You’ve been working on your comic for what probably seems like forever and finally, you feel that you are ready to share it with the world. Of course, you can always go the route of self-publishing, but that carries with it a number of obligations and expectations — printing, shipping, marketing — that you may not have the desire or the knowledge to take on. Thankfully, there are a number of amazing small press comics publishers who are constantly looking to expand their catalog and bring new voices into the world.

Unfortunately, though, as much as there are ethical publishers who want what’s best for the artists they publish, there are also bad actors who prey on the talents of young and new creators.

How do I move forward from an idea to a finished book? How should I approach the licensing of print and digital rights for my comics? Who owns the copyright for my work? How do royalties and advances work? There are a lot of questions about the publishing process, some of which are unique to comics, and some of which are standard areas of concern for working artists around the world.

Part of the goal of Fieldmouse Press, the nonprofit press that publishes SOLRAD, is to advance the comics arts. We see the continued social and economic success of cartoonists as integral to that goal. SOLRAD has devoted and will continue to devote resources to this area of focus.

To this end, we are running an ongoing feature at SOLRAD called KNOWING IS HALF THE BATTLE where we both feature an artist every week and ask for their advice about navigating the world of comics publishing, best practices for the business of comics, and other general advice.

For the initial interview for this series, Sarah Wray from Astra Editorial, who has worked with publishers such as Avery Hill, Liminal 11, and Breakdown Press, reached out to a number of cartoonists that she has worked with and provided them with the following prompting statements:

- The main thing(s) I expect from a comics publisher is/are…

- My #1 advice for submitting to agents and publishers…

- A sneaky red flag or shady thing I would warn new creators to look out for…

- I think it can be worth it to take a lower-paid illustration job in return for ___…

- If a publisher/offer seemed too good to be true, here’s how I’d check it out…

- An organization I’d go to for support if I needed advice or if something went wrong…

- My best tip for promoting your work online and at cons…

- To take care of your health / mental health as an artist, I recommend…

- I wish someone had told me ___ before I started working in the comics industry…

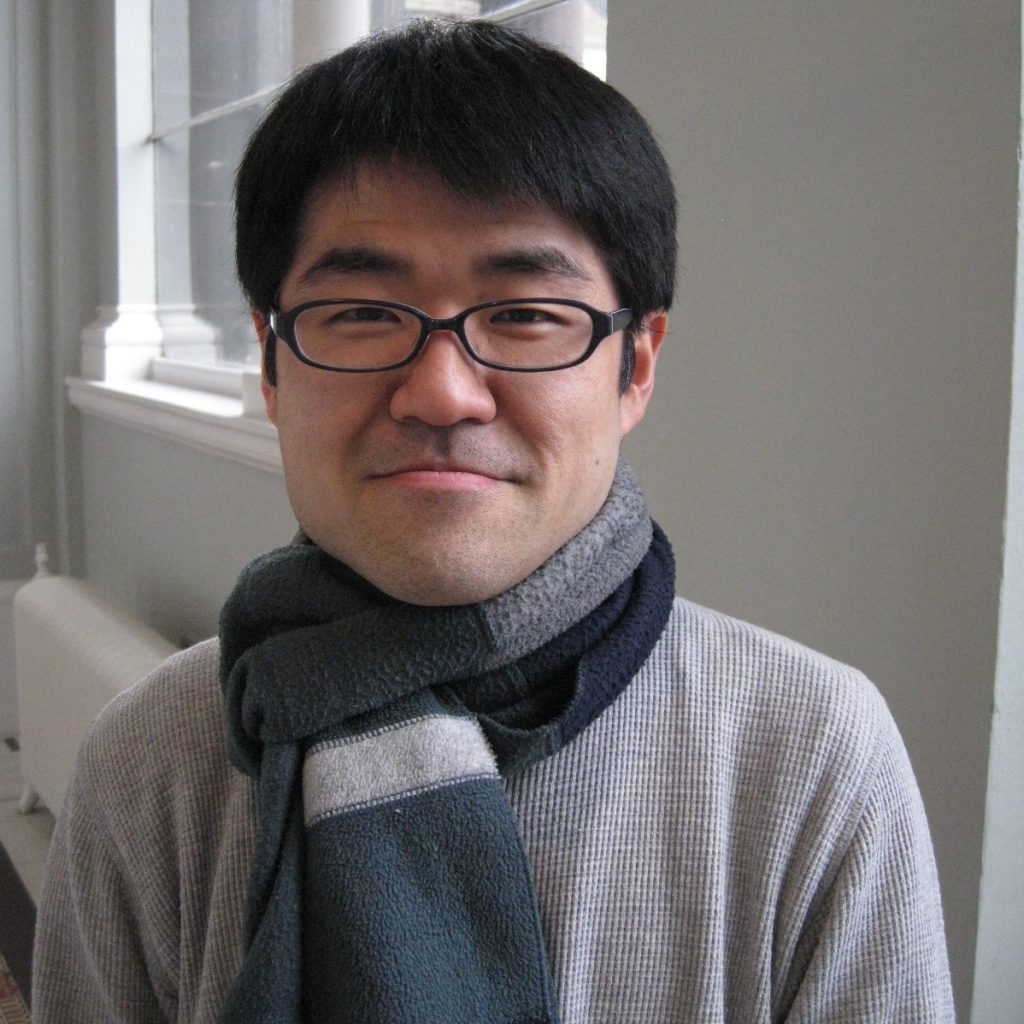

Today on KNOWING IS HALF THE BATTLE we’re featuring tips from Fumio Obata.

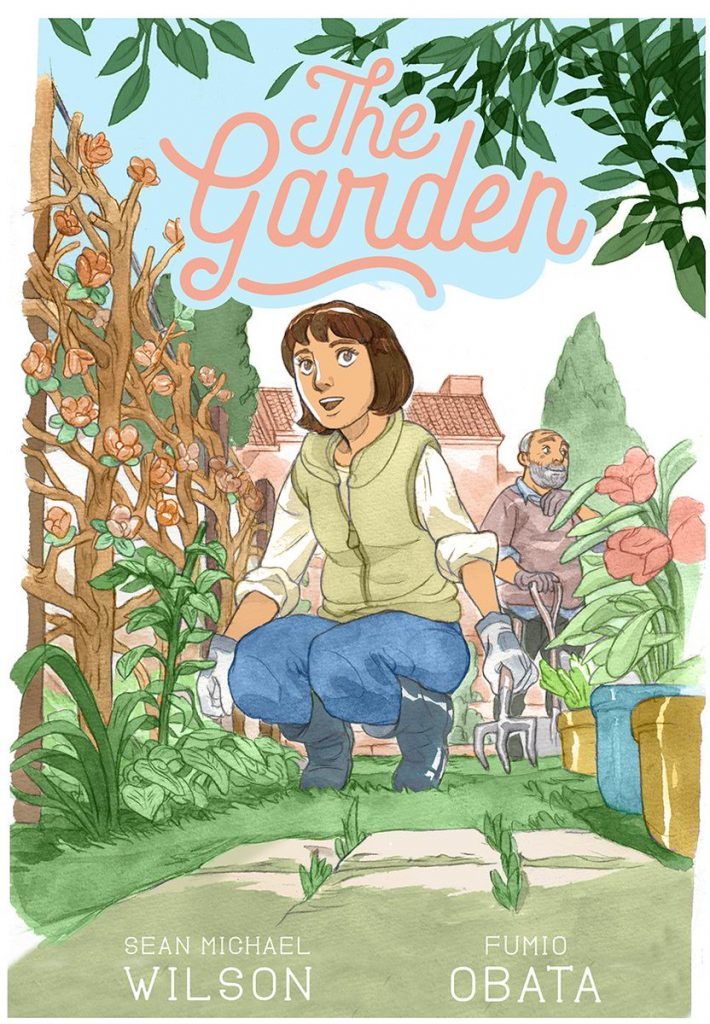

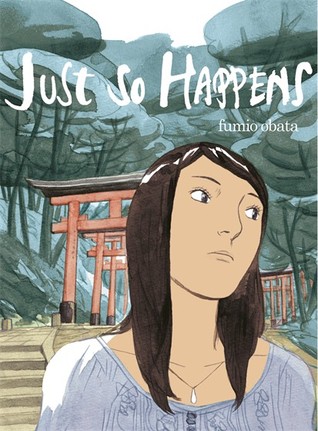

Fumio Obata is a comic book artist and specialist in sequential image design. Fumio is also an illustrator and lecturer in Art and Design. His style and work are influenced by both Japanese and European esthetics. You can find more about him and his work at http://www.fumioobata.co.uk/ and find him on Twitter and Instagram. His latest work is The Garden from Liminal 11.

Sometimes you’ll get asked to send pages to an anthology project that fails. So make sure you investigate those people well by surfing the internet to find out if they have done previous projects professionally. What’s important is that even the project fails, you still get compensation or full pay. So make sure you look for a cancellation clause in your contract.

If you are a starter, alone, and not represented by anyone, then you might be approached by a writer you don’t know. They sometimes say they know a publisher but it’s a bit of a bite. So it is advised to ask for a contract between you and the writer, and if she or he backs away, then that tells the whole story. For making a contract, this is a useful place to refer. https://www.pandadoc.com/memorandum-of-agreement-template/

If you know the writer whom you are working with, then you and her/him must discuss and decide percentage shares of the rights in the contact. It shouldn’t be 50/50 for all the rights, but perhaps 60 to you and 40 to the writer, depending on how established your partner is. But nail this down properly between yourselves before the signing, otherwise it could leave some ill-feelings.

If you’re working with another writer for a book at a publisher, ask what the writer is paid in comparison to you. The same may go to the share of the rights, because they may have agreed on things without your knowledge unless you ask.

Publisher:

When you propose a project to a publisher, it’s better to investigate their reputations on social media as much as you can. Or ask your peers and friends. But have more than two publishers in your mind. Be aware of how many books they do every year as well, because that tells their investment power and how long you have to wait for your book to come out.

If you send a synopsis, cover, and 8-10 pages of art to a publisher, and they say they’ll only take the project when they see a complete version, then, in my opinion, it usually means they are not interested. They might hope something of a cracker may come through with everything there, and then they would say yes, but they aren’t showing much respect to your talent and effort, and the completion of the book may likely come to nothing. When they say “show us the whole thing,” ask them if you could submit it elsewhere and see their response.

Always come to an agreement with the number of illustrations and pages that the publishers ask you to do, and make sure you know how many are in color and how many in B&W. And the sizes too (DP page spread, single page, half-size). Pricing changes depend on all this. They sometimes obscure all types/numbers of illustrations in the same category and average out the pricing, but for you, the amount of effort changes dramatically with just one more extra picture to do. Make a list of it, and ask to put in the agreement that if they want a new picture for it, then they have to pay you extra. That includes a cover illustration. If they don’t like paying for the cover and stuff like that, then ask if you can recycle some of your illustrations inside for it, or vice-versa. Otherwise cut down the numbers of pictures to do.

Contract:

The followings are the areas of contracts that I have overlooked before.

Royalty should be at least 10% for you especially when you are both author and illustrator.

Translation Rights 75%-85%

Option and re-offer Clause

I agreed on for my next graphic novel project to be seen first by the publisher I was signing the contract with. It may not be a good idea as it closes other possible options for you. In my case, I asked to exclude non-English publishers if my next book was aiming for non-English language markets.

Dramatization and Documentary Rights Clause

If it’s comic book, then your book could likely attract film producers. In this case, you may want to keep these rights to yourself so you can choose which producers to work with or you can approach one by yourself. I agreed on 85% to myself and 15% to the publisher for these rights. I still needed an agent to bring it back to me in order to work with the producer of my choice. So if you are interested in adapting it to animation, then negotiate if you can keep it to yourself. Apparently, it is 90% to the illustrator and 10% to the publisher when it is children’s book (I could be wrong).

Reversion Clauses

In the event of breaching the trust by the publisher or if they declare bankruptcy, all of your rights should come back to you. That includes reprints and dramatization. Re-prints are important – if your book goes out of print and the publisher doesn’t plan to reprint, then you can get all the rights back and approach another publisher by yourself.

If you have tips about publishing you would like to share with SOLRAD, please email Daniel Elkin, our editor, at elkin@fieldmouse.press.

Thanks to Sarah Wray for contacting cartoonists and setting up this series of micro-interviews.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply