On a shipwreck never sinking, two lovers drift apart together. They had formed a pact, founded on fowl dismemberment, sealed with a kiss, to be consummated in the new world. They will never arrive. Set adrift, the journey ferments in the cruel light of the sun, the vessel itself rots, the gnarled wood of the walls growing seasick, sweating saltwater and moldy brine. Leonora is helpless, her skin dried in rings around her skeletal face, as she bears witness to her beloved Ursula consumed by the sweltering decay she too suffers. Each knows the other to be responsible for this grief. Each knows just as well their own culpability. Their choice. Drunk with the hope of another place, another potential, they had sinned, and their sin is justly punished with an eternal, damned journey, stripped of destination.

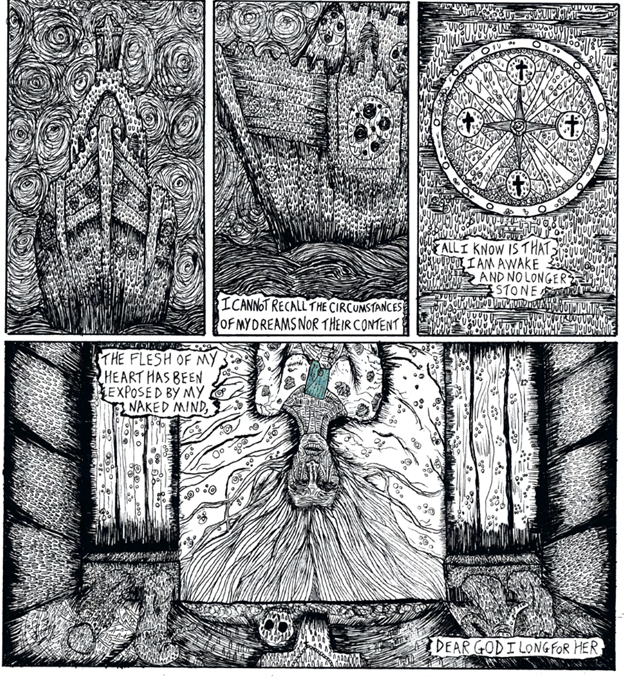

Ursula is an intimate, seasick gothic horror romance of undead witch lesbians in purgatory from writer Lane Yates and artist Erika Price, an obsessively realized descent into agonizing tapestries of decay, festering affection, and earned punishment. The comic continues Price’s preoccupation with expressing transfeminine gender dysphoria as a horror premise and aesthetic, women in agony whose skeletons yearn to push out of decrepit skin, doomed to bodies too large, too frail, too rotten, forced to live an existence more like death than life. Her pages are overwhelmed with graphic detail like serrated cuticles of drying skin: the hull of Ursula’s ship is filthy with infinite layers of skulls and dripping leaks, her figures so worn and decomposed that every part of them seems on the verge of being torn to pieces, down to the hair, the teeth. Even the slight splashes of color introduced are sickening, a mottled watercolor sea-green like the cursed ocean or rotten flesh signaling the ghostly presence of Leonora, Ursula’s bitter love. But whereas Price’s prior works have largely been about isolation, suffering alone in elaborate torture chambers that penetrate the body, her collaboration with Yates on Ursula introduces a different kind of hell where one does not suffer alone but together. The lovers are damned and cannot leave each other alone, they bear witness to each other’s pain. Nobody is ever left alone in Ursula, not even with each other – a skeletal, ghoulishly stubborn fellow traveler is never far away with horrendously absurd, restless mundane preoccupations to busy themselves along with everyone else, tireless efforts to wear down the captive travelers with duties long rendered pointless, no world remaining for obligations to bear fruit.

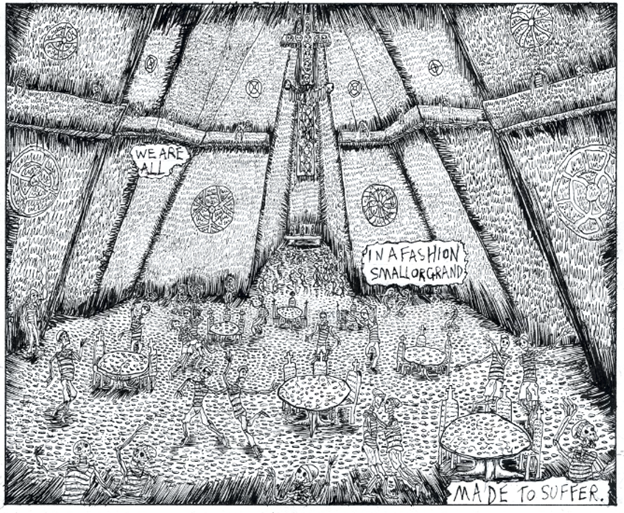

While Erika Price’s comics to this point have been about decay, gradual, agonizing systems of destruction that hold her tormented victims in stasis, waiting for their pain to come to an end that never arrives, Lane Yates’ webcomics and zines have been about stages of rot as well, in a sense, her lens trained on the absurd bickering of couples and roommates in a world too drab to fulfill their desires, deadpan satires dressed in a peculiarly haunted tenderness. Yates brings a new dimension of agony to Price’s graphic horror — her suffering heroines must endure another torture as their skin peels away, the torture of being accompanied by irritating people. There is seemingly no end to the shuffling of chairs aboard Ursula‘s unsunken shipwreck — walking skeletons carry on about dinner parties and important meetings, social niceties exhaustingly repeated to nauseating ad nauseam. Grudges are kept, neither resolving nor exploding, but simmering pathetically, a punishing performance with no reward. Hell isn’t other people, it’s watching your flesh and everyone else’s flesh gradually flake off in a moldy seasick labyrinth of death while also stuck with other people.

The hell of Ursula is a lesbianism without possibility or privacy, a loveless, sickening curse, a brutal punishment that knows no mercy, pleasure, or beauty. These living dead girls will never again experience softness or kindness; the joy of sapphism has been torn from them by the Virgin. But on some level, isn’t this the sapphic fantasy? Ursula and Leonora have rejected everything for each other. The new world they would reach would be one of danger, exploitation, the budding violence of colonialism – in their endless, stranded hell, they aren’t hurting anyone else, really.

We all suffer. Wouldn’t it be nice to know that your suffering will never end? That you won’t suffer alone, but with a lover who suffers just as much? Wouldn’t it be nice to abandon all hope and be free of the wearing expectation that things might get better if we try to be different? Wouldn’t it be nice to know God hates you and never have to wonder again? Wouldn’t it be nice to love someone and have nothing else at all?

With Ursula, Yates and Price offer a defiant, queer lament, bemoaning a world where love and personhood are crushed under the weight of social obligations and sadistically closing off all possible avenues of escape. In these shattered, angry pages, we are still reminded of the queerest dream, to love someone and get away, to care for each other and safely lick our wounds, even if it involves going to hell. But in hell, this hell, our hell, queers are never really alone with each other; new wounds open where old cuts seal, our tenderest moments will be torn asunder by the most torturous interruptions. But a nightmare is still a dream – readers will cherish Ursula and Leonore’s love, even as their all-too-familiar torment consumes them.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply