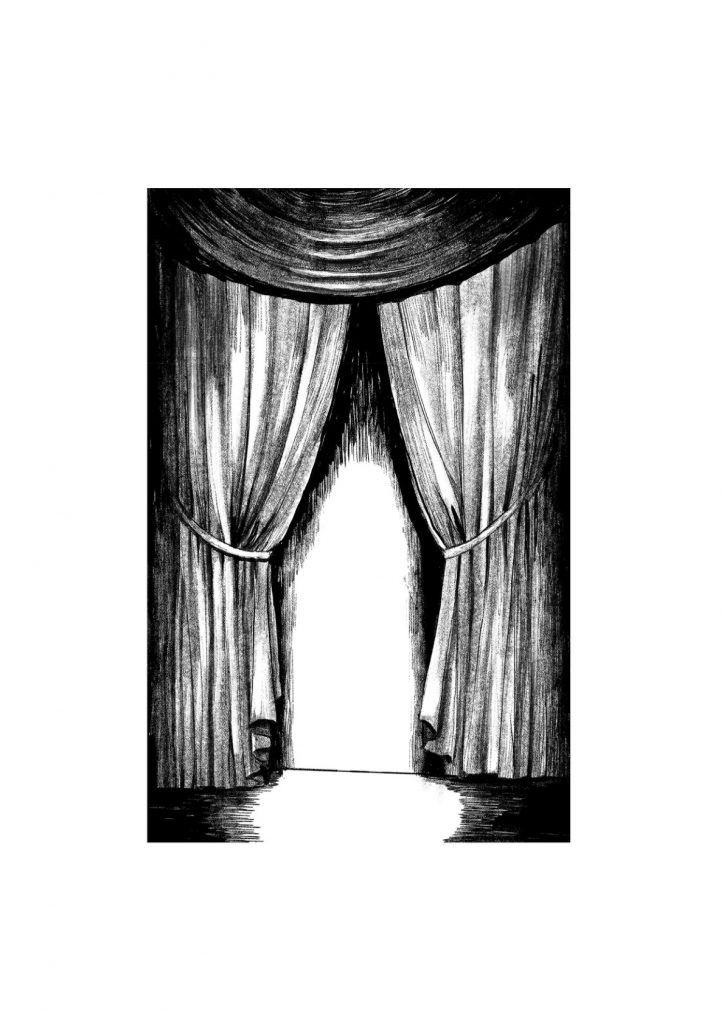

The presentation of the comic is defined in great part by its spatial sparsity: by opting for an uninterrupted sequence of one-panel pages using the exact same vantage point, the only thing that changes on the page is the movements of the star herself. As an extension of this rigidity, Cha not only chooses the same viewing angle for the whole comic, but also opts not to digitally redraw Rose Marie’s surroundings, meaning that while Rose Marie dances around her not a single line stirs out of place (and those surroundings—the sparse stage, the curtains—are rendered so totally that they could be mistaken for a manipulated and filtered photo, assisting that sense of the twilight of the real). What may well be a simple time-saving decision takes on an elevated function, depicting a stillness and stiffness in the world around Rose Marie. The comic, then, achieves a sort of pure temporality: the page represents the stage, but through its spatial immobilization it becomes a form of cage (if you’ll forgive the unintended repeated rhyme).

Similarly, by “anchoring” the comic to an existing song and the song’s units (the lines) into the units of the comic (the pages), Cha disambiguates the temporal boundaries in a way not frequently seen in comics: you can dwell on a page for hours, but your pace of reading will do nothing to affect the pace of the story by even a millisecond, as the chronological length of each page is measured and recorded. And not a single thing extends past those temporal boundaries: the comic starts as soon as the song starts and ends as soon as the final note is played. If, as the inside front cover announces, “Baby Rose Marie – Blue Bird child prodigy can’t stop Singing The Blues” [sic], it is not because she chooses to do so—it is because her entire existence is defined by it, and the end of the song brings with it, as we’ve seen, a complete and total decoherence.

Because of these anchoring visual, spatial, and temporal constraints, Baby Rose Marie the Child Wonder Sings ‘Come Out, Come Out’ is a decidedly anti-narrative comic. To be sure, it is certainly not an abstract comic, insofar as its terms of formal play are articulated and visualized entirely clearly, and events patently happen on the page, but they are not tied together in any conventional way, and they refuse to remark on each other or be remarked on: the comic is a pure temporal motion of decay, apathetic to its readers or its inhabitants. It raises questions that it has no interest in answering, because answering them would be anathema to its very existence.

This anti-narrative drive is what sets apart the comic from standard “horror”: it refuses to engage in conventional narrative-structural aspects such as stakes or resolutions and presents its increasingly gruesome events in an even, almost frustratingly neutral and alien manner, demonstrating a different intent than to simply evoke or remark on fear or unheimlichkeit. Indeed, under this anti-narrativism, horror transforms into a sort of tragedy: we are shown this deformed, uncomfortable monstrosity, which we are conditioned to fear, but instead of any act meant to justify our fears, it simply… sings. It sings and sings until it can barely take it, until it can’t go on any longer. We see something that is not seeking to harm us; on the contrary, it harms itself for our entertainment, and one can only assume, given what little bits of context we are given in that inside-front-cover announcement, that this is neither the first time nor the last that Rose Marie has gone through this pain, given her popularity.

This strikes me as the real monstrosity, the real horror at the core of the comic: that moment of boxing in, in which the performer is popular enough that they are allowed to be nothing beyond the confines of the performance, forcing them to be both the projection screen and the work being projected. This is the moment when any semblance of truth is robbed from the performance, and nothing remains but the suffering of the simulacrum. In this way, I was reminded of the “Club Silencio” sequence in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, in which, after a monologue in which a magician emphasizes that everything is an illusion including the live music played in the club, Rebekah del Rio sings a Spanish rendition of Roy Orbison’s “Crying,” only to die mid-song—while the music itself keeps playing, independent of its ostensible singer. In Cha’s comic, similarly, the humanity behind the song might be long gone—but its performance will keep the rotting flesh alive forever.

It would be tempting to consider Jenna Cha’s minicomic alongside others that similarly employ an ersatz-nostalgic (or at least heavily referential) aesthetic, be it through direct named parody such as Johnny Ryan’s The Comic Book Holocaust or through blatant stylistic stand-ins like Al Columbia’s Pim and Francie or Massimo Mattioli’s Squeak the Mouse, but it is this tragic empathy that sets it apart from the aforementioned peers. Whereas those creators veer into the territory of edgy provocation that at its worst declares “The past sucks because it is the past and it sucks!” and, at its best, at least attempts to engage with the regressive conservative dialectic that stands behind the smoothed-out wholesome-clean aesthetic, Cha trades the provocation for an empathetic nuance that considers not just history’s tendency to wash out its own immoral stains but also those who were caught in the wake of that wash; whereas others tend to look at history as this collection of aggressors, Cha’s comic takes the emotionally-logical next step and considers their victims as well. I do think there is a merit in the condemnation of those aggressors, of course, especially in a form like comics whose love-hate relationship with regulated nostalgic respectability is well-documented (both historically in the form of the Comics Code Authority and in the present day in the worship of the nigh-Sisyphean stagnancy of commercialized intellectual property), but Cha, in her attempt to spotlight the complementary flipside of those aggressions, has a far stronger emotional mooring and resonance.

It would be tempting, too, to frame this tragic element of the comic as a sort of treatise on the futility of separating the art from the artist—in that, by expecting the artist to be “just” the art without a personal dialectical agenda guiding them, you are effectively turning them into a subhuman creature singing and dancing for your entertainment—but I think this would be reductive to Cha’s intent. By choosing the art of a bygone era (not better, not worse, just different and long-gone), Baby Rose Marie the Child Wonder Sings ‘Come Out, Come Out’ warns the reader against reductive, category-driven thinking: it employs an aesthetic reference to beg the reader to look beyond the confines of referential shorthand, to look at Rose Marie not just through the lens of the child performer and at the work being performed not just through the lens of naïve nostalgia. When that fails, the book tries a different plan of attack: it chooses to lead us, soberly and evenly, to the dehumanizing, painful consequences.

In 2022 none of my grandparents are alive. They all emigrated to Israel, and they all, at their own pace, passed away. Some lived longer than others; some did not get to see the fullness of the large families they helped found. Baby Rose Marie, too, became “baby” no longer, living for a total of 94 years (a whopping 91 of which she spent, to some degree, performing) before dying in 2017. But 1933—the year that “Come Out, Come Out,” well, came out—is, to me, inaccessible: I have minimal ties that go that far back into my family’s (and, by proxy, my own) past. It is, then, unspeakably difficult for me to think of it as anything other than the distant past. The more I think about it, the more struck I am by the lack of imagination in L.P. Hartley’s statement that “the past is a foreign country”—it is far less accessible in any real way, untouched by that fish-eye lens of hindsight. Jenna Cha’s minicomic, then, is a shock to my chronological system: harrowing in its empathy and total in its grasp, Baby Rose Marie the Child Wonder Sings ‘Come Out, Come Out’ travels back in heartbreakingly precocious hops and skips, leading the reader by the hand and saying: “A foreign country? The fullness of the past—the fullness of me—is just around the corner.”

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply