The woman’s body has long been a subject of objective fascination in art, but the ways in which it must present in order to maintain this fascination is startlingly slim. To be a subject of objectification, the woman’s body must remain stagnant, frozen in time – frozen in a death mask of beauty, of youth, and of false permanence. This presentation of the female body in art is inherently dishonest, as well as being largely uninteresting. What fascinates me most is the woman’s body as a grounds for transformation, as a place of not only beauty and youth, but also of extreme ugliness and decay. In that vein, I am fascinated by the woman’s body as a location of horror through transformation – the great potential that this body has to shock, disgust, and ultimately liberate. Hélène Cixous writes in her essay “The School of Roots,” from Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing:

In The Passion According to G.H., G.H., a woman reduced to her initials, encounters in complete solitude, face to face – even eye to eye – a cockroach, an abominable cockroach. In Brazilian the word for cockroach is barata, and it is feminine. So a woman meets a barata, and it becomes the focus for a type of fantastic, total, emotional, spiritual, and intellectual revolution, which, in short, is a crime. (112)

I have sometimes described myself as a cockroach, mostly in reference to the general resilience that I hope I have been able to embody, but also in reference to the trials I have experienced in direct relation to the physical body that I inhabit. There is freedom in this identification for me – a cockroach navigates the world in a straightforward and uncaring way, while still being considered an object of disgust by the majority of people. Liberation through the repulsive, liberation through the abject.

What, exactly, liberation is may be more difficult to define. In this context, I see liberation as a physical and mental act of breaking through what has been long established as our ‘rightful’ place as women, breaking into domains from which we have been rejected for millennia, domains which have been traditionally ruled by the male voice, the male body. I see this liberation as a place for women to reclaim the act of breaking down, of reestablishing a claim to disorientation and deterioration. This is a liberation that will also involve women returning to the repulsive, the things that shock and horrify, our inherent capacity to transform… perhaps into something society would deem monstrous.

Cixous opens her seminal essay “The Laugh of the Medusa” by urging, “Woman must write her self: must write about women and bring women to writing, from which they have been driven away as violently as from their own bodies” (Cixous 875). She also writes in her essay “The School of the Dead” that, “Writing, in its noblest function, is the attempt to unerase, to unearth, to find the primitive picture again, ours, the one that frightens us” (Cixous, Three Steps 9). As for the specificities that plague, drive, and differentiate the woman writer from the male, in her essay “Castration or Decapitation,” Cixous states:

Women who write have for the most part until now considered themselves to be writing not as women but as writers. Such women may declare that sexual difference means nothing, that there’s no attributable difference between masculine and feminine writing… what does it mean to ‘take no position’? When someone says ‘I’m not political’ we all know what that means! It’s just another way of saying: ‘My politics are someone else’s!’ And it’s exactly the case with writing! (“Castration” 51-52)

How, then, will the blatantly female texts differentiate from the male? From these lines of thought, I feel it is only logical that women’s writing return to reclaim the body that has long been repressed and sanitized through the art of men appropriating it. It is only natural that this reclaiming may be far from what we have been taught to recognize as the ‘correct’ presentation of the woman’s body in art. Also, that this reclaiming may venture into the world of genre – specifically horror. Cixous writes:

We’ve been turned away from our bodies, shamefully taught to ignore them, to strike them with that stupid sexual modesty; we’ve been made victims of the old fool’s game: each one will love the other sex. I’ll give you your body and you’ll give me mine. But who are the men who give women the body that women blindly yield to them? Why so few texts? Because so few women have yet won back their body. (“The Laugh” 885-886)

We are at an impasse in terms of women reclaiming their bodies through writing and have been for quite a while – the question of how this separation from the masculine and the modest will present itself artistically is ongoing. In my own writing, I find it difficult to feel as if I am making any progress at all, either internal or external. This I think speaks to the overwhelming loneliness that accompanies the journey of the women writer, though that loneliness is often imagined and a product of the isolationist society we have been raised in. Abjection as an artistic practice, though, is often inherently isolating and lonely, even when we as women writers have generations of women before us to look to.

Julia Kristeva’s Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, provides much in the way of relevant theory and comment on the subjects I have discussed above. The text explores the concept of abjection, which is defined by the Miriam-Webster dictionary as “a low or downcast state: degradation.” More specifically, within this context abjection is defined by The Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism (quoting Kristeva) as:

The abject is which ‘disturbs identity, system, and order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules.’ Filth, waste, pus, bodily fluids, the dead body itself are all abject, as are ‘the traitor, the liar, the law breaker with a good conscience, the rapist, the killer who claims he is a savior.’ (Childers and Hentzi 17)

After becoming aware of this definition, I found that I was constantly discovering pieces of media and art which I felt could be appropriately described as abject, and that these were often the pieces I was most drawn to. I also believe that this definition of the abject connects exactly with Cixous’ call for women to reclaim women’s writing – and by extension, their bodies – and the taboo expression that may transpire from this call.

Kristeva states, “There is nothing like abjection of self to show that all abjection is in fact recognition of the want on which any being, meaning, language, or desire is founded” (5). Kristeva expands on this insight in the following passage:

Abjection – at the crossroads of phobia, obsession, and perversion – shares in the same arrangement. The loathing that is implied in it does not take on the aspect of hysteric conversion; the latter is the symptom of an ego that, overtaxed by a ‘bad object,’ turns away from it, cleanses itself of it, and vomits it. In abjection, revolt is completely within being. Within the being of language. (45)

It is through this line of thought that I would argue abjection, and the full embrace of that which can be considered abject, is a necessary step on the path for women to reclaim women’s writing. The first section of Cixous’ essay “The School of the Dead” is entitled “We Need a Dead (wo)man to Begin,” (Three Steps); and though I know she was not referring specifically to the concept of abjection here – and though it may sound counterintuitive – I believe beginning with a dead (or almost dead) woman is indeed a fruitful start.

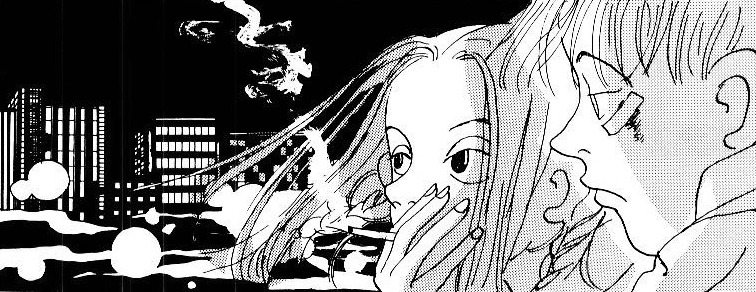

“A word before we start: Laughter and screams sound very much alike” (Okazaki). This is the line that prefaces Kyoko Okazaki’s masterwork of psychological horror and female abjection – the 1996 graphic novel Helter Skelter. These words work to somewhat prepare the reader for what is to follow: a disorienting and unsettling tale of the horror surrounding loss of control and the terror of inhabiting a female body. Before exploring the content of the graphic novel itself, it is relevant to acknowledge where Helter Skelter – and by extension, Okazaki herself – exist within the wider culture and categories of graphic novel and comics publishing in Japan. Okazaki is not only a female graphic novelist, she also consistently published works that fit within the josei genre, josei translating to “women’s comics.” Unlike its little sister genre shōjo (“young woman”), josei specifically targets the demographic of adult women. Okazaki’s exploration of genre and the grotesque are especially radical in this context, as they venture outside of what is typically seen as women’s interest and therefore marketed towards that demographic.

At the time of writing Helter Skelter, which would be her final work (Okazaki was hit by a drunk driver soon after it finished serialization), Okazaki was hardly a stranger to the subject of abjection. Her 1994 graphic novel River’s Edge follows a group of high school students each struggling with their own issues as they navigate the complicated landscape of coming of age. A focal point within the narrative is the existence of an anonymous corpse that two of the teens discover near the eponymous river’s edge, and which various characters return to throughout the story to examine and meditate upon. At one point in the story one character questions another:

“What did you think when you saw [the corpse] for the first time?” The character goes on to say what she herself thought, stating, “I thought, ‘take that.’…Everyone in this world pretends to be so pretty and nice; fuck them. Fuck you, stop this bullshit. I have no way out of this, but neither do you. So take that. That’s what I thought” (Okazaki 108-109). On the subject of the dead body, Kristeva notes, “And yet it is the human corpse that occasions the greatest concentration of abjection and fascination” (Kristeva 149). And Cixous opens “We Need a Dead (wo)man to Begin” by writing:

To begin (writing, living) we must have death. I like the dead, they are doorkeepers who while closing one side ‘give’ way to the other. We must have death, but young, present, ferocious, fresh death, the death of the day, today’s death. The one that comes right up to us so suddenly we don’t have time to avoid it, I mean to avoid feeling its breath touching us. Ha! (Three Steps 7)

This blatant examination of what society would probably deem at least unpleasant, and most likely, extremely taboo – the witnessing of a corpse without context – is also a textbook example of the abject, and something that Okazaki would weave throughout all of her works.

Helter Skelter positions us at the beginning of fictional supermodel/actress/it-girl Liliko Hirukoma’s downfall. At the height of her career, it seems from the outside that Liliko has everything – beauty, wealth, a handsome boyfriend – but unbeknownst to the public, her physical body is beginning to deteriorate from the inside out. Having undergone experimental full-body plastic surgery: “The only parts she’s kept are her bones, eyeballs, nails, hair, ears and twat… The rest is all fake” (Okazaki 33). Liliko’s body is now experiencing the side effects, and it isn’t pretty. Kristeva writes:

The body’s inside, in that case, shows up in order to compensate for the collapse of the border between inside and outside. It is as if the skin, a fragile container, no longer guaranteed the integrity of one’s ‘own and clean self’ but, scraped or transparent, invisible or taut, gave way before the dejection of its contents. (53)

This thought seems an apt description for the beginning deterioration of Liliko’s body, not only the “dejection of its contents” making themselves clear, but also the abjectness of Liliko’s being revealing itself in both the physical and mental sense.

What begins as a bruise on her forehead progresses into more bruises across her body, hair loss, physical illness, and a mental spiral into darkness that she will not emerge the same from. The physical manifestation of abjection within Liliko’s body mirrors the active abjection persisting in the world around her: Two cops investigate organ theft and suicides tied to the shady clinic where Liliko receives her procedures; Liliko’s assistant throws acid on the face of her ex-boyfriend’s fiancé at Liliko’s demand; Liliko’s overweight and plain younger sister begins her own journey of transformation upon witnessing Liliko’s. Kristeva writes, “Suffering speaks its name here – ‘madness’ – but does not linger with it, for the magic of surplus, scription, conveys the body, and even more so the sick body, to a beyond made up of sense and measure” (146). Lines are blurred – between the physical and the mental, between internal violence and external action – a perfect storm of chaos and abjection brews like fog creeping at the peripheries of these character’s lives. Though perhaps all writing (and perhaps by extension all psyches) is in some way at the mercy of the violence that permeates our world – to quote Cixous in “The School of the Dead”: “All great texts are prey to the question: who is killing me? Whom am I giving myself to kill?” (Three Steps 15).

Both the journey and outcome of Liliko’s descent is reflected beautifully through this quote from Kristeva: “A massive and sudden emergence of uncanniness, which, familiar as it might have been in an opaque and forgotten life, now harries me as radically separate, loathsome. Not me. Not that. But not nothing, either” (2). The male cop in Helter Skelter comments on this uncanniness early on in the narrative, stating: “The movements of her skin and muscles are out of sync with the bone underneath. Such a fascinating face. How can I put it? It looks perfect at first glance yet it’s off-balance. That’s what makes it so mysterious.” (Okazaki 32)

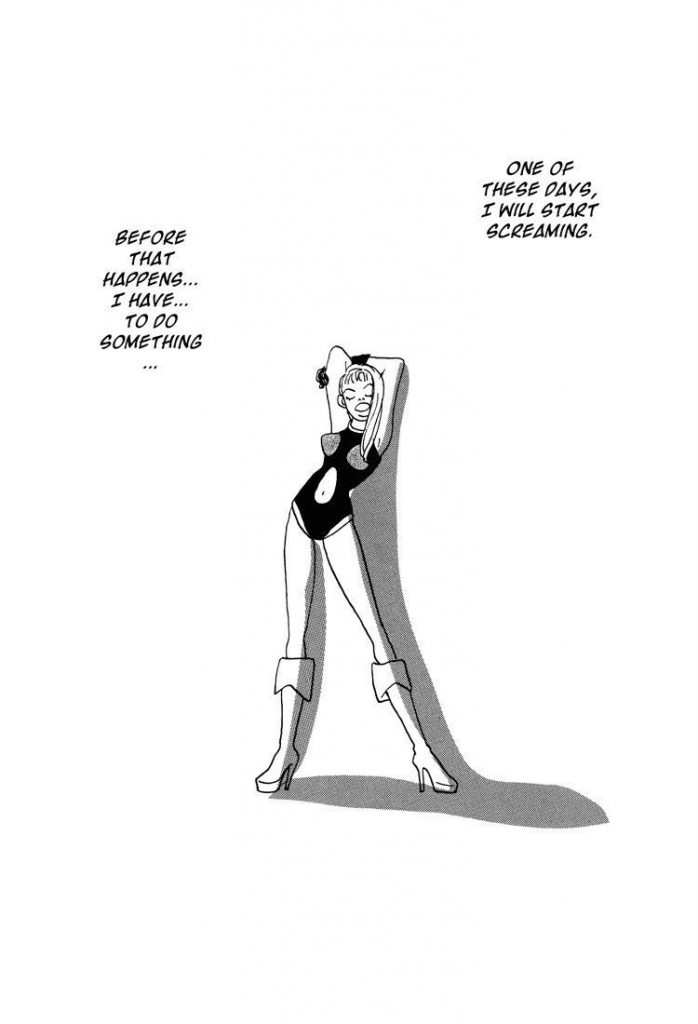

With this examination of the uncanny and separate, the question posed to the reader now is whether or not Liliko’s transformation into abject being means her doom, or perhaps, her liberation. In the late stages of bodily deterioration, Liliko arranges a final television appearance. The chapter opens with the headline, “The nearly forgotten Liliko made a dramatic comeback as a certain manner of freak” (Okazaki 284), seemingly recognizing that although Liliko’s physical body is still a public spectacle, choosing to present it herself in its abject (both physically and mentally) state works in a manner of reclamation. In preparation for her appearance Liliko “Envisions death. She simulates with all her heart the final show she would perform for everyone” (Okazaki 290). Here, Liliko reclaims the final act of abjection – death itself, and the becoming of a corpse.

Liliko, however, again defies the public’s expectations and doesn’t appear publicly at all, instead performing the final – and perhaps most female – transformation: the act of disappearing. In “The Laugh of the Medusa,” Cixous states:

It’s no accident…Women take after birds and robbers just as robbers take after women and birds. They go by, fly the coop, take pleasure in jumbling the order of space, in disorienting it, in changing around the furniture, dislocating things and values, breaking them all up, emptying structures, and turning propriety upside down. (887)

Liliko’s disappearance revels particularly in the abject, and is certainly disruptive, as the narration states that, “Liliko never showed up to the press conference. She vanished in a flash, like so much smoke. The only thing left in the blood-soaked hotel waiting room was a single eyeball that appeared to be Liliko’s” (Okazaki 306).

Kristeva references “a narrative between apocalypse and carnival” (141), which I believe quite aptly sums up Helter Skelter’s narrative arc and aesthetic presentation. It is an artistic gift to bear witness to a woman’s journey to and within the abject when that journey has been reclaimed and penned by a woman writer. There we can find a great depth of both the grotesque and the beautiful, an unearthed curiosity and a historical hunger – a great capacity to both discomfort and to heal. Near the end of Powers of Horror, Kristeva writes:

Throughout a night without images but buffeted by black sounds; amidst a throng of forsaken bodies beset with no longing but to last against all odds and for nothing; on a page where I plotted out the convolutions of those who, in transference, presented me with the gift of their void – I have spelled out abjection. Passing through the memories of a thousand years, a fiction without scientific objective but attentive to religious imagination, it is within literature that I finally saw it carrying, with its horror, its full power into effect. (Kristeva 207)

Here we may reflect on the true power of the abject through language, through the reclamation of putting words onto a page and the historical background that has previously driven women from such an action. We may reflect on the power of a woman’s words used to shock and disgust, to push an envelope that has been so expertly sealed by a society built upon patriarchy and silence.

In “The School of the Dead,” Cixous writes on reading: “It also saddens me… [that] very few books are axes, very few books hurt us, very few books break the frozen sea. Those books that do break the frozen sea and kill us are the books that give us joy” (Cixous, Three Steps 18).

Through my examination of Helter Skelter, I hope I have been able to convey the great importance and impact a book of this type can have on the reader both intellectually and personally, as it has had upon me. Cixous states, “Writing is learning to die. It’s learning not to be afraid, in other words to live at the extremity of life, which is what the dead, death, give us” (Three Steps 10). Studying Cixous and Kristeva’s groundbreaking and moving insights into abjection, the power of literature, and the existence of the woman writer, as well as reading a text such as Helter Skelter, I feel a personal responsibility as a woman and a writer to if not add to the canon of works such as these, then at the least to continue speaking on the necessity of their existence. I don’t want to be afraid anymore.

Works Cited

Childers, Joseph, and Gary Hentzi. The Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism. Columbia University Press, 1995.

Cixous, Hélène. “Castration or Decapitation?” Translated by Annette Kuhn, Signs, vol. 7, no. 1, 1981, pp. 41-55. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3173505. Accessed 1 April 2022.

—. “The Laugh of the Medusa.” Translated by Keith Cohen and Paula Cohen,

Signs, vol. 1, no. 4, 1976, pp. 875 – 893. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3173239. Accessed 20 March 2022.

—. Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing. Translated by Susan Sellers and Sarah Cornell, Columbia University Press, 1993.

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Columbia University Press, 1982.

Okazaki, Kyôko. Helter Skelter. Vertical, 2013.

Okazaki, Kyôko. River’s Edge. Casterman, 2007.

Yuknavitch, Lidia. The Small Backs of Children. Harper, 2015.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply