How do you publish and distribute comics during a pandemic? It seems like a Herculean task, to say the least. And yet, there are plenty of small press publishers out there doing just that, right now. One of these publishers is BEEHIVE BOOKS.

Beehive Books is a small press imprint in Philidelphia founded by artist and designer Maëlle Doliveux and writer and editor Josh O’Neill, formerly of Locust Moon Press. They are a boutique company committed to producing book art editions of distinctive literary and pictorial works with singular design sensibilities, the highest production values, and a special emphasis on comics and graphic art.

You can find out more about Beehive Books by visiting their website or by following them on Twitter or Instagram. I thought I’d send Josh O’Neill and Maëlle Doliveux some questions about what publishing is like in these strange times, and they were kind enough to answer

Out of all the things you could possibly be doing with your time, you all decided to publish comics. Why is that?

JOSH O’NEILL: Because cartoon production is an essential human activity, and may well be necessary to the survival of the species.

Which is not to imply that there’s anything grandiose about what we’re doing — we’re just another publishing company doing their best to weave some crooked path through personal tastes, economic realities, and cultural tides. But the general work of publishing comics and art, of creating economic frameworks that allow authors and artists to spend their days making new work, and open avenues of access and readership to those works, seems genuinely indispensable to me. As long as there have been people, those people have been making cartoons and artworks, telling stories, trying to understand the world around them by reflecting and transforming it. And as long as we’ve lived under capitalism, there’s been a need for networks of businesses and collectives to materially sustain the process of art production.

But market-based mechanisms can be actively antagonistic to the kinds of work that we need to survive and thrive. A career as a graphic storyteller is a brutal and frightening prospect for most people. We’re trying to build sustainable mechanisms by which we and the artists, designers, editors, and press workers can both (a) make work that they find meaningful and exciting and useful and (b) afford to buy Pop-Tarts and shampoo and health care. We try to think critically about existing business models and who they serve in order to build better ones — models that serve those who labor within them, and are capable of enduring the challenges and depredations of art production in the anthropocene. Our success thus far has been limited, but we feel a genuine urgency about this attempt and our project. We’re not done trying.

How has the world of comics publishing been impacted by the pandemic?

JO: I don’t think I have enough of a bird’s-eye view to answer this question accurately. Beehive inhabits its own strange little corner of comics and arts publishing, with a small but consistent audience, so we sort of operate somewhat independent of the larger industries within which we exist. Now that we can’t go to comics conventions and book festivals, we feel even more unplugged than usual from the big publishing picture.

I do know that this has largely been a pretty brutal time for a lot of publishers. There are a number that have folded entirely, and a lot more hanging on by their fingernails. We were very lucky — by total happenstance, our direct-to-consumer crowd-funded business model slots pretty nicely into the pandemic lifestyle. We’re distributed in bookstores, but our lifeblood is direct orders and Kickstarter pledges. It feels ghoulish to say, but the pandemic has been an economic boon for us. People are reading more than ever, now that there’s so little else to do. One of our company taglines is “we build paper worlds.” Now that the actual world is largely verboten, paper worlds may have more appeal than before.

I do think for all the economic calamity brought upon artists, authors, and publishers during this nightmare, it’s also probably hurried a lot of folks down avenues they were eventually going to need to walk anyhow. The demand for books and comics has been growing for quite a while now, and in the past year it’s spiking. But the old industries of the book trade and the direct market are problematic and sickly at best. It’s incumbent on those of us in the book business to find faster, better, more sustainable ways to get the work out into the world. My hope is that a lot of creative folks have used this time to create and strengthen new distribution pipelines that will continue to benefit them long after COVID is in the rear view mirror.

What would you say is the ethos of Beehive Books? Are there particular types of books you look to publish?

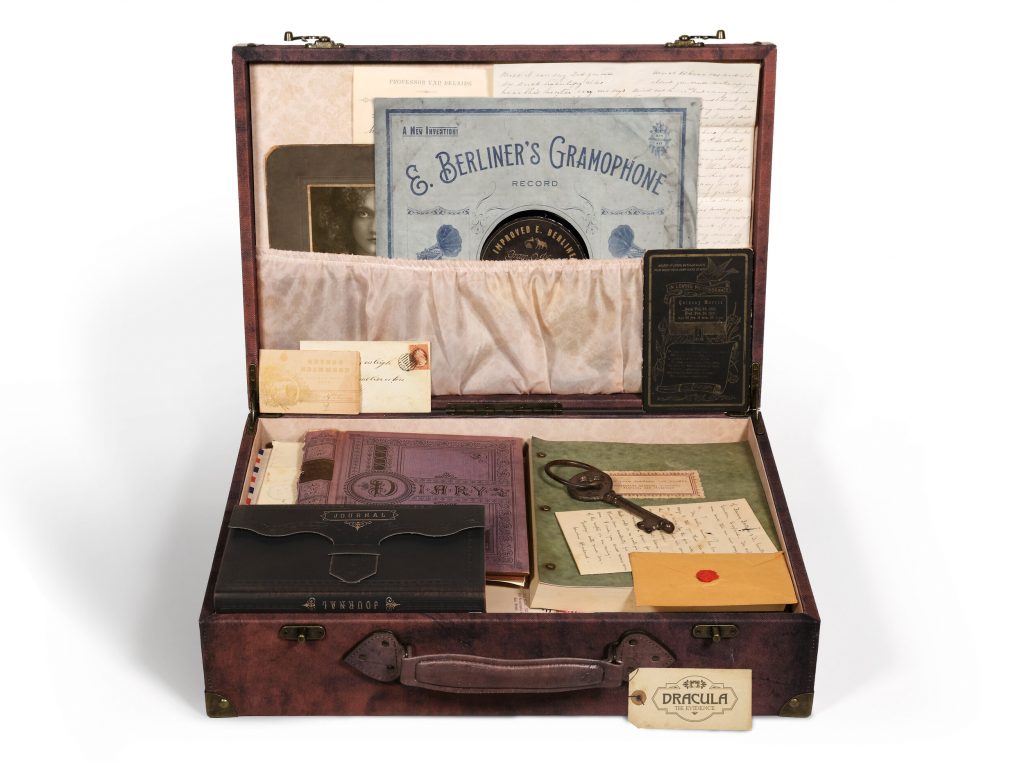

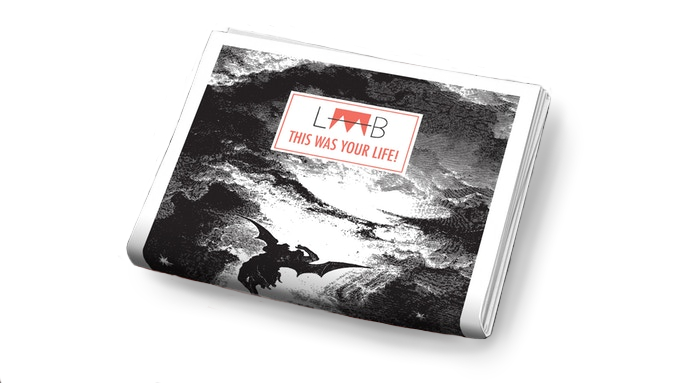

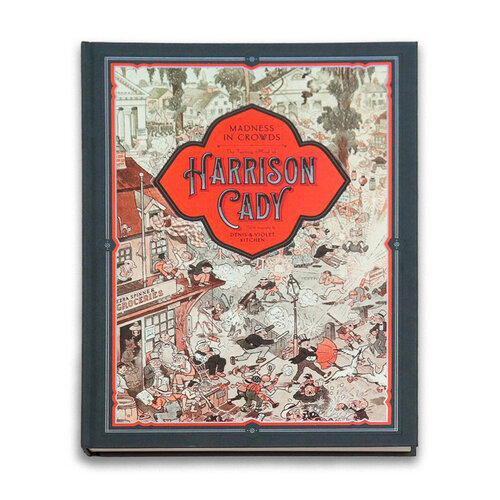

Maëlle Doliveux: Anything extraordinary, beautiful, and a little too special for traditional publishing. Our goal is to make beautiful art, illustration, and comic projects that aren’t forced to adhere to mass market restrictions, like bookstore shelf sizes, or bulk pricing, or market studies. We want to work with artists and for artists to dream big, push what is possible in publishing, and make projects that stand out. If you have a beautiful book project that you think will never get made, we’re probably the people to talk to.

What is it like working on major projects during the COVID-19 pandemic? Has anything changed about your process or your planning?

MD: In all honesty, we’ve been extremely fortunate that the pandemic has, for the most part, been limited in its impact on how we work. Josh lives and works in Philadelphia, but I (Maëlle) am New York City based, so we were already familiar with working remotely (through Slack mainly) before all of this started, and used to video meetings and all that. Obviously, the greatest impact for us has been in a slow down in our fulfillment and to some extent, our production. Restrictions have meant that fewer people can work in warehouses at a time, and our very understanding customers have been patient with us as it takes a little longer to get them their books. We’ve also learned in the last year to be better about scheduling more ‘just in case’ time, to allow for inevitable hiccups, rather than trying to adhere to a ‘best case scenario’ schedule. Obviously, we don’t hope for (or foresee) another world event as traumatic as what happened last March, but things always come up, and we’re only human after all!

One of the professional changes that we’ve regretted the most has been the loss of conventions! It was always such a wonderful way to get to meet our readers, and meet new like-minded people and artists we’d like to work with. And also a great place to celebrate projects once they were completed! We really look forward to pitching up a convention table again (this time laden with at least an extra year’s worth of projects for which we’ll have to make room)!

How do you all find the people you work with? Do you offer mentoring or other services to those people?

MD: It’s a real mix of different ways! Some people are artists that we’ve worked with on other projects before starting Beehive, some we’ve met at conventions, some people are introduced to us through our previous contributors, sometimes we ‘cold call’ collaborators, and other times they reach out to us. We’re always open to meeting new people to work with, and we can be reached through our website. If illustrators are looking to reach out to us, it’s usually a bit clearer for us if they reach out to us with a specific project in mind rather than just sending a general portfolio, but we’re open to both.

Unfortunately, as there’s really just the two of us for the time being, we’re not offering mentorships right now. It’s something we’re open to down the line though!

Are you considering inequities or other historical considerations (for example, working with cartoonists of color and LGBTQ+ cartoonists) as you determine your publishing slate?

JO: That’s such a complicated question, and I don’t feel entirely equipped to answer it, though publishers are definitely the ones who must be asked. It’s something we talk about a lot in our internal processes and an area in which we’ve been disappointed in our own failures.

Speaking only for myself: I look at our publishing choices less as a way of addressing historical inequities than I do as part of the mission of art making, which in my mind is to reflect, explore and transform the experience of being alive.

The history of paid comics and illustration is dominantly white, male, cisgendered, able-bodied, and heterosexual. This has had a horribly cloistering effect on the art that’s been produced in these fields, effectively stunting the growth of the mediums, while further marginalizing people who were denied access to these careers and platforms. The historical inequities are not only antagonistic to justice — they’re antagonistic to art.

There’s a lot of energy now around the efforts to transform this history, and that energy is long overdue. But I’m also critical of exactly how the discourse around this issue often plays out. The problem is often framed as one of statistics and group representation.

What strikes me as more important than finding authors and artists that are “diverse” according to surface-level identity coordinates (race/gender/etc) is finding artists who are truly radically diverse in terms of life experience, background, social status, the communities they come from — the fundamental truths of who they actually are. I think we need art from sex workers, survivors of police violence and domestic violence, the housing-insecure, refugees, people who have undergone gender transitions, lived through wars, been incarcerated, folks with physical and mental disabilities. I suppose that reads as a list of forms of trauma — but I mean it to include the voices that are so often excluded from the social worlds of art and publishing. What we need are contributors from outside of the realms in which we already move, and in which so much of the publishing and especially comics worlds also move. Not because this will be a balm to their oppression, or as a form of historical reparations, but because the mandates of adventurous art-making and truth-seeking demand that we hear from all of our brothers and sisters.

But when the rubber meets the road, we often see the opposite. For reasons both laudable and PR-driven, a lot of publishers are attempting to fix their diversity problem. But the easiest way to fix the optics is to look around the room for someone who you can plug into your slate to diversify it. But the biggest problem is the nature of the room itself, and who has access to that room. If we’re not going outside of the room, all we’re doing is tokenizing individual creatives who are probably more alike than unalike. That’s not diversity; it’s optics.

It seems important to think deeply and critically about what it means for one person to represent a group. In a world in which we have a new president touting a Black head of the CIA as a victory for racial justice, we have to understand that a simplistic approach to these things can do more harm than good. I recently read a great essay on this topic from Olúfémi O. Táíwò, which I highly recommend to anyone trying to think through the contradictions of these questions.

To be honest, I don’t think Beehive has done a great job on any of these fronts. We’re not in a position to talk about how these things should or shouldn’t be done. We need to do better, and we plan to in the future. Not out of the kindness of our hearts, but because it’s our job to produce the best books we can, and every failure to engender real diversity from our contributors makes our books less vital, beautiful, and useful.

Thanks so much for your time and your words. Any last thoughts you’d like to leave with?

MD: Thank you so much for inviting us to participate in this series! We hope people are inspired to pursue publishing their own projects on Kickstarter, or to maybe reach out to us! And most of all – wear your masks, practice social distancing, and stay safe out there so we can get back to seeing all your handsome lovely mugs in person at a future festival!

On a final, entirely self-serving note: if you’re a person with marketing experience in publishing looking for some part-time work with our very out-of-the-ordinary company, please reach out! We’re looking to hire!

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply