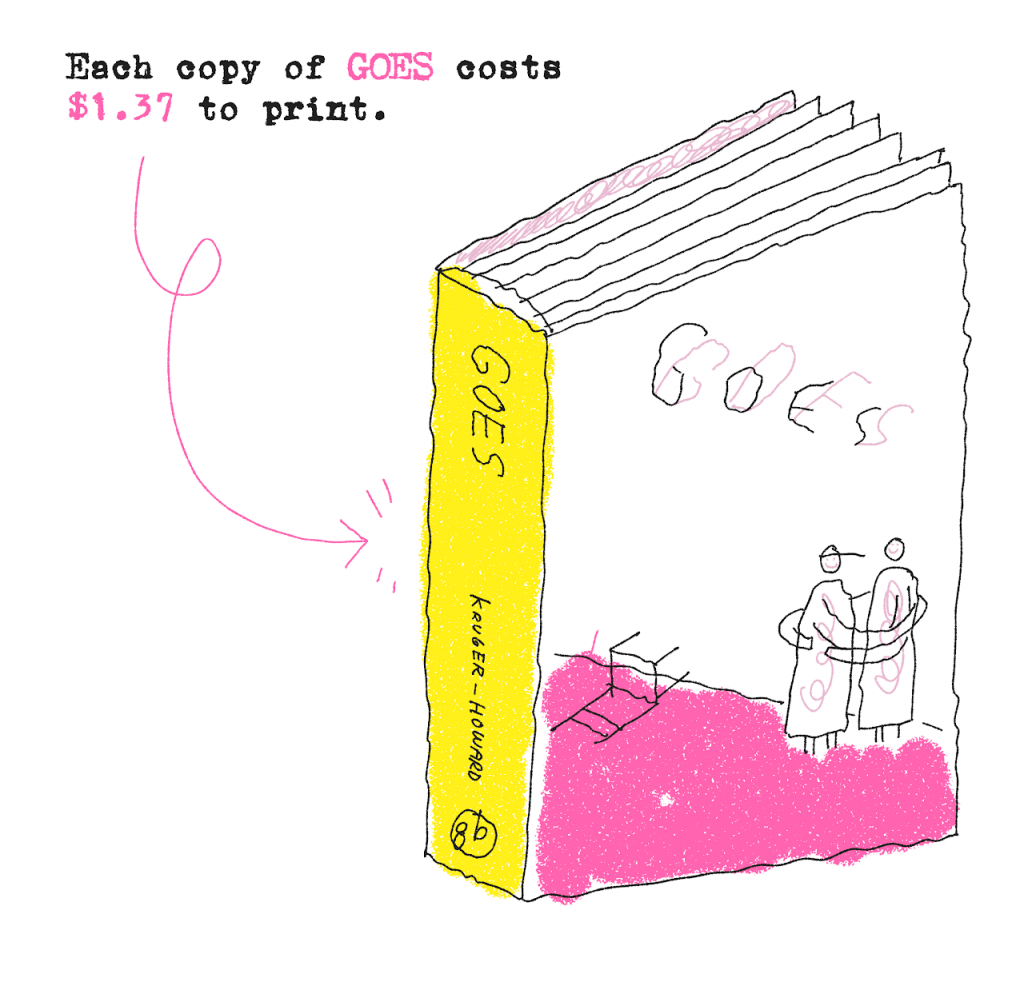

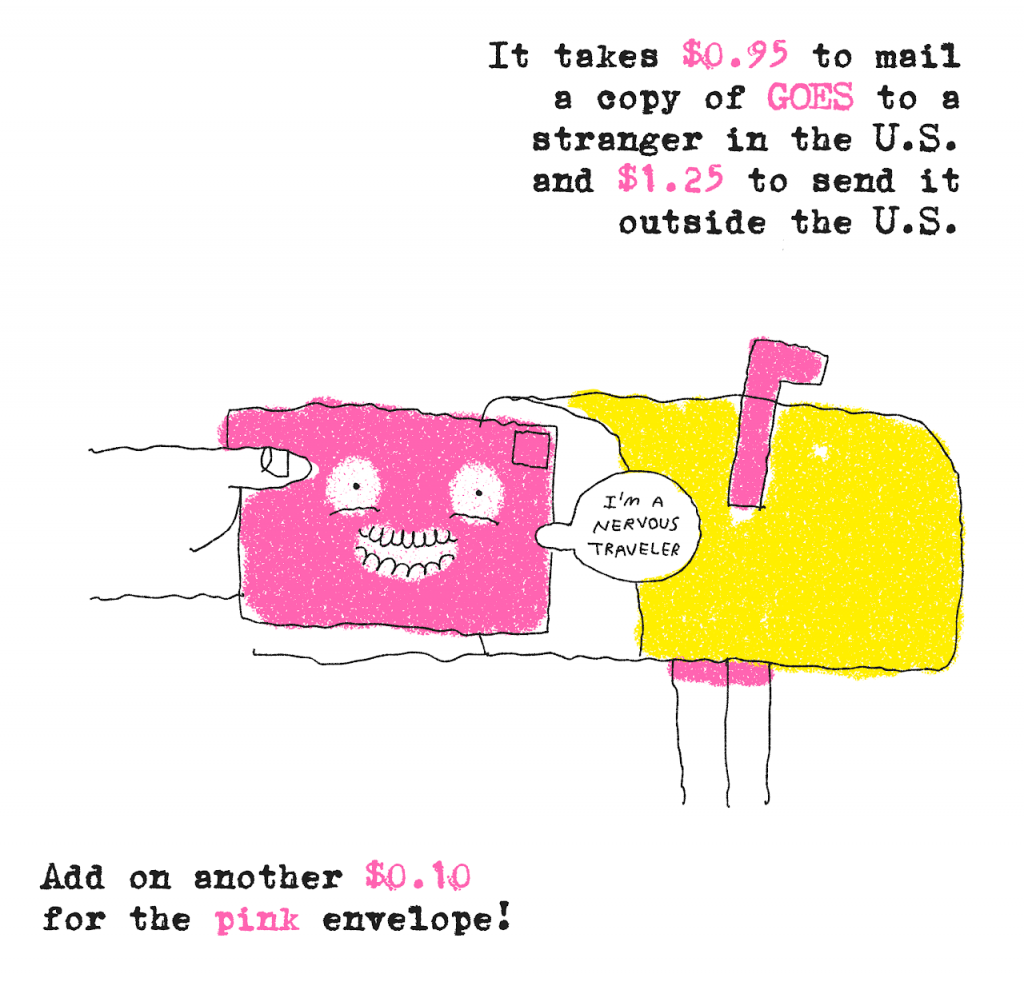

Luke Kruger-Howard’s new publishing venture, Goes Books, is an unusual one, even during this bizarre era of publishing during a pandemic. Kruger-Howard is publishing a new collection of his comics titled Goes, based on the theme of touch. However, he is intentionally circumventing not just the comics market in doing so, but the concept markets themselves. At the Goes website, interested parties can request a free copy of the book. Interested parties may also “pay it forward,” paying for copies of the book to go out for free. Kruger-Howard’s goal is to get the book into as many hands as possible instead of making a profit, and this is a deliberate part of his philosophy. This approach goes straight to the heart of his project, which is reevaluating the relationship between art and capitalism, as well as the concept of “emotional revenue.” Kruger-Howard was kind enough to answer some of SOLRAD’s questions about his bold new venture.

SOLRAD: Luke, how long have you been working on this project? That’s in terms of the comics you wrote for it, but I’m more interested in how long you’ve been planning your unique publishing model.

Luke Kruger-Howard: First, a fair warning to anyone reading this. I’m prepared to provide way too many opinions and rantings here because I’m very excited about this topic. Apologies ahead of time when your eyes start to bleed from exhaustion (and possibly from rolling too often)! Maybe I’ll pepper in some fun facts about butterflies along the way.

The comic Goes is a project that I started the week before my son was born – so end of May 2019. I was staring into the unknown of parenthood without any idea of what to expect. I knew specifically I was having a boy (or at least someone who in all likelihood will identify as a boy), and that started my head spinning in all sorts of different directions. I was thinking a lot about my own relationship with my father and wondering how the relationship with my son would compare and contrast. Would I behave differently with my child because of our common gender? Would that limit or skew our relationship in some way? Would we have trouble communicating? Would we be able to be physically affectionate with each other? Would we grow apart as time went on or grow alongside each other? (Can you tell I’m a worrier by nature?). All of these types of questions were brewing when I started the main story for Goes which is called Men’s Holding Group. But then my son Shepherd was born and the comic was joyfully shelved for well over a year. It was during that year and then during the pandemic, as a solo stay-at-home parent, with so much of my life being isolated away for 8-10 hours a day with a newborn, that I began fantasizing about the different forms that Goes might take. Eventually, that evolved into this micro-press experiment called Goes Books. I would say the press itself has been baking as a serious idea for just about a year now – beginning unsurprisingly almost exactly when we first went into quarantine here in New Hampshire.

Butterflies use their feet to taste things.

SOLRAD: What particular experiences as a working artist led you to want to publish in a non-profit fashion?

Luke Kruger-Howard: I just celebrated the 10 year anniversary of drawing my first comic, which means it has also been about 10 years since I started thinking obsessively about the different ways that comics have been and could be put into the world. It was also around that time that I became a student at the Center for Cartoon Studies, which means I was throwing myself into this very unique comics-making pressure cooker; 2 years making comics and thinking about comics at CCS is like 10 years anywhere else (at least it felt that way to me). This introduced me to the typical arenas that cartoonists use to disseminate their comics. I’ve done countless small press conventions over the years, hocked my self-published comics one bone-folded mini at a time, thrown my work into any anthology that would have me, tried my best to build an online presence, and had the honor of collaborating with some of my favorite small press publishers. Which is all to say I’ve had what feels like a very typical experience for the types of comics that I’m interested in making.

I also had the joy of being a teacher at CCS for over 6 years, which forced me to always be engaging with a young comics-making population that is constantly asking itself all those panicked and self-doubting questions about how to put comics into the world, where to put comics into the world, or even whether to put comics into the world. I consider that experience in particular, the gift of being around that student energy, an immeasurable benefit to my own practice. I’ve spent years now thinking about where the comics community could be better, where I think that community is strongest, dreaming about all the impractical possibilities out there that have yet to be explored, and all the ways I could “do things better next time.”

That’s all backstory that leads to this idea of a not-for-profit publishing model. Because I’ve had the privilege of dabbling in all these various forms of comics publishing, it has allowed me to see what works for me, and perhaps more importantly, what can frustrate me about these different forms (or even what can be at times toxic about them). One of my biggest frustrations personally has been the struggle to bring my comics into a money-making arena. The levels of shame and feelings of failure that abound when you’re trying to find a way for your comics to not only be something you’re proud of (which is a lifetime undertaking on its own), but to be profitable as well (which is in my experience a bit like trying to find the center of a giant labyrinth whose walls are constantly shifting around you). In a lot of ways, it’s a very narrow set of options that we as cartoonists have when it comes to publishing our work and I think there is a ton of unexplored territory out there. The not-for-profit model is an experiment in trying to explore some of that territory. Partially because it is a model I’ve never personally experienced before. But most importantly because I feel tuned-in to a lot of personal/creative suffering that is going on in our comics community right now – especially as it relates to the financial market. I wanted to try something that might examine some of the cracks I’m seeing in the foundation there. I think the overwhelming majority of comic artists feel like they are falling through those cracks and that’s a problem.

SOLRAD: What impact did being the primary caregiver for your child have on this project? What about living during the pandemic?

Luke Kruger-Howard: it’s interesting that these two questions are sitting right next to each other because I feel like both parenthood and the pandemic have been unavoidably transformative in the way that cataclysmic events are always transformative. It’s just strange that I had two such events happening on top of each other like this. I also think you would have to be some sort of superhuman to go through something like the pandemic and not have it dramatically shift who you are and what priorities you have. It’s worth mentioning that this period also came with the loss of my teaching position at CCS, in part because of our inability to afford childcare, in part also to the challenges of the pandemic itself, and because of the long-term unsustainability of my position there.

So I can’t deny that the last year and a half have been some of the most challenging, at times devastating, and somehow also the most beautiful I have ever experienced. I think anyone going through all that at once is bound to start asking themselves some hard questions and do some manic experimenting. The standard roadmap for what’s next in my career would be to try and get the next rung of publishers to want to work with me. So maybe that would be a mid-range publisher like Fantagraphics or Drawn & Quarterly. And if I check that box I suppose I then ought to try to move up to an even larger publisher like First Second or Random House. Then maybe I can get nominated for some of those prestigious comics awards I’ve always wanted. And then… you know, this has been the plan for so long now I kind of forget what the goal even is, or what I expect to happen if I ever got there…

So you see I’ve been trying to decide what I want the next 10 years of my comics-making life to look like and that has forced me to take a hard look at that standard roadmap and decide what about it works for me and what doesn’t.

Butterflies only live for a few weeks.

As far as parenting, even though it is the best thing I’ve ever done with my time, being a stay-at-home parent can make you feel incredibly invisible, especially in a country that measures value so often by what you contribute to the marketplace. And our small comics community is not immune to that problem. Our community has its own version of placing too much value in how well things perform in the marketplace as well as the idolization of constant content production. So even in this wonderful little community I belong to, parenting is a fantastic way to begin to feel invisible. As my friend and cartoonist Lucy Bellwood said to me recently, “there’s no line item for being a parent.” That feeling of invisibility was bringing up a lot of anger and frustration for me. Why was it that I could feel so rewarded by trying to keep a tiny human alive every day, and at the same time feel so much like a failure professionally? I think that is just an incredibly silly contradiction and it speaks to a glaring problem with how we learn to measure value and success.

I also think there was this terrible kind of perfect storm that went on over this last year with Trump, the pandemic, the BLM protests, the January 6th terrorist attack, and even crazy stuff like that Game Stop thing that really highlighted for all of us just how remarkably broken, imaginary, and downright dangerous most of the systems around us really are. We’re all feeling that, I suspect.

So all that mess had been slow-cooking in my brain and my heart over the last year and it was really what put me into a frame of mind where I felt like I wanted to try something ridiculous and impractical and unintuitive like Goes Books (wow, that sure was a long answer to your question).

SOLRAD: Did getting off the comics-show carousel during the pandemic provide any impetus for rethinking your approach to art?

Luke Kruger-Howard: Getting off that carousel did have its benefits, though I deeply value that part of our community and miss it a lot. Still, having time away from conventions does get you the space to ask yourself some bigger questions and test things out that you might otherwise not. When you’re in that yearly grind, always getting ready for that next convention, things can get a bit stuck. Who has time to build out a new project when you have to finish your latest mini-comic for TCAF (and then CAKE, and then MeCaf, and then SPX, and then MICE, and then…)?

SOLRAD: Was the pay-it-forward system of paying for printing and shipping something that you originated, or did you borrow it from another source? What kind of economic groundwork and research did you do before launching Goes?

Luke Kruger-Howard: I didn’t base the pay-it-forward system on anything in particular, but I think there are likely plenty of similar examples. Originally I had envisioned that I would completely fund each Goes Books printing venture by way of trying to track down larger donors who could part with some of their cash and in turn help us gift a bunch of books to people for free. But as the planning went on, there were two aspects of that approach that didn’t feel right. The first being that I didn’t like the top-down aspect of having these projects fully funded by one or two large donors (though I think wealthy people need to be giving way more of their money to the arts than they are). I wanted these books to feel like they were possible because of the actual people who were reading them. The second being that I wanted to use a system that felt communal. I like the pay-it-forward model because it changes the whole feeling of things. Instead of me acting like some sort of newsie out on the corner handing out free copies of Goes to every passerby, I would let folks who were interested in reading the comic also develop a personal investment in seeing that other people get to read it as well. There’s something so romantic about one stranger paying the way for another stranger. I’ve always loved paying for the car behind me when I go through tolls or covering the order of the person behind me when I visit drive-thrus. I think a lot of people enjoy the unique feeling of giving something to a stranger that you will never meet and who will never be able to thank you.

Butterflies need heat to be able to move. When you see them resting in the sunshine, they are warming up their wings so they can fly.

SOLRAD: How many of the 2000 books in this print run have already been paid for? Did you have concerns before unveiling the project that you might have trouble getting people to pay it forward?

Luke Kruger-Howard: I still need to do a deep dissection of the numbers, and I will release those publically when I do, but it’s looking like we’re going to be breaking even or possibly just a hair short. It has been a really encouraging first showing in that just about all of the 2,000 books have been spoken for and the cost of those books has been shared across about 400 or so kind strangers who have paid it forward. Judging by the way the numbers have dropped off after the first week, I’m not expecting we will be able to reach our second goal of raising additional money to send to RAICES, but I feel like with a few adjustments we will be able to get there with our next release.

SOLRAD: Is anyone involved in organizing the project apart from you? Did you go through a testing period for the project or a beta version of it?

Luke Kruger-Howard: As of right now Goes Books is a solo effort, but I have so many amazing friends who have let me pick their brains or word-vomit at them over the last year that it doesn’t feel entirely like I’m running the ship on my own. And the reception since we launched on April 15th has been so overwhelming – I’ve had a number of people reaching out with suggestions on how to improve things and even asking if they can somehow get involved. That feels encouraging.

SOLRAD: You go into a lot of detail regarding why you think capitalism is deleterious to the creation and pursuit of art. Could you articulate how this has personally played out for you during your career as an artist?

Luke Kruger-Howard: The most tangible example of this is probably sitting in my studio closet. Stacks and stacks of half-finished comics projects that have all been abandoned over the years because I’ve let extreme doubt about their viability in the marketplace kill them. It’s hard enough to bring a project across the finish line without thinking about how it will perform as a productor what kind of popularity it will garner. So those pages of finished comics and thumbnails that remain to be turned into finished pages sit there collecting dust. I know so many artists who could say the same thing. I can’t tell you how many of my favorite comics serials will never be completed for the same reasons I mentioned. That alone speaks volumes about what a capitalist framework can do to the creative spirit. Some people function incredibly well in that framework and that is great, but I can’t say that I’ve personally thrived when I try to engage with it – I know a lot of people who haven’t. I’ve let so many projects die on the vine that didn’t have to.

On a more emotional note, I can say I’ve spent so much of these last 10 years in a constant spin cycle of self-doubt, overworking, jealousy, competition, gear shifting, emotional fatigue, and on and on. Don’t get me wrong, there have always been amazing and beautiful things along the way, but my inability to escape that spin-cycle even while those beautiful and amazing things are happening has forced me to take a hard look at things. I’ve been so incredibly lucky to have worked with amazing publishers like AdHouse Books and Retrofit/Big Planet Comics. I’ve checked off some of those big life goals like selling gags to the New Yorker or being nominated for an Ignatz. Yet I often find that those moments of “success” have been followed by periods of deep depression. Why is that? I think it has a lot to do with how I expect those accomplishments to make me feel compared to how I actually end up feeling. Those accomplishments don’t get you any closer to a sense of happiness or completeness, even though the system seems to teach you that it somehow will. Something in this system is not functioning properly (or maybe that’s exactly how it’s meant to function).

Butterflies can see colors humans cannot.

SOLRAD: How much has graduating from art school and later working for the same school (CCS) influenced your worldview? Have you felt pressure to achieve financial success as a result of the experience, beyond simply owing a lot of money in loans?

Luke Kruger-Howard: I would imagine that nearly all of us feel pressure to achieve financial success no matter what our background is, but I would say that the CCS environment can really equip you with the skill set to hold your own in a competitive comics marketplace. There’s a reason why you see such a large number of CCS alumni digging their heels into a million different corners of the comics community and refusing to go away. CCS is very strong at instilling a steadfast spirit in cartoonists and it also forces us to learn how to navigate a competitive environment. I don’t mean that in any sort of negative way either. I feel very positive about my time at CCS and I believe in what it manages to inspire in so many of its students. Still, there’s no doubt that a natural personal goal for me after graduating was to find a way to gain legitimacy and financial viability in the comics community. Because CCS does such a good job of teaching students about what options are out there for cartoonists, it is very easy to latch on to a specific success ladder and start climbing.

But I will also say that this whole conversation we’re having right now, and this Goes Books idea, are also born out of the CCS culture. Because a whole other aspect to the CCS community is long-lasting friendships and the sea of fellow cartoonists who are always building you up when you’re down and will always take your call when you’re trying to work through something related to your comics practice (or your personal life). That strong sense of community and belonging is everything when it comes to what I’m doing now – you learn to really identify and value the emotional revenue you get from your classmates (and as a teacher, from your students and fellow faculty members). I know deep down that I can rely on that community to support my work no matter how niche or unmarketable it is.

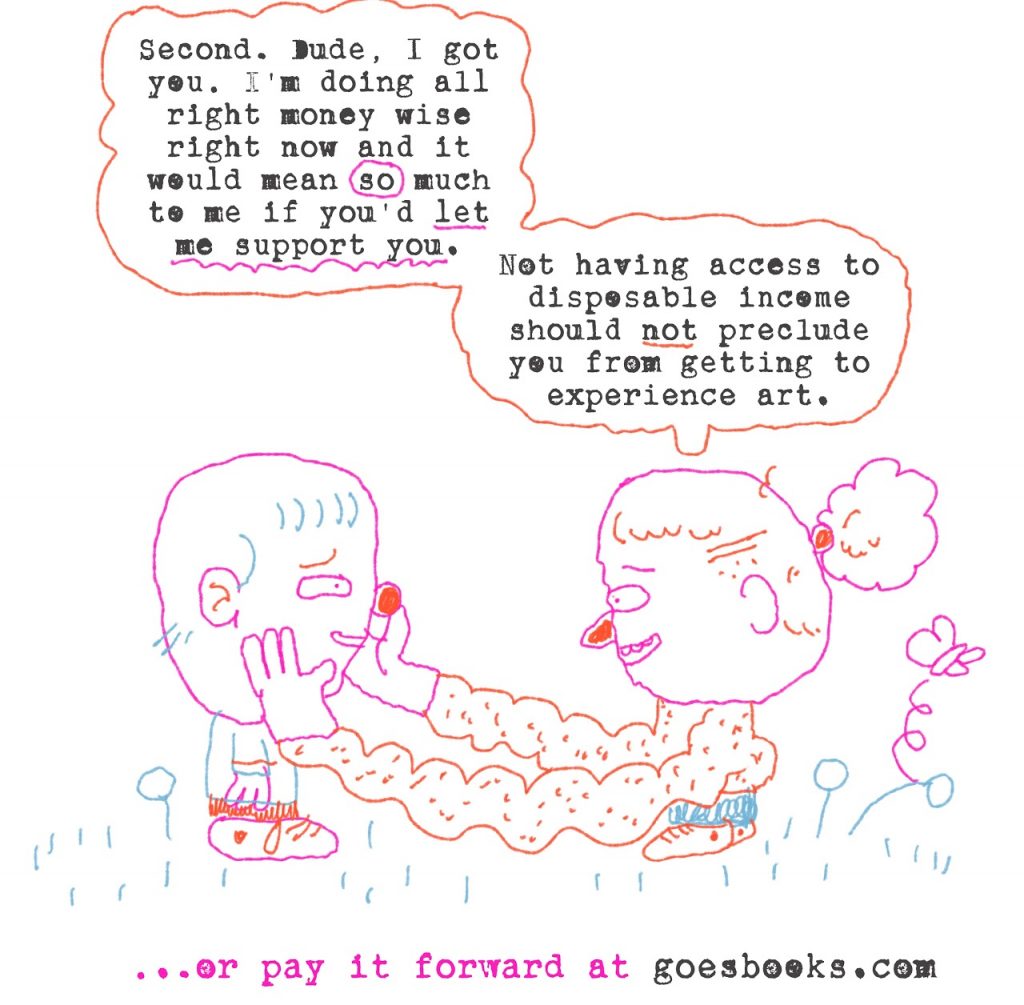

SOLRAD: It’s telling that you spend a lot of time on your site assuring people that it’s OK to ask for a book for free for this project. Do you find that capitalism’s grip on our collective consciousness is so tight that guilt has been a common initial reaction to Goes?

Luke Kruger-Howard: Absolutely. I’ve had loads of people reaching out to me since we launched to tell me that they want to pay-it-forward but that money is just too tight right now. They feel too guilty to sign up for a free book, and that is the antithesis of what I want people to be feeling. What that tells me is that we have all been taught in one way or another that our value as people is inextricably linked to our ability to contribute to the marketplace. If you are in a position where you feel like you are “taking” more than you are “giving” then our system sees you as some sort of drain on that system, which in my opinion is the world upside down.

With Goes Books I’m hoping to encourage a culture of cooperation where everyone contributes what they can to see that the greater whole can partake in what it has to offer. That means in part that some people who can afford it might pick up the financial slack for others, but it also means that we have to change how we define what a contribution even is. In my mind, a person who accepts a free book and reads it and gets something out of it and turns around and engages in their world is contributing just as much as somebody else who throws $20 into the community pot. Goes Books needs both these things equally to exist and to be a thing worth keeping alive. I don’t want to build something that values those who contribute money over those who contribute in engagement, emotional revenue, readership, or any other form of contribution that we don’t typically care to define as such.

SOLRAD: You stated that one of your goals was to create a relationship between artist and audience that wasn’t mediated by money. What is your ideal relationship between artist and audience? How does capitalism disrupt that, beyond limiting a potential audience?

Luke Kruger-Howard: I’m done with the reductive concept that the creator is the person who is providing something and the reader is the person who is receiving something. I don’t care to think of that relationship as a transaction or to think of the stories that are nearest to my heart as a product. Does that mean I will never sell my comics again? No, of course not. But it does mean that I’m actively looking to be careful around systems that naturally encourage creators to fall into a transactional relationship with their readers. I don’t think most artists get into this crazy comics-making game because they want to make money – I don’t even think most publishers get into it for that reason. I would guess most of us wanted to make comics or publish them because we love the medium and we have stories inside of us that we want to share.

I’d like the relationship between reader and creator to be seen and experienced more as a mutually beneficial one (because it is). Remember Eleanor Davis’s amazing acceptance speech at the 2015 Ignatz Awards? She said, “we’re here ‘cuz we want to show one another who we are. We come with stacks of shitty, little, stapled, Xeroxed things that have our whole selves inside them. We give them out in defiance and in love… we say, ‘this is me’… and we say, “I hope you make more.”

Isn’t that amazing? I encourage everyone to watch that whole speech on YouTube. I think that’s exactly the relationship I want to nurture between artists and readers with Goes Books. I also think capitalism is particularly adept at eating away at that kind of relationship until you wake up one day and realize you’ve stopped prioritizing it altogether. There’s no doubt to me that a capitalist framework has an extremely limiting effect on how many readers a creator can reach, but that’s only a small portion of the damage it can do. It eats away at our ability to make the stories we want to make. It teaches us to feel like we’re failing if we’re not meeting the narrowest of criteria. It asks us to overwork ourselves and to see that as some sort of positive character trait. It encourages us to look over at our fellow creators and to measure ourselves against them (as if that’s remotely an accurate way to measure things). And most deleterious it forces the creator behind a register and the reader in front of it – which is to teach us as creators to hide the most sacred aspects of who we are behind a paywall. As if to change Eleanor’s speech to say instead, “we’re here because we want to show each other who we are, but only the people who are willing and able to pay for it.” If that were really how we felt, things like webcomics would have never exploded the way they did and we wouldn’t be seeing the amazing abundance of content on Instagram day in and day out. Clearly, there is a big part of the equation that has nothing to do with what makes financial sense. Most business and publishing ventures around comics are not incredibly successful financially. Outside of the YR and YA heavy-hitters like Scholastic, most comics publishing companies have razor-thin margins and many small presses are operating at a near loss. But we still choose to do it, which tells me that there is motivation there that transcends the financial transaction.

I know that we live in a capitalist society and I’m not naive enough to believe that Goes Books can somehow function entirely outside of that framework. We still have to eat and be clothed and not die. And I don’t believe artists who sell their comics are somehow letting themselves be swallowed up by an entirely negative system. Neither do I believe an artist should ever allow a company to ask them to work on spec or for free or for unfair wages. But I do believe that our system of money and the marketplace is inherently broken and we’re reaching a critical point in human history where we need to come up with a completely different way of framing how it all works or we’re not going to survive. There’s too much demand on a system that has way too much scarcity.

Butterflies were named for the fact that their poop looks like butter. Blame the Dutch.

SOLRAD: I’ve read that some artists have found that by making something free, it makes the audience feel like it has less worth than something you’re charging for. How have you combatted that obstruction to Goes?

Luke Kruger-Howard: There’s some truth to this experience for sure; I know I have had it. Part of it I suspect has to do with what we typically offer for free especially when it is printed matter. Those things tend to be short comics and we tend to give them away almost like we would a free promotional item or a goodie, and they’re usually sitting on a table next to our other comics that are typically longer, larger, and possibly more important to us. That’s all to say that I think we’ve already done a lot to subconsciously communicate to the reader that we might not see this free thing as possessing the same level of value as our other comics. I do believe in general we learn to devalue something if it doesn’t function in the marketplace. It must not be that good if they’re giving it away for free, right? To me that says more about how unimaginative a capitalist framework really is at evaluating art than it does about whether or not money has some sort of magic ability to make a story better – of course it doesn’t. If we woke up tomorrow in a world where everyone could have a free copy of My Favorite Thing is Monsters, that would have absolutely no impact on the quality of Emil Ferris’s story.

To combat this with Goes Books I’ve tried not to let myself present this in any way as lesser or less considered than any of my other books. GOES is a fully-realized book that is no different than a comic I might publish with Retrofit or AdHouse. I think that goes a long way toward assuring people that this book isn’t some kind of throwaway. I think the communal aspect of the pay-it-forward model helps people feel invested in the process and develop a personal desire to see it ripple outward, which in turn helps the comic itself stand out as something substantial. At least I hope…

SOLRAD: Could you expand a bit on the concept of emotional revenue? In particular, I’m fascinated by the possibility of it being a binding force for the community, as opposed to the way capitalism foments competitiveness.

Luke Kruger-Howard: We all experience emotional revenue of some kind whether we are selling our comics, sharing them with the people around us, or posting them online. Emotional revenue is the dividends we receive every time somebody picks up something we created and gets something out of it and we feel that little tug in our chest that says something like, “I was here and I mattered.” Emotional revenue is getting that message in your DMs from a reader who just finished your latest comic and had to express how much it resonated with their own personal experience. Emotional revenue is the benefits you get from being vulnerable, from putting pen to paper, from that amazing smell that new mini-comics have when they come hot off the copier tray, and from feeling like you’re part of and participating in a community that cares about you and what only you can contribute.

Emotional revenue is a kind of revenue stream that is always running in the background, but the din and bustle of the dollars-and-cents marketplace has a way of drowning out our ability to stay in tune with it.

I don’t think Goes Books is some magic solution to being able to hook up to an emotional revenue stream, but making that revenue, rather than cash revenue, the focus of this project has legitimately allowed for a measurable difference. The most obvious being that normally at this point in a book release I would be coming down off that initial high of having a new thing in the world and people saying kind things about it and all that. That’s when I would start side-eyeing the sales numbers and thinking about possible award submissions and generally falling into a self-doubt tailspin of some kind. Why isn’t this book selling better? Why didn’t it make any year-end lists? Should I have chosen a different project? Why aren’t bigger publishers knocking down my door?

I’m not really feeling any of that with this project. I already know that by design this will be a failure in the financial marketplace. So I’m spending all my energy tuning into this other revenue stream. I’m reading the notes people are sending me. I’m letting myself stay engaged with the conversations it’s creating. I’m finding joy in slipping copies of GOES into free libraries in my area. I’m dreaming about what Goes Books could do next. And I’m also looking at other people’s work differently since the launch. I’m not feeling nearly as much of that same kind of competition and comparison. I’m just enjoying their work for what it is because it doesn’t have any relationship to my own work beyond the simple fact that it’s really great that people have the ability to put their stories out into the world.

I do think there is something here. It’s underexplored territory but I believe these sorts of shifts in our creative philosophy could help bind our community together in ways that I just don’t think the dollars-and-cents framework is all that good at.

SOLRAD: You were very careful on the Goes website not to condemn artists who try to work within the traditional publishing system and those who try to make a living as artists. How would you answer those who might say you are devaluing your own work by giving it away for free?

Luke Kruger-Howard: I think the essay on our website does a very good job of laying out why I think I’m not devaluing my own work and I would be honored if people end up being able to carve out some time to read it. But I also think this is a situation where I can already tell, even though it’s early still, that there have been huge benefits to this experience that I’ve never had with other projects. That tells me that there is great value here. It also convinces me of something I’ve suspected for a long time, which is that we are not particularly practiced at measuring value in all the endless ways that it can be measured. I can’t say yet because it’s still early, but I very well could be valuing my work more through the Goes Books model. Who knows, Rob Clough? Who even KNOWS?

One thing I do know is that butterflies glue their eggs to leaves.

SOLRAD: How did you settle on RAICES as your choice of charity to donate any profits made from Goes?

Luke Kruger-Howard: I’ve been raising money and donating money to RAICES since about 2016 as I really started to get tuned into the human rights crisis at America’s southern border. RAICES as an organization does a lot of good in trying to intervene in that arena and provide education and legal services to people who are essentially being treated as subhuman by our government. There is so much help that is needed in this area and if I can leverage a personal project to infuse even a tiny bit of money into that situation I’ll be happy. My experience with RAICES so far has been positive and I encourage everyone to read more about what they do.

SOLRAD: Given that you had no financial considerations whatsoever for Goes, did you find this was a freeing experience with regard to the kind of comics you included? How much have commercial considerations affected your work in the past, even personal work like Our Mother?

Luke Kruger-Howard: I’ve been lucky enough to work with small press publishers who are interested in publishing what you want to make and I love that about their approach. I’ve certainly struck out plenty of times when it comes to trying to pitch the projects I want to work on to larger publishers. I have gentle rejection letters stacked up all over my email history. So I have not had the experience of limiting my work for commercial consideration when it comes to the publishing experiences I’ve had with publishers, but I definitely can say commercial considerations have had a huge impact on what projects I’ve let be consumed by doubt and eventually shelved. The interesting thing about working on Goes in this new format is that my stress over the drawings themselves has changed. I would say that drawing has never been a particularly natural skill for me and that is an area where I always feel out of my league, especially when it comes to the ability to have commercial success. I’m not dealing with that with this project and I think it has to do with the fact that I have no motives for it to catch the eye of a publisher, earn a lot of money, or really do anything beyond hopefully be a story that people get something out of. Suddenly having the drawings come out however they come out is a much less horrifying prospect.

SOLRAD: What are your future plans for Goes? Do you plan this solely as a way to publish your own work, or have others been interested in this model as well?

Luke Kruger-Howard: I’ve been treating this first release as a kind of test run because I wouldn’t be comfortable running these sorts of tests on another creator and their work. If it turns out to be a beautiful disaster, the only thing I’ve really lost is my time and maybe some money. What I’m hoping to do is prove that Goes Books is a legitimate publishing model that I can use to prop up other creators along with releasing future issues of GOES. I’d like to use it as a platform to publish other artists that may not have all the resources I have here.

I also hope to see other people doing their own versions of this model, remixing it, and making it better. More than anything I wanted to start a conversation and I hope other people feel empowered by the idea that there are possibly endless unexplored ways to have success in the comics community. I know I do.

There are about 165,000 species of butterflies.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply