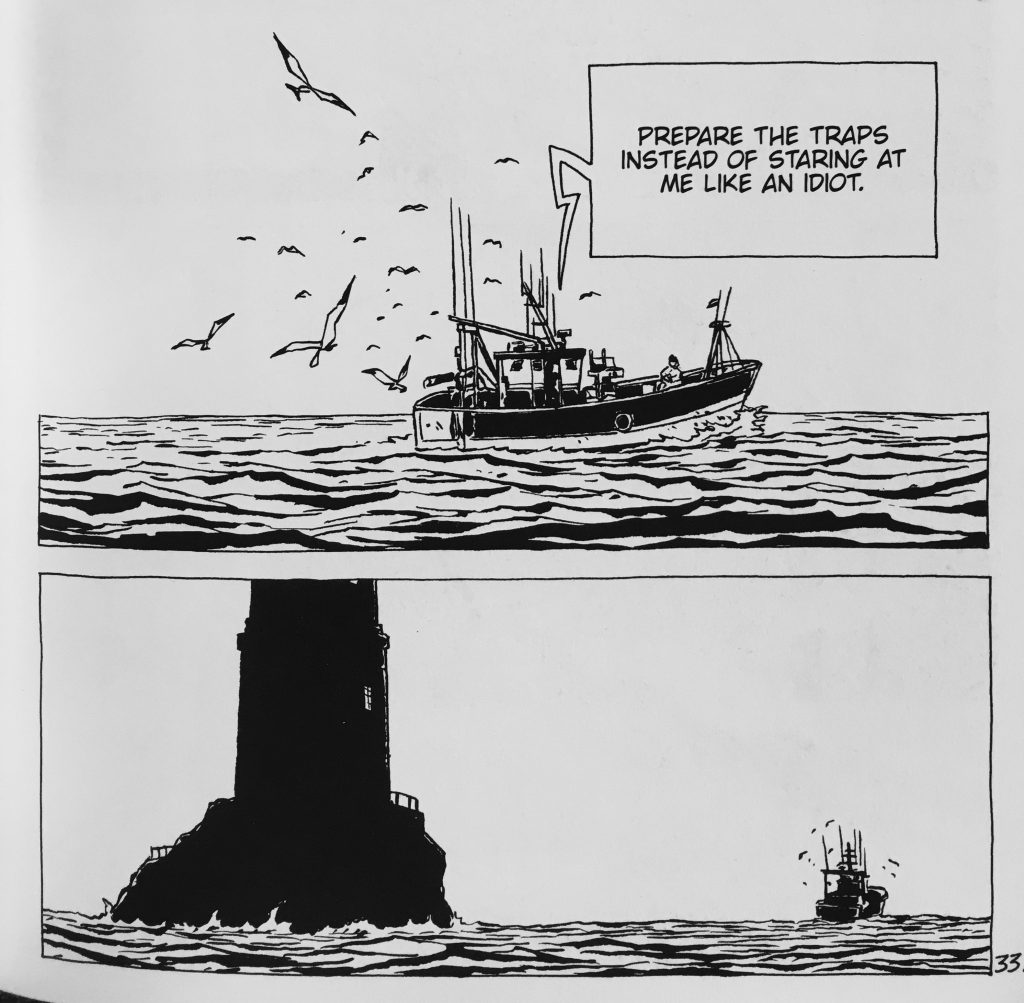

‘Alone’ by Christophe Chabouté is an empathic work that concerns itself with solitude, imagination and how these can shape a life. The protagonist of the mostly wordless story was born on and has never left the lighthouse he calls home. No one knows his name, they just call him ‘Alone’. His parents died but before his passing, Alone’s father gives his life savings to a surly but honest fisherman and extracts a promise from the grizzled sailor to deliver food to his boy once a week.

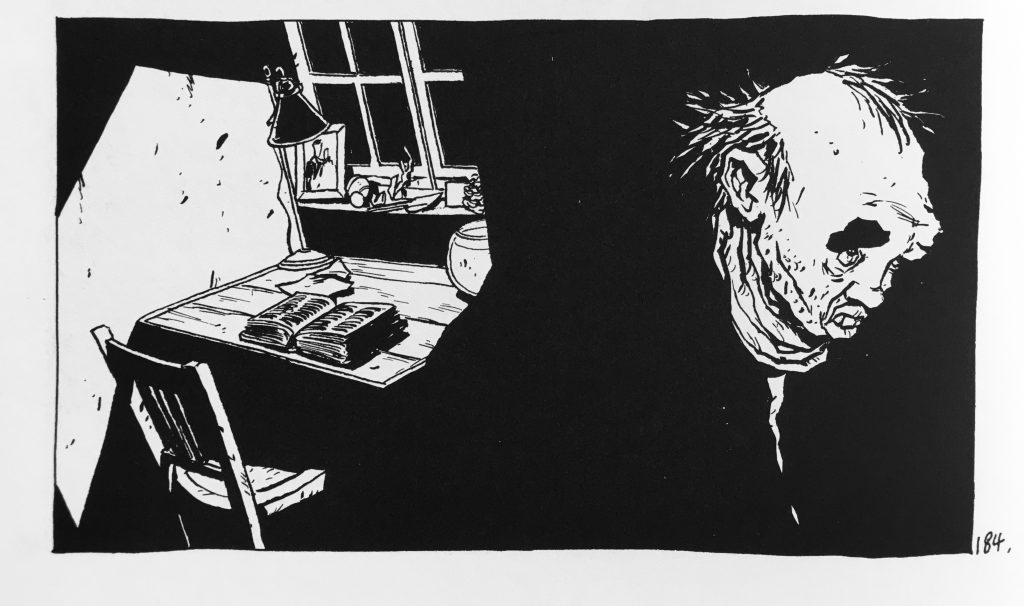

The reader doesn’t meet Alone until a hundred pages along. Aside from the occasional long distance frame where Alone appears in silhouette, the first time we meet him is a testament to Chabouté’s skill as a storyteller. The first encounter is a tight close up of Alone’s misshapen eyes in what must rank as one of the smartest uses of a page-turn moment in comics. We spend two panels examining our protagonist’s face and then he’s gone, a silhouette again.

Neither Alone nor the fisherman attempt to make contact with each other and the arrangement continues for more than fifteen years. Alone hides in the lighthouse until the boat pulls away each week, shambling down to collect his boxes of food.

His only link to the outside world is a battered dictionary. Alone can read but cannot always understand what he reads, nor does he have experience as a guide. The crux of the book is a note left by a new fisherman asking if there’s anything from the outside world that Alone would like. This offer of something from the world other than food triggers Alone’s awakening.

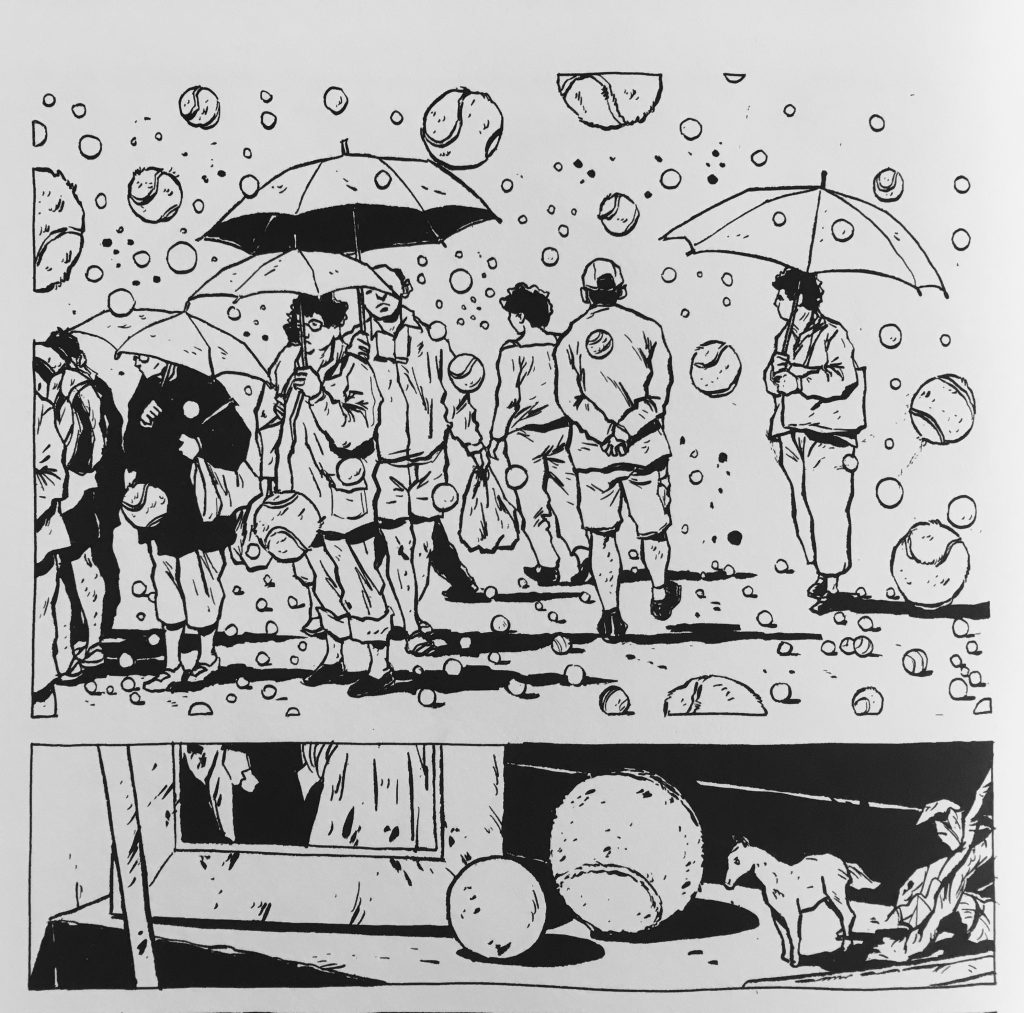

Chabouté invites the reader to spend a few weeks with Alone, observing the patterns of his life and the varied imaginings sparked by his daily dictionary readings. Each day Alone opens the dictionary to a random page, closes his eyes and points to a random word. Then, using the definition provided he imagines what the word must mean. Often Alone’s visions are comically misaligned with reality (‘podiatry’ in particular is very funny); at other times Chabouté is painfully heavy-handed (‘monster’).

Chabouté pays close attention to each encounter Alone has, including the non-human (a rapacious flock of gulls; a pet goldfish) as well as the non-living (the lighthouse; the dictionary; the fisherman’s boat). His gaze is unflinching. He finds the hard truth in people’s faces and actions but tempers this in his portrayal of Alone as a lonesome grotesque with a tender, curious spirit.

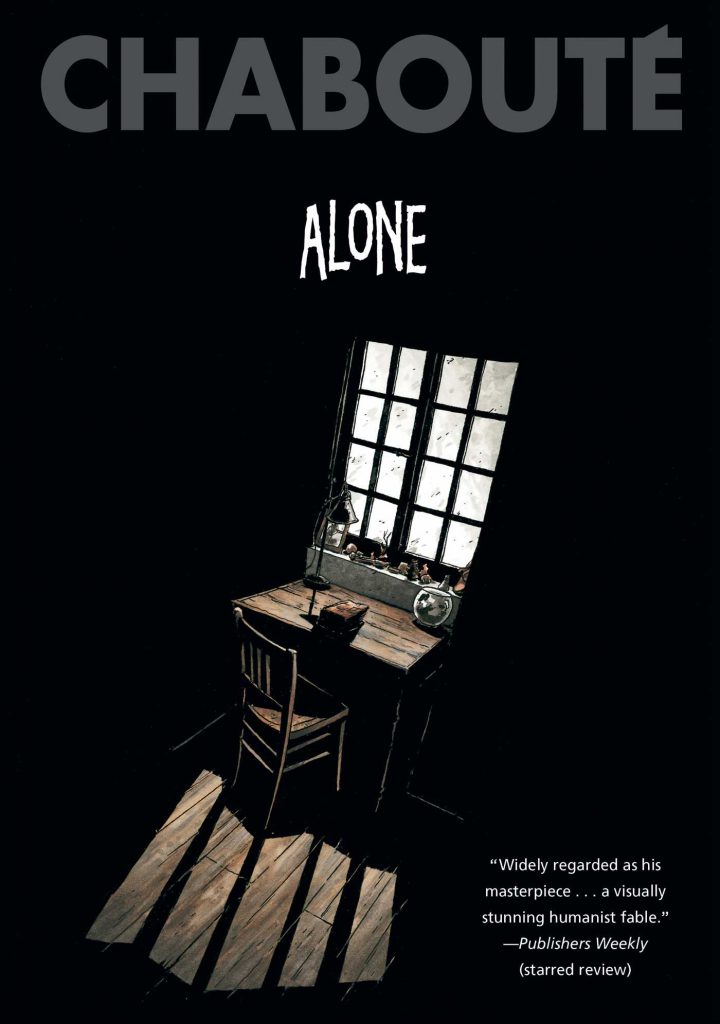

Alone lives an ordered life. His routine consists of fishing, reading, talking to his pet goldfish, receiving food drops and imagining the outside world. There is something ritualistic in the way he approaches these activities, especially the reading. Alone’s desk is empty excepting the dictionary, a fishbowl and a small lamp. The dictionary is centered on the desk.

Facing the desk is a window adorned with objects from his past and objects from land, brought to him by the sea – the branch of a tree, a shuttlecock, a pinecone, a tennis ball. This is a place for study and reflection. A place of spiritual significance. He uses a single sacrament – his dictionary– to trigger imaginative visions. Like all religious visions these are intense and often confusing.

His attempts at imagining his way to knowledge begin humorously – his dictionary doesn’t specify the size of confetti so he imagines them as dinner plate-sized paper circles flung by partygoers. The entries for ‘mushroom’ and ‘oboe’ is charmingly warped.

As the story progresses some imaginings take a bleaker turn when Alone chances onto words like ‘monotony’, ‘prison’ and ‘solitude’. These three words in particular are bolstered by Chabouté’s use of white space.

Individual scenes in the book flow narratively but often not visually. Chabouté uses a single white page to bracket scenes and this has the effect of turning each scene into its own discrete episode – something linked to but separate to the scene following it. These carefully located white pages come to define the pace of the book. We are invited to consider each episode, pause and then read the next. The pause is important – it reflects the measured pace of the protagonist’s life.

Chabouté’s command of white space and its effect are heightened by his treatment of shadows. The lighting in the story is always stark, the blacks are dense and unforgiving. There is a pervading sense of staring unflinchingly at reality – something Alone has yet to do.

The blank page that separates episodes is heightened by the liberal use of white space in individual panels. These merge together creating a sense of space, but also a sickening sense of being penned in by a featureless expanse. Seen this way we begin to sympathise with Alone’s plight. Yes, he has the sky and the sea and boundless space but without detail but these spaces may as well be the walls of a prison. For the most part Chabouté eschews clouds in daytime – the nights are starless so maybe that’s when the clouds appear. At either time of day, the sky becomes an enemy with no end.

Chabouté builds walls for the other characters, too – the fishermen are kept apart by mutual distrust; the couple on the yacht are prisoners of their relationship; Alone’s goldfish lives by itself in a fishbowl bereft of foliage or cover. Only the ever-present gulls have companionship and Chabouté portrays them as an aggressive flock composed of goggle-eyed, insane predators.

All of these beings are linked and bound by Chabouté’s use of white space – the feeling of a big, blank prison. This makes Alone’s empathic qualities all the more remarkable as the only source of warmth in the book. From sharp white paper to jagged line work to stark lighting – Alone’s whole world seems set sharply against him. When he apologises to his goldfish and then hides his fish dinner to spare his pet’s feelings, this kindness makes the story sing.

Chabouté s depiction of Alone’s imaginings uses a trick comics are uniquely suited to – hiding the line between reality and unreality. Movies are getting better at this but for the most part a viewer can still pick out CGI shots. Comics mastered this transition at its inception and Alone’s imaginings flow seamlessly between real life and the world in his mind.

By not providing a visual cue that we are about to enter Alone’s mind, Chabouté may well be commenting on the nature of imagination – how our minds incorporate aspects of the real world into dreams or into acts of creation. In some cases we are given visual cues (Alone’s finger pointing at an entry in the book) but the story surprises as disparate imaginings begin to interact: the subject of ‘butterfly’ flaps lazily into the subject of ‘battle’ and the soldiers are taken aback. We are being shown a character’s mind at work and comics as a form being used gracefully.

In this context, it is worth considering Chabouté’s line work. He favours a thick line, sharp corners and a jagged stroke. It plays strangely when he draws rounded shapes –even water droplets have corners. The sharpness of the line lends a strange clarity to his images, as if they were a collection of photographs. Panels in comics freeze time but Chabouté takes the extra step in how he chooses his moment-to-moment panel transitions, creating a distance between reader and character. This, coupled with his use of white space finely controls the reading experience.

‘Alone’ is an incredible act of storytelling by an artist in his prime. The reading experience is marred by only one aspect – the book design. An oddly thick paper stock makes page turning cumbersome and it doesn’t help that the choice of binding is weird – who chooses to perfect-bind a 370-page book, especially one that needs to withstand repeated readings? Perfect-binding (a thin coat of glue holding individual pages together) is an unwise design choice if you’re trying to bind so many pages. My copy now has pages falling out and the spine cracked long ago in unpleasant ways. If there’s a hardcover of Alone available, buy that instead. On a positive note, the cover design is haunting and lovely and the type design of the accent aigu on ‘Chabouté’ is subtle and clever.

Grumbles about book construction aside, ‘Alone’ is an elegant, challenging story that rewards rereading. Chabouté invites us to grapple with the idea that unless someone intervenes, loneliness is inescapable. Without intervention we would be lonely until death. At the same time he suggests that we live well only through interaction, community and communion with other humans.

Chabouté addresses also the divide between imagination and experience. First hinted at in the epigraph to the book (presented as a dictionary definition of ‘imagination’) he seems to suggest that a rich, well-lived life demands experience more than imagination. That without experiential context the mind can only fathom so much of reality before it peters out into madness.

This is an uncomfortable view but feels true to the story in a stark, unflinching way. Alone’s life in the lighthouse is by turns amusing and heartening for the reader, but from the character’s point of view it is something altogether smaller and darker. To grow as a person, Alone needs the experience of the outside world more than he benefits from his imaginings of it. Once he comes to yearn for experience, to grasp at it, his life begins to change. For better or worse is uncertain, as in all our lives.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply