As a critic — particularly a critic of “underground” and/or “avant-garde” comics — sometimes you’re called upon to attempt to describe the utterly indescribable. Mind you, this is in no way anything other than an entirely good thing — at the very least it expands one’s vocabulary, sometimes even one’s consciousness — but it’s by no means always an easy thing. And there’s no greater challenge than attempting to convey, in terms anyone can understand, something of the unique spirit, character, and aesthetic sensibility of Mat Brinkman’s comics.

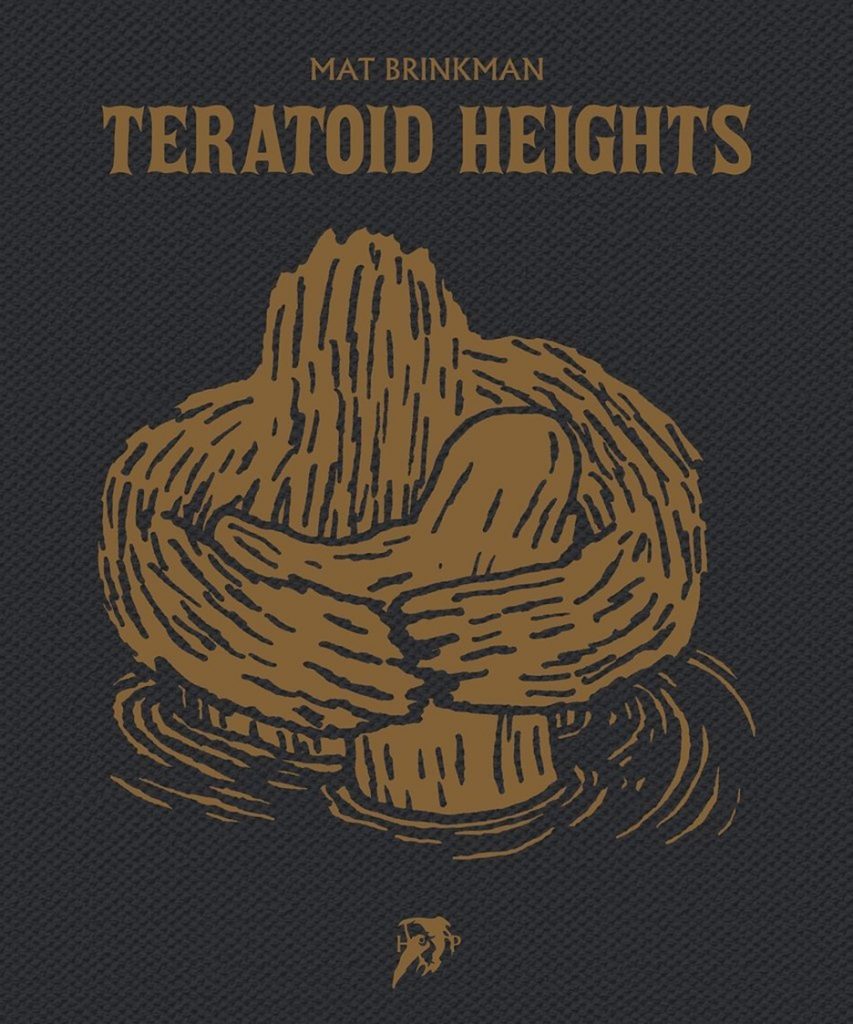

One of the co-founders of Providence’s legendary Fort Thunder cartooning collective/movement/”scene,” Brinkman himself is something of an enigma these days, having abandoned comics for music and maintaining no social media or even online presence whatsoever — but his work is just as tantalizingly mysterious, and always has been. Italian publisher Hollow Books re-issued — in handsome cloth-bound and foil-embossed “Museum Editions,” no less — two of his classic comic-strip collections, Teratoid Heights and Multiforce, in 2019, offering audiences new and old the ability to experience Brinkman’s justly-legendary creative output is fairly accessible (if expensive) packages for the first time in a long time. They’re getting a little tricky to find now, though it’s far from an impossible task. For the sake of brevity, though, I’m going to concentrate merely on the former book here, collecting material created and originally published between 1995 and 2001, but both are essential purchases if you can fit ’em in the budget.

Obviously, explaining why the work collected between these covers is so highly-regarded is my main charge here, but, fair warning: as hinted at mere moments ago, it may just be beyond my meager facility with words to be able to pull it off. I’ll give it the old “college try,” rest assured, but there are challenges — and then there are challenges in italics. Brinkman’s comics are the latter, and that’s one of the most exciting things about them.

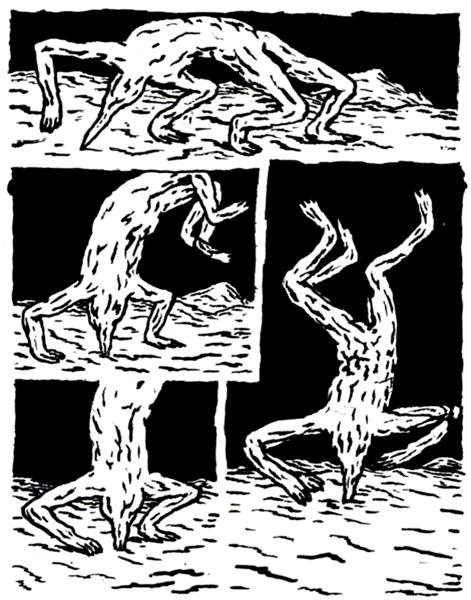

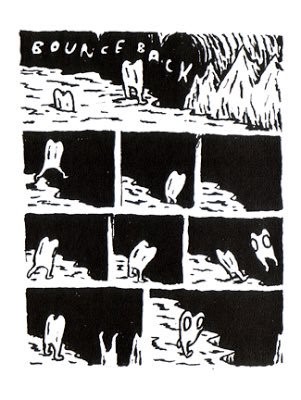

Fortunately, as a cartoonist rather than a writer, Brinkman himself certainly needs very few — if any — words to communicate his singular creative vision. And so he dispenses with them entirely, taking us on a guided tour through the caverns and hills and waterways and ever-shifting plateaus of his comprehensively imagined environment in a way that feels both casual and urgent, removed and immediate, based solely on the visual “evidence” offered to us.

This ethos carries over to the denizens of this world as well, Brinkman communicating their comings and going, toings and froings, using a viewpoint that is at once omniscient and deeply intimate, clinically removed, and almost painfully personal. If a glue-huffing teen were mystically imbued with the sense of holistic, visionary purpose that’s usually the province of only the most masterful of visual storytellers, the result might be something like this — but even then that might be a reach, as there’s quite simply nothing else “like this” at all.

And, yes, in case you were wondering, that’s basically the highest compliment I can think of. Which is perhaps my cue to think of some better ones. But I digress.

Thick, inky, borderline-oppressive black linework coagulates on these pages into forms and shapes that are intensely and inherently unfamiliar, yet in no way difficult to relate to. Brinkman has thought this world through, right down to the most recognizable patterns of individual behavior and social interaction, and to construct a fully-realized society like this out of such a delirious mish-mash of characters presumably conjured forth directly from the id without mediation is a staggering accomplishment in and of itself. However, to go one better by imbuing his creatures with an unbreakable through-line of warmth and humor is something else altogether. And “something else altogether” is as solid an “elevator pitch” summation of Teratoid Heights as I think you’re likely to find.

It’s easy to see how this work challenged an entire generation of cartoonists to “up their game”. Few things are so visually literate and hitherto-unseen simultaneously; few things are grasped so easily while remaining so ultimately and staggeringly confounding. Threading the needle between the known and the far less so with a deceptive and illusory (but no less “real” for that fact) ease, Brinkman accentuates the essential characteristics of each polarity in a manner that draws stark contrasts between the two. Yet he also very much would appear to be moving these disparate ends of the spectrum constantly toward a state of unification. At the end of each strip, for example, you know and feel precisely what’s happened — but you’ll be damned if you can explain it adequately to anybody else.

It’s well documented that the Fort Thunder artists fed off each other’s creative energy, but, as intimated in the title for this review, Walt Kelly is every bit the influence here that, say, C.F. and Brian Chippendale are. Brinkman takes some cues from C.F. and Chippendale’s experimental, fluid visuals, sure, but employs them in service of constructing the kind of “funny animal” (and, in this case, alien) pseudo-civilization of which Kelly, and latter-day spiritual successors such as Jon Lewis, would be proud. They’d also likely recognize this work as being a natural outgrowth of their own artistic lineage. Again, this is about as high as compliments get with me.

Even taking all that I just said into consideration, though, it can’t be stressed enough that Teratoid Heights constructs, and exists within, no real “category” apart from that of instantly-identifiable auteur comics. In a pinch, I’d call it a work of genius, but ingenious might actually be more accurate: these are simple stories, with simple premises, told in fascinating and entirely unexpected ways. How about that — I guess I was able to find the right words to describe them after all.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply