After many years since our first meeting in 2017, across several book readings, gallery openings, and workshops in Montreal, I hopped on a call with illustrator, writer, and designer Matt Forsythe to discuss a whole new set of work releasing throughout 2025. Renowned for his catalog of children’s storybooks – with the latest addition Aggie in the Ghost having arrived in August – he has also contributed illustrations to the reprint of Gianni Rodari’s coveted The Grammar of Fantasy, as well as returning as lead designer to Adventure Time after many years apart from the franchise.

JULIAN: Hello, Matt! How are you?

MATT: I’m good. How are you doing?

J: I’m fine, welcome to my studio space!

M: Nice! You’re in Montreal still?

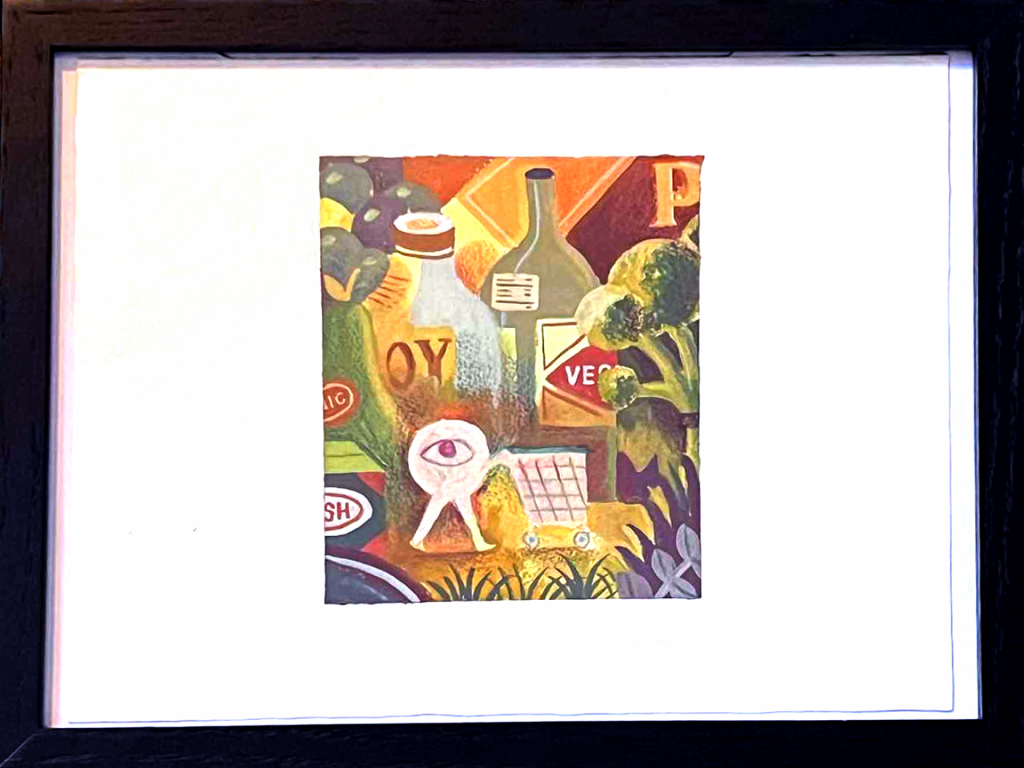

J: Yeah! I got one of your artworks up there – the guy pushing a grocery cart.

M: Oh yeah, I remember that –

J: You were doing a studio sale with Isabelle Arsenault at the time, I’m pretty sure. (…) You’re based out of Los Angeles at the moment, right?

M: Yeah – I lived in LA about 10 years ago [during the production of Adventure Time], left for Montreal after a few years, and I came back again 3 years ago, been based here ever since. (…) I work in animation, at Warner Bros. I have a lot of friends out here. It’s great, as artists, it’s…because everyone is doing what we’re doing, Julian. Drawing and going to conventions, making books (…) doing little gallery shows.

J: You’ve had a Gallery Nucleus show very recently!

M: Yeah, Nucleus, and then animation stuff…it’s just kind of nice to be around people who get what you’re doing. In Montreal, I felt like no one really understood what we’re doing, you know?

J: You found that to be the case?

M: Yeah, just creating your own path. A lot of people there have a very, like…9-to-5, 11-to-3 type of schedule, three days a week, and then they’re in the park.

J: I mean, on the flipside, the local culture representing a “don’t get too tied up in workflow” sentiment speaks to some larger issues we’re dealing with here, at least regarding the animation industry.

M: Give me a one-minute synopsis. What’s the vibe on the animation scene over there right now?

J: Currently, it’s Lay-Off Central here, buddy!

M: That was happening two years ago in LA, and I was like, “guys, it’s gonna be bad in Montreal”.

J: A lot of work…there’s some local work here if you’re in those indie circles, but it’s naturally all through grants, selling ideas internationally. But as I understand things, loads of the bigger stuff comes out of LA, out of Warner Bros, for instance, especially with a local studio like Tonic DNA (formerly Pascal-Blais) – they worked on a lot of Looney Tunes – and so if LA isn’t doing well, that can really trickle down to business over here.

M: A lot of the crew I work with now were sort of art directors on that [Looney Tunes]. Nick Cross, who also did Over the Garden Wall.

J: He’s pitch perfect for that retro aesthetic.

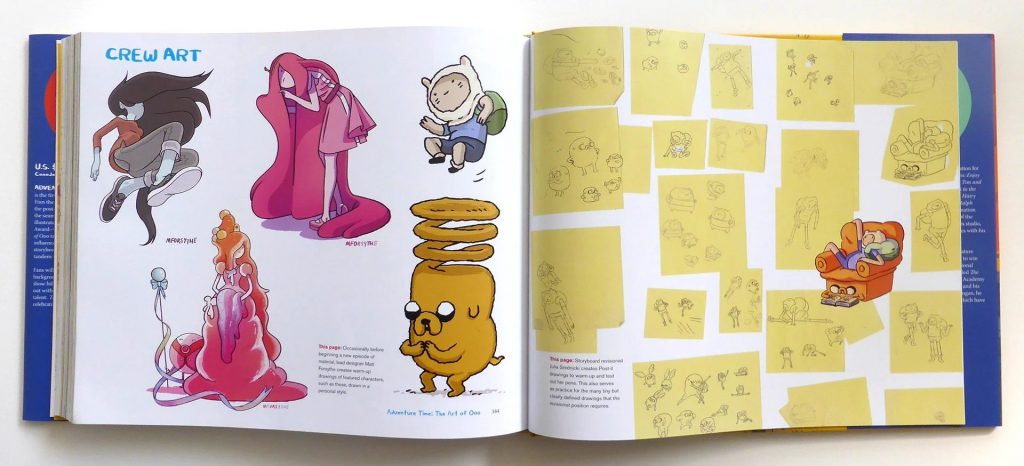

M: Yeah. And he’s working on Adventure Time right now. (…) There’s two spin-offs – Fionna and Cake, and Adventure Time Side Quests. A bunch of [older staff] have come back for that.

J: You’d mentioned in the past, your background wasn’t directly tied in with the art world, necessarily. No schooling or anything of the sort. So when you got that opportunity to work on Adventure Time, it was something of a surprise that there’d not been more hazing or anxiety around qualification – it was all “go-go-go” from the outset. I was curious, as you’ve returned to the series for the first time in a decade … How has the working atmosphere changed, and how has it remained the same?

M: Now it’s more laid back. There’s just less shows, there’s less people, less intensity. I mean, Adventure Time is not trying to prove itself. It’s already a global thing, it’s not trying to define itself. 10 years ago, there was a lot more stress, everyone was sleeping under their desks.

J: And there’s been rumblings, too, about a movie being made. Practically over the last decade, there’ve been utterances here and there…

M: To be honest – I’ll be honest – I don’t really care.

J: [Laughing] No!!

M: I left the show when I felt like it was starting to lose interest to me personally. When it started getting boring, I left. And this has been a fun year, just because I really wanted to work with these people again. Like, I love … It’s run by Nate Cash, who’s an old friend of mine. You know, Jesse Moynihan’s on it, Tom Herpich – these are my idols, and also my friends.

So I worked on my books for a decade, I worked on an animation project here and there, but it was so exciting just to work on the team.

J: That was the draw, for you?

M: Really, who knows what they’re going to do with the show. I find the creative process gets so diluted if there’s not a lot of guidance.

J: Yeah, it’s a very drawn out process, and, moreover, there can sometimes be a lot of cooks in the kitchen.

M: Well, what are you doing right now? Are you doing some animation stuff for studios in Montreal? Are you doing your own thing?

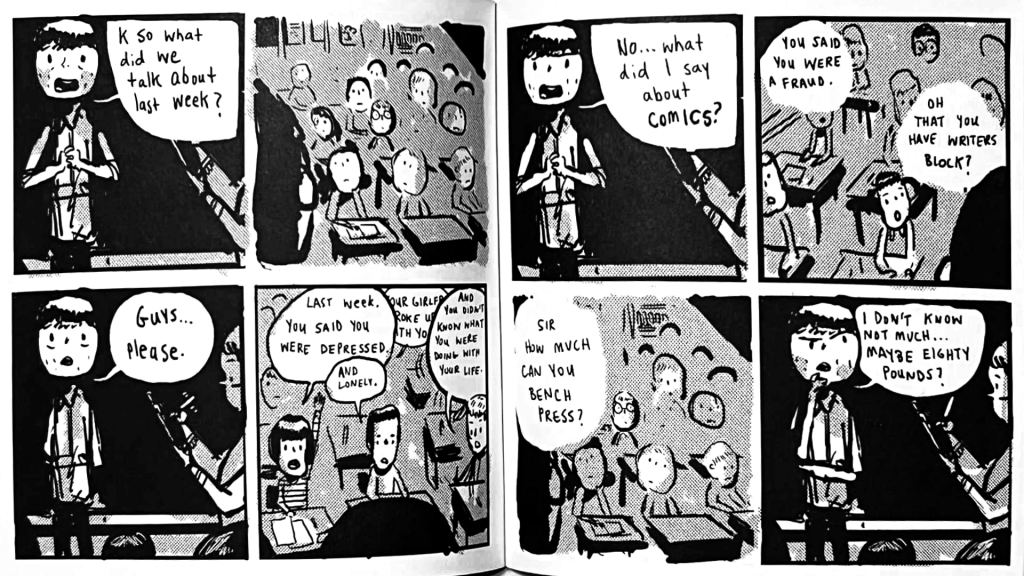

J: Currently working away at a couple of animation projects and commissions, some grant applications. (…) I wanted to mention to you that I was teaching stop-motion animation to grade-schoolers for a little bit – and I’d read your little comic, Comics Class, sometime before that job started up…and it felt kind of prophetic.

M: [Laughing] Yeah?

J: No, yeah, it was delightful.

M: There’s something ludicrous about teaching kids that aren’t there by choice.

J: I mean, they really liked 2D animation, on FlipaClip, so I started teaching that instead. I did get a lot of hugs by the end of the year, so that was okay. But a lot of them were, unfortunately, obsessed with dicks and balls –

M: Careful, bro!

J: I know! I told the supervisor – I mean, apparently they’re like this all the time.

M: Dicks and balls don’t go well together with teaching. And I don’t usually accept hugs [laughing].

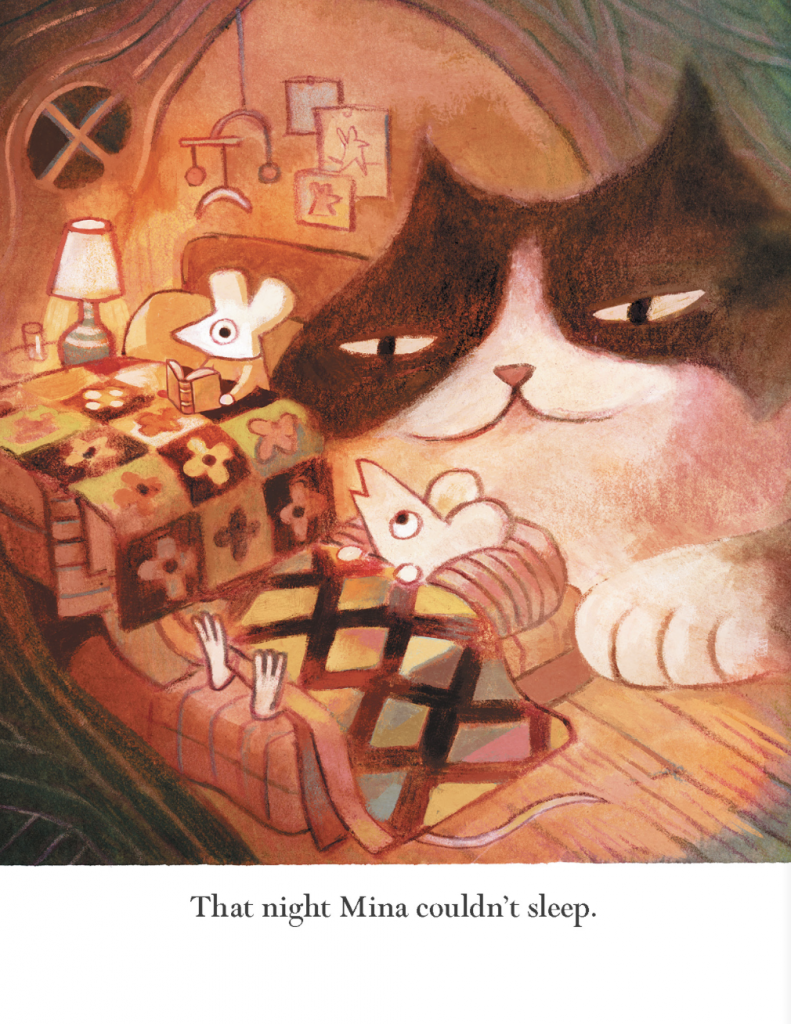

J: Comics Class was one of your earliest published works, and certainly something I’d related to, perhaps now more than ever. But I wanted to ask you about some of the books you’re coming out with right now. To start, there’s your storybook, Aggie and the Ghost…

M: I used to make comics for Drawn & Quarterly [or Koyama Press, like Comics Class], and I don’t really see a big difference between what I do now and those comics. I think there’s just a formal line that people like to draw in the sand. They like to say “oh, these are comics, and these are picture books”.

I mean, Ojingogo was a comic I made 20 years ago, and it’s like a picture book. It just happens to be 120 pages.

J: It’s all sequential, you would say.

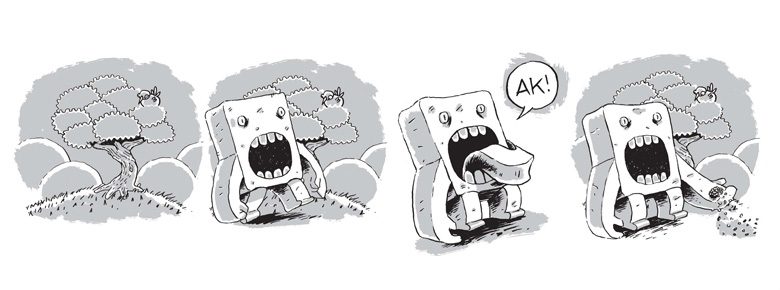

M: Yeah, they’re both sequential art. On some pages of this new book [Aggie], I have some comic panels, a couple pages where it’s [formatted] like a comic.

J: Again, effectively not all that dissimilar to what you’d done with Ojingogo way back when.

M: And it’s like, I don’t know…it’s hard to find comics that are really engaging these days. I know older people always say that about music and stuff, but it feels like everything has moved into this very market-based…you know, I was making comics, we would sell them for $5 –

J: Comics Class has $5 slapped right there on the cover.

M: Yeah, and that’s my instinct, I’d make a comic and sell it for five bucks. Now you go and people sell them for $40, for a riso zine. They all have like these YA book deals for $60,000, and they all seem like the same book! It seems like the same thing that’s getting commissioned by Scholastic over and over again.

J: I can think of a few names that come to mind, local folks who take on a more laissez-faire attitude to their output – James Collier and several others I know here in Montreal, for instance, are putting out free zines called Bottleneck – where they make the thing, and they move right on along.

M: Everything out of Pow-Pow is interesting to me.

J: Can you point to something of theirs, for the audience?

M: Yeah, I have one on my shelf, hold on – [holding a copy of Mirion Malle’s Beware Her Fury]

J: Mirion Malle?

M: Yeah yeah, I love it, for me – I know she’s back in France now – but I get that vibe of the Plateau, Montreal. I like the way they make comics (…). These are, you know, slice of life. They’re really raw and voyeuristic. Julie Doucet, I like, and anything Pascal Girard does is interesting to me. (…) Deep diaristic stuff. Even the Kate Beaton book [Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands] that went huge two years ago is just…diary comics, you know?

J: In your own writing, you tend to bring in your lived experiences, albeit in a heightened fantastical manner.

M: They’re absolutely, super autobiographical. I’ve made three books now, and they’re all directly lifted from my personal experiences.

J: Where does that shine through in Aggie?

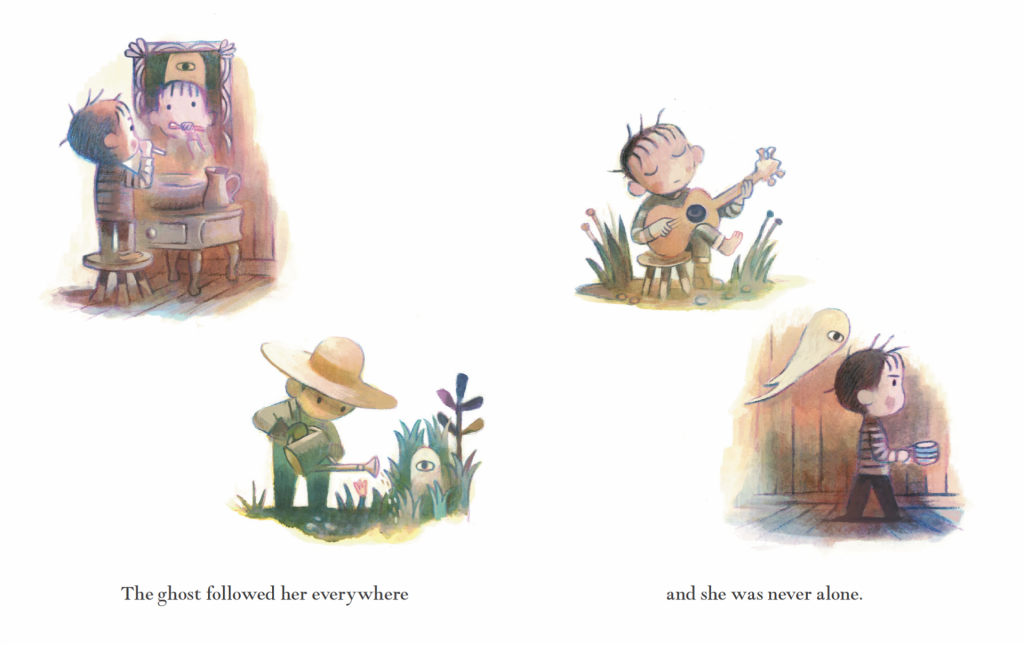

M: It’s like, the Ghost was this sort of idea of this regret following you around. This mistake you’ve made. You can’t shake it, you have to live with it – and if you go into psychotherapy, there’s ways to look at that. Call it ‘shadow work’. There’s a great book called Owning Your Own Shadow, but it’s all like Jungian concepts – how do we live with our shadows? Some people ignore it, some try to engage it.

J: Mm-hm.

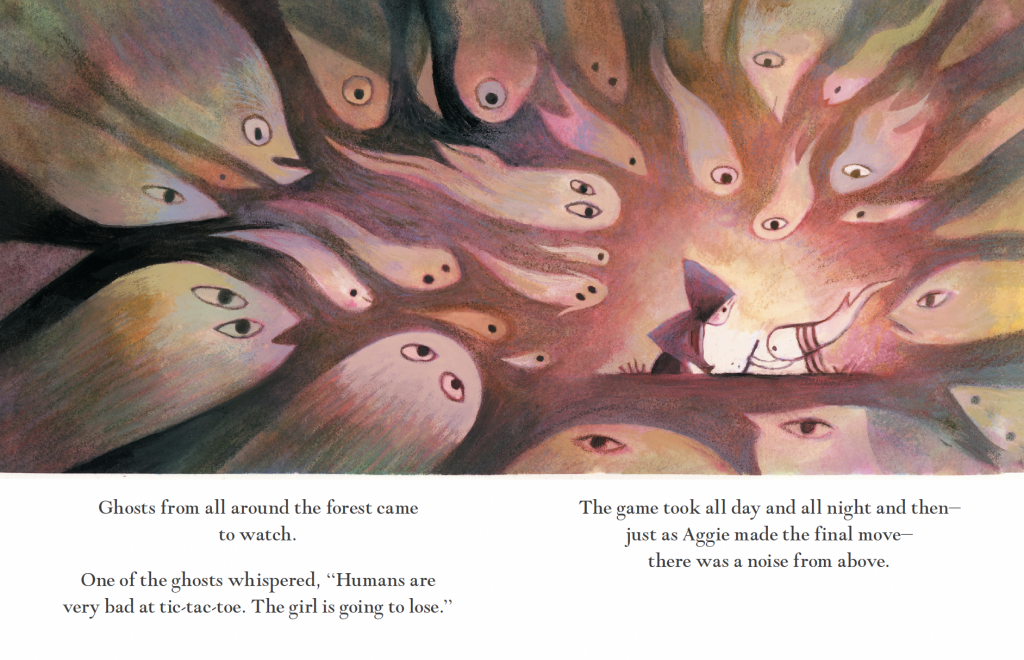

M: There’s that scene in The Seventh Seal, where the Knight plays chess with Death. That’s like engaging with your shadow, and I thought, “wouldn’t that be fun if that was a picture book?”

J: Like how the characters in Aggie play tic-tac-toe!

M: Yeah – that’s her facing her shadow. And in my own case, facing my regrets, my mistakes. In that sense, it’s deeply personal. (…) The way these books happen, they all wrap up a bunch of personal themes.

J: It’s excellent, too – it brings out some concepts that you would see explored in the book you’d recently illustrated for, Gianni Rodari’s Grammar of Fantasy. The tic-tac-toe game reflects the idea laid out on page 107 – wherein, through a standard narrative, oftentimes you introduced an additional element, such as the Little Red Riding Hood in a Helicopter example Rodari provides. As a means of engaging children with a playful sense of spontaneity, I found your book Aggie especially exceptional,

M: I hadn’t thought of that!

J: Moreover, I’m curious – I don’t know to what extent you’d previously acquainted yourself with Grammar of Fantasy, or aimed to align with the concepts of that book – where did your passions lie in regards to taking part in this newly minted edition? It wasn’t just another illustration gig for you?

M: It’s definitely not just an illustration gig – if it was, it was the worst paying gig in history [laughs]. Well, it took five years and there’s over 60 paintings! I don’t how you would even charge for something like that, but (…) the book is about two deeply philosophical essays, about the role of art and childhood and creativity, playing games, democracy…and then it has about 20 games, or prompts, in between those essays.

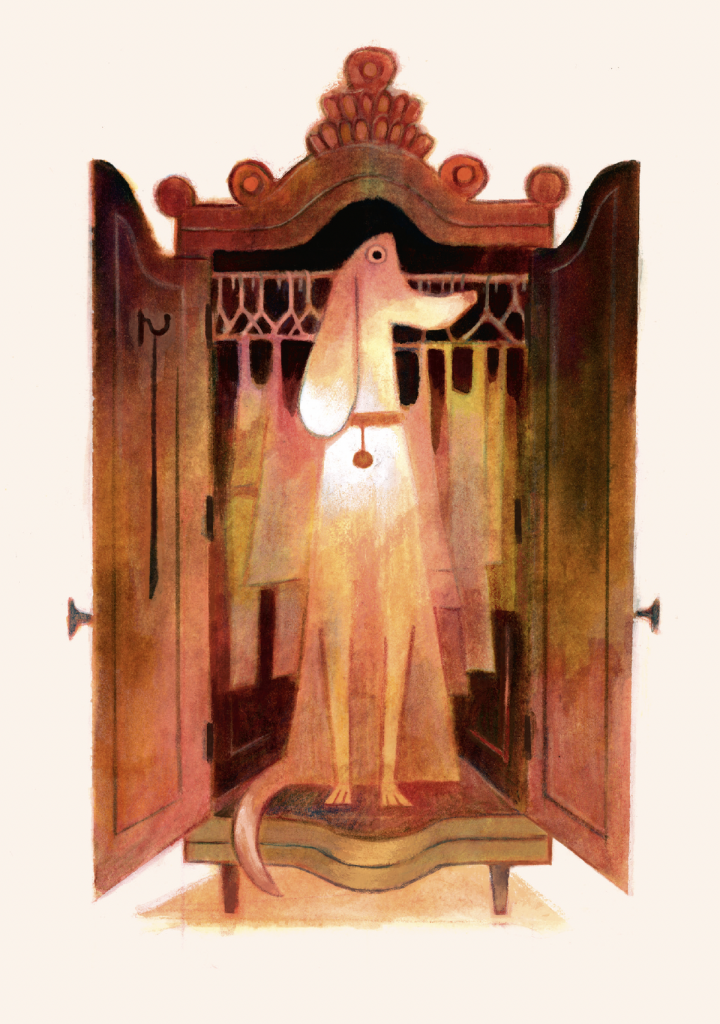

I don’t necessarily identify with all of them, they’re not all relevant to my process. But he talks about distance between ideas – one of the book’s main concepts – the fantastic binomial. It’s like creating distance between ideas, like helicopters and Red Riding Hood, and wolves, and what energy comes from these things. That’s central to everything I do.

Distance between ideas, distance between image and text, between text and text, page and next page, layer of colour and another colour. These are all things I’m thinking about constantly. (…) He uses the example of ‘dog and wardrobe’, but in my books, it’s ‘frog and drum’, ‘girl and her shadow’. So when I work on these projects, I think all about these polarities.

J: I was going to ask, too, how selective were you with the choice of illustrations themselves, in representing the literal text, versus creating a polarity between the text and image? There were some paintings you could easily attribute to the writing of a given chapter, but other times it was like you were creating a whole other energy alongside the text.

M: Yeah! It was a five-year journey. Claudia [Bedrick, editor for Enchanted Lion Books] and I had gone in different directions, where we’re like, “I’ll try and take one idea or one word from this chapter and follow that into a little dream image”. But other times, I was like, “you know what, I have this other painting, and I have 10 years of paintings that I could pull from (…), why don’t we put that image beside that image”? (…) And so, it did create this sometimes false distance, which made an interesting connection for the viewer.

I think, for a lot of people when they’re reading it, they’re like, “what the fuck is that?”, and I love that! “This doesn’t make any sense! What does that cat have to do with the word ‘hi’?” Gianni Rodari would be like, “work it out!” We live in this society where everything is fucking spoonfed to us. Everything’s Marvel Universe! But Rodari’s whole thesis is (…), the audience is a participant in this democracy. They’re a participant in the creative act. And I personally love that, too. That’s why I love old films and foreign films, because there’s more between the concepts, and they allow the audience to bring more to the film.

J: Less commercialization, less standardization! So often you can anticipate a narrative play-by-play, beat-for-beat, and I love the way Rodari’s book challenges an audience to engage in storytelling as a participatory act. Tying that into the spontaneity of children was a great conduit for these notions.

M: I do workshops and readings with kids. And I’ll say, the kids are no challenge to work with. Kids are in touch with their creativity. There’s an intuition to the artistic life that kids have innately. The challenge is adults, the intermediating adults – the parents in the room, the teachers in the room (…).I think they see the world, it’s full of fear and danger, and they react that way with kids, where they go, “let’s just give them something safe in their childhood”, instead of allowing the kids to solve problems, like Rodari wants them to – like kids want to.

I honestly do think that we’re all just big children, and children are just little adults. They’re dealing with a lot more emotions on a daily basis than we are. We’re much more numb to the things that they’re feeling. So the challenge really is about getting past the gatekeeping adults, to create more interesting art for children. Right now, we have a homogenous, monotony of art, in terms of picture books, and even comics. I mean, most comic artists 20 years ago, that would have been making zines, are now making YA books for kids. And they’re really monotonous. They’re all kind of the same summer camp story – “I wouldn’t fit in, and then I fit in” – like okay, great, thanks.

J: Something I love about your writing, across comics and storybooks – and especially something Aggie does so well – is how you cut through any pretense or preamble, and place direct attention towards the emotional honesty of your narratives. Oftentimes, simplicity is anticipated from this art form, but what you bring is a sense of humorously direct universality without softening your narratives.

M: I mean, the way I think about the children with respect to my books, is that they’re one audience. I want to be inclusive of them. I want them to love the book, obviously. I’m an audience, too. I’m the main audience. But I want the kids to love it, too, and I want them to love it when they are parents later. I want them to pick it up when they’re teenagers and still be like, “you know what, this kids’ book was fucking cool. This was a weird book that I loved when I was a kid”. (…) Maybe when they’re adults, they’ll be like, “oh this was actually about Jungian psychology”.

So yeah, I’m thinking of it like 4D chess, because those are the sort of books that have always meant a lot to me.

J: I wanted to ask about how – I guess you’ve already touched on this a little – how you develop your solo projects…could you describe in a bit more detail how that works in the context of collaborating with an editor, or a publisher? How do you intuit who to involve in that gestational bubble wherein a concept is growing?

M: It’s difficult – because you know, and I think you probably feel the same way, but all art that I love comes directly from someone. It comes directly from their own emotional experience, and it’s very direct…it’s not watered down by 19 emotional experiences, it’s a very personal thing.

So when you make a book with an editor, you want someone who’s not trying to include their emotional take. You want someone who is there to help protect yours. I worked with Paula Wiseman for the last three books, and she’s very like, “you need to do what you need to do, and you need to make what you need to make”. And I think, some things work, some things don’t work, but they’re honest, you know? When I look at some of [my] drawings, it feels a bit cringey, but so what? It’s real.

Honestly, when we look at artists we love, they all make crap sometimes. The crap adds texture to their experience.

J: Yeah, it forms their canon, shapes out their catalogue.

M: Exactly, for sure. So I’m not looking for someone who’s like, “oh can you make this edgeless and make this more commercially successful?” I’m looking for someone who’s going to want to keep the edges, help keep it a little raw. Anyway, Paula is amazing. I’m really worried about who I would work with if I don’t work with her, because not many people get it, especially if we’re talking about living in this world full of fear. The book industry is not thriving, so editors are not coming from a place of boldness right now.

J: Sales are down? People aren’t willing to take some riskier bets?

M: Yeah, the same as every industry, the economy – we’re basically in a recession. Everyone’s losing their jobs. Layoffs in animation, layoffs in tech.

J: Layoffs across the board!

M: And people are feeling it. I’m happy to say, I think, my books are doing okay.

J: In the past, you’ve collaborated with other writers – Lemony Snicket, for instance. Do you feel, at this time, more pressured to jump into a duo effort as an illustrator? Or can you still find the capacity to be selective with your projects?

M: Well, I’m not starting out or anything, so I’m okay. There’s really no interest anymore in working with writers. I’m a writer, I’ll write my own work. (…) I’m not saying it won’t happen, of course, but I’m even more selective now. The text needs to be overwhelmingly powerful to take on that other person’s work, given how long it takes to illustrate a book. (…) I’ve worked my ass off the last couple years, I’ve worked nonstop this year, on three books, and I made a TV show.

So I’m in a position where I can take a step back and breathe, and I don’t have to take everything that’s thrown my way.

J: Returning to that notion, that art had been considered something of a frivolous pursuit in your upbringing. Your family had come from more of a working-class background, right? Does that have any impact on your artistic practice, the way you envision your career trajectory?

M: I’m from a factory town in Ontario, and none of my friends went to university. I’m still in a group chat with five guys, and they all work in factories or as tradespeople. They’re my best friends. Where I came from, I didn’t know you could be an artist, I didn’t have a lot of friends who were going to like SVA in New York or anything. I certainly couldn’t afford that $300,000 tuition, you know? A lot of artists I adore and admire, they didn’t go through that kind of standardized education, they just spoke to a real experience, they didn’t need filtering.

I’m not independently wealthy, you can always tell when someone is. They make really outside art that doesn’t have to find a place in the market. You’re like, good for you, I’m very happy for you, that you get to make these beautiful objets d’arts that don’t exist in the marketplace. Their parents have subsidized those works of art. But for me, I need to make work that exists in the marketplace, because I don’t have family money. Of course, I care if it resonates with people, but it also has to come from a personal place.

J: You figure a lot of comics artists are coming out of privileged backgrounds?

M: Well, it’s very difficult to get by on $5,000 advances.

J: Sometimes people will work out from passion, as with your work on Grammar of Fantasy. I’ve had some jobs that really didn’t cover all the bases financially, which of course isn’t always the realistic approach to living as an artist. But people do put out work in spite of low-income, drawing while they’re taking the bus –

M: Let’s be real, no one’s making a book for Fantagraphics while they’re on the bus.

J: I mean, it’s a step towards bigger things – but ultimately, yeah, we can’t romanticize too much, either.

M: I can tell you, a lot of artists – because I live in LA – in animation (…) went to Cal Arts and SVA, and that self-selects a lot of comfortable backgrounds.

J: Of course… and a major reality for many working artists is that selective and circumstantial upbringing is often the primary supplement to an art practice, supplying the means to expand their visibility and thus their opportunities where others may struggle to sustain that lifestyle. We’re seeing that gap widen further and further as the middle-class lifestyle grows increasingly unattainable for younger people.

Unfortunately, on account of scheduling, the conversation soon came to a close. We quickly discussed a few of Matt’s forthcoming projects – a good night book with Matthew Burgess, utterances of a new comic book he’s not altogether ready to comment upon – before we traded our farewells.

However, in recurring contemplation towards this subject, I returned to his book Pokko and the Drum, and its logline – “a story about art. And persistence. And a family of frogs that lives in a mushroom” – a strongly autobiographical angle, personal expression transcending a meagre means of living. A community forms around Pokko as she loudly beats her drum. Would, perhaps, regardless of income, this be an ideal means of expression and artistic output, to expand your self within a genuine, worldly communal experience?

Several weeks soon passed, and on a cozy Fall evening in Montreal’s Mile End, Matt joined a panel at Libraire Drawn & Quarterly alongside the likes of aforementioned publisher Claudia Bedrick, author J.F. Martel, and moderator Sruti Islam. When I arrived, Matt lit up and greeted me at the door, shaking my hand – “there he is, in the flesh!” – as he asked how I’d been doing. I, in kind, inquired into how his return to Montreal had been treating him.

“Oh, it’s a utopia”.

And certainly, not unlike his froggy counterpart, he was soon surrounded by friends and admirers, acquaintances new and old, to all of whom he shared the same beaming enthusiasm and earnest curiosity.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply